Viral pneumonia

| Viral pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease, respirology |

Viral pneumonia is a pneumonia caused by a virus. Pneumonia is an infection that causes inflammation in one or both of the lungs. The pulmonary alveoli fill with fluid or pus making it difficult to breathe.[1] Pneumonia can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites.[1] Viruses are the most common cause of pneumonia in children, while in adults bacteria are a more common cause.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of viral pneumonia include fever, non-productive cough, runny nose, and systemic symptoms (e.g. myalgia, headache). Different viruses cause different symptoms.

Cause

Common causes of viral pneumonia are:

- Influenza virus A and B[3]

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)[3]

- Human parainfluenza viruses (in children)[3]

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[4]

Rarer viruses that commonly result in pneumonia include:

- Adenoviruses (in military recruits)[3]

- Metapneumovirus[5]

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)[6]

- Middle East respiratory syndrome virus (MERS-CoV)

- Hantaviruses[7]

Viruses that primarily cause other diseases, but sometimes cause pneumonia include:

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV), mainly in newborns or young children

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV)

- Measles virus

- Rubella virus

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV), mainly in people with immune system problems

- Smallpox virus

- Dengue virus

The most commonly identified agents in children are respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, human bocavirus, and parainfluenza viruses.[5]

Pathophysiology

Viruses must invade cells in order to reproduce. Typically, a virus will reach the lungs by traveling in droplets through the mouth and nose with inhalation. There, the virus invades the cells lining the airways and the alveoli. This invasion often leads to cell death either through direct killing by the virus or by self-destruction through apoptosis.

Further damage to the lungs occurs when the immune system responds to the infection. White blood cells, in particular lymphocytes, are responsible for activating a variety of chemicals (cytokines) which cause leaking of fluid into the alveoli. The combination of cellular destruction and fluid-filled alveoli interrupts the transportation of oxygen into the bloodstream.

In addition to the effects on the lungs, many viruses affect other organs and can lead to illness affecting many different bodily functions. Some viruses also make the body more susceptible to bacterial infection; for this reason, bacterial pneumonia often complicates viral pneumonia.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis, like with any infection, relies on the detection of the infectious cause. With viral pneumonia, samples are taken from the upper and/or lower respiratory tracts.[8] The samples can then be run through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), allowing for amplification of the virus as that allows better detection if present in the sample.[9] Other ways for a diagnosis to be obtained is by ordering a chest x-ray, blood tests, pulse oximetry, and a medical/family history to see if there are any known risks or previous exposures to a person with viral pneumonia.[9] If the person is in serious condition and in the hospital there are more invasive studies that can be run to diagnosis the person.[9]

Prevention

The best prevention against viral pneumonia is vaccination against influenza, chickenpox (varicella zoster), herpes zoster, measles, respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (RSV), rubella, and adenovirus vaccine. [10][11] Besides vaccination there are no other ways to prevent viral pneumonia besides basic hygiene skills like covering the mouth when coughing or sneezing, staying home when sick, and washing your hands frequently.

Treatment

In cases of viral pneumonia where influenza A or B are thought to be causative agents, patients who are seen within 48 hours of symptom onset may benefit from treatment with oseltamivir, or zanamivir, or peramivir. [12] Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has no direct acting treatments, but ribavirin is indicated for severe cases.[12] Ribavirin has also been known to be used as a treatment for Parainfluenza Virus, and Adenovirus.[12] Herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus infections are usually treated with acyclovir, whilst ganciclovir is used to treat cytomegalovirus.[12] There is no known efficacious treatment for pneumonia caused by SARS coronavirus, MERS coronavirus, or hantavirus. Other forms of care are largely supportive like oxygen supplementation, treatment of comorbidities, and controlling other symptoms, fever and cough, with medications.[12]

Epidemiology

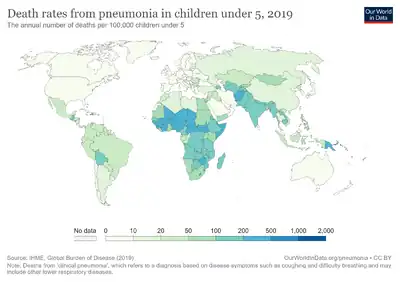

There are roughly 450 million cases of pneumonia every year. Of those case, viral pneumonia counts for about 200 million cases which includes about 100 million children and 100 million adults. [13] Viral pneumonia is more prevalent in the very young, less than 5 years old, and in the very old, more than 75 years old. [13] Developing countries have a higher rate of incidence when it comes to viral pneumonia. On average, developing countries have an incidence rate five times higher than that of developed countries. [13] Being pregnant can also affect the chances of developing viral pneumonia. [14] As with all infectious diseases, viral pneumonia preys on the immunocompromised as well as individuals with one or more comorbidities especially those with:

History

In the pre-antibiotic age, pneumonias had been treated with specific anti-serums of highly variable therapeutic effect and undesirable side-effects (a practice eliminated by the advent of sulfamides in 1936 and the beginning availability of penicillin in the 1940s).

Viral pneumonia was first described by Hobart Reimann in 1938, in an article published by JAMA, An Acute Infection of the Respiratory Tract with Atypical Pneumonia: a disease entity probably caused by a filtrable virus. Reimann, Chairman of the Department of Medicine at Jefferson Medical College, had established the practice of routinely typing the pneumococcal organism in cases where pneumonia presented. Out of this work, the distinction between viral and bacterial strains was noticed.[15]

References

- 1 2 "Pneumonia | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ↑ Ruuskanen, Olli; Lahti, Elina; Jennings, Lance C; Murdoch, David R (2011-04-09). "Viral pneumonia". The Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–1275. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7138033. PMID 21435708.

- 1 2 3 4 Table 13-7 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology: With STUDENT CONSULT Online Access. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. 8th edition.

- ↑ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun; Yu, Ting; Xia, Jiaan; Wei, Yuan; Wu, Wenjuan; Xie, Xuelei; Yin, Wen; Li, Hui; Liu, Min; Xiao, Yan; Gao, Hong; Guo, Li; Xie, Jungang; Wang, Guangfa; Jiang, Rongmeng; Gao, Zhancheng; Jin, Qi; Wang, Jianwei; Cao, Bin (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- 1 2 Ruuskanen, O; Lahti, E; Jennings, LC; Murdoch, DR (2011-04-09). "Viral pneumonia". Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. PMC 7138033. PMID 21435708.

- ↑ "SARS Basics Fact Sheet". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Colby, Thomas V.; Zaki, Sherif R.; Feddersen, Richard M.; Nolte, Kurt B. (October 2000). "Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Is Distinguishable From Acute Interstitial Pneumonia". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 124 (10): 1463–1466. doi:10.5858/2000-124-1463-HPSIDF. PMID 11035576. Archived from the original on 2022-10-18. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Ruuskanen, Olli; Lahti, Elina; Jennings, Lance C; Murdoch, David R (2011-04-09). "Viral pneumonia". The Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–1275. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7138033. PMID 21435708.

- 1 2 3 "Pneumonia | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ↑ Ruuskanen, Olli; Lahti, Elina; Jennings, Lance C; Murdoch, David R (2011-04-09). "Viral pneumonia". The Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–1275. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7138033. PMID 21435708.

- ↑ Freeman, Andrew M.; Leigh, Jr (2020), "Viral Pneumonia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020658, archived from the original on 2020-10-29, retrieved 2020-11-11

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freeman, Andrew M.; Leigh, Jr (2020), "Viral Pneumonia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020658, archived from the original on 2020-10-29, retrieved 2020-11-11

- 1 2 3 Ruuskanen, Olli; Lahti, Elina; Jennings, Lance C; Murdoch, David R (2011-04-09). "Viral pneumonia". The Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–1275. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7138033. PMID 21435708.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Freeman, Andrew M.; Leigh, Jr (2020), "Viral Pneumonia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020658, archived from the original on 2020-10-29, retrieved 2020-11-11

- ↑ John H, Hodges MD (1989). Wagner, MD, Frederick B (ed.). "Thomas Jefferson University: Tradition and Heritage". Jefferson Digital Commons. Part III, Chapter 9: Department of Medicine. p. 253. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |