Rubella virus

| Rubivirus rubellae | |

|---|---|

| |

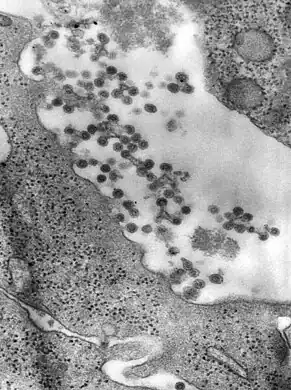

| Transmission electron micrograph of Rubella virus virions | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Hepelivirales |

| Family: | Matonaviridae |

| Genus: | Rubivirus |

| Species: | Rubivirus rubellae |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Rubella virus (RuV) is the pathogenic agent of the disease rubella, transmitted only between humans via the respiratory route, and is the main cause of congenital rubella syndrome when infection occurs during the first weeks of pregnancy.[2][3]

Rubella virus, scientific name Rubivirus rubellae, is a member of the genus Rubivirus and belongs to the family of Matonaviridae, whose members commonly have a genome of single-stranded RNA of positive polarity which is enclosed by an icosahedral capsid.[2][3]

As of 1999 the molecular basis for the causation of congenital rubella syndrome was not yet completely clear, but in vitro studies with cell lines showed that rubella virus has an apoptotic effect on certain cell types. There is evidence for a p53-dependent mechanism.[4]

Morphology

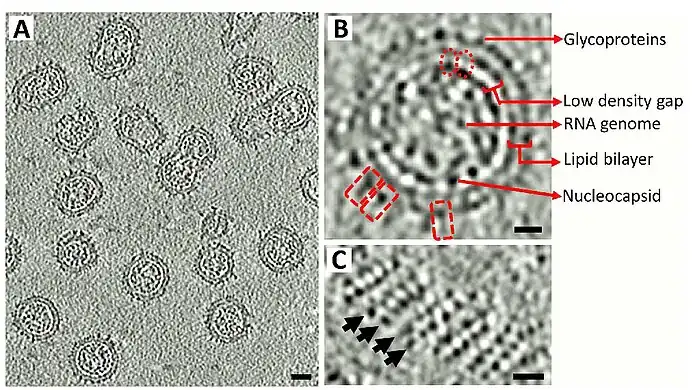

While alphavirus virions are spherical and contain an icosahedral nucleocapsid, RuV virions are pleiomorphic and do not contain icosahedral nucleocapsids.[5]

a-c) Rubella virion morphology

a-c) Rubella virion morphology Negatively-stained transmission electron micrograph reveals the presence of Rubella virus virions

Negatively-stained transmission electron micrograph reveals the presence of Rubella virus virions

Phylogeny

ICTV analyzed the sequence of RuV and compared its phylogeny to that of togaviruses. They concluded:

Phylogenetic analysis of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of alphaviruses, rubella virus and other positive-sense RNA viruses shows the two genera within the Togaviridae are not monophyletic. In particular, rubella virus groups more closely with members of the families Benyviridae, Hepeviridae and Alphatetraviridae, along with several unclassified viruses, than it does with members of the family Togaviridae belonging to the genus Alphavirus.[5]

Taxonomy

Rubella virus (Rubivirus rubellae) is assigned to the Rubivirus genus.[1]

Matonaviridae family

Until 2018, Rubiviruses were classified as part of the family Togaviridae, but have since been changed to be the sole genus of the family Matonaviridae. This family is named after George de Maton, who in 1814 first distinguished rubella from measles and scarlet fever.[5] The change was made by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the central governing body for viral classification. Matonaviridae remains part of the realm that it was already in as Togaviridae, Riboviria, because of its RNA genome and RNA dependent RNA polymerase.[5]

Other rubiviruses

In 2020, Ruhugu virus and Rustrela virus joined Rubella virus as second and third of only three members of the genus Rubivirus.[6] Neither of them are known to infect people.[7]

Structure

The spherical virus particles (virions) of Matonaviridae have a diameter of 50 to 70 nm and are covered by a lipid membrane (viral envelope), derived from the host cell membrane. There are prominent "spikes" (projections) of 6 nm composed of the viral envelope proteins E1 and E2 embedded in the membrane.[8]

The E1 glycoprotein is considered immunodominant in the humoral response induced against the structural proteins and contains both neutralizing and hemagglutinating determinants.[9]

| Genus[10] | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubivirus | Icosahedral | T=4 | Enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Capsid protein

Inside the lipid envelope is a capsid of 40 nm in diameter. The capsid protein (CP) has different functions.[11] Its main tasks are the formation of homooligomeres to form the capsid, and the binding of the genomic RNA. Further is it responsible for the aggregation of RNA in the capsid, it interacts with the membrane proteins E1 and E2 and binds the human host-protein p32 which is important for replication of the virus in the host.[12]

As opposed to alphaviruses the capsid does not undergo autoproteolysis, rather is it cut off from the rest of the polyprotein by the signal-peptidase. Production of the capsid happens at the surface of intracellular membranes simultaneously with the budding of the virus.[13]

Genome

The genome has 9,762 nucleotides and encodes 2 nonstructural polypeptides (p150 and p90) within its 5′-terminal two-thirds and 3 structural polypeptides (C, E2, and E1) within its 3′-terminal one-third. Both envelope proteins E1 and E2 are glycosylated[14][15][16]

There are three sites that are highly conserved in Matonaviruses: a stem-and-loop structure at the 5' end of the genome, a 51-nucleotide conserved sequence near the 5' end of the genome and a 20-nucleotide conserved sequence at the subgenomic RNA start site. Homologous sequences are present in the rubella genome.[15]

The genome encodes several non-coding RNA structures; among them is the rubella virus 3' cis-acting element, which contains multiple stem-loops, one of which has been found to be essential for viral replication.[17]

The only significant region of homology between rubella and the alphaviruses is located at the NH2 terminus of non structural protein 3. This sequence has helicase and replicase activity. [18]

The genome has the highest G+C content of any currently known single stranded RNA virus. Despite this high GC content its codon use is similar to that of its human host.[19][15]

Replication and viral evasion

.jpg.webp)

The viruses attach to the cell surface via specific receptors and are taken up by an endosome being formed. At the neutral pH outside of the cell the E2 envelope protein covers the E1 protein. The dropping pH inside the endosome frees the outer domain of E1 and causes the fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal membrane. Thus, the capsid reaches the cytosol, decays and releases the genome[21][16][22]

The (+)ssRNA (positive, single-stranded RNA) at first only acts as a template for the translation of the non-structural proteins, which are synthesized as a large polyprotein and are then cut into single proteins. The sequences for the structural proteins are first replicated by the viral RNA polymerase (Replicase) via a complementary (-)ssRNA as a template and translated as a separate short mRNA. This short subgenomic RNA is additionally packed in a virion.[23]

Translation of the structural proteins produces a large polypeptide (110 Dalton). This is then endoproteolytically cut into E1, E2 and the capsid protein. E1 and E2 are type I transmembrane proteins which are transported into the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) with the help of an N-terminal signal sequence.[24]

From the ER the heterodimeric E1·E2-complex reaches the Golgi apparatus, where the budding of new virions occurs (unlike alpha viruses, where budding occurs at the plasma membrane. The capsid proteins on the other hand stay in the cytoplasm and interact with the genomic RNA, together forming the capsid.[24]

| Genus[10] | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubivirus | Humans | None | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Secretion | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Aerosol |

Transmission

In terms of the spread of the virus we find that RuV is transmitted via respiration between humans.[5] Additionally a woman who is infected with with the virus while pregnant, can pass it to the baby. 25% to 50% of individuals infected with rubella do not have any symptoms, but they continue to spread the virus to other individuals [25][26]

Rubella (German measles)

.jpg.webp)

Signs and symptoms

The primary symptom of rubella virus infection is the appearance of a rash (exanthem) on the face which spreads to the trunk and limbs and usually fades after three days . The facial rash usually clears as it spreads to other parts of the body. Other symptoms include low grade fever, swollen glands (sub-occipital and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy), joint pains, headache, and conjunctivitis.[27]

Diagnosis

Rubella virus specific IgM antibodies are present in individuals recently infected by rubella virus, but these antibodies can persist for over a year, and a positive test result needs to be interpreted with caution.[28] The presence of these antibodies along with the characteristic rash confirms the diagnosis.[29]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for rubella; however, management is a matter of responding to symptoms to diminish discomfort. Treatment of newborn babies is focused on management of the complications. Congenital heart defects and cataracts can be corrected by direct surgery.[30][2]

Epidemiology

.png.webp)

On the basis of differences in the sequence of the E1 protein, two genotypes have been described which differ by 8 - 10%. These have been subdivided into 13 recognised genotypes - 1a, 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F, 1G, 1h, 1i, 1j, 2A, 2B and 2C.

For typing, the WHO recommends a minimum window that includes nucleotides 8731 to 9469:[31]

- Genotypes 1a, 1E, 1F, 2A and 2B have been isolated in China.

- Genotype 1j has only been isolated from Japan and the Philippines.

- Genotype 1E is found in Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe.

- Genotype 1G has been isolated in Belarus, Cote d'Ivoire and Uganda.

- Genotype 1C is endemic only in Central and South America.

- Genotype 2B has been isolated in South Africa.

- Genotype 2C has been isolated in Russia.

References

- 1 2 Bennett AJ, Paskey AC, Ebinger A, Kuhn JH, Bishop-Lilly KA, Beer M, Goldberg TL (31 July 2020). "Create two new species and rename one species in genus Rubivirus (Hepelivirales: Matonaviridae)" (docx). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Rubella (German measles): Overview". InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 5 November 2020. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- 1 2 Parkman, Paul D. (1996). "Togaviruses: Rubella Virus". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ↑ Megyeri K, Berencsi K, Halazonetis TD, et al. (June 1999). "Involvement of a p53-dependent pathway in rubella virus-induced apoptosis". Virology. 259 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1006/viro.1999.9757. PMID 10364491.

- 1 2 3 4 5 ICTV. "Create a new family Matonaviridae to include the genus Rubivirus, removed from the family Togaviridae Release". Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ↑ Bennett, Andrew J.; Paskey, Adrian C.; Ebinger, Arnt; Pfaff, Florian; Priemer, Grit; Höper, Dirk; Breithaupt, Angele; Heuser, Elisa; Ulrich, Rainer G.; Kuhn, Jens H.; Bishop-Lilly, Kimberly A. (7 October 2020). "Relatives of rubella virus in diverse mammals". Nature. 586 (7829): 424–428. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..424B. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2812-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7572621. PMID 33029010.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (7 October 2020). "Newly discovered viruses suggest 'German measles' jumped from animals to humans". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abf1520. S2CID 225112037. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ↑ Bardeletti G, Kessler N, Aymard-Henry M (1975). "Morphology, biochemical analysis and neuraminidase activity of rubella virus". Arch. Virol. 49 (2–3): 175–86. doi:10.1007/BF01317536. PMID 1212096. S2CID 20699178.

- ↑ Yang, Decheng; Hwang, Dorothy; Qiu, Zhiyong; Gillam, Shirley (November 1998). "Effects of Mutations in the Rubella Virus E1 Glycoprotein on E1-E2 Interaction and Membrane Fusion Activity". Journal of Virology. 72 (11): 8747–8755. doi:10.1128/JVI.72.11.8747-8755.1998. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 110290. PMID 9765418.

- 1 2 "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Chen MH, Icenogle JP (April 2004). "Rubella virus capsid protein modulates viral genome replication and virus infectivity". Journal of Virology. 78 (8): 4314–22. doi:10.1128/jvi.78.8.4314-4322.2004. PMC 374250. PMID 15047844.

- ↑ Beatch MD, Everitt JC, Law LJ, Hobman TC (August 2005). "Interactions between rubella virus capsid and host protein p32 are important for virus replication". J. Virol. 79 (16): 10807–20. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.16.10807-10820.2005. PMC 1182682. PMID 16051872.

- ↑ Beatch MD, Hobman TC (June 2000). "Rubella virus capsid associates with host cell protein p32 and localizes to mitochondria". J. Virol. 74 (12): 5569–76. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.12.5569-5576.2000. PMC 112044. PMID 10823864.

- ↑ Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin J.; Mandell, Gerald L. (19 October 2009). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2127. ISBN 978-1-4377-2060-0. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 Dominguez G, Wang CY, Frey TK (July 1990). "Sequence of the genome RNA of rubella virus: evidence for genetic rearrangement during togavirus evolution". Virology. 177 (1): 225–38. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(90)90476-8. PMC 7131718. PMID 2353453.

- 1 2 Chen, Min-Hsin; Icenogle, Joseph (1 January 2006). "Chapter 1 Molecular Virology of Rubella Virus". Perspectives in Medical Virology. Elsevier. pp. 1–18. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ↑ Chen, MH; Frey TK (1999). "Mutagenic analysis of the 3' cis-acting elements of the rubella virus genome". J Virol. 73 (4): 3386–3403. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.4.3386-3403.1999. PMC 104103. PMID 10074193.

- ↑ Götte, Benjamin; Liu, Lifeng; McInerney, Gerald M. (March 2018). "The Enigmatic Alphavirus Non-Structural Protein 3 (nsP3) Revealing Its Secrets at Last". Viruses. 10 (3): 105. doi:10.3390/v10030105. ISSN 1999-4915. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ Zhou Y, Chen X, Ushijima H, Frey TK (2012) Analysis of base and codon usage by rubella virus. Arch Virol

- ↑ Amurri, Lucia; Reynard, Olivier; Gerlier, Denis; Horvat, Branka; Iampietro, Mathieu (26 November 2022). "Measles Virus-Induced Host Immunity and Mechanisms of Viral Evasion". Viruses. 14 (12): 2641. doi:10.3390/v14122641. ISSN 1999-4915. MeV interactions with the innate immune system ...viral ability to inhibit the induction of the interferon cascade

- ↑ Das, Pratyush Kumar; Kielian, Margaret (26 April 2021). "Molecular and Structural Insights into the Life Cycle of Rubella Virus". Journal of Virology. 95 (10): e02349–20. doi:10.1128/JVI.02349-20. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 8139664. PMID 33627388.

- ↑ Lee, Jia-Yee; Bowden, D. Scott (October 2000). "Rubella Virus Replication and Links to Teratogenicity". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (4): 571–587. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.4.571. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 88950. PMID 11023958.

- ↑ "Togaviridae- Classification and Taxonomy". Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- 1 2 Garbutt M, Law LM, Chan H, Hobman TC (May 1999). "Role of rubella virus glycoprotein domains in assembly of virus-like particles". J. Virol. 73 (5): 3524–33. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.5.3524-3533.1999. PMC 104124. PMID 10196241.

- ↑ "Rubella - PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization". www.paho.org. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ↑ "Rubella". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ↑ Edlich RF, Winters KL, Long WB, Gubler KD (2005). "Rubella and congenital rubella (German measles)". J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 15 (3): 319–28. doi:10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v15.i3.80. PMID 16022642.

- ↑ Best JM (2007). "Rubella". Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 12 (3): 182–92. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.017. PMID 17337363.

- ↑ Stegmann BJ, Carey JC (2002). "TORCH Infections. Toxoplasmosis, Other (syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes infections". Curr Women's Health Rep. 2 (4): 253–8. PMID 12150751.

- ↑ Khandekar R, Sudhan A, Jain BK, Shrivastav K, Sachan R (2007). "Pediatric cataract and surgery outcomes in Central India: a hospital based study". Indian J Med Sci. 61 (1): 15–22. doi:10.4103/0019-5359.29593. PMID 17197734. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ↑ "Standardization of the nomenclature for genetic characteristics of wild-type rubella viruses" (PDF). Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 80 (14): 126–132. 2005. PMID 15850226. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2009.

Further reading

- David M. Knipe, Peter M. Howley et al. (eds.): Fields Virology 4. Auflage, Philadelphia 2001

- C.M. Fauquet, M.A. Mayo et al.: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, London San Diego 2005

External links

- Viralzone: Rubivirus Archived 20 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine