Cowpox

| Cowpox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cowpox lesions on forearm on day 7 after onset of illness.[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases[2] |

| Symptoms | Fluid filled bumps on the hands, fever, lymphadenopathy[2] |

| Causes | Cowpox virus[2] |

Cowpox is an infection caused by the cowpox virus (CPXV).[3] It presents with large fluid filled bumps in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, typically following contact with an infected cow.[2] The hands and face are most frequently affected and the spots are generally very painful.[4]

The virus, part of the genus Orthopoxvirus, is zoonotic and closely related to the vaccinia virus.[5] Cowpox is more commonly found in animals other than bovines, such as rodents.[5] Cowpox is similar to, but much milder than, the highly contagious and often deadly smallpox disease.[5]

The first description of cowpox was given by Jenner in 1798.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The rash typically begins as a flat mark before becoming a small bump, which fills with clear fluid and then yellow fluid, before becoming a dark hard crust.[4] It tends to be painful and becomes red and swollen.[4] It is typically accompanied by fever, swollen glands and fatigue, and may take 3-months to recover.[4]

Medical use

Naturally occurring cases of cowpox were not common, but it was discovered that the vaccine could be “carried” in humans and reproduced and disseminated human-to-human. Jenner's original vaccination used lymph from the cowpox pustule on a milkmaid, and subsequent “arm-to-arm” vaccinations applied the same principle. As this transfer of human fluids came with its own set of complications, a safer manner of producing the vaccine was first introduced in Italy. The new method used cows to manufacture the vaccine using a process called “retrovaccination", in which a heifer was inoculated with humanized cowpox virus, and it was passed from calf to calf to produce massive quantities efficiently and safely. This then led to the next incarnation, “true animal vaccine”, which used the same process but began with naturally-occurring cowpox virus, and not the humanized form.

This method of production proved to be lucrative and was taken advantage of by many entrepreneurs needing only calves and seed lymph from an infected cow to manufacture crude versions of the vaccine. W. F. Elgin of the National Vaccine Establishment presented his slightly refined technique to the Conference of State and Provincial Boards of Health of North America. A tuberculosis-free calf, stomach shaved, would be bound to an operating table, where incisions would be made on its lower body. Glycerinated lymph from a previously inoculated calf was spread along the cuts. After a few days, the cuts would have scabbed or crusted over. The crust was softened with sterilized water and mixed with glycerin, which disinfected it, then stored hermetically-sealed in capillary tubes for later use.

At some point, the virus in use was no longer cowpox, but vaccinia. Scientists have not determined exactly when the change or mutation occurred, but the effects of vaccinia and cowpox virus as vaccine are nearly the same.[7]

The virus is found in Europe, and mainly in the UK. Human cases today are very rare and most often contracted from domestic cats. The virus is not commonly found in cattle; the reservoir hosts for the virus are woodland rodents, particularly voles. From these rodents, domestic cats contract and transmit the virus to humans.[8] Symptoms in cats include lesions on the face, neck, forelimbs, and paws, and less commonly upper respiratory tract infections.[9] Symptoms of infection with cowpox virus in humans are localized, pustular lesions generally found on the hands and limited to the site of introduction. The incubation period is 9 to 10 days. The virus is prevalent in late summer and autumn.

Once vaccinated, a patient develops antibodies that make them immune to cowpox, but they also develop immunity to the smallpox virus, or Variola virus. The cowpox vaccinations and later incarnations proved so successful that in 1980, the World Health Organization announced that smallpox was the first disease to be eradicated by vaccination efforts worldwide.[10] Other orthopox viruses remain prevalent in certain communities and continue to infect humans, such as the cowpox virus in Europe, vaccinia in Brazil, and monkeypox virus in Central and West Africa.

Cause

| Cowpox virus | |

|---|---|

| |

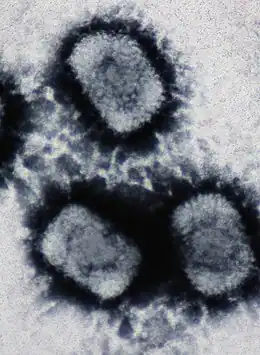

| Electron micrograph of three Cowpox virus particles | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Pokkesviricetes |

| Order: | Chitovirales |

| Family: | Poxviridae |

| Genus: | Orthopoxvirus |

| Species: | Cowpox virus |

Cowpox is due to infection by the cowpox virus (CPXV).

Prevention

Today, the virus is found in Europe, mainly in the UK. Human cases are very rare (though in 2010 a laboratory worker contracted cowpox[11]) and most often contracted from domestic cats. Human infections usually remain localized and self-limiting, but can become fatal in immunosuppressed patients. The virus is not commonly found in cattle; the reservoir hosts for the virus are woodland rodents, particularly voles.[12] Domestic cats contract the virus from these rodents. Symptoms in cats include lesions on the face, neck, forelimbs, and paws, and, less commonly, upper respiratory tract infections. Symptoms of infection with cowpox virus in humans are localized, pustular lesions generally found on the hands and limited to the site of introduction. The incubation period is nine to ten days. The virus is most prevalent in late summer and autumn.

Immunity to cowpox is gained when the smallpox vaccine is administered. Although the vaccine now uses vaccinia virus, the poxviruses are similar enough that the body becomes immune to both cow- and smallpox.

History

The transferral of the disease was first observed in dairymaids who touched the udders of infected cows and consequently developed the signature pustules on their hands.[5] Its close resemblance to the mild form of smallpox and the observation that dairy farmers[13] were immune to smallpox inspired the modern smallpox vaccine, created and administered by English physician Edward Jenner.[14] The word "vaccination", coined by Jenner in 1796,[14] is derived from the Latin adjective vaccinus, meaning "of or from the cow".[10]

After inoculation, vaccination using the cowpox virus became the primary defense against smallpox. After infection by the cowpox virus, the body (usually) gains the ability to recognize the similar smallpox virus from its antigens and is able to fight the smallpox disease much more efficiently.

The cowpox virus contains 186 thousand base pairs of DNA, which contains the information for about 187 genes. This makes cowpox one of the most complicated viruses known. Some 100 of these genes give instructions for key parts of the human immune system, giving a clue as to why the closely related smallpox is so lethal.[15] The vaccinia virus now used for smallpox vaccination is sufficiently different from the cowpox virus found in the wild as to be considered a separate virus.[16]

Discovery

.png.webp)

In the years from 1770 to 1790, at least six people who had contact with a cow had independently tested the possibility of using the cowpox vaccine as an immunization for smallpox in humans. Among them were the English farmer Benjamin Jesty, in Dorset in 1774 and the German teacher Peter Plett in 1791.[17] Jesty inoculated his wife and two young sons with cowpox, in a successful effort to immunize them to smallpox, an epidemic of which had arisen in their town. His patients who had contracted and recovered from the similar but milder cowpox (mainly milkmaids), seemed to be immune not only to further cases of cowpox, but also to smallpox. By scratching the fluid from cowpox lesions into the skin of healthy individuals, he was able to immunize those people against smallpox.[18]

Reportedly, farmers and people working regularly with cattle and horses were often spared during smallpox outbreaks. Investigations by the British Army in 1790 showed that horse-mounted troops were less infected by smallpox than infantry, due to probable exposure to the similar horsepox virus (Variola equina). By the early 19th century, more than 100,000 people in Great Britain had been vaccinated. The arm-to-arm method of transfer of the cowpox vaccine was also used to distribute Jenner's vaccine throughout the Spanish Empire. Spanish king Charles IV's daughter had been stricken with smallpox in 1798, and after she recovered, he arranged for the rest of his family to be vaccinated.[19]

In 1803, the king, convinced of the benefits of the vaccine, ordered his personal physician Francis Xavier de Balmis, to deliver it to the Spanish dominions in North and South America. To maintain the vaccine in an available state during the voyage, the physician recruited 22 young boys who had never had cowpox or smallpox before, aged three to nine years, from the orphanages of Spain. During the trip across the Atlantic, de Balmis vaccinated the orphans in a living chain. Two children were vaccinated immediately before departure, and when cowpox pustules had appeared on their arms, material from these lesions was used to vaccinate two more children.[20]

In 1796, English medical practitioner Edward Jenner tested the theory that cowpox could protect someone from being infected by smallpox. There had long been speculation regarding the origins of Jenner's variolae vaccinae, until DNA sequencing data showed close similarities between horsepox and cowpox viruses. Jenner noted that farriers sometimes milked cows and that material from the equine disease could produce a vesicular disease in cows from which variolae vaccinae was derived. Contemporary accounts provide support for Jenner's speculation that the vaccine probably originated as an equine disease called "grease".[21] Although cowpox originates on the udder of cows, Jenner took his sample from a milkmaid, Sarah Nelmes.

Jenner extracted the pus of one of the lesions formed by cowpox on Nelmes to James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy who had never had smallpox. He eventually developed a scab and fever that was manageable. Approximately six weeks later, Jenner then introduced an active sample of the smallpox virus into Phipps to test the theory. After being observed for an extended amount of time, it was recorded that Phipps did not receive a reaction from it. Although Jenner was not the first person to conceive the notion of cowpox protecting against the smallpox virus, his experiment proved the theory. It was later discovered that the cowpox vaccination only worked temporarily against the invasion of smallpox and the procedure would need to be repeated several times through one's lifetime to remain smallpox free.

In later years, Jenner popularized the experiment, calling it a vaccination from the Latin for cow, vacca. The amount of vaccinations among people of that era increased drastically. It was widely considered to be a relatively safer procedure compared to the mainstream inoculation. Although Jenner was propelled into the spotlight from the vaccination popularity, he mainly focused on science behind why the cowpox allowed persons to not be infected by smallpox. The honour of the discovery of the vaccination is often attributed to Benjamin Jesty, but he was no scientist and did not repeat or publish his findings. He is considered to be the first to use cowpox as a vaccination, though the term vaccination was not invented yet.

During the midst of the smallpox outbreak, Jesty transferred pieces of cow udder which he knew had been infected with cowpox into the skin of his family members in the hopes of protecting them. Jesty did not publicize his findings, and Jenner, who performed his first inoculation 22 years later and publicized his findings, assumed credit. It is said that Jenner made this discovery by himself, possibly without knowing previous accounts 20 years earlier. Although Jesty may have been the first to discover it, Jenner made vaccination widely accessible and has therefore been credited for its invention.[22]

Opposition

The majority of the population at the time accepted the up-and-coming vaccination. However, there was still opposition from individuals who were reluctant to change from the inoculations. In addition, there became a growing concern from parties who were worried about the unknown repercussions of infecting a human with an animal disease. One way individuals expressed their discontent was to draw comics that sometimes depicted small cows growing from the sites of vaccination. Others publicly advocated for the continuance of the inoculations; however, this was not because of their discontent for the vaccinations. Some of their reluctance had to do with an apprehensiveness for change. They had become so familiar with the process, outcome, positives, and negatives of inoculations that they did not want to be surprised by the outcome or effects of the vaccinations. Jenner soon eased their minds after extensive trials. However, others advocated against vaccinations for different reason. Because of the high price of inoculation, Jenner experienced very few common folk who were not willing to accept the vaccination. Due to this, Jenner found many subjects for his tests. He was able to publish his results in a pamphlet in 1798: An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease, Discovered in some of the Western Counties of England particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the Name of Cow Pox.[23] [24]

British Parliament

While the vaccination's popularity increased exponentially, so did its monetary value. This was realized by the British Parliament, which compensated Jenner 10,000 pounds for the vaccination. In addition, they later compensated Jenner an additional 20,000 pounds. In the coming years, Jenner continued advocacy for his vaccination over the still popular inoculation. Eventually, in 1840, the inoculation became banned in England and was replaced with the cowpox vaccination as the main medical solution to combat smallpox. The cowpox vaccination saved the British Army thousands of soldiers, by making them immune to the effects of smallpox in upcoming wars. The cowpox also saved the United Kingdom thousands of pounds.[25]

Kinepox

Kinepox is an alternative term for the smallpox vaccine used in early 19th-century America. Popularized by Jenner in the late 1790s, kinepox was a far safer method for inoculating people against smallpox than the previous method, variolation, which had a 3% fatality rate.

In a famous letter to Meriwether Lewis in 1803, Thomas Jefferson instructed the Lewis and Clark expedition to "carry with you some matter of the kine-pox; inform those of them with whom you may be, of its efficacy as a preservative from the smallpox; & encourage them in the use of it..."[26] Jefferson had developed an interest in protecting American Indians from smallpox, having been aware of epidemics along the Missouri River during the previous century. A year before his special instructions to Lewis, Jefferson had persuaded a visiting delegation of North American Indian chieftains to be vaccinated with kinepox during the winter of 1801–1802. Unfortunately, Lewis never got the opportunity to use kinepox during the pair's expedition, as it had become inadvertently inactive—a common occurrence in a time before vaccines were stabilized with preservatives such as glycerol or kept at refrigeration temperatures.

References

- ↑ Pelkonen PM, Tarvainen K, Hynninen A, Kallio ER, Henttonen K, Palva A, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O (November 2003). "Cowpox with severe generalized eruption, Finland". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (11): 1458–61. doi:10.3201/eid0911.020814. PMC 3035531. PMID 14718092.

- 1 2 3 4 Barlow, Gavin; Irving, William L.; Moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 517. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ↑ Carroll, DS; Emerson, GL; Li, Y; Sammons, S; Olson, V; Frace, M; Nakazawa, Y; Czerny, CP; Tryland, M; Kolodziejek, J; Nowotny, N; Olsen-Rasmussen, M; Khristova, M; Govil, D; Karem, K; Damon, IK; Meyer, H (2011). "Chasing Jenner's vaccine: revisiting cowpox virus classification". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23086. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623086C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023086. PMC 3152555. PMID 21858000.

- 1 2 3 4 Petersen, Brett W.; Damon, Inger K. (2020). "348. Smallpox, monkeypox and other poxvirus infections". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 2180–2183. ISBN 978-0-323-53266-2. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Vanessa Ngan, "Viral and Skin Infections" Archived 2016-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2009

- ↑ "Cowpox and paravaccinia". British medical journal. 4 (5575): 308–9. 11 November 1967. PMID 4293285. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ Willrich M (2011). Pox. New York: Penguin Books.

- ↑ Chomel BB (July 2014). "Emerging and Re-Emerging Zoonoses of Dogs and Cats". Animals. 4 (3): 434–45. doi:10.3390/ani4030434. PMC 4494318. PMID 26480316.

- ↑ Mansell JK, Rees CA (2005). "Cutaneous manifestations of viral disease". In August, John R. (ed.). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0423-7.

- 1 2 Abbas, Abul K. (2003). Cellular and Molecular Immunology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0008-6.

- ↑ "Cowpox infection in US lab worker called a first". Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ↑ Kurth A, Wibbelt G, Gerber HP, Petschaelis A, Pauli G, Nitsche A (April 2008). "Rat-to-elephant-to-human transmission of cowpox virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (4): 670–71. doi:10.3201/eid1404.070817. PMC 2570944. PMID 18394293.

- ↑ "What's The Real Story About The Milkmaid And The Smallpox Vaccine?". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- 1 2 Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina: "Edward Jenner and the Discovery of Vaccination" Archived 2011-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, exhibition, 1996

- ↑ Moore P (2001). Killer Germs: Rogue Diseases of the Twenty-First Century. London: Carlton. ISBN 978-1-84222-150-1.

- ↑ Yuan, Jenifer The Small Pox Story Archived 2013-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Plett PC (2006). "[Peter Plett and other discoverers of cowpox vaccination before Edward Jenner]". Sudhoffs Archiv (in Deutsch). 90 (2): 219–32. PMID 17338405.

- ↑ Williams, Nigel (2007-03-06). "Pox precursors". Current Biology. 17 (5): R150–R151. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.024. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 17387780. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ↑ Patowary, Kaushik (2020-12-09). "Balmis Expedition - How Orphans Took The Smallpox Vaccine Around The World". Amusing Planet. Archived from the original on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2021-08-11.

- ↑ Tucker JB (2001). Scourge: The Once and Future Threat of Smallpox. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-87113-830-9.

- ↑ Noyce RS, Lederman S, Evans DH (2018-01-19). Thiel V (ed.). "Construction of an infectious horsepox virus vaccine from chemically synthesized DNA fragments". PLOS ONE. 13 (1): e0188453. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1388453N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188453. PMC 5774680. PMID 29351298.

- ↑ Science and the practice of medicine in the nineteenth century. Cambridge.

- ↑ Lindemann M. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe.

- ↑ Jenner, Edward. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae: a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the cow pox. Archived from the original on 2021-10-06. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ↑ Riedel S (January 2005). "Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination". Proceedings. 18 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. PMC 1200696. PMID 16200144.

- ↑ "Jefferson's Instructions to Lewis and Clark (1803)". Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

General sources

- Peck, David R. (2002). Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Farcountry Press. ISBN 978-1-56037-226-4.

| Classification |

|---|