Congenital rubella syndrome

| Congenital rubella syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Congenital rubella infection (CRI) | |

_PHIL_4284_lores.jpg.webp) | |

| White pupils due to congenital cataracts in a child with congenital rubella syndrome | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Hearing, heart, and eye problems[1] |

| Complications | Miscarriage, stillbirth, autism[1][2] |

| Duration | Life-long[2] |

| Causes | Rubella infection in early pregnancy[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Supported by blood, urine, or nose swab testing[4][2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Congenital CMV infection, congenital syphilis, congenital varicella[5] |

| Prevention | Rubella vaccination[4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[2] |

| Frequency | 100,000/yr[6] |

Congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) is when rubella during pregnancy results in birth defects in the baby.[1] Classic symptoms include hearing, heart, and eye problems such as cataracts and glaucoma.[1] Other features may include large spleen, small head, and developmental delay.[1] A few have a characteristic rash.[7] Complications may include miscarriage, stillbirth, autism, and encephalopathy.[1][2][5]

The risk is greatest if infection of the mother occurs in early pregnancy, before 12 weeks of gestation.[1][3] If infection occurs after 18 weeks, problems generally do not occur.[1] Up to half of infected pregnant women have no symptoms, though are still contagious.[8] Diagnosis may include testing the blood, urine, or a nose swab.[2][4]

Prevention is by rubella vaccination of the population.[4] Pregnant women may be tested to verify that they are immune.[2] Those who are infected during pregnancy may be offered the option of an abortion.[2] Tentative evidence supports giving immune globulin (IG) against rubella to an infected pregnant mother.[2] Care of children is supportive.[2] They should be tested for viral shedding monthly, until two negatives occur, as this may continue for a year or more.[4]

Congenital rubella syndrome affects about 100,000 babies a year.[6] It is most common in Africa and South-East Asia and is exceedingly rare in the Americas.[4][9] In the United States less than a case a year has occurred on average since 2005.[3] Before the introduction of vaccines against the disease up to 0.4% of babies were affected.[9] It was first described in 1941 by Australian Norman McAlister Gregg.[8] A vaccine was developed following the 1962-1965 rubella epidemic.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Classic symptoms of congenital rubella syndrome include most frequently eye abnormalities—especially retinopathy, cataract, glaucoma, and microphthalmia.[11] Other common symptoms include ear problems such as sensorineural deafness, and heart problems such as pulmonary artery stenosis and patent ductus arteriosus.[11]

Other symptoms may include:

- Spleen, liver, or bone marrow problems (some of which may disappear shortly after birth)

- Intellectual disability[11]

- Small head size (microcephaly)

- Low birth weight[12]

- Thrombocytopenic purpura[11]

- Extramedullary hematopoiesis (presents as a characteristic blueberry muffin rash)[11]

- Enlarged liver

- Small jaw size

- Skin lesions [12]

Children who have been exposed to rubella in the womb should also be watched closely as they age for any indication of:

- Developmental delay[11]

- Autism[13]

- Schizophrenia[14]

- Growth retardation[15]

- Learning disabilities

- Diabetes mellitus[16]

Purple macules

Purple macules Infant with skin lesions from congenital rubella (blueberry muffin lesions)

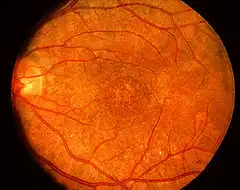

Infant with skin lesions from congenital rubella (blueberry muffin lesions) "Salt-and-pepper" retinopathy is characteristic of congenital rubella.[17]

"Salt-and-pepper" retinopathy is characteristic of congenital rubella.[17]

Cause

The cause of congenital rubella syndrome is the rubella virus infecting the placenta and baby.[5]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of this condition is done via molecular analysis done on amniotic fluid and by positive Rubella specific IgM after birth.[5]

Differential diagnosis

The following conditions may appear similar:[5]

- Enteroviruses

- CMV

- Herpes simplex virus

- Varicella

- Syphilis

- Toxoplasma gondii

Prevention

Vaccinating the majority of the population is effective at preventing congenital rubella syndrome.[18] For women who plan to become pregnant, the MMR (measles mumps, rubella) vaccination is highly recommended, at least 28 days prior to conception.[12] The vaccine should not be given to women who are already pregnant as it contains live viral particles.[12]

Other preventative actions can include the screening and vaccinations of high-risk personnel, such as medical and child care professions.[19]

Management

There is no specific treatment.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Congenital Infectious Syndromes: Congenital Rubella Syndrome". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 April 2021. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shukla, Samarth; Maraqa, Nizar F. (2023). "Congenital Rubella". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Congenital Rubella Syndrome - Vaccine Preventable Diseases Surveillance Manual | CDC". www.cdc.gov. CDC. 22 August 2023. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Atkinson, William (2011). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12th ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 301–323. ISBN 9780983263135. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orphanet. "Orphanet: Congenital rubella syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- 1 2 "Rubella Information For Healthcare Professionals | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 12 April 2023. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ↑ Rochester, Caitlin K.; Adams, Daniel J. (2022). "12. Rubella". In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.). Netter's Infectious Diseases (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-323-71159-3. Archived from the original on 2023-09-10. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- 1 2 Vesikari, Timo; Usonis, Vytautas (2021). "9. Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 2023-10-05. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- 1 2 "Rubella". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ↑ Howson, Christopher P.; Howe, Cynthia J.; Fineberg, Harvey V. (1991). "2. Histories of Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines". Adverse Effects of Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines: A Report of the Committee to Review the Adverse Consequences of Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines. National Academies Press (US). pp. 9–31. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reef, Susan E. (2020). "344. Rubella (German measles)". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 2170–2171. ISBN 978-0-323-53266-2. Archived from the original on 2023-09-10. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- 1 2 3 4 "Congenital Rubella Symptoms & Causes | Boston Children's Hospital". www.childrenshospital.org. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ↑ Muhle, R; Trentacoste, SV; Rapin, I (May 2004). "The genetics of autism". Pediatrics. 113 (5): e472–86. doi:10.1542/peds.113.5.e472. PMID 15121991. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ↑ Brown, A. S (9 February 2006). "Prenatal Infection as a Risk Factor for Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 32 (2): 200–202. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj052. PMC 2632220. PMID 16469941.

- ↑ Naeye, Richard L. (1965-12-20). "Pathogenesis of congenital rubella". JAMA. 194 (12): 1277–1283. doi:10.1001/jama.1965.03090250011002. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 5898080.

- ↑ Forrest, Jill M.; Menser, Margaret A.; Burgess, J. A. (1971-08-14). "High Frequency of Diabetes Mellitus in Young Adults with Congenital Rubella". The Lancet. 298 (7720): 332–334. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)90057-2. PMID 4105044.

- ↑ Sudharshan S, Ganesh SK, Biswas J (2010). "Current approach in the diagnosis and management of posterior uveitis". Indian J Ophthalmol. 58 (1): 29–43. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.58470. ISSN 0301-4738. PMC 2841371. PMID 20029144.

- ↑ "Rubella vaccines: WHO position paper" (PDF). Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 86 (29): 301–16. 15 July 2011. PMID 21766537. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ↑ "Congenital Rubella - Pediatrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |