Astroviridae

| Astroviridae | |

|---|---|

| |

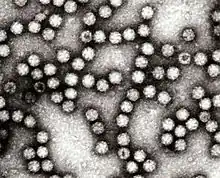

| Electron micrograph of Astroviruses | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Stelpaviricetes |

| Order: | Stellavirales |

| Family: | Astroviridae |

| Taxa | |

|

Genus: Avastrovirus

Genus: Mamastrovirus

| |

Astroviridae is a family of non-enveloped ssRNA viruses that cause infections in different animals.[1] The family name is derived from the Greek word astron ("star") referring to the star-like appearance of spikes projecting from the surface of these small unenveloped viruses.[2] Astroviruses were initially identified in humans but have since been isolated from other mammals and birds. This family of viruses consists of two genera, Avastrovirus (AAstV) and Mamastrovirus (MAstV).[3] Astroviruses most frequently cause infection of the gastrointestinal tract but in some animals they may result in encephalitis (humans and cattle), hepatitis (avian) and nephritis (avian).[4]

Astroviruses were first identified in humans in 1975 from the stool of children with diarrhea. Human infections are usually self-limiting but may also spread systematically and infect immunocompromised individuals.[5]

Taxonomy

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) established Astroviridae as a viral family in 1995.[6] There have been over 50 astroviruses reported, although the ICTV officially recognizes 22 species.[7] The genus Avastrovirus comprises three species: Chicken astrovirus (Avian nephritis virus types 1 - 3), Duck astrovirus (Duck astrovirus C-NGB), and Turkey astrovirus (Turkey astrovirus 1). The genus Mamastrovirus includes Bovine astroviruses 1 and 2, Human astrovirus (types 1-8), Feline astrovirus 1, Porcine astrovirus 1, Mink astrovirus 1 and Ovine astrovirus 1.[7]

Types

Avastrovirus

Avastroviruses are members of the Astroviridae family that infect birds.[7] Avastrovirus 1-3 are associated with enteric infections in turkeys, ducks, chicken and guinea fowl. In turkey poults 1-3 weeks of age, some symptoms of enteritis include diarrhea, listlessness, liver eating and nervousness. These symptoms are usually mild but in cases of poult enteritis and mortality syndrome (PEMS), which has dehydration, immune dysfunction and anorexia as symptoms, mortality is high.[8] Post mortem examination of the intestines of infected birds show fluid filled intestines. Hyperplasia of enterocytes is also observed in histopathology studies. However, in contrast to other enteric viruses, there isn't villous supply.[4]

Avastrovirus species often infect extraintestinal sites such as the kidney or liver resulting in hepatitis and nephritis.[4] Birds infected by avian nephritis virus typically die within 3 weeks of infection. The viral particles can be detected in fecal matter within 2 days and peak virus shedding occurs 4-5 days after infection.[9] The virus can be found in the kidney, jejunum, spleen, liver and bursa of infected birds. Symptoms of this disease include diarrhea and weight loss. Necropsies show swollen and discolored kidneys and there is evidence of death of the epithelial cells and lymphocytic interstital nephritis.[4] Another extraintestinal avastrovirus is avian hepatitis virus which infects ducks. Hepatitis in ducks caused by this Duck astrovirus (DAstV) is often fatal.[10]

In birds, Avastroviruses are detected by antigen-capture ELISA. In the absence of vaccines, sanitation is the prevalent way to prevent Avastrovirus infections.[4]

Mamastrovirus

Mamastroviruses often cause gastroenteritis in infected mammals. In animals, gastroenteritis is usually undiagnosed because most astrovirus infections are asymptomatic. However, in mink and humans, astroviruses can cause diarrhea and can be fatal. The incubation period for Mamastrovirus is 1-4 days. When symptoms occur, the incubation period is followed by diarrhea for several days. In mink, symptoms include increased secretion from apocrine glands.[4] Human astroviruses are associated with gastroenteritis in children and immunocompromised adults. [11] 2-8% of acute non-bacterial gastroenteritis in children is associated with human astrovirus. These viral particles are usually detected in epithelial cells of the duodenum.[4] In sheep, ovine astroviruses were found in the villi of the small intestine.[7]

Mamastroviruses also cause diseases of the nervous system.[12] These diseases most commonly occur in cattle, mink and humans. In cattle, this occurs sporadically and infects individual animals. Symptoms of this infection include seizure, lateral recumbency and impaired coordination. Histological examinations showed neuronal necrosis and gliosis of the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, spinal cord and brainstem.[13]

Morphology

Astroviruses are 28-30 nm non-enveloped viruses with T-3 icosahedral symmetry. They have spherical shapes and consist of a capsid protein shell. Astroviruses have distinctive five or six pointed star-like projections on 10% of the virions (the other virions have smooth surfaces).[4] The virion capsid is expressed from a subgenomic mRNA and its precursor undergoes multiple cleavages to make the VP70 protein. Capsids that are made of the VP70 protein are cleaved by trypsin to make particles that are very infectious (VP25/26, VP27/29 and VP34). The spikes that create the star-like appearance on the virion surface are made by two structural proteins (VP25 and VP27) while the capsid shell is made from VP34.[14]

Genome

Astrovirus genomes are positive sense single stranded RNA of 6.4-7.4 kb.[4] The genomes have a 3' polyadenylated end but lack a 5' cap. The 5' and 3' ends have untranslated regions with lengths that vary depending on the strain. Astrovirus genomes have three overlapping reading frames (ORFs) that code for polyproteins. ORF1a and ORF 1b are found at the 5' end while ORF2 is found at the 3' end. ORF1a and ORF1b cover half of the genome and they both encode the non-structural proteins such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, membrane associated proteins, Nucleoside triphosphate binding protein (NTP-binding protein) and proteases which play different roles in RNA transcription and replication. ORF2 encodes structural proteins.[15]

Replication

Replication of astroviruses occur in the cytoplasm.[16] Astrovirus RNA is infectious and functions as a messenger RNA for ORF1a and ORF1b.[17] A frame-shifting mechanism between these two nonstructural polypeptides translates RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.[18] In replication complexes near intracellular membranes, ORF1a and ORF1b are cleaved to generate individual nonstructural proteins that are involved in replication. The resulting subgenomic RNA contains ORF2 and encodes precursor capsid protein (VP90). VP90 is proteolytically cleaved during packaging and produces immature capsids made of VP70. Following encapsidation, immature capsids are released from the cell without lysis.[6] Extracellular virions are cleaved by Trypsin and form mature infectious virions.[19]

References

- ↑ Brown, David W.; Gunning, Kerry B.; Henry, Dorothy M.; Awdeh, Zuheir L.; Brinker, James P.; Tzipori, Saul; Herrmann, John E. (1 January 2008). "A DNA oligonucleotide microarray for detecting human astrovirus serotypes". Journal of Virological Methods. 147 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.07.028. ISSN 0166-0934. PMC 2238180. PMID 17905448.

- ↑ Krishna, Neel K. (1 March 2005). "Identification of Structural Domains Involved in Astrovirus Capsid Biology". Viral Immunology. 18 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1089/vim.2005.18.17. ISSN 0882-8245. PMC 1393289. PMID 15802951.

- ↑ Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. (2012) Ed: King, A.M.Q., Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B. and Lefkowitz, E.J. San Diego: Elsevier.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dubovi, Edward J. (30 November 2016). Fenner's Veterinary Virology (Fifth ed.). ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ↑ Wunderli, Werner; Meerbach, Astrid; Guengoer, Tayfun; Berger, Christoph; Greiner, Oliver; Caduff, Rosmarie; Trkola, Alexandra; Bossart, Walter; Gerlach, Daniel; Schibler, Manuel; Cordey, Samuel (11 November 2011). "Astrovirus Infection in Hospitalized Infants with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e27483. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...627483W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027483. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3214048. PMID 22096580.

- 1 2 Bosch, Albert; Pintó, Rosa M.; Guix, Susana (2014). "Human Astroviruses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 27 (4): 1048–1074. doi:10.1128/CMR.00013-14. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 4187635. PMID 25278582.

- 1 2 3 4 "Astroviridae - Positive Sense RNA Viruses - Positive Sense RNA Viruses (2011)". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ↑ Jindal, N.; Patnayak, D. P.; Ziegler, A. F.; Lago, A.; Goyal, S. M. (2009). "Experimental reproduction of poult enteritis syndrome: Clinical findings, growth response, and microbiology". Poultry Science. 88 (5): 949–958. doi:10.3382/ps.2008-00490. ISSN 0032-5791. PMC 7107170. PMID 19359682.

- ↑ Diseases of Poultry. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. 2013. ISBN 9781118720028.

- ↑ Fu, Yu; Pan, Meng; Wang, Xiaoyan; Xu, Yongliang; Xie, Xiaoyu; Knowles, Nick J.; Yang, Hanchun; Zhang, Dabing (2009). "Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings". Journal of General Virology. 90 (5): 1104–1108. doi:10.1099/vir.0.008599-0. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 19264607.

- ↑ Cortez, Valerie; Freiden, Pamela; Gu, Zhengming; Adderson, Elisabeth; Hayden, Randall; Schultz-Cherry, Stacey (2017). "Persistent Infections with Diverse Co-Circulating Astroviruses in Pediatric Oncology Patients, Memphis, Tennessee, USA - Volume 23, Number 2—February 2017 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (2): 288–290. doi:10.3201/eid2302.161436. PMC 5324824. PMID 28098537. S2CID 3589325.

- ↑ Bouzalas, Ilias G.; Wüthrich, Daniel; Walland, Julia; Drögemüller, Cord; Zurbriggen, Andreas; Vandevelde, Marc; Oevermann, Anna; Bruggmann, Rémy; Seuberlich, Torsten (2014). Onderdonk, A. B. (ed.). "Neurotropic Astrovirus in Cattle with Nonsuppurative Encephalitis in Europe". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (9): 3318–3324. doi:10.1128/JCM.01195-14. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 4313157. PMID 24989603.

- ↑ Bouzalas, Ilias G.; Wüthrich, Daniel; Walland, Julia; Drögemüller, Cord; Zurbriggen, Andreas; Vandevelde, Marc; Oevermann, Anna; Bruggmann, Rémy; Seuberlich, Torsten (2014). "Neurotropic Astrovirus in Cattle with Nonsuppurative Encephalitis in Europe". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (9): 3318–3324. doi:10.1128/JCM.01195-14. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 4313157. PMID 24989603.

- ↑ Arias, Carlos F.; DuBois, Rebecca M. (19 January 2017). "The Astrovirus Capsid: A Review". Viruses. 9 (1): 15. doi:10.3390/v9010015. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 5294984. PMID 28106836.

- ↑ Payne, Susan (2017). Family Astroviridae. Academic Press. ISBN 9780128031094.

- ↑ Dong, Jinhui; Dong, Liping; Méndez, Ernesto; Tao, Yizhi (2 August 2011). "Crystal structure of the human astrovirus capsid spike". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (31): 12681–12686. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10812681D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104834108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3150915. PMID 21768348.

- ↑ Geigenmüller, U.; Ginzton, N. H.; Matsui, S. M. (1 February 1997). "Construction of a genome-length cDNA clone for human astrovirus serotype 1 and synthesis of infectious RNA transcripts". Journal of Virology. 71 (2): 1713–1717. doi:10.1128/JVI.71.2.1713-1717.1997. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 191237. PMID 8995706.

- ↑ Marczinke, B.; Bloys, A. J.; Brown, T. D.; Willcocks, M. M.; Carter, M. J.; Brierley, I. (1 September 1994). "The human astrovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase coding region is expressed by ribosomal frameshifting". Journal of Virology. 68 (9): 5588–5595. doi:10.1128/JVI.68.9.5588-5595.1994. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 236959. PMID 8057439.

- ↑ Speroni, Silvia; Rohayem, Jacques; Nenci, Simone; Bonivento, Daniele; Robel, Ivonne; Barthel, Julia; Luzhkov, Victor B; Coutard, Bruno; Canard, Bruno; Mattevi, Andrea (17 April 2009). "Structural and Biochemical Analysis of Human Pathogenic Astrovirus Serine Protease at 2 Resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 387 (5): 1137–1152. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.044. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 19249313.