Caliciviridae

| Caliciviridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Caliciviridae |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

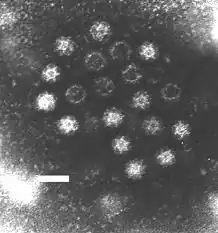

The Caliciviridae are a family of "small round structured" viruses, members of Class IV of the Baltimore scheme. Caliciviridae bear resemblance to enlarged picornavirus and was formerly a separate genus within the picornaviridae.[1] They are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA which is not segmented.[2] Thirteen species are placed in this family, divided among eleven genera.[3] Diseases associated with this family include feline calicivirus (respiratory disease), rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (often fatal hepatitis), and Norwalk group of viruses (gastroenteritis).[3][4] Caliciviruses naturally infect vertebrates, and have been found in a number of organisms such as humans, cattle, pigs, cats, chickens, reptiles, dolphins and amphibians. The caliciviruses have a simple construction and are not enveloped. The capsid appears hexagonal/spherical and has icosahedral symmetry (T=1[5] or T=3[6][4]) with a diameter of 35–39 nm.[7]

Caliciviruses are not very well studied because until recently, they could not be grown in culture, and they have a very narrow host range and no suitable animal model. However, the recent application of modern genomic technologies has led to an increased understanding of the virus family.[7] A recent isolate from rhesus monkeys—Tulane virus—can be grown in culture, and this system promises to increase understanding of these viruses.[8]

Taxonomy

The following genera are recognized:[9]

- Bavovirus

- Lagovirus

- Minovirus

- Nacovirus

- Nebovirus

- Norovirus

- Recovirus

- Salovirus

- Sapovirus

- Valovirus

- Vesivirus

A number of other caliciviruses remain unclassified, including the chicken calicivirus.

Virology

All viruses in this family possess a nonsegmented, polyadenylated, positive-sense, single-strand RNA genome around 7.5–8.5 kilobases in length, enclosed in an icosahedral capsid of 27–40 nanometers in diameter.

Life cycle

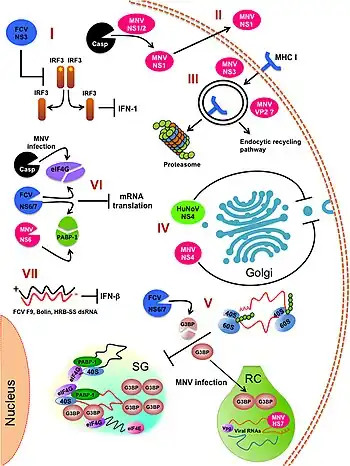

Viral replication is cytoplasmic. Entry into the host cell is achieved by attachment to host receptors, which mediate endocytosis. Replication follows the positive-stranded RNA virus replication model. Positive-stranded RNA virus transcription is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by leaky scanning, and RNA termination-reinitiation. Vertebrates serve as the natural host. Transmission routes are fecal-oral.[4]

Human disease

Calicivirus infections commonly cause moderate to severe gastroenteritis, which is the inflammation of the stomach and intestines (e.g. the Norwalk virus). Symptoms can include vomiting and diarrhea. These symptoms emerge after an incubation time of 2 days and the symptoms only generally last for 3 days. Most calicivirus infections do not require medical intervention, but those who are immunocompromised may need to be hospitalized due to serious fluid loss.

History

Establishing the viral etiology took many decades due to the difficulty of growing the virus in cell culture. In the 1940s and 1950s in the United States and Japan, caliciviridae could not be grown in culture, but as an experiment bacterial free filtrate of diarrhea was given to volunteers to check if viruses were present in volunteers' stool.[11]

These experiments demonstrated that nonbacterial, filterable agents had the capability of causing enteric disease in humans.[11] In 1968, an outbreak at a Norwalk elementary school (e.g. Norwalk virus) in Ohio led to stool samples again being given to volunteers and serially passaged to other people. Finally, in 1972, Kapikian and his colleagues isolated the Norwalk virus from volunteers using immune electron microscopy, a process that involves looking directly at antibody-antigen complexes.[11]

The classification of this one Norwalk virus strain served as the prototype for other species and small round structured viruses later known as Norovirus.[11]

Animal viruses

Feline calicivirus (FCV)—a member of the Vesivirus—represents an important pathogen of cats.

Sapovirus, Norovirus, and Vesivirus have been detected in pigs, making this animal species of particular interest in the study of calicivirus pathogenesis and host range.

The first mouse norovirus, murine norovirus 1 (MNV-1), was discovered in 2003. Since then, numerous murine norovirus strains have been identified and they were assigned a new genogroup in the genus Norovirus.

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus is a pathogen of rabbits that causes major problems throughout the world where rabbits are reared for food and clothing, make a significant contribution to ecosystem ecology, and where they support valued wildlife as a food source.[7]

Etymology

Calici- comes from the Latin word Calyx and the Greek word kalyx. The words mean a cup or chalice, a Calix. This comes from the strains having visible cup-shaped depressions.

Uses

Australia and New Zealand, in an effort to control their rabbit populations, have intentionally spread rabbit calicivirus.

References

- ↑ "Caliciviridae - Caliciviridae - Positive-sense RNA Viruses - ICTV". talk.ictvonline.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ↑ Vinjé, J; Estes, MK; Esteves, P; Green, KY; Katayama, K; Knowles, NJ; L'Homme, Y; Martella, V; Vennema, H; White, PA; ICTV Report Consortium (November 2019). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Caliciviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 100 (11): 1469–1470. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001332. PMC 7011698. PMID 31573467.

- 1 2 "ICTV Report Caliciviridae". Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "T=1". Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ "T=3". Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 Hansman, GS, ed. (2010). Caliciviruses: Molecular and Cellular Virology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-63-9.

- ↑ Yu G, Zhang D, Guo F, Tan M, Jiang X, Jiang W (2013). "Cryo-EM structure of a novel calicivirus, Tulane Virus". PLoS One 8(3):e59817. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059817

- ↑ "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ↑ Peñaflor-Téllez, Yoatzin; Trujillo-Uscanga, Adrian; Escobar-Almazán, Jesús Alejandro; Gutiérrez-Escolano, Ana Lorena (2019). "Immune Response Modulation by Caliciviruses". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 2334. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02334. ISSN 1664-3224.

- 1 2 3 4 Themes, U. F. O. (11 August 2016). "Caliciviridae: The Noroviruses". Basicmedical Key. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

External links

- ICTV Report: Caliciviridae Archived 29 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Caliciviridae description page from the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses site

- MicrobiologyBytes: Caliciviruses

- Human caliciviruses

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Caliciviridae

- Viralzone: Caliciviridae Archived 21 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- 3D macromolecular structures of Caliciviridae from the EM Data Bank(EMDB) Archived 21 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ICTV Archived 10 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine