Viral encephalitis

| Viral encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| |

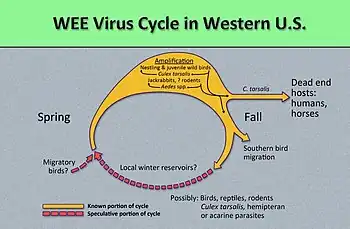

| This diagram illustrates the methods by which the arbovirus, Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV) reproduces and amplifies itself in both avian populations, and rodent populations, and is subsequently transmitted to dead end hosts including humans and horses by the Culex tarsalis mosquito. Western equine encephalitis virus, is a member of the family Togaviridae, and the genus Alphavirus, is closely related to Eastern and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses. | |

Viral encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma, called encephalitis, by a virus. The different forms of viral encephalitis are called viral encephalitides. It is the most common type of encephalitis and often occurs with viral meningitis. Encephalitic viruses first cause infection and replicate outside of the central nervous system (CNS), most reaching the CNS through the circulatory system and a minority from nerve endings toward the CNS. Once in the brain, the virus and the host's inflammatory response disrupt neural function, leading to illness and complications, many of which frequently are neurological in nature, such as impaired motor skills and altered behavior.

Viral encephalitis can be diagnosed based on the individual's symptoms, personal history, such as travel history, and different clinical tests such as histology, medical imaging, and lumbar punctures. A differential diagnosis can also be done to rule out other causes of the encephalitis. Many encephalitic viruses often have characteristic symptoms of infection, helping to aid diagnosis. Treatment is usually supportive in nature while also providing antiviral drug therapy. The primary exception to this is herpes simplex encephalitis, which is treatable with acyclovir. Prognosis is good for most individuals who are infected by an encephalitic virus but is poor among those who develop severe symptoms, including viral encephalitis. Long-term complications of viral encephalitis typically relate to neurological damage, such as experiencing seizures, memory loss, and intellectual impairment.

Encephalitic viruses are typically transmitted either from person-to-person or are arthropod-borne viruses, called arboviruses. The young and the elderly are at the highest risk of viral encephalitis. Many cases of viral encephalitis are not identified either because of lack of testing or mild illness, and serological surveys indicate that asymptomatic infections are common. Various ways of preventing viral encephalitis exist, such as vaccines that are either in standard vaccination programs or which are recommended when living in or visiting certain regions, and various measures aimed at preventing mosquito, sandfly, and tick bites in order to prevent arbovirus infection.

Signs and symptoms

In terms of the clinical presentation of this condition we find the following:[1]

- Fever

- Headache

- Seizures

- Altered mental status

- Hallucinations

Etiology

Many viruses are capable of causing encephalitis during infection, including:[1]

- California encephalitis virus[2]

- Chandipura virus[3]

- Chikungunya virus[4]

- Cytomegalovirus

- Dengue virus

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- Enteroviruses

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Herpes simplex virus

- HIV[5]

- Human herpesvirus 6

- Human herpesvirus 7

- Influenza viruses[4][6]

- Inkoo virus[7]

- Jamestown Canyon virus[8]

- Japanese encephalitis virus

- La Crosse virus

- Lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus[9]

- Measles virus

- Mumps virus

- Murray Valley encephalitis virus[10]

- Nipah virus

- Powassan virus[8]

- Rabies virus

- Rubella virus

- SARS-CoV-2[11]

- Snowshoe hare virus[7]

- St. Louis virus

- Tahyna virus[7]

- Tick-borne encephalitis virus

- Varicella-zoster virus, which causes both chickenpox and shingles

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus

- West Nile virus

- Western equine encephalitis virus

- Zika virus

Transmission

Encephalitic viruses vary in their manner of transmission. Some are transmitted from person-to-person, whereas others are transmitted by animals, especially bites from arthropods such as mosquitos, sandflies, and ticks, such viruses being called arboviruses.[12] An example of person-to-person transmission is the herpes simplex virus, which is transmitted by means of intimate physical contact.[13] An example of arboviral transmission is the West Nile virus, which usually is incidentally transmitted to people from the bites of Culex mosquitos, especially Culex pipiens.[14]

Pathogenesis

Viruses that cause viral encephalitis first infect the body and replicate outside of the central nervous system (CNS). Thereafter, most reach the spinal cord and brain via the circulatory system. Exceptions to this include herpesviruses and the rabies virus, which travel from nerve endings to the CNS. Once in the brain, the virus and the host's inflammatory response disrupt neural cell function, including causing fluid buildup in the brain, vascular congestion, and bleeding. Widespread presence of white blood cells and microglia in the CNS is common as a response to CNS infection. For some forms of viral encephalitis, such as Eastern equine encephalitis and Japanese encephalitis, there may be a significant amount of necrosis of nerve cells. Following encephalitis caused by arboviruses, calcification may occur in the CNS, especially among children. Herpes simplex encephalitis tends to produce necrotic lesions in the CNS.[1]

Diagnosis

Examination

If viral encephalitis is suspected, then questions can be asked about the individual's history and physical examination can be performed. Important aspects of one's history include immune status, exposure to animals, including insects, travel history, vaccination history, geography, and time of year. Symptoms usually occur acutely,[4] and the most common symptoms of infection are fever, headache, altered mental status, sensitivity to light, stiff neck and back, vomiting, confusion, and, in severe cases, seizures, paralysis, and coma. Neuropsychiatric features such as behavioral changes, hallucinations, or cognitive decline are frequent. Severe symptoms are most common among infants and the elderly. Most infections are asymptomatic, lacking symptoms, whereas most symptomatic cases are mild illnesses.[1][12]

Virus-specific symptoms may also exist or tests may indicate one virus. Specific examples include:[1]

- Enterovirus 71 may cause tremors, twitching, impaired balance and coordination, fluid accumulation in the lungs, and cranial nerve palsies.

- Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis is usually accompanied by enlargement of the lymph nodes and enlargement of the spleen

- Herpes zoster encephalitis may be accompanied by rash and skin vesicles, and because it involves the frontal lobe and temporal lobe, is often characterized by psychiatric features, memory deficits, and loss of language faculties.

- Many arboviral encephalitides, such as Japanese encephalitis, primarily affect the basal ganglia, sometimes causing motor symptoms such as involuntary movements and movements similar to those observed in Parkinson's disease.

- Nipah virus may produce brainstem and cerebellar signs, hypertension, and segmental myoclonus, or twitching of a group of connected muscles.

- Zika virus characteristically may cause microcephaly among newborn children if a pregnant woman is infected.

Histology

The brain histology of viral encephalitis shows dead neurons with nuclear dissolution and elevated eosinophil count, called hypereosinophilia, within cells' cytoplasm when viewed with an optical microscope. Because encephalitis is an inflammatory response, inflammatory cells situated near blood vessels, such as microglia, macrophages, and lymphocytes, are visible. Virions within neurons are visible via electron microscopes.[1]

Clinical evaluation

| Virus | Preferred diagnostic test |

|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus | CSF PCR or CSF-specific IgM |

| Dengue/Chikungunya/Zika | CSF PCR or CSF-specific IgM |

| Enterovirus | Stool and throat PCR are preferred over CSF PCR |

| Epstein-Barr virus | Serum EBV capsid antigen IgG and IgM (VCA) and EBV nuclear antigen IgG (EBNA) |

| Herpes simplex virus | CSF PCR, can be repeated within 2 to 7 days of disease onset if negative with high clinical suspicion; or CSF for HSV-IgG after 10–14 days of disease onset |

| HHV-6 | CSF PCR paired with serum PCR to exclude viral integration into host DNA that causes false positives |

| Influenza | Culture, antigen test, PCR of respiratory secretions |

| Measles | CSF-specific IgG |

| Varicella-zoster virus | CSF-specific IgG |

Neuroimaging and lumbar puncture (LP) are both essential methods of diagnosing viral encephalitis. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) help identify increased intracranial pressure and the risk of uncal herniation before performing an LP. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), if analyzed, should be analyzed for opening pressure, cell counts, glucose, protein, and IgG and IgM antibodies. CSF testing should also include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 and enteroviruses. About 10% of patients have normal CSF results. Additional testing, such as serology for various arboviruses and HIV testing, may also be performed based on the individual's history and symptoms. Brain biopsy and body fluid specimen cultures and PCR may also be useful in some cases. Electroencephalography (EEG) is abnormal in more than 80% of viral encephalitis cases, including those who are experiencing seizures, and may need to be monitored continuously to identify non-convulsive status. Lack of testing resources may prevent accurate diagnosis.[1][4]

Test results specific to certain viruses include:[1]

- For herpes simplex virus encephalitis, a CT scan may show low-density lesions in the temporal lobe. These lesions usually appear 3 to 5 days after the start of the infection.

- Japanese encephalitis often has distinct EEG patterns, including diffuse delta activity with spikes, diffuse continuous delta activity, and alpha coma activity.

Differential diagnosis

A broad differential diagnosis can be performed that looks at many potential causes of the encephalitis, infectious and noninfectious. Potential alternatives to viral encephalitis include malignancy, autoimmune or paraneoplastic diseases such as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, a brain abscess, tuberculosis or drug-induced delirium, exposure to certain drugs or toxins, neurosyphilis, vascular disease, metabolic disease, or encephalitis from infection caused by a bacterium, fungus, protozoan, or parasitic worm.[1][6][13] In children, differential diagnosis may not be able to distinguish between viral encephalitis and immune-mediated inflammatory CNS diseases, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, as well as immune-mediated encephalitis, so other diagnostic methods may need to be used.[4]

Prevention

As many encephalitic viruses are transmitted by mosquitos, many prevention efforts revolve around preventing mosquito bites. In areas where such arboviruses are widespread, people should use protective clothing and should sleep under a mosquito net. Removing containers of stagnant water and spraying insecticides can be beneficial. Activities that increase the likelihood of tick bites should be avoided. Vaccines against some arboviruses that cause viral encephalitis exist, such as those against Eastern equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Although these vaccines are not perfectly effective, they are recommended for people who live in or travel to high-risk areas.[1][6] Some vaccines that are included in standard vaccination programs, such as the MMR vaccine, which prevents measles, mumps, and rubella, are also capable of preventing viral encephalitis.[15]

Treatment

Treatment of viral encephalitis is primarily supportive with intravenous antiviral therapy due to there being no specific medical therapy for most viral infections involving the central nervous system. Individuals may require intensive care for frequent neurological exams or respiratory support, and treatment for electrolyte disturbance, autonomic disregulation, and renal and hepatic dysfunction, as well as for seizures and non-compulsive status epilepticus.[1][4]

A very specific exception is herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis, which can be treated with acyclovir for 2 to 3 weeks if it is provided early enough. Acyclovir significant decreases morbidity and mortality of HSV encephalitis and limits the long-term behavioral and cognitive impairments that occur with illness. As such, and because HSV is the most common cause of viral encephalitis, acyclovir is often administered as soon as possible to all patients suspected of having viral encephalitis even if the exact viral origin is not yet known. Viral resistance to acyclovir rarely occurs, primarily among the immunocompromised, in which case foscarnet should be used. Although not as effective, nucleoside analogs are used for other herpesviruses as well, such as acyclovir, with possible adjunctive corticosteroids for immunocompetent individuals, for varicella-zoster virus encephalitis and a combination of ganciclovir and foscarnet for cytomegalovirus encephalitis.[1][13]

Serial intracranial pressure (ICP) is important to monitor as elevated ICP is associated with poor prognosis. Elevated ICP can be relieved with steroids and mannitol, though there is limited data of the efficacy of such treatment with regards to viral encephalitis. Seizures can be managed with valproic acid or phenytoin. Status epilepticus may required benzodiazepines. Antipsychotic drugs may be needed for a short time period if behavior alternations are present. Given the possibility of complications developing from viral encephalitis, an interdisciplinary team consisting of the clinicians, therapists, rehabilitation specialists, and speech therapists is important in order to help patients.[1]

Prognosis

If treated, most individuals recover from viral encephalitis without long-term problems related to the illness. Mortality rates vary for those who do not receive treatment, for example being about 70% for herpes encephalitis[13] but low for the La Crosse virus. Individuals who remain symptomatic after initial infection may have difficulty concentrating, behavior or speech disorders, or memory loss. Rarely, individuals may remain in a persistent vegetative state. The most common long-term complication of viral encephalitis is seizures that may occur in 10% to 20% of patients over several decades. These seizures are resistant to medical therapy. However, individuals who have unilateral mesial temporal lobe seizures after viral encephalitis have good results following neurosurgery. Prognoses related to specific viruses include:[1]

- For Eastern equine encephalitis, some children may experience seizures, severe mental retardation, and various forms of paralysis.

- For Japanese encephalitis, extrapyramidal symptoms relating to motor function may remain.

- For St. Louis encephalitis, low blood sodium level and excess, unsuppressable release of antidiuretic hormone

- For Western equine encephalitis, some children may experience seizures and behavioral changes.

- For pregnant women infected with Zika virus, the newborn child may have microcephaly.

Other potential complications following viral encephalitis include:[1]

- Encephalopathy

- Flaccid paralysis

- Impaired intelligence

- Low blood sodium level

- Mononeuropathy

- Mood and behavioral changes

- Residual neurological deficits

Epidemiology

While the etiology of many cases of encephalitis is unknown, viruses account for about 70% of confirmed encephalitis cases, with the herpes simplex virus being the most common cause at about 50% of encephalitis cases.[13] The incidence of viral encephalitis is about 3.5 to 7.5 per 100,000 people, with the highest incidence among the young and the elderly. Viral encephalitis caused by some viruses, such as the measles virus and the mumps virus, has become less common due to widespread vaccination. For others, such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus, incidence has increased due to the increased prevalence of AIDS, organ transplantation, and chemotherapy, which have increased the number of immunocompromised people who have weakened immune systems or who are susceptible to opportunistic infections. Time of the year, geography, and animal, including insect, exposure are also important. For example, arbovirus infections are seasonal and cause viral encephalitis at the highest rate during the summer and early fall when mosquitos are most active. Similarly, those who live in warm, humid climates where there are more mosquitos are more likely to experience viral encephalitis.[1][6]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Said, S.; Kang, M. (16 December 2019). Viral encephalitis. StatPearls Publishing LLC. PMID 29262035. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ↑ Hammon, W. M.; Reeves, W. C. (1952). "California encephalitis virus, a newly described agent". Calif Med. 77 (5): 303–309. PMC 1521486. PMID 13009479.

- ↑ Ghosh, S.; Basu, A. (January–February 2017). "Neuropathogenesis by Chandipura virus: An acute encephalitis syndrome in India". Natl Med J India. 30 (1): 21–25. PMID 28731002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Costa, B. K. D.; Sato, D. K. (2020). "Viral encephalitis: a practical review on diagnostic approach and treatment". Jornal de Pediatria. 96 (Suppl. 1): 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2019.07.006. PMID 31513761. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ Chen, Z.; Zhong, D.; Li, G (2019). "The role of microglia in viral encephalitis: a review". J Neuroinflammation. 16 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/s12974-019-1443-2. PMC 6454758. PMID 30967139.

- 1 2 3 4 "Understanding encephalitis -- the basics". WebMD. WebMD. 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 Evans, A. B.; Winkler, C. W.; Peterson, K. E. (2019). "Differences in Neuropathogenesis of Encephalitic California Serogroup Viruses". Emerg Infect Dis. 25 (4): 728–738. doi:10.3201/eid2504.181016. PMC 6433036. PMID 30882310.

- 1 2 Pastula, D. M.; Smith, D. E.; Beckham, J. D.; Tyler, K. L. (2016). "Four emerging arboviral diseases in North America: Jamestown Canyon, Powassan, chikungunya, and Zika virus diseases". J Neurovirol. 22 (3): 257–260. doi:10.1007/s13365-016-0428-5. PMC 5087598. PMID 26903031.

- ↑ Lavergne, A.; de Thoisy, B.; Tirera, S.; Donato, D.; Bouchier, C.; Catzeflies, F.; Lacoste, V. (2016). "Identification of lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus in house mouse (Mus musculus, Rodentia) in French Guiana". Infect Genet Evol. 37: 225–230. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.023. PMID 26631809. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ Mackenzie, J. S.; Lindsay, M. D. A.; Smith, D. W.; Imrie, A (2017). "The ecology and epidemiology of Ross River and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses in Western Australia: examples of One Health in Action". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 111 (6): 248–254. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trx045. PMC 5914307. PMID 29044370.

- ↑ Carod-Artal, F. J. (1 May 2020). "Neurological Complications of Coronavirus and COVID-19". Revista de Neurología. 70 (9): 311–322. doi:10.33588/rn.7009.2020179. PMID 32329044.

- 1 2 "Encephalitis, Viral". World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradshaw, M. J.; Venkatesan, A. (2016). "Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Encephalitis in Adults: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management". Neurotherapeutics. 13 (3): 493–508. doi:10.1007/s13311-016-0433-7. PMC 4965403. PMID 27106239.

- ↑ "West Nile Virus". World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 3 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "Understanding encephalitis -- prevention". WebMD. WebMD. 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

External links

| Classification |

|---|