Herpesviral encephalitis

| Herpesviral encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSV encephalitis) | |

| |

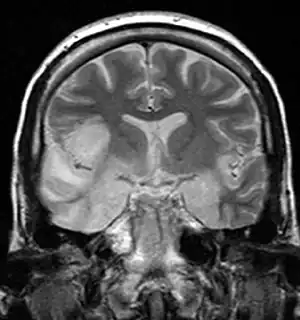

| Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows high signal in the temporal lobes including hippocampal formations and parahippogampal gyrae, insulae, and right inferior frontal gyrus due to HSV encephalitis. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, neurology |

| Symptoms | Headache, fever, confusion, weakness[1] |

| Complications | Autoimmune encephalitis[2] |

| Causes | Herpes simplex virus[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, MRI[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other causes of encephalitis, meningitis, neurosyphilis[1] |

| Treatment | Acyclovir[2] |

| Prognosis | 66% have ongoing disability[3] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

Herpesviral encephalitis is inflammation of the brain due to the herpes simplex virus.[1] Symptoms commonly include headache, fever, confusion, and weakness.[1] Less commonly neck stiffness and abnormal speech may occur.[1] Onset is generally over a couple of days.[1] Complications can include seizures, diabetes insipidus, and autoimmune encephalitis.[4][2]

It most commonly occurs due to herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), with less than 10% of cases due to herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2).[1][4] About a third of cases occur as an initial infection, while two thirds occur as a recurrence; though only 10% have a history of cold sores.[3] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms, supported by cerebral spinal fluid analysis and MRI.[2]

Treatment is with acyclovir.[2] Anticonvulsants may be used to decrease the risk of seizures.[1] The disease is most severe in the young and the old.[4] About 20% experience significant long term disability.[4] The risk of death is between 1% and 8%.[2]

Herpesviral encephalitis is rare, affects about 1 in 100,000 newborns, 1 in 400,000 children, and 1 in 150,000 adults in the United States.[2][1] Males and females are affected with similar frequencies.[1] About half of cases develop in those over the age of 50.[5] It is the most common cause of infectious encephalitis in the developed world.[2] The disease was first described in humans in 1935.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Most individuals with HSE show a decrease in their level of consciousness and an altered mental state presenting as confusion, and changes in personality. People typically have a fever[3] and may have seizures. The electrical activity of the brain changes as the disease progresses, first showing abnormalities in one temporal lobe of the brain, which spread to the other temporal lobe 7–10 days later.[3]

Atypical stroke-like presentation of HSV encephalitis has been described as well and the clinicians should be aware that HSV encephalitis can mimic a stroke. [7]

Associated conditions

Herpesviral encephalitis can serve as a trigger of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.[8]

Pathophysiology

HSE is thought to be caused by the transmission of virus from a peripheral site on the face following HSV-1 reactivation, along a nerve axon, to the brain.[3] The virus lies dormant in the ganglion of the trigeminal cranial nerve, but the reason for reactivation, and its pathway to gain access to the brain, remains unclear, though changes in the immune system caused by stress clearly play a role in animal models of the disease. The olfactory nerve may also be involved in HSE,[9] which may explain its predilection for the temporal lobes of the brain, as the olfactory nerve sends branches there. In horses, a single-nucleotide polymorphism is sufficient to allow the virus to cause neurological disease;[10] but no similar mechanism has been found in humans.

Diagnosis

Increased numbers of white blood cells can be found in person's cerebrospinal fluid, without the presence of pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Definite diagnosis requires testing of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) for presence of the virus. The testing takes several days to perform.

Imaging by CT or MRI shows characteristic changes in the temporal lobes. Brain CT scan (with/without contrast). Complete prior to lumbar puncture to exclude significantly increased ICP, obstructive hydrocephalus, mass effect.

Brain MRI—Increased T2 signal intensity in frontotemporal region → viral (HSV) encephalitis.

Treatment

Treatment is with acyclovir at a dose of 10 mg/kg (adult) by injection three times per day for 14 days.[2] Without treatment, HSE results in rapid death in approximately 70% of cases; survivors suffer severe neurological damage.[3] When treated, HSE is still fatal in one-third of cases, and causes serious long-term neurological damage in over half of survivors. Twenty percent of treated patients recover with minor damage. Only a small population of untreated survivors (2.5%) regain completely normal brain function.[5] Many amnesic cases in the scientific literature have etiologies involving HSE.

Earlier treatment (within 48 hours of symptom onset) improves the chances of a good recovery. Rarely, treated individuals can have relapse of infection weeks to months later. There is evidence that aberrant inflammation triggered by herpes simplex can result in granulomatous inflammation in the brain, which responds to steroids.[11] While the herpes virus can be spread, encephalitis itself is not infectious. Other viruses can cause similar symptoms of encephalitis, though usually milder (Herpesvirus 6, varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, etc.).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Encephalitis, Herpes Simplex". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Stahl, JP; Mailles, A (June 2019). "Herpes simplex virus encephalitis update". Current opinion in infectious diseases. 32 (3): 239–243. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000554. PMID 30921087.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Whitley RJ (September 2006). "Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults". Antiviral Research. 71 (2–3): 141–8. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.002. PMID 16675036.

- 1 2 3 4 AK, AK; Mendez, MD (January 2021). "Herpes Simplex Encephalitis". PMID 32491575.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Whitley RJ, Gnann JW (February 2002). "Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging pathogens". Lancet. 359 (9305): 507–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07681-X. PMID 11853816. S2CID 5980017.

- ↑ Grove, David (2013-12-19). Tapeworms, Lice, and Prions: A compendium of unpleasant infections. OUP Oxford. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-19-165344-5. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Dalmau J, Armangué T, Planagumà J, Radosevic M, Mannara F, Leypoldt F, Geis C, Lancaster E, Titulaer MJ, Rosenfeld MR, Graus F (November 2019). "An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models". The Lancet. Neurology. 18 (11): 1045–1057. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30244-3. PMID 31326280. S2CID 197464804.

- ↑ Dinn JJ (November 1980). "Transolfactory spread of virus in herpes simplex encephalitis". British Medical Journal. 281 (6252): 1392. doi:10.1136/bmj.281.6252.1392. PMC 1715042. PMID 7437807.

- ↑ Van de Walle GR, Goupil R, Wishon C, Damiani A, Perkins GA, Osterrieder N (July 2009). "A single-nucleotide polymorphism in a herpesvirus DNA polymerase is sufficient to cause lethal neurological disease". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 200 (1): 20–5. doi:10.1086/599316. PMID 19456260.

- ↑ Varatharaj A, Nicoll JA, Pelosi E, Pinto AA (April 2017). "Corticosteroid-responsive focal granulomatous herpes simplex type-1 encephalitis in adults". Practical Neurology. 17 (2): 140–144. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2016-001474. PMID 28153849. S2CID 12859405. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

External links

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |