Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

| Frontotemporal lobar degeneration | |

|---|---|

| |

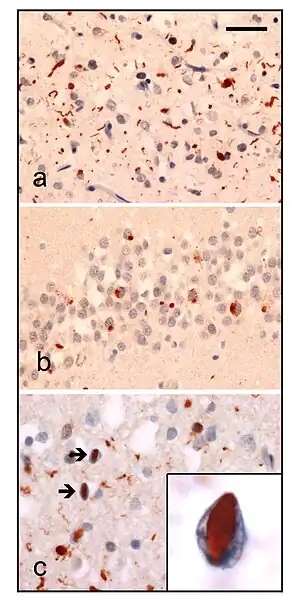

| Neuropathologic analysis of brain tissue from FTLD-TDP patients. Ubiquitin immunohistochemistry in cases of familial FTLD-TDP demonstrates staining of (a) neurites and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the superficial cerebral neocortex, (b) neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in hippocampal dentate granule cells, and (c) neuronal intranuclear inclusions in the cerebral neocortex (arrows). Scale bar; (a) and (b) 40 μm, (c) 25 μm, insert 6 μm. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

| Complications | Brain death |

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is a pathological process that occurs in frontotemporal dementia. It is characterized by atrophy in the frontal lobe and temporal lobe of the brain, with sparing of the parietal and occipital lobes.

Common proteinopathies that are found in FTLD include the accumulation of tau proteins and TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43). Mutations in the C9orf72 gene have been established as a major genetic contribution of FTLD, although defects in the granulin (GRN) and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) are also associated with it.[1]

Classification

There are 3 main histological subtypes found at post-mortem:

- FTLD-tau is characterised by tau positive inclusion bodies often referred to as Pick-bodies.[2] Examples of FTLD-tau include; Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy.

- FTLD-TDP (or FTLD-U ) is characterised by ubiquitin and TDP-43 positive, tau negative, FUS negative inclusion bodies. The pathological histology of this subtype is so diverse it is subdivided into four subtypes based on the detailed histological findings:

- Type A presents with many small neurites and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in the upper (superficial) cortical layers. Bar-like neuronal intranuclear inclusions can also be seen they are fewer in number.

- Type B presents with many neuronal and glial cytoplasmic inclusions in both the upper (superficial) and lower (deep) cortical layers, and lower motor neurons. However neuronal intranuclear inclusions are rare or absent. This is often associated with ALS and C9ORF72 mutations (see next section).

- Type C presents many long neuritic profiles found in the superficial cortical laminae, very few or no neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, neuronal intranuclear inclusions or glial cytoplasmic inclusions. This is often associated with semantic dementia.

- Type D presents with many neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites, and an unusual absence of inclusions in the granule cell layer of the hippocampus. Type D is associated with VCP mutations.

- Type E presents with neuronal granulofilamentous inclusions and abundant fine grains involving upper (superficial) and lower (deep) cortical layers. This has been associated with behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia with a rapid clinical course.[3]

Two groups independently categorized the various forms of TDP-43 associated disorders. Both classifications were considered equally valid by the medical community, but the physicians and researchers in question have jointly proposed a compromise classification to avoid confusion.[4]

- FTLD-FUS; which is characterised by FUS positive cytoplasmic inclusions, intra nuclear inclusions, and neuritic threads. All of which are present in the cortex, medulla, hippocampus, and motor cells of the spinal cord and XIIth cranial nerve.

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is the following:[5]

- Apathy

- Depression

- Cognitive impairment

- Dietary chages

- Behavioral changes

- Sleep disturbance

Genetics

There have been numerous advances in descriptions of genetic causes of FTLD, and the related disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

- Mutations in the Tau gene (known as MAPT or Microtubule Associated Protein Tau) can cause a FTLD presenting with tau pathology (FTLD-tau).[6] There are over 40 known mutations at present.

- Mutations in the Progranulin gene (PGRN) can cause a FTLD presenting with TDP-43 pathology (FTLD-TDP43). Patients with Progranulin mutations have type 3 ubiquitin-positive, TDP-43 positive, tau-negative pathology at post-mortem. Progranulin is associated with tumorgenesis when overproduced, however the mutations seen in FTLD-TDP43 produce a haploinsufficiency, meaning that because one of the two alleles is damaged, only half as much Progranulin is produced.[7]

- Mutations in the CHMP2B gene are associated with a rare behavioural syndrome akin to bvFTLD (mainly in a large Jutland cohort), presenting with a tau negative, TDP-43 negative, FUS negative, Ubiquitin positive pathology.

- Hypermorphic mutations in the VCP gene cause a TDP-43-positive FTLD which is associated with multisystem proteinopathy (MSP), also known as IBMPFD (inclusion body myopathy, Paget's disease and frontotemporal dementia)[8]

- A hypomorphic mutation in the VCP gene cause a unique type of FTLD-tau called vacuolar tauopathy with neurofibrillary tangles and neuronal vacuoles [9]

- Mutations in the TDP-43 gene (known as TARBP or TAR DNA-binding protein) are an exceptionally rare cause of FTLD, despite this protein being present in the pathological inclusions of many cases (FTLD-TDP43).[10] However, mutations in TARBP are a more common cause of ALS, which can present with frontotemporal dementia. Since these instances are not considered a pure FTLD they are not included here.

Mutations in all of the above genes cause a very small fraction of the FTLD spectrum. Most of the cases are sporadic (no known genetic cause).

- A proportion of FTLD-TDP43 [with ALS] cases had shown genetic linkage to a region on chromosome 9 (FTLD-TDP43/Ch9). This linkage has recently been pinned down to the C9ORF72 gene. Two groups published identical findings back-to-back in the journal Neuron in mid-2011, showing that a hexanucleotide repeat expansion of the GGGGCC genetic sequence within an intron of this gene was responsible. This expansion was found to be present in a large proportion of familial and sporadic cases, particularly in the Finnish population[11]

Diagnosis

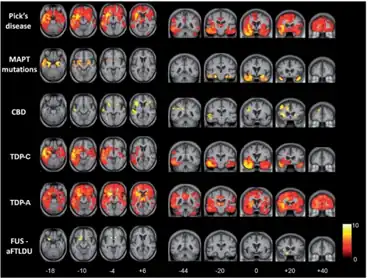

For diagnostic purposes, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ([18F]fluorodeoxyglucose) positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) are applied. They measure either atrophy or reductions in glucose utilization. The three clinical subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia and progressive nonfluent aphasia, are characterized by impairments in specific neural networks.[12] The first subtype with behavioral deficits, frontotemporal dementia, mainly affects a frontomedian network discussed in the context of social cognition. Semantic dementia is mainly related to the inferior temporal poles and amygdalae; brain regions that have been discussed in the context of conceptual knowledge, semantic information processing, and social cognition, whereas progressive nonfluent aphasia affects the whole left frontotemporal network for phonological and syntactical processing.

Treatment

There is currently only management of symptoms, with no specific treatment.[13]

Society

United States Senator Pete Domenici (R-NM) was a known sufferer of FTLD, and the illness was the main reason behind his October 4, 2007 announcement of retirement at the end of his term. American film director, producer, and screenwriter Curtis Hanson died as a result of FTLD on September 20, 2016.

See also

References

- ↑ van der Zee, Julie; Van Broeckhoven, Christine (7 January 2014). "Dementia in 2013: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration—building on breakthroughs". Nature Reviews Neurology. 10 (2): 70–72. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.270. PMID 24394289.

- ↑ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon C. (2018). Robbins basic pathology (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 877. ISBN 9780323353175.

- ↑ Lee, Edward B.; et al. (Jan 2017). "Expansion of the classification of FTLD-TDP: distinct pathology associated with rapidly progressive frontotemporal degeneration". Acta Neuropathol. 134 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1007/s00401-017-1679-9. PMC 5521959. PMID 28130640.

- ↑ Ian R. A. Mackenzie; Manuela Neumann; Atik Baborie; Deepak M. Sampathu; Daniel Du Plessis; Evelyn Jaros; Robert H. Perry; John Q. Trojanowski; David M. A. Mann & Virginia M. Y. Lee (July 2011). "A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology". Acta Neuropathol. 122 (1): 111–113. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0845-8. PMC 3285143. PMID 21644037.

- ↑ Vossel, Keith A.; Miller, Bruce L (December 2008). "New Approaches to the Treatment of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration". Current opinion in neurology. 21 (6): 708–716. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328318444d. ISSN 1350-7540. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ↑ Goedert, M.; et al. (1989). "Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding an isoform of microtubule-associated protein tau containing four tandem repeats: differential expression of tau protein mRNAs in human brain". The EMBO Journal. 8 (2): 393–9. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03390.x. PMC 400819. PMID 2498079.

- ↑ Cruts, M.; et al. (2006). "Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21". Nature. 442 (7105): 920–4. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..920C. doi:10.1038/nature05017. PMID 16862115. S2CID 4423699.

- ↑ Kimonis, V.E.; et al. (2008). "VCP disease associated with myopathy, Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia: review of a unique disorder" (PDF). Biochim Biophys Acta. 1782 (12): 744–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.003. PMID 18845250. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ↑ Darwich, N.F., Phan J.M.; et al. (2020). "Autosomal dominant VCP hypomorph mutation impairs disaggregation of PHF-tau". Science. 370 (6519): eaay8826. doi:10.1126/science.aay8826. PMC 7818661. PMID 33004675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Borroni, B.; et al. (2010). "TARDBP mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: frequency, clinical features, and disease course". Rejuvenation Res. 13 (5): 509–17. doi:10.1089/rej.2010.1017. PMID 20645878.

- ↑ Dejesus-Hernandez, M.; et al. (2011). "Expanded GGGGCC Hexanucleotide Repeat in Noncoding Region of C9ORF72 Causes Chromosome 9p-Linked FTD and ALS". Neuron. 72 (2): 245–56. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. PMC 3202986. PMID 21944778.

- ↑ Schroeter ML, Raczka KK, Neumann J, von Cramon DY (2007). "Towards a nosology for frontotemporal lobar degenerations – A meta-analysis involving 267 subjects". NeuroImage. 36 (3): 497–510. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.024. PMID 17478101. S2CID 130161.

- ↑ "Frontotemporal Degeneration". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

Bibliography

- Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, et al. (July, 2007). "Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration." Acta Neuropathologica..114 (1): 5-22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. PMID 17579875 Archived 2021-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cairns NJ, Grossman M, Arnold SE, Burn DJ, Jaros E, Perry RH, Duyckaerts C, Stankoff B, Pillon B, Skullerud K, Cruz-Sanchez FF, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Gearing M, Juncos JL, Glass JD, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y, Mosaheb S, Thorpe JR, Uryu K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. (October, 2004).Clinical and neuropathologic variation in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease. Neurology. 63 (8):1376-84. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000139809.16817.dd. PMID 15505152 Archived 2022-01-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S, et al. (November 2006). "Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype". Acta Neuropathologica. 112 (5): 539–49. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0138-9. PMC 2668618. PMID 17021754.

- Mackenzie IR, Munoz DG, Kusaka H, Yokota O, Ishihara K, Roeber S, Kretzschmar HA, Cairns NJ, Neumann M. (February, 2011). Distinct pathological subtypes of FTLD-FUS. Acta Neuropathologica..121 (2) :207-18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0764-0. PMID 21052700 Archived 2022-02-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- Davidson Y, Kelley T, Mackenzie IR, et al. (May 2007). "Ubiquitinated pathological lesions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration contain the TAR DNA-binding protein, TDP-43". Acta Neuropathologica. 113 (5): 521–33. doi:10.1007/s00401-006-0189-y. PMID 17219193. S2CID 22524747.

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. (December 1, 1998). "Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria". Neurology. 51 (6): 1546–54. doi:10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. PMID 9855500. S2CID 37238391. Archived from the original on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- Pickering-Brown SM (July 2007). "The complex aetiology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration". Experimental Neurology. 206 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.017. PMID 17509568. S2CID 1280814.

Further reading

- Hodges, John R. The Frontotemporal Dementia Syndromes. Cambridge University Press. 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-85477-1

- OMIM entries on FRONTOTEMPORAL DEMENTIA AND/OR AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS as well as C9ORF72 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Overview Archived 2022-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification |

|---|