Endomyocardial biopsy

| Endomyocardial biopsy | |

|---|---|

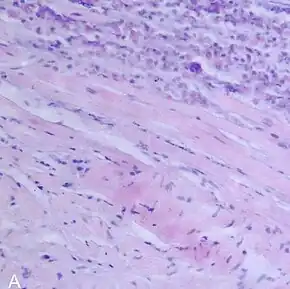

Endomyocardial biopsy showing myocarditis | |

| Purpose | Surveillance of allograft rejection following heart transplantation |

Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) is an invasive procedure used routinely to obtain small samples of heart muscle, primarily for detecting rejection of a donor heart following heart transplantation. It is also used as a diagnostic tool in some heart diseases.[1]

A bioptome is used to gain access to the heart via a sheath inserted into the right internal jugular or less commonly the femoral vein.[1] Monitoring during the procedure consists of performing ECGs and blood pressures.[1] Guidance and confirmation of correct positioning of the bioptome is made by echocardiography or fluoroscopy.[1]

The risk of complications is less than 1% when performed by an experienced physician in a specialist centre.[1] Serious complications include perforation of the heart with pericardial tamponade, haemopericardium, AV block, tricuspid regurgitation and pneumothorax.[2]

EMB, sampling myocardium was first pioneered in Japan by S. Sakakibra and S. Konno in 1962.[1][3]

Indications

The main reason for performing an EMB is to assess allograft rejection following heart transplantation and sometimes to evaluate cardiomyopathy, some heart disease research and ventricular arrhythmias,[4] or unexplained ventricular dysfunction.[5][6]

Transplant monitoring

Visualising the microscopic appearance of the heart muscle allows the detection of cell-mediated or antibody-mediated rejection and is recommended episodically during the first year after heart transplantation. Occasionally, monitoring continues beyond one year.[1]

The use of EMB in heart transplant rejection surveillance remains the gold standard test, although the pre-test predictors of rejection cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and gene expression profiling, are increasingly used.[1]

Myocardial diseases

EMB has a role in the diagnosis of viral myocarditis and inflammatory myocarditis.[1]

Procedure

EMB of the right ventricle via the internal jugular vein is standard after heart transplant. [4] A bioptome is used to gain access to the heart via a sheath inserted into the right internal jugular or less commonly the femoral vein.[1] Monitoring during the procedure consists of performing ECGs and blood pressures. Guidance and confirmation of correct positioning of the bioptome is made by echocardiography or fluoroscopy[1] before the biopsy specimen is taken and in the case of transplants, usually three[4] or four or more samples are taken.[1]

Endomyocardial fibrosis can occur if biopsies are performed repeatedly. This risk is reduced if the operator is experienced. Unlike for rejection detection, for diagnosing heart disease, different biopsy sites within the heart are targeted.[4]

It is possible but less common to biopsy the left ventricle via the femoral arteries.[1]

Limitations

The accuracy of diagnosis by EMB depends on whether the correct site is biopsied. There is a risk that a diagnosis can be missed if the biopsy misses the diseased part of heart muscle, particularly with myocardial inflammation or fibrosis.[5][8]

An experienced pathologist trained in biopsy analysis and interpretation also reflects EMB’s reliability. Variability between pathologists has been observed. [4]

Complications

A frequent concern regarding EMB has been its safety.[1] However, it has a low risk of less than 1% when performed by an experienced physician in a specialist centre.[1][3]

Possible complications, which almost all occur at time of procedure,[4] include rupture of the right intraventricular septum, conduction block, arrhythmias, pneumothorax, tricuspid regurgitation, and pulmonary embolism. Death has been reported, but is rare.[1]

History

Early heart biopsies, sampling pericardium, in the latter half of the 1950s were performed through a cut in the left intercostal space at the costochondral junction.[6] However this method risked lung and coronary blood vessel damage, cardiac tamponade and arrythmias.[3]

EMB, sampling myocardium, has evolved since it was first pioneered in Japan by S. Sakakibra and S. Konno in 1962.[1] The concept of introducing a biopsy needle through the right internal or external jugular vein to reach the right intraventricular septum for the purpose of sampling the heart muscle was initiated in 1965 by R. T. Bulloch. In 1972, the bioptome and procedure was modified by Philip Caves. This was to allow access percutaneously.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Asher, Alex (July 2017). "A review of endomyocardial biopsy and current practice in England: out of date or underutilised?". The British Journal of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Marini, Davide; Wan, Andrea (2019). "34. Endomyocardial biopsies". In Butera, Gianfranco; Chessa, Massimo; Eicken, Andreas; Thomson, John D. (eds.). Atlas of Cardiac Catheterization for Congenital Heart Disease. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 295–300. ISBN 978-3-319-72442-3. Archived from the original on 2022-01-24. Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- 1 2 3 Melvin, Kenneth R.; Mason, Jay W. (15 June 1982). "Endomyocardial biopsy: its history, techniques and current indications". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 126 (12): 1381–1386. ISSN 0008-4409. PMC 1863164. PMID 7044509.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sandy Watson; Kenneth Gorski (2011). Invasive Cardiology: A Manual for Cath Lab Personnel (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7637-6468-5. Archived from the original on 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- 1 2 From, Aaron M.; Maleszewski, Joseph J.; Rihal, Charanjit S. (November 2011). "Current Status of Endomyocardial Biopsy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (11): 1095–1102. doi:10.4065/mcp.2011.0296. ISSN 0025-6196. PMC 3203000. PMID 22033254.

- 1 2 3 Baim, Donald S. (2006). Grossman's Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, and Intervention (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-7817-5567-2. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ↑ Unterberg-Buchwald, Christina; Ritter, Christian Oliver; Reupke, Verena; Wilke, Robin Niklas; Stadelmann, Christine; Steinmetz, Michael; Schuster, Andreas; Hasenfuß, Gerd; Lotz, Joachim; Uecker, Martin (19 April 2017). "Targeted endomyocardial biopsy guided by real-time cardiovascular magnetic resonance". Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 19: 45. doi:10.1186/s12968-017-0357-3. ISSN 1097-6647. PMID 28424090. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ Hunt, Sharon (19 August 2008). "The Changing Face of Heart Transplantation". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 52 (8): 587–598. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.020. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 18702960.