Epididymitis

| Epididymitis | |

|---|---|

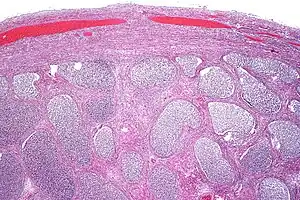

| Other names: Inflammation of the epididymis[1] | |

| |

| Acute epididymitis with abundant fibrinopurulent exudate in the tubules. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Urology, Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Pain in the back of the testicle, swelling of the testicle, burning with urination, frequent urination[1] |

| Complications | Infertility, chronic pain[1] |

| Usual onset | Over a day or two[1] |

| Types | Acute (< 6 weeks), chronic (>12 weeks)[1] |

| Causes | Gonorrhea, chlamydia, enteric bacteria, reflux of urine[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, ultrasound[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, testicular cancer, orchitis[1][2] |

| Treatment | Pain medications, antibiotics, elevation[1] |

| Medication | NSAIDs, ceftriaxone and doxycycline, ofloxacin[1] |

| Frequency | 600,000 per year (age 15-35, US)[2] |

Epididymitis is a medical condition characterized by inflammation of the epididymis, a curved structure at the back of the testicle.[1] Onset of pain is typically over a day or two.[1] The pain may improve with raising the testicle.[1] Other symptoms may include swelling of the testicle, burning with urination, or frequent urination.[1] Inflammation of the testicle is commonly also present.[1]

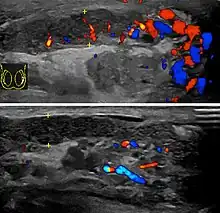

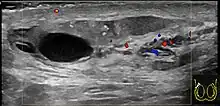

In those who are young and sexually active gonorrhea and chlamydia are frequently the underlying cause.[1] In older males and males who have sex with males enteric bacteria are common.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.[1] Conditions that may result in similar symptoms include testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, and testicular cancer.[1] Ultrasound can be useful if the diagnosis is unclear.[1]

Treatment may include pain medications, NSAIDs, and elevation.[1] Recommended antibiotics in those who are young and sexually active are ceftriaxone and doxycycline.[1] Among those who are older ofloxacin may be used.[1] Complications include infertility and chronic pain.[1] People aged 15 to 35 are most commonly affected with about 600,000 people within this age group affected per year in the United States.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Those ages 15 to 35 are most commonly affected.[2] The acute form usually develops over the course of several days, with pain and swelling frequently in only one testis, which will hang low in the scrotum.[3] There will often be a recent history of dysuria or urethral discharge.[3] Fever is also a common symptom. In the chronic version, the patient may have painful point tenderness but may or may not have an irregular epididymis upon palpation, though palpation may reveal an indurated epididymis. A scrotal ultrasound may reveal problems with the epididymis, but such an ultrasound may also show nothing unusual. The majority of patients who present with chronic epididymitis have had symptoms for over five years.[4]: p.311

Complications

Untreated, acute epididymitis's major complications are abscess formation and testicular infarction. Chronic epididymitis can lead to permanent damage or even destruction of the epididymis and testicle (resulting in infertility and/or hypogonadism), and infection may spread to any other organ or system of the body. Chronic pain is also an associated complication for untreated chronic epididymitis.[5]

Causes

Though urinary tract infections in men are rare, bacterial infection is the most common cause of acute epididymitis.[2] The bacteria in the urethra back-track through the urinary and reproductive structures to the epididymis. In some circumstances, the infection reaches the epididymis [6]

In sexually active men, Chlamydia trachomatis is responsible for many of the acute cases, followed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and E. coli (or other bacteria that cause urinary tract infection). [7][3] Other microbes include Ureaplasma, Mycobacterium, and cytomegalovirus, or Cryptococcus in people with HIV infection.[8] In the majority of cases in which bacteria are the cause, only one side of the scrotum or the other is the locus of pain.[9]

Non-infectious causes are also possible. Reflux of sterile urine (urine without bacteria) through the ejaculatory ducts may cause inflammation with obstruction. In children, it may be a response following an infection with enterovirus, adenovirus or Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Rare non-infectious causes of chronic epididymitis include sarcoidosis (more prevalent in black men) and Behçet's disease.[4]: p.311

Any form of epididymitis can be caused by genito-urinary surgery, including prostatectomy and urinary catheterization. Congestive epididymitis is a long-term complication of vasectomy.[10] Epididymitis may also result from drugs such as amiodarone.[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.[1] Conditions that may result in similar symptoms include testicular torsion, inguinal hernia, and testicular cancer.[1] Ultrasound can be useful if the diagnosis is unclear.[1]

Epididymitis usually has a gradual onset. Typical findings are redness, warmth and swelling of the scrotum, with tenderness behind the testicle, away from the middle (this is the normal position of the epididymis relative to the testicle). The cremasteric reflex (elevation of the testicle in response to stroking the upper inner thigh) remains normal.[1] This is a useful sign to distinguish it from testicular torsion. If there is pain relieved by elevation of the testicle, this is called Prehn's sign[11]

Before the advent of sophisticated medical imaging techniques, surgical exploration was the standard of care. Today, Doppler ultrasound is a common test: it can demonstrate areas of blood flow and can distinguish clearly between epididymitis and torsion. However, as torsion and other sources of testicular pain can often be determined by palpation alone, some studies have suggested that the only real benefit of an ultrasound is to assure the person that they do not have testicular cancer.[12]: p.237 Nuclear testicular blood flow testing may be used.[13]

In sexually active men, tests for sexually transmitted diseases may be done, these may include microscopy and culture of a first void urine sample. Gram stain and culture of fluid or a swab from the urethra, nucleic acid amplification tests (to amplify and detect microbial DNA or other nucleic acids)[7]

Classification

Epididymitis can be classified as acute, subacute, and chronic, depending on the duration of symptoms.[2]

Chronic epididymitis is epididymitis that is present for more than 3 months. Chronic epididymitis is characterized by inflammation even when there is no infection present. Tests are needed to distinguish chronic epididymitis from a range of other disorders that can cause constant scrotal pain including testicular cancer (though this is often painless), enlarged scrotal veins (varicocele), calcifications,[14] and a possible cyst within the epididymis. Some research has found that as much as 80% of visits to a urologist for scrotal pain are for chronic epididymitis.[4]: p.311 As a further complication, the nerves in the scrotal area are closely connected to those of the abdomen, sometimes causing abdominal pain[15]

Chronic epididymitis is most commonly associated with lower back pain, and the onset of pain often co-occurs with activity that stresses the low back (i.e., heavy lifting, long periods of car driving, poor posture while sitting, or any other activity that interferes with the normal curve of the lumbar lordosis region).[12]: p.237

Chronic noninfectious epididymitis

Chronic noninfectious epididymitis – Trauma, autoimmune disease, or vasculitis can cause chronic noninfectious epididymitis, but no clear cause or origin of the disease is found in most cases. Noninfectious epididymitis that happen spontaneously might be caused by the reflux of urine through the ejaculatory ducts and vas deferens into the epididymis, producing inflammation that leads to swelling and ductal obstruction.[16] Men with history of vasectomy are also predisposed to chronic nonifectious epididymitis. Typical inciting factors include prolonged periods of sitting (long plane or car travel, sedentary desk jobs) or vigorous exercise (heavy lifting). Acute infectious epididymitis are often associated with more tenderness and swelling, whereas chronic noninfectious epididymitis tend to have less tenderness and swelling upon examination. Thorough past medical history and physical examination can help with determining the diagnosis. It is often that individuals with chronic noninfectious epididymitis will present with a history of a lack of symptom improvement while on antibiotic therapy. Management of chronic noninfectious epididymitis includes scrotal elevation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (unless unable to take for medical reasons), and it is recommended that individuals avoid physical activities that may cause said symptoms. Those with sedentary jobs or often experience prolonged periods of time sitting should practice physical mobility more frequently.[17]

Chronic infectious epididymitis

Chronic infectious epididymitis is rare.[18] Some signs and symptoms include localized tenderness and swelling in the epididymis, which are different from any tenderness/abnormality present in the testis, these are usually not found in lower urinary tract. Chronic infectious epididymitis may be diagnosed in healthy adolescents as well as men. Some factors that predispose individuals to chronic infectious epididymitis include sexual activity, heavy physical exertion, and bicycle or motorcycle riding.[19] Those diagnosed with chronic or recurrent epididymitis should receive a CT scan with contrast and a prostate ultrasonography to rule out structural abnormality of the urinary tract. If suspected to have chronic infectious epididymitis, consider getting a urinalysis, urine culture, and urine nucleic acid amplification tests for presence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.[16] Management of chronic infectious epididymitis is similar to management of acute infectious epididymitis, rarely does treatment extend to surgical management. [17]

Treatment

In both the acute and chronic forms, antibiotics are used if an infection is suspected, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends doxycycline which may be used for men 14 to 35 years of age for chlamydiae, along with intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone.[1] In chronic epididymitis, a four- to six-week course of antibiotics may be prescribed to ensure the complete eradication of any possible bacterial cause[20]

For cases caused by enteric organisms (such as E. coli), ofloxacin are recommended.[2]

Since bacteria that cause urinary tract infections are often the cause of epididymitis in children, co-trimoxazole can be used.[21]

Household remedies such as elevation of the scrotum and cold compresses applied regularly to the scrotum may relieve the pain in acute cases. Painkillers or anti-inflammatory drugs are often used for treatment of both chronic and acute forms. Hospitalisation is indicated for severe cases, and check-ups can ensure the infection has cleared up. Surgical removal of the epididymis is rarely necessary, causes sterility, and only gives relief from pain in approximately 50% of cases.[5] However, in acute suppurating epididymitis (acute epididymitis with a discharge of pus), an epididymotomy may be recommended[22]; in refractory cases, a full epididymectomy may be required.[22] In cases with unrelenting testicular pain, removal of the entire testicle—orchiectomy—may also be warranted.[23]

It is generally believed that most cases of chronic epididymitis will eventually "burn out" of patient's system if left untreated, though this might take years or even decades.[5]

Epidemiology

Epididymitis makes up 1 in 144 visits for medical care (0.69 percent) in men 18 to 50 years old or 600,000 cases in males between 18 and 35 in the United States.[2]It occurs primarily in those 16 to 30 years of age and 51 to 70 years.[2]

Research

According to a study in 2010, some prostate-related medications have proven effective in treating chronic epididymitis, including doxazosin in combination with Chinese herbal medicine [24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 McConaghy, JR; Panchal, B (1 November 2016). "Epididymitis: An Overview". American Family Physician. 94 (9): 723–726. PMID 27929243.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Trojian, TH; Lishnak, TS; Heiman, D (1 April 2009). "Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview". American Family Physician. 79 (7): 583–7. PMID 19378875.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Jeremy (2008). Oxford American Handbook of Emergency Medicine. New York: Oxford University. p. 992. ISBN 978-0-19-518924-7.

- 1 2 3 Kavoussi, Parviz K.; Costabile, Raymond A. (2011). "Disorders of scrotal contents: orchitis, epididimytis, testicular torsion, torsion of the appendages, and Fournier's gangrene". In Chapple, Christopher R.; Steers, William D. (eds.). Practical urology: essential principles and practice. London: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-84882-033-3.

- 1 2 3 Nickel, J. Curtis; Beiko, Darren T. (2007). "Chapter 23:prostatitis, orchitis, and epididymitis". In Schrier, Robert W. (ed.). Diseases of the kidney and urinary tract. Vol. 1 (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 645. ISBN 978-0-7817-9307-0.

- 1 2 Rupp, Timothy J.; Leslie, Stephen W. (2020). "Epididymitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Epididymitis - 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines". www.cdc.gov. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Williamson, Mary A.; Snyder, L. Michael (2014). Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. Chapter Epididymitis. ISBN 978-1-4698-8741-8. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Marr, Lisa (2007). Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Physician Tells You What You Need to Know. JHU Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-4214-0172-0. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Schwingl PJ, Guess HA (2000). "Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy". Fertil. Steril. 73 (5): 923–36. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.1247. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00482-9. PMID 10785217.

- ↑ "How are physical exam findings for the Prehn sign and cremasteric reflex used to distinguish acute epididymitis from testicular torsion?". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- 1 2 Granitisioti, P. (2008). "Scrotal pain conditions". In Baranowski, Andrew Paul; Abrams, Paul; Fall, Magnus (eds.). Urogenital pain in clinical practice. New York: Informa Healthcare USA. ISBN 978-0849399329.

- ↑ Zitelli, Basil J.; McIntire, Sara C.; Nowalk, Andrew J. (2012). Zitelli and Davis' Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis E-Book: Expert Consult - Online. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 577. ISBN 978-0-323-09158-9. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ Matt A. Morgan and Yuranga Weerakkody. "Epididymal calcification". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 2018-05-21. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ Patel, Abhishek P. (May 2017). "Anatomy and physiology of chronic scrotal pain". Translational Andrology and Urology. 6 (Suppl 1): S51–S56. doi:10.21037/tau.2017.05.32. ISSN 2223-4691. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- 1 2 Trojian, Thomas; Lishnak, Timothy S.; Heiman, Diana L. (2009). "Epididymitis and Orchitis: An Overview". American Family Physician. 79 (7): 583–587. ISSN 0002-838X. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- 1 2 Holcomb, George (1988). "Epididymitis in infants and boys: Underlying urogenital anomalies and efficacy of imaging modalities". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 23 (7): 684. doi:10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80691-2. ISSN 0022-3468. Archived from the original on 2022-02-09. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- ↑ Rupp, Timothy J.; Leslie, Stephen W. (2021), "Epididymitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613565, archived from the original on 2021-08-28, retrieved 2021-08-03

- ↑ "Epididymitis". Cancer Therapy Advisor. 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-08-03. Retrieved 2021-08-03.

- ↑ Mulhall, John P.; Applegarth, Linda D.; Oates, Robert D.; Schlegel, Peter N. (2013). Fertility Preservation in Male Cancer Patients. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-107-01212-7. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Penile and Testicular Disorders. 2008. pp. 658–661. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Epididymitis: Practice Essentials, Anatomy, Etiology". Medscape. 3 November 2020. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Lowe, Gregory (May 2017). "Extirpative surgery for chronic orchialgia: is there a role?". Translational Andrology and Urology. 6 (Suppl 1): S2–S5. doi:10.21037/tau.2017.03.37. ISSN 2223-4691. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ↑ Zhou, Yu-Chun; Xia, Guo-Shou; Xue, Yu-Yang; Zhang, Xin-Dong; Zheng, Lian-Wen; Jin, Bao-Fang (December 2010). "[Kidney-tonifying and dampness-expelling Chinese herbal medicine combined with doxazosin for the treatment of chronic epididymitis]". Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue = National Journal of Andrology. 16 (12): 1143–1146. ISSN 1009-3591. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

Further reading

- Galejs LE (February 1999). "Diagnosis and treatment of the acute scrotum". Am Fam Physician. 59 (4): 817–24. PMID 10068706. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- Nickel JC (2003). "Chronic epididymitis: a practical approach to understanding and managing a difficult urologic enigma". Rev Urol. 5 (4): 209–15. PMC 1553215. PMID 16985840.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Epididymitis at Curlie