Ofloxacin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Floxin, Ocuflox, others |

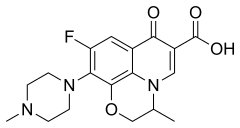

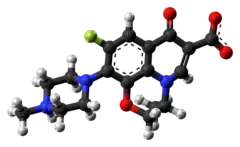

| Other names | (±)-9-fluoro-2,3-dihydro-3-methyl-10-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-7-oxo-7H-pyrido[1,2,3-de][1,4]benzoxazine-6-carboxylic acid |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | by mouth, IV, topical (eye drops and ear drops) |

| Defined daily dose | 0.4 gram (by mouth) 0.4 gram (parenteral)[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Systemic: Monograph Eye and ear: Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691005 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 85% – 95% |

| Protein binding | 32% |

| Elimination half-life | 8–9 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H20FN3O4 |

| Molar mass | 361.373 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 250–257 °C (482–495 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Ofloxacin is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[2] When taken by mouth or injection into a vein, these include pneumonia, cellulitis, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, plague, and certain types of infectious diarrhea.[2][3] Other uses, along with other medications, include treating multidrug resistant tuberculosis.[4] An eye drop may be used for a superficial bacterial infection of the eye and an ear drop may be used for otitis media when a hole in the ear drum is present.[3]

When taken by mouth, common side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and rash.[2] Other serious side effect include tendon rupture, numbness due to nerve damage, seizures, and psychosis.[2] Use in pregnancy is typically not recommended.[5] Ofloxacin is in the fluoroquinolone family of medications.[2] It works by interfering with the bacterium's DNA.[2]

Ofloxacin was patented in 1980 and approved for medical use in 1985.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$3.27 per month.[8] In the United States, a course of treatment costs about $50–100.[9] In 2017, it was the 278th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

Ofloxacin is used in the treatment of bacterial infections such as:

- Acute bacterial exacerbations of COPD

- Community-acquired pneumonia

- Uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections

- Nongonococcal urethritis and cervicitis

- Epididymitis

- Mixed Infections of the urethra and cervix

- Acute pelvic inflammatory disease

- Uncomplicated cystitis

- Complicated urinary tract infections

- Prostatitis

- Acute, uncomplicated urethral and cervical gonorrhea

Ofloxacin has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of syphilis.[12] Ofloxacin is no longer considered a first-line treatment for gonorrhea, because of bacterial resistance.[13][14][15]

Susceptible bacteria

According to the product package insert, ofloxacin is effective against these microorganisms:[16]

Aerobic Gram-positive microorganisms:

- Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-susceptible strains)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (penicillin-susceptible strains)

- Streptococcus pyogenes

Aerobic Gram-negative microorganisms

- Citrobacter koseri (Citrobacter diversus)

- Enterobacter aerogenes

- Escherichia coli

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Proteus mirabilis

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Other microorganisms:

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 0.4 gram by mouth or parenteral[1]

Side effects

In general, fluoroquinolones are well tolerated, with most side effects being mild to moderate.[17] On occasion, serious adverse effects occur.[18] Common side effects include gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as headache and insomnia.

The overall rate of adverse events in patients treated with fluoroquinolones is roughly similar to that seen in patients treated with other antibiotic classes.[19][20][21][22] A U.S. Centers for Disease Control study found patients treated with fluoroquinolones experienced adverse events severe enough to lead to an emergency department visit more frequently than those treated with cephalosporins or macrolides, but less frequently than those treated with penicillins, clindamycin, sulfonamides, or vancomycin.[23]

Postmarketing surveillance has revealed a variety of relatively rare but serious adverse effects associated with all members of the fluoroquinolone antibacterial class. Among these, tendon problems and exacerbation of the symptoms of the neurological disorder myasthenia gravis are the subject of "black box" warnings in the United States. The most severe form of tendonopathy associated with fluoroquinolone administration is tendon rupture, which in the great majority of cases involves the Achilles tendon. Younger people typically experience good recovery, but permanent disability is possible, and is more likely in older patients.[24] The overall frequency of fluoroquinolone-associated Achilles tendon rupture in patients treated with ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin has been estimated at 17 per 100,000 treatments.[25][26] Risk is substantially elevated in the elderly and in those with recent exposure to topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy. Simultaneous use of corticosteroids is present in almost one-third of quinolone-associated tendon rupture.[27] Tendon damage may manifest during and up to a year after fluoroquinolone therapy has been completed.[28]

Fluoroquinolones prolong the QT interval by blocking voltage-gated potassium channels.[29] Prolongation of the QT interval can lead to torsades de pointes, a life-threatening arrhythmia, but in practice, this appears relatively uncommon in part because the most widely prescribed fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) only minimally prolong the QT interval.[30]

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea may occur in connection with the use of any antibacterial drug, especially those with a broad spectrum of activity such as clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinoline treatment is associated with risk similar to[31] or less [32][33] than that associated with broad spectrum cephalosporins. Fluoroquinoline administration may be associated with the acquisition and outgrowth of a particularly virulent Clostridium strain.[34]

The U.S. prescribing information contains a warning regarding uncommon cases of peripheral neuropathy, which can be permanent.[35] Other nervous system effects include insomnia, restlessness, and rarely, seizure, convulsions, and psychosis[36] Other rare and serious adverse events have been observed with varying degrees of evidence for causation.[37][38][39][40]

Events that may occur in acute overdose are rare, and include kidney failure and seizure.[41] Susceptible groups of patients, such as children and the elderly, are at greater risk of adverse reactions during therapeutic use.[17][42][43]

Ofloxacin, like some other fluoroquinolones, may inhibit drug-metabolizing enzymes, and thereby increase blood levels of other drugs such as cyclosporine, theophylline, and warfarin, among others. These increased blood levels may result in a greater risk of side effects.

Careful monitoring of serum glucose is advised when ofloxacin or other fluorquinolones are used by people who are taking sulfonylurea antidiabetes drugs.

The concomitant administration of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug with a quinolone, including ofloxacin, may increase the risk of central nervous system stimulation and convulsive seizures.

The fluoroquinolones have been shown to increase the anticoagulant effect of acenocoumarol, anisindione, and dicumarol. Additionally, the risk of cardiotoxicity and arrhythmias is increased when co-administered with drugs such as dihydroquinidine barbiturate, quinidine, and quinidine barbiturate.[44]

Current or past treatment with oral corticosteroids is associated with an increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture, especially in elderly patients who are also taking the fluoroquinolones.[45]

Contraindications

As noted above, under licensed use, ofloxacin is now considered to be contraindicated for the treatment of certain sexually transmitted diseases by some experts due to bacterial resistance.[13] Caution should be used in people with liver disease.[46] The excretion of ofloxacin may be reduced in patients with severe liver function disorders (e.g., cirrhosis with or without ascites). Ofloxacin is also considered to be contraindicated within the pediatric population, pregnancy, nursing mothers, patients with psychiatric illnesses and in patients with epilepsy or other seizure disorders.

Pregnancy

Ofloxacin has not been shown to have any teratogenic effects at oral doses as high as 810 mg/kg/day (11 times the recommended maximum human dose based on mg/m2 or 50 times based on mg/kg) and 160 mg/kg/day (four times the recommended maximum human dose based on mg/m2 or 10 times based on mg/kg) when administered to pregnant rats and rabbits, respectively. Additional studies in rats with oral doses up to 360 mg/kg/day (five times the recommended maximum human dose based on mg/m2 or 23 times based on mg/kg) demonstrated no adverse effect on late fetal development, labor, delivery, lactation, neonatal viability, or growth of the newborn. Doses equivalent to 50 and 10 times the recommended maximum human dose of ofloxacin (based on mg/kg) were fetotoxic (i.e., decreased fetal body weight and increased fetal mortality) in rats and rabbits, respectively. Minor skeletal variations were reported in rats receiving doses of 810 mg/kg/day, which is more than 10 times higher than the recommended maximum human dose based on mg/m2. There are, however, no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Ofloxacin should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.[12]

Children

Oral and intravenous ofloxacin are not licensed for use in children, except as noted above, due to the risk of musculoskeletal injury. In one study,[49][50] 1534 juvenile patients (age 6 months to 16 years) treated with levofloxacin as part of three efficacy trials were followed up to assess all musculoskeletal events occurring up to 12 months after treatment. At 12 months' follow-up, the cumulative incidence of musculoskeletal adverse events was 3.4%, compared to 1.8% among 893 patients treated with other antibiotics. In the levafloxacin-treated group, about two-thirds of these musculoskeletal adverse events occurred in the first 60 days, 86% were mild, 17% were moderate, and all resolved without long-term sequelae.

In a study comparing the safety and efficacy of levofloxacin to that of azithromycin or ceftriaxone in 712 children with community-acquired pneumonia, adverse events were experienced by 6% of those treated with levofloxacin and 4% of those treated with comparator antibiotics. Most of these adverse events were thought to be unrelated or doubtfully related to the levofloxacin. Two deaths were observed in the levofloxacin group, neither of which was thought to be treatment-related. Spontaneous reports to the FDA Adverse Effects Reporting System at the time of the 20 September 2011 FDA Pediatric Drugs Advisory Committee include musculoskeletal events (39, including five cases of tendon rupture) and central nervous system events (19, including five cases of seizures) as the most common spontaneous reports between April 2005 and March 2008. An estimated 130,000 pediatric prescriptions for levofloxacin were filled on behalf of 112,000 pediatric patients during that period.[51]

Overdose

Limited information is available on overdose with ofloxacin. Advice for the management of an acute overdose of ofloxacin is emptying of the stomach, along with close observation, and making sure that the patient is appropriately hydrated. Hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis is of only limited effectiveness.[12] Overdose may result in central nervous system toxicity, cardiovascular toxicity, tendon/articular toxicity, and liver toxicity[41] as well as kidney failure and seizure.[41] Both seizures and severe psychiatric reactions have, however, been reported to occur at therapeutic dosage.[52][53][54]

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of ofloxacin in the tablet form is roughly 98% following oral administration, reaching maximum serum concentrations within one to two hours. Between 65% and 80% of an administered oral dose of ofloxacin is excreted unchanged via the kidneys within 48 hours of dosing. Therefore, elimination is mainly by renal excretion. However, 4-8% of an ofloxacin dose is excreted in the feces. This would indicate a small degree of biliary excretion, as well. Plasma elimination half-life is around 4 to 5 hours in patients and 6.4 to 7.4 hours in elderly patients.[12]

Ofloxacin is a racemic mixture, which consists of 50% levofloxacin (the biologically active component) and 50% of its “mirror image” or enantiomer dextrofloxacin.[55]

"After multiple-dose administration of 200 mg and 300 mg doses, peak serum levels of 2.2 and 3.6 μg/ml, respectively, are predicted at steady-state. In vitro, approximately 32% of the drug in plasma is protein bound. Floxin is widely distributed to body tissues. Ofloxacin has been detected in blister fluid, cervix, lung tissue, ovary, prostatic fluid, prostatic tissue, skin, and sputum. Pyridobenzoxazine ring appears to decrease the extent of parent compound metabolism. Less than 5% is eliminated by the kidneys as desmethyl or N-oxide metabolites; 4% to 8% by feces."[12][56]

A number of the endogenous compounds have been reported to be affected by ofloxacin as inhibitors, alteraters, and depletors. See the latest package insert for ofloxacin for additional details.[12]

Mode of action

Ofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It functions by inhibiting two bacterial type II topoisomerases, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV.[57] Topo IV is an enzyme necessary to separate (mostly in prokaryotes, in bacteria in particular) replicated DNA, thereby inhibiting bacterial cell division.

History

Ofloxacin is a second-generation fluoroquinolone, being a broader-spectrum analog of norfloxacin, and was synthesized and developed by scientists at Daiichi Seiyaku.[58][59]

It was first approved for marketing in Japan in 1985, for oral administration, and Daiichi marketed it there under the brand name Tarvid.[60] Daiichi, working with Johnson & Johnson, obtained FDA approval in December 1990, under the brand name Floxin, labelled for use in adults with lower respiratory tract infections, skin and skin structure infections, urinary tract infections, prostatitis, and sexually transmitted diseases.[61][62] By 1991, it was also marketed as Tarvid by Hoechst in the UK, Germany, Belgium, and Portugal; as Oflocet in France, Portugal, Tunisia, and several African countries by Roussel-Uclafas, as Oflocin by Glaxo in Italy, and as Flobacin by Sigma-Tau in Italy.[59]

The market for ofloxacin was seen as difficult from its launch; it was approved as a "1C" drug, a new molecular entity with little or no therapeutic gain over existing therapies, and ciprofloxacin, which had a broader spectrum, was already on the market.[62]

By 1992, an intravenous solution was approved for marketing,[63]

In 1997, an indication for pelvic inflammatory disease was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the oral formulation,[64] and in the same year, a solution for ear infections was approved under the brand [65]

Daiichi and J&J also cannibalized its own market by introducing levofloxacin, the levo-enantiomer of ofloxacin, in 1996;[60] Johnson and Johnson's annual sales of Floxin in 2003 was about $30 million, whereas their combined sales of Levaquin/Floxin exceeded $1.15 billion in the same year.[66][67] Johnson & Johnson withdrew the marketing application in 2009.[68]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$3.27 per month.[8] In the United States, a course of treatment costs about $50–100.[9] In 2017, it was the 278th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[10][11]

.svg.png.webp) Ofloxacin costs (US)

Ofloxacin costs (US).svg.png.webp) Ofloxacin prescriptions (US)

Ofloxacin prescriptions (US)

Available forms

Ofloxacin for systemic use is available as a tablet (multiple strengths), an oral solution (250 mg/ml), and an injectable solution (multiple strengths). It is also used as eye drops and ear drops and is available in combination with ornidazole.

Dosage

The kidney and liver function should be taken into consideration to avoid an accumulation that may lead to a fatal drug overdose. Ofloxacin is eliminated primarily by the kidneys. However, the drug is also metabolized and partially cleared through the liver. Modification of the dosage is' required using the table found within the package insert for those with impaired liver or kidney function (particularly for patients with severe renal dysfunction). However, since the drug is known to be substantially excreted by the kidneys, the risk of toxic reactions to this drug may be greater in patients with impaired renal function. The duration of treatment depends upon the severity of infection and the usual duration is 7 to 14 days.[12]

Resistance

Resistance to ofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones may evolve rapidly, even during a course of treatment. Numerous pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, enterococci, and Streptococcus pyogenes now exhibit resistance worldwide.[69]

Floxacin and other fluoroquinolones had become the most commonly prescribed class of antibiotics to adults in 2002. Nearly half (42%) of these prescriptions were for conditions not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), such as acute bronchitis, otitis media, and acute upper respiratory tract infection, according to a study that was supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[70][71] Additionally they are commonly prescribed for medical conditions that are not even bacterial to begin with, such as viral infections, or those to which no proven benefit exists.

References

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Ofloxacin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 409, 757, 782. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 140. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ "Ofloxacin Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 500. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 1 2 "Ofloxacin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 101. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Ofloxacin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Ofloxacin tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 4 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- 1 2 Susan Blank; Julia Schillinger (May 14, 2004). "DOHMH ALERT #8:Fluoroquinolone-resistant gonorrhea, NYC". USA: New York County Medical Society. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ↑ Knapp JS, Fox KK, Trees DL, Whittington WL (1997). "Fluoroquinolone resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae". Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3 (1): 33–9. doi:10.3201/eid0301.970104. PMC 2627594. PMID 9126442.

- ↑ Dan M (April 2004). "The use of fluoroquinolones in gonorrhoea: the increasing problem of resistance". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 5 (4): 829–54. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.4.829. PMID 15102567.

- ↑ Sato K, Matsuura Y, Inoue M, Une T, Osada Y, Ogawa H, Mitsuhashi S (October 1982). "In vitro and in vivo activity of DL-8280, a new oxazine derivative". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22 (4): 548–53. doi:10.1128/aac.22.4.548. PMC 183791. PMID 6960805.

- 1 2 Owens RC, Ambrose PG (July 2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881. Archived from the original on 2019-08-03. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ↑ De Sarro A, De Sarro G (March 2001). "Adverse reactions to fluoroquinolones. an overview on mechanistic aspects". Curr. Med. Chem. 8 (4): 371–84. doi:10.2174/0929867013373435. PMID 11172695.

- ↑ "Data Mining Analysis of Multiple Antibiotics in AERS". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 2016-03-10.

- ↑ Skalsky K, Yahav D, Lador A, Eliakim-Raz N, Leibovici L, Paul M (April 2013). "Macrolides vs. quinolones for community-acquired pneumonia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19 (4): 370–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03838.x. PMID 22489673.

- ↑ Falagas ME, Matthaiou DK, Vardakas KZ (December 2006). "Fluoroquinolones vs beta-lactams for empirical treatment of immunocompetent patients with skin and soft tissue infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Mayo Clin. Proc. 81 (12): 1553–66. doi:10.4065/81.12.1553. PMID 17165634.

- ↑ Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM (2009). "Safety profile of the respiratory fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin: comparison with other fluoroquinolones and other antibacterial classes". Drug Saf. 32 (5): 359–78. doi:10.2165/00002018-200932050-00001. PMID 19419232.

- ↑ Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS (September 2008). "Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events". Clin. Infect. Dis. 47 (6): 735–43. doi:10.1086/591126. PMID 18694344.

- ↑ Kim GK (April 2010). "The Risk of Fluoroquinolone-induced Tendinopathy and Tendon Rupture: What Does The Clinician Need To Know?". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 3 (4): 49–54. PMC 2921747. PMID 20725547.

- ↑ Sode J, Obel N, Hallas J, Lassen A (May 2007). "Use of fluroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (5): 499–503. doi:10.1007/s00228-007-0265-9. PMID 17334751.

- ↑ Owens RC, Ambrose PG (July 2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881.

- ↑ Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG (October 2005). "Musculoskeletal injury associated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics". Clin Plast Surg. 32 (4): 495–502, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2005.05.004. PMID 16139623.

- ↑ Saint F, Gueguen G, Biserte J, Fontaine C, Mazeman E (September 2000). "[Rupture of the patellar ligament one month after treatment with fluoroquinolone]". Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar mot (in French). 86 (5): 495–7. PMID 10970974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Heidelbaugh JJ, Holmstrom H (April 2013). "The perils of prescribing fluoroquinolones". J Fam Pract. 62 (4): 191–7. PMID 23570031.

- ↑ Rubinstein E, Camm J (April 2002). "Cardiotoxicity of fluoroquinolones". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49 (4): 593–6. doi:10.1093/jac/49.4.593. PMID 11909831.

- ↑ Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. (September 2013). "Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 (9): 1951–61. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt129. PMID 23620467.

- ↑ Slimings C, Riley TV (December 2013). "Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69 (4): 881–91. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt477. PMID 24324224.

- ↑ "Data Mining Analysis of Multiple Antibiotics in AERS". Archived from the original on 2016-03-10.

- ↑ Vardakas KZ, Konstantelias AA, Loizidis G, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME (November 2012). "Risk factors for development of Clostridium difficile infection due to BI/NAP1/027 strain: a meta-analysis". Int. J. Infect. Dis. 16 (11): e768–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.07.010. PMID 22921930.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label changes to warn of risk for possibly permanent nerve damage from antibacterial fluoroquinolone drugs taken by mouth or by injection". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 2016-05-28.

- ↑ Galatti L, Giustini SE, Sessa A, et al. (March 2005). "Neuropsychiatric reactions to drugs: an analysis of spontaneous reports from general practitioners in Italy". Pharmacol. Res. 51 (3): 211–6. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2004.08.003. PMID 15661570.

- ↑ Babar, S. (October 2013). "SIADH Associated With Ciprofloxacin". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (10): 1359–1363. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 24259701.

- ↑ Rouveix, B. (Nov–Dec 2006). "[Clinically significant toxicity and tolerance of the main antibiotics used in lower respiratory tract infections]". Med Mal Infect. 36 (11–12): 697–705. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2006.05.012. PMID 16876974.

- ↑ Mehlhorn AJ, Brown DA (November 2007). "Safety concerns with fluoroquinolones". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 41 (11): 1859–66. doi:10.1345/aph.1K347. PMID 17911203.

- ↑ Jones SF, Smith RH (March 1997). "Quinolones may induce hepatitis". BMJ. 314 (7084): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7084.869. PMC 2126221. PMID 9093098.

- 1 2 3 Nelson, Lewis H.; Flomenbaum, Neal; Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Hoffman, Robert Louis; Howland, Mary Deems; Neal A. Lewin (2006). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 978-0-07-143763-9. Archived from the original on 2014-06-12.

- ↑ Iannini PB (June 2007). "The safety profile of moxifloxacin and other fluoroquinolones in special patient populations". Curr Med Res Opin. 23 (6): 1403–13. doi:10.1185/030079907X188099. PMID 17559736.

- ↑ Farinas, Evelyn R; PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH (1 March 2005). "Consult: One-Year Post Pediatric Exclusivity Postmarketing Adverse Events Review" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ↑ "Showing drug card for Ofloxacin (DB01165)". Canada: DrugBank. February 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016.

- ↑ van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM, Leufkens HM, Rowlands S, Stricker BH (August 2003). "Increased risk of achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (15): 1801–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.15.1801. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 12912715.

- ↑ Coban S, Ceydilek B, Ekiz F, Erden E, Soykan I (October 2005). "Levofloxacin-induced acute fulminant hepatic failure in a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection". Ann Pharmacother. 39 (10): 1737–40. doi:10.1345/aph.1G111. PMID 16105873.

- ↑ Pharmacotherapy: Official Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Print ISSN 0277-0008 Volume: 25 | Issue: 1 Cover date: January 2005 Page(s): 116–118

- ↑ Nardiello, S; Pizzella, T; Ariviello, R (March 2002). "Risks of antibacterial agents in pregnancy". Le Infezioni in Medicina : Rivista Periodica di Eziologia, Epidemiologia, Diagnostica, Clinica e Terapia delle Patologie Infettive. 10 (1): 8–15. PMID 12700435.

- ↑ "Levaquin- levofloxacin tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 12 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ↑ Noel GJ, Bradley JS, Kauffman RE (October 2007). "Comparative safety profile of levofloxacin in 2523 children with a focus on four specific musculoskeletal disorders". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (10): 879–91. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd382. PMID 17901792.

- ↑ (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) https://web.archive.org/web/20160307233555/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/slides/2008-4399s1-06%20(Levofloxacin).pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Hall, CE; Keegan, H; Rogstad, KE (September 2003). "Psychiatric side effects of ofloxacin used in the treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease". Int J STD AIDS. 14 (9): 636–7. doi:10.1258/095646203322301121. PMID 14511503.

- ↑ Amsden, GW; Graci, DM; Cabelus, LJ; Hejmanowski, LG (July 1999). "A randomized, crossover design study of the pharmacology of extended-spectrum fluoroquinolones for pneumococcal infections" (PDF). Chest. 116 (1): 115–9. doi:10.1378/chest.116.1.115. PMID 10424513.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Drugs.com. "Complete Ofloxacin information from Drugs.com". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ↑ Drlica K, Zhao X (1 September 1997). "DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 61 (3): 377–92. doi:10.1128/.61.3.377-392.1997. PMC 232616. PMID 9293187. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ↑ Walter Sneader (31 October 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- 1 2 Mouton Y, Leroy O (1991). "Ofloxacin". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 1 (2–3): 57–74. doi:10.1016/0924-8579(91)90001-T. PMID 18611493.

- 1 2 S Atarashi from Daiichi. Research and Development of Quinolones in Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed August 25, 2016

- ↑ Staff, Fish and Richardson. memorANDA, Q2, 2009 Archived 2016-08-27 at the Wayback Machine p. VIII. Cites US Patent 4,382,892 Archived 2016-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Staff, The Pink Sheet. Jan 7, 1991 Johnson & Johnson Going Into 1991 With At Least Four New Product Launches: Floxin, Vascor, Procrit And Duragesic; J&J Leading Off With Procrit, Vascor Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Flor, SC; Rogge, MC; Chow, AT (July 1993). "Bioequivalence of oral and intravenous ofloxacin after multiple-dose administration to healthy male volunteers". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 37 (7): 1468–72. doi:10.1128/aac.37.7.1468. PMC 187996. PMID 8363378.

- ↑ "Floxin Tablets (ofloxacin tablets)". Centerwatch. Floxin Tablets New FDA Drug Approval | CenterWatch. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Floxin otic New FDA Drug Approval". Centerwatch. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27.

- ↑ Business Wire (September 2, 2003). "Teva Announces Approval of Ofloxacin Tablets, 200 mg, 300 mg, and 400 mg". Business Wire. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ↑ Johnson & Johnson (2003). "Building on a foundation of health" (PDF). Shareholder. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ↑ "Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. et al.; Withdrawal of Approval of 92 New Drug Applications and 49 Abbreviated New Drug Applications". Federal Register 74(95):23407-23412. May 19, 2009. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016.

see also FDA docket number FDA-2009-N-0211

- ↑ M Jacobs, Worldwide Overview of Antimicrobial Resistance. International Symposium on Antimicrobial Agents and Resistance 2005.

- ↑ Linder JA, Huang ES, Steinman MA, Gonzales R, Stafford RS (March 2005). "Fluoroquinolone prescribing in the United States: 1995 to 2002". Am. J. Med. 118 (3): 259–68. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.015. PMID 15745724.

- ↑ K08 HS14563 and HS11313

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |