Prontosil

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sulfamidochrysoïdine, Rubiazol, Prontosil rubrum, Aseptil rojo, Streptocide, Sulfamidochrysoïdine hydrochloride |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.802 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

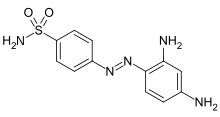

| Formula | C12H13N5O2S |

| Molar mass | 291.33 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Prontosil is an antibacterial drug of the sulfonamide group. It has a relatively broad effect against gram-positive cocci but not against enterobacteria. One of the earliest antimicrobial drugs, it was widely used in the mid-20th century but is little used today because better options now exist. The discovery and development of this first sulfonamide drug opened a new era in medicine,[1] because it greatly widened the success of antimicrobial chemotherapy in an era when many physicians doubted its still largely untapped potential. At the time, disinfectant cleaners and topical antiseptic wound care were widely used but there were very few antimicrobial drugs to use safely inside living bodies. Antibiotic drugs derived from microbes, which we rely on heavily today, did not yet exist. Prontosil was discovered in 1932[2] by a research team at the Bayer Laboratories of the IG Farben conglomerate in Germany.

Names

The capitalized name "Prontosil" is Bayer's trade name; the nonproprietary names include sulfamidochrysoïdine, rubiazol, prontosil rubrum, prontosil flavum, aseptil rojo, streptocide, and sulfamidochrysoïdine hydrochloride. Because the drug predates the modern system of drug nomenclature, which ensures that nonproprietary names are well known from the inception of marketing, it was generally known among the public only by its trade name, and the trade name was the origin of some of the nonproprietary names (as also happened with "aspirin").

History

This compound was first synthesized by Bayer chemists Josef Klarer and Fritz Mietzsch as part of a research program designed to find dyes that might act as antibacterial drugs in the body. The molecule was tested and in the late autumn of 1932 was found effective against some important bacterial infections in mice by Gerhard Domagk, who subsequently received the 1939 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Prontosil was the result of five years of testing involving thousands of compounds related to azo dyes.

The crucial test result (in a murine model of Streptococcus pyogenes systemic infection) that preliminarily established the antibacterial efficacy of Prontosil in mice dates from late December 1931. IG Farben filed a German patent application concerning its medical utility on December 25, 1932.[3] The synthesis of the compound had been first reported by Paul Gelmo, a chemistry student working at the University of Vienna in his 1909 thesis, although he had not realized its medical potential.

The readily water-soluble sodium salt of sulfonamidochrysoidine, which gives a burgundy red solution and was trademarked Prontosil Solubile, was clinically investigated between 1932 and 1934, first at the nearby hospital at Wuppertal-Elberfeld headed by Philipp Klee, and then at the Düsseldorf University Hospital. The results were published in a series of articles in the February 15, 1935 issue of Germany's then pre-eminent medical scientific journal, Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift,[4] and were initially received with some skepticism by a medical community bent on vaccination and crude immunotherapy.

Leonard Colebrook introduced it as a cure for puerperal fever.[5] As impressive clinical successes with Prontosil started to be reported from all over Europe, and especially after a widely published treatment in 1936[6] of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr.[7] (a son of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt), acceptance was quick and dozens of medicinal chemistry teams set out to improve Prontosil.

Eclipse and legacy

In late 1935, working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris in the laboratory of Dr. Ernest Fourneau, Jacques and Thérèse Tréfouël, Dr. Daniel Bovet and Federico Nitti discovered that Prontosil is metabolized to sulfanilamide (para-aminobenzenesulfonamide), a much simpler, colorless molecule, reclassifying Prontosil as a prodrug.[8] Prontalbin became the first oral version of sulfanilamide by Bayer, which had actually obtained a German patent on sulfanilamide as early as 1909, without realizing its medical potential at this time.[9]

It has been argued that IG Farben might have made its breakthrough discovery with sulfanilamide in 1932 but, recognizing that it would not be patentable as an antibacterial, had spent the next three years developing Prontosil as a new, and therefore more easily patentable, compound.[10] However Dr. Bovet, who has received a Nobel Prize for medicine, and one of the authors of the French discovery, wrote in 1988: "Today, we have the proof that the chemists of Elberfeld were unaware of the properties of sulfanilamide at the time of our discovery and that it was by our communication that they were informed. To be convinced about it, it is enough to attentively examine the monthly reports of work of Mietzsch and Klarer during years 1935–1936 and especially the Log Book of Gerhard Domagk: the formula of sulphamide is consigned there – without comment – not before January 1936."[11]

Dr. Alexander Ashley Weech (1895–1977), a pioneer pediatrician, while working at Columbia University's College of Physicians & Surgeons (in the affiliated New York Babies Hospital) treated the first patient in the United States with an antibiotic (sulfanilamide; prontosil) in 1935 which led to a new era of medicine across the Atlantic.[12] Dr. Weech researched Domagk's work,[4] translating the German article,[13] and "was so intrigued by [the] experiments and by the three accompanying clinical articles on Prontosil that he contacted a pharmaceutical house, obtained a supply of the drug, and proceeded to treat a patient [a daughter of a colleague[14]] who had serious streptococcal disease."[15] Dr. Perrin Long and Dr. Eleanor Bliss of Johns Hopkins University began their pioneering work later on prontosil and sulfanilamide which led to the large scale production of this new treatment saving the lives of millions with systemic bacterial infections.[12][16]

Sulfanilamide was cheap to produce and (due to the early date of its original composition of matter patent which made no reference to a medical use) was already off-patent when its antibacterial properties were first made public. Since the sulfanilamide moiety was also easy to link into other molecules, chemists soon gave rise to hundreds of second-generation sulfonamide drugs. As a result, Prontosil failed to make the profits in the marketplace hoped for by Bayer. Although quickly eclipsed by these newer "sulfa drugs" and, in the mid-1940s and through the 1950s by penicillin and other antibacterials that proved more effective against more types of bacteria, Prontosil remained on the market until the 1960s. Prontosil's discovery ushered in the era of antibacterial drugs and had a profound effect on pharmaceutical research, drug laws, and medical history.

Sulfonamide-trimethoprim combinations (co-trimoxazole) are still used extensively against opportunistic infections in patients with AIDS, urinary infections and in the treatment of burns. However, in many other situations, sulfa drugs have been replaced by beta-lactam antibacterials.

References

- ↑ Hager T (2006). The Demon Under the Microscope: From Battlefield Hospitals to Nazi Labs, One Doctor's Heroic Search for the World's First Miracle Drug. Harmony Books. ISBN 1-4000-8214-5.

- ↑ Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. OUP Oxford. 2009. p. 56. ISBN 9780191039621.

- ↑ Lesch JE (2007). "Chapter 3: Prontosil". The first miracle drugs: how the sulfa drugs transformed medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-518775-5.

- 1 2 Domagk G (15 February 1935). "Ein Beitrag zur Chemotherapie der bakteriellen Infektionen". Deutsch. Med. WSCHR. 61 (7): 250. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1129486.

- ↑ Dunn PM (May 2008). "Dr Leonard Colebrook, FRS (1883-1967) and the chemotherapeutic conquest of puerperal infection". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 93 (3): F246-8. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.104448. PMID 18426926. S2CID 19923455.

- ↑ Rubin RP (December 2007). "A brief history of great discoveries in pharmacology: in celebration of the centennial anniversary of the founding of the American Society of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics". Pharmacological Reviews. 59 (4): 289–359. doi:10.1124/pr.107.70102. PMID 18160700. S2CID 33152970.

- ↑ "Medicine: Prontosil". TIME Magazine. December 28, 1936. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008.

- ↑ Tréfouël JT, Nitti F, Bovet D (23 November 1935). "Activité du p-aminophénylsulfamide sur l'infection streptococcique expérimentale de la souris et du lapin". C. R. Soc. Biol. 120: 756.

- ↑ Hörlein H (May 18, 1909), Deutsches Reich Patentschrift Nr. 226239

- ↑ Comroe JH (December 1976). "Retrospectroscope: Missed opportunities". The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 114 (6): 1167–74. doi:10.1164/arrd.1976.114.6.1167 (inactive 31 October 2021). PMID 795333.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ↑ Bovet D (1988). "Une chimie qui guérit. Histoire de la découverte des sulfamides". Payot, Coll. Médecine et Sociétés. Paris: 132.

Nous possédons aujourd'hui la preuve qu'au moment de notre découverte les chimistes d'Elberfeld [...] ignoraient complètement [les propriétés] du sulfamide et que ce fut par notre communication qu'ils en furent informés. Il suffit, pour s'en convaincre, d'examiner attentivement les rapports mensuels de travail de Mietzsch et Klarer au cours des années 1935–1936 et surtout le Journal de bord de G. Domagk : la formule du sulfamide n'y est consignée – sans commentaire – qu'en janvier 1936.

- 1 2 Chandler CA (1950). Famous Men of Medicine. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

- ↑ Weech AA (1970). "The guilding lamp of history". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 119 (3): 199. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1970.02100050201001.

- ↑ Shulman ST (2004). "A history of pediatric specialties". Pediatr Res. 55 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1203/01.PDR.0000101756.93542.09. PMC 7086672. PMID 14605240.

- ↑ Forbes GB (December 1972). "A. Ashley Weech, MD". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 124 (6): 818–9. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1972.02110180020002. PMID 4565222.

- ↑ "Interesting Facts About Antibiotics". emedexpert.com. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Further reading

Lesch JE (2007). The First Miracle Drugs: How the Sulfa Drugs Transformed Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195187755. Retrieved 29 December 2017.