Erdheim–Chester disease

| Erdheim–Chester disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Erdheim–Chester syndrome or Polyostotic sclerosing histiocytosis | |

| |

| Chester-Erdheim disease | |

Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) is an extremely rare disease characterized by the abnormal multiplication of a specific type of white blood cells called histiocytes, or tissue macrophages (technically, this disease is termed a non-Langerhans-cell histiocytosis). It was declared a histiocytic neoplasm by the World Health Organization in 2016.[1] Onset typically is in middle age. The disease involves an infiltration of lipid-laden macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the bone marrow, and a generalized sclerosis of the long bones.[2]

Signs and symptoms

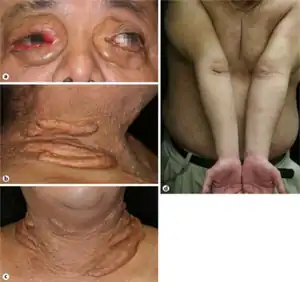

Long bone involvement is almost universal in ECD patients and is bilateral and symmetrical in nature. More than 50% of cases have some sort of extraskeletal involvement. This can include kidney, skin, brain and lung involvement, and less frequently retroorbital tissue, pituitary gland and heart involvement is observed.[3]

Bone pain is the most frequent of all symptoms associated with ECD and mainly affects the lower limbs, knees and ankles. The pain is often described as mild but permanent, and in tissues near an articulation, or joint in nature. Exophthalmos occurs in some patients and is usually bilateral, symmetric and painless, and in most cases it occurs several years before the final diagnosis. Recurrent pericardial effusion can be a manifestation,[4] as can morphological changes in adrenal size and infiltration.[5]

A review of 59 case studies by Veyssier-Belot et al. in 1996 reported the following symptoms in order of frequency of occurrence:[6]

- Bone pain

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

- Diabetes insipidus

- Exophthalmos

- Xanthomas

- Neurological signs (including ataxia)

- Dyspnea caused by interlobular septal and pleural thickening.

- Kidney failure

- Hypopituitarism

- Liver failure

Cause

The cause of this condition is yet not known, however it is suspected that it is either a reactive or neoplastic disorder (many affected individuals have mutations in the BRAF proto-oncogene)[7]

Diagnosis

Radiologic osteosclerosis and histology are the main diagnostic features. Diagnosis can often be difficult because of the rareness of ECD as well as the need to differentiate it from LCH. A diagnosis from neurological imaging may not be definitive. The presence of symmetrical cerebellar and pontine signal changes on T2-weighted images seem to be typical of ECD, however, multiple sclerosis and metabolic diseases must also be considered in the differential diagnosis.[8] ECD is not a common cause of exophthalmos but can be diagnosed by biopsy. However, like all biopsies, this may be inconclusive.[9] Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery may be used for diagnostic confirmation and also for therapeutic relief of recurrent pericardial fluid drainage.[10]

Histology

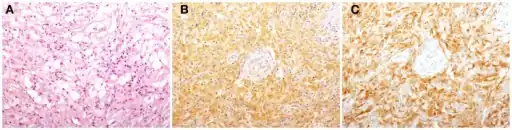

Histologically, ECD differs from Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in a number of ways. Unlike LCH, ECD does not stain positive for S-100 proteins or Group 1 CD1a glycoproteins, and electron microscopy of cell cytoplasm does not disclose Birbeck granules.[6] Tissue samples show xanthomatous or xanthogranulomatous infiltration by lipid-laden or foamy histiocytes, and are usually surrounded by fibrosis. Bone biopsy is said to offer the greatest likelihood of reaching a diagnosis. In some, there is histiocyte proliferation, and on staining, the section is CD68+ and CD1a-.

Treatment

Current treatment options for this condition include:

- Surgical debulking

- High-dose corticosteroid therapy

- Ciclosporin

- Interferon-α[9]

- Chemotherapy

- Vemurafenib. It would appear that approximately half these patients harbor point mutations of the BRAF gene at codon 600 substituting the amino acid glutamine for valine. Vemurafenib, an oral FDA approved targeted agent to the BRAF protein for melanoma, shows dramatic activity in patients Erdheim–Chester disease whose tumor contains the same mutation.[11] In 2017 the US FDA approved vemurafenib for this indication.[12]

- Radiation therapy

All current treatments have had varying degrees of success.

The vinca alkaloids and anthracyclines have been used most commonly in ECD treatment.[13]

Prognosis

Erdheim–Chester disease is associated with high mortality rates.[10][14] In 2005, the survival rate was below 50% at three years from diagnosis.[15] More recent reports of patients treated with Interferon therapy describe an overall 5-year survival of 68%.[16] Long-term survival is currently even more promising, although this impression is not reflected in the recent literature.[17]

Epidemiology

Approximately 500 cases have been reported in the literature to date.[18] ECD affects predominantly adults, with a mean age of 53 years.[6]

History

The first case of ECD was reported by the American pathologist William Chester in 1930, during his visit to the Austrian pathologist Jakob Erdheim in Vienna.[19]

Society and culture

Support groups

The Erdheim–Chester Disease Global Alliance Archived 2021-06-09 at the Wayback Machine is a support and advocacy group with the goal of raising awareness of and promoting research into ECD.[20][21] ECD families and patients are also supported by the Histiocytosis Association, Inc.[21][22]

Media

In the TV show House, season 2 episode 17, "All In", the final diagnosis of a 6-year-old boy who presents with bloody diarrhea and ataxia is Erdheim–Chester disease.

References

- ↑ "Erdheim-Chester Disease Declared a Histiocytic Neoplasm" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ↑ "Erdheim–Chester disease at the United States National Library of Medicine". Archived from the original on 2004-11-19. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ↑ "Erdheim-Chester Disease - Histiocytosis Association". www.histio.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ Lutz, S; Schmalzing, M; Vogel-Claussen, J; Adam, P; May, A (2011). "Rezidivierender Perikarderguss als Erstmanifestation eines Morbus Erdheim-Chester" [Recurrent pericardial effusion as first manifestation of Erdheim-Chester disease]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (in Deutsch). 136 (39): 1952–6. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1286368. PMID 21935854.

- ↑ Haroche, Julien; Amoura, Zahir; Touraine, Philippe; Seilhean, Danielle; Graef, Claire; Birmelé, Béatrice; Wechsler, Bertrand; Cluzel, Philippe; et al. (2007). "Bilateral Adrenal Infiltration in Erdheim-Chester Disease. Report of Seven Cases and Literature Review". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 92 (6): 2007–12. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2018. PMID 17405844.

- 1 2 3 Veyssier-Belot, Catherine; Cacoub, Patrice; Caparros-Lefebvre, Dominique; Wechsler, Janine; Brun, Bernard; Remy, Martine; Wallaert, Benoit; Petit, Henri; et al. (1996). "Erdheim-Chester Disease". Medicine. 75 (3): 157–69. doi:10.1097/00005792-199605000-00005. PMID 8965684. S2CID 32150913.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Erdheim Chester disease". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ Weidauer, Stefan; von Stuckrad-Barre, Sebastian; Dettmann, Edgar; Zanella, Friedhelm E.; Lanfermann, Heinrich (2003). "Cerebral Erdheim-Chester disease: Case report and review of the literature". Neuroradiology. 45 (4): 241–5. doi:10.1007/s00234-003-0950-z. PMID 12687308. S2CID 9513277.

- 1 2 "Erdheim Chester Disease". M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Archived from the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- 1 2 Egan, Aoife; Sorajja, Dan; Jaroszewski, Dawn; Mookadam, Farouk (2012). "Erdheim–Chester disease: The role of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in diagnosing and treating cardiac involvement". International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 3 (3): 107–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.12.001. PMC 3267285. PMID 22288060.

- ↑ Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile JF, Arnaud L, Maksud P, Charlotte F, Cluzel P, Drier A, Hervier B, Benameur N, Besnard S, Donadieu J, Amoura Z (Feb 2013). "Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation". Blood. 121 (9): 1495–500. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-07-446286. PMID 23258922.

- ↑ "FDA Approves First Treatment for Erdheim-Chester Disease. Nov 2017". Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- ↑ Gupta, Anu; Kelly, Benjamin; McGuigan, James E. (2002). "Erdheim-Chester Disease with Prominent Pericardial Involvement". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 324 (2): 96–100. doi:10.1097/00000441-200208000-00008. PMID 12186113. S2CID 24258121.

- ↑ Myra, C; Sloper, L; Tighe, PJ; McIntosh, RS; Stevens, SE; Gregson, RH; Sokal, M; Haynes, AP; Powell, RJ (2004). "Treatment of Erdheim-Chester disease with cladribine: A rational approach". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 88 (6): 844–7. doi:10.1136/bjo.2003.035584. PMC 1772168. PMID 15148234.

- ↑ Braiteh, F.; Boxrud, C; Esmaeli, B; Kurzrock, R (2005). "Successful treatment of Erdheim-Chester disease, a non-Langerhans-cell histiocytosis, with interferon-". Blood. 106 (9): 2992–4. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2238. PMID 16020507.

- ↑ Arnaud, L.; Hervier, B; et al. (2011). "CNS involvement and treatment with interferon are independent prognostic factors in Erdheim-Chester Disease; a multicenter survival analysis of 53 patients". Blood. 117 (10): 2778–2782. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-06-294108. PMID 21239701.

- ↑ Diamond, E; Dagna, L; et al. (2014). "Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical management of Erdheim-Chester disease". Blood. 124 (4): 483–492. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-561381. PMC 4110656. PMID 24850756.

- ↑ Haroche J1 Arnaud L, Cohen-Aubart F, Hervier B, Charlotte F, Emile JF, Amoura Z (2014). "Erdheim-Chester disease". Curr Rheumatol Rep. 16 (4): 412. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0412-0. PMID 24532298.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chester, William (1930). "Über Lipoidgranulomatose". Virchows Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medizin. 279 (2): 561–602. doi:10.1007/BF01942684. S2CID 27359311.

- ↑ "Erdheim–Chester Disease". ECD Global Alliance. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- 1 2 "Erdheim Chester disease - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "What Do I Do Now? - Erdheim-Chester Disease - Histiocytosis Association". www.histio.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

Further reading

- Aouba, Achille; Georgin-Lavialle, Sophie; Pagnoux, Christian; Silva, Nicolas Martin; Renand, Amédée; Galateau-Salle, Françoise; Le Toquin, Sophie; Bensadoun, Henri; et al. (2010). "Rationale and efficacy of interleukin-1 targeting in Erdheim–Chester disease". Blood. 116 (20): 4070–6. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279240. PMID 20724540.

- Arnaud, Laurent; Malek, Zoulikha; Archambaud, Frédérique; Kas, Aurélie; Toledano, Dan; Drier, Aurélie; Zeitoun, Delphine; Cluzel, Philippe; et al. (2009). "18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scanning is more useful in followup than in the initial assessment of patients with Erdheim-Chester disease". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 60 (10): 3128–38. doi:10.1002/art.24848. PMID 19790052.

- Arnaud, Laurent; Pierre, Isabelle; Beigelman-Aubry, Catherine; Capron, Frédérique; Brun, Anne-Laure; Rigolet, Aude; Girerd, Xavier; Weber, Nina; et al. (2010). "Pulmonary involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease: A single-center study of thirty-four patients and a review of the literature". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 62 (11): 3504–12. doi:10.1002/art.27672. PMID 20662053.

- Boissel, Nicolas; Wechsler, Bertrand; Leblond, Véronique (2001). "Treatment of Refractory Erdheim–Chester Disease with Double Autologous Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation". Annals of Internal Medicine. 135 (9): 844–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00027. PMID 11694122. Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- Braiteh, Fadi; Boxrud, Cynthia; Esmaeli, Bita; Kurzrock, Razelle (2005). "Successful treatment of Erdheim-Chester disease, a non–Langerhans-cell histiocytosis, with interferon-α". Blood. 106 (9): 2992–4. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2238. PMID 16020507.

- Brun, Anne-Laure; Touitou-Gottenberg, Diane; Haroche, Julien; Toledano, Dan; Cluzel, Philippe; Beigelman-Aubry, Catherine; Piette, Jean-Charles; Amoura, Zahir; Grenier, Philippe A. (2010). "Erdheim-Chester disease: CT findings of thoracic involvement". European Radiology. 20 (11): 2579–87. doi:10.1007/s00330-010-1830-7. PMID 20563815. S2CID 5775587.

- De Abreu, Marcelo Rodrigues; Castro, Miguel Oliveira; Chung, Christine; Trudell, Debra; Biswal, Sandip; Wesselly, Michelle; Resnick, Donald (2009). "Erdheim–Chester disease: Case report with unique postmortem magnetic resonance imaging, high-resolution radiography, and pathologic correlation". Clinical Imaging. 33 (2): 150–3. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.09.009. PMID 19237062.

- Drier, A.; Haroche, J.; Savatovsky, J.; Godeneche, G.; Dormont, D.; Chiras, J.; Amoura, Z.; Bonneville, F. (2010). "Cerebral, Facial, and Orbital Involvement in Erdheim-Chester Disease: CT and MR Imaging Findings". Radiology. 255 (2): 586–94. doi:10.1148/radiol.10090320. PMID 20413768.

- Haroche, J; Amoura, Z; Dion, E; Wechsler, B; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N; Cacoub, P; Isnard, R; Généreau, T; et al. (2004). "Cardiovascular involvement, an overlooked feature of Erdheim-Chester disease: Report of 6 new cases and a literature review". Medicine. 83 (6): 371–92. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000145368.17934.91. PMID 15525849. S2CID 1426013.

- Haroche, J.; Cluzel, P.; Toledano, D.; Montalescot, G.; Touitou, D.; Grenier, P. A.; Piette, J.-C.; Amoura, Z. (2009). "Cardiac Involvement in Erdheim-Chester Disease: Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomographic Scan Imaging in a Monocentric Series of 37 Patients". Circulation. 119 (25): e597–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825075. PMID 19564564.

- Haroche, Julien; Amoura, Zahir; Trad, Salim G.; Wechsler, Bertrand; Cluzel, Philippe; Grenier, Philippe A.; Piette, Jean-Charles (2006). "Variability in the efficacy of interferon-α in Erdheim-Chester disease by patient and site of involvement: Results in eight patients". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 54 (10): 3330–6. doi:10.1002/art.22165. PMID 17009306.

- Haroche, Julien; Amoura, Zahir; Charlotte, Frédéric; Salvatierra, Juan; Wechsler, Bertrand; Graux, Carlos; Brousse, Nicole; Piette, Jean-Charles (2008). "Imatinib mesylate for platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta–positive Erdheim-Chester histiocytosis". Blood. 111 (11): 5413–5. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-148304. PMID 18502845.

- Janku, F.; Amin, H. M.; Yang, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; Trent, J. C.; Kurzrock, R. (2010). "Response of Histiocytoses to Imatinib Mesylate: Fire to Ashes". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 28 (31): e633–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9073. PMID 20733125.

- Lachenal, Florence; Cotton, François; Desmurs-Clavel, Hélène; Haroche, Julien; Taillia, Hervé; Magy, Nadine; Hamidou, Mohamed; Salvatierra, Juan; et al. (2006). "Neurological manifestations and neuroradiological presentation of Erdheim-Chester disease: Report of 6 cases and systematic review of the literature". Journal of Neurology. 253 (10): 1267–77. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0160-9. PMID 17063320. S2CID 27976718.

- Mossetti, G; Rendina, D; Numis, FG; Somma, P; Postiglione, L; Nunziata, V (2003). "Biochemical markers of bone turnover, serum levels of interleukin-6/interleukin-6 soluble receptor and bisphosphonate treatment in Erdheim-Chester disease". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 21 (2): 232–6. PMID 12747282.

- Perlat, Antoinette; Decaux, Olivier; Sébillot, Martine; Grosbois, Bernard; Desfourneaux, Véronique; Meadeb, Jean (2009). "Erdheim-Chester disease with predominant mesenteric localization: Lack of efficacy of interferon alpha". Joint Bone Spine. 76 (3): 315–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.09.013. PMID 19119043.

External links

| Classification |

|---|