High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

| High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia |

| |

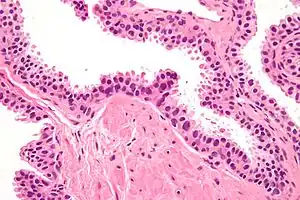

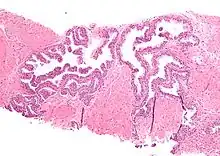

| Micrograph showing high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Urology |

High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) is an abnormality of prostatic glands and believed to precede the development of prostate adenocarcinoma (the most common form of prostate cancer).[1][2]

It may be referred to simply as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). It is considered to be a pre-malignancy, or carcinoma in situ, of the prostatic glands.

Signs and symptoms

HGPIN in isolation is asymptomatic. It is typically discovered in prostate biopsies taken to rule-out prostate cancer and very frequently seen in prostates removed for prostate cancer.

Relation to prostate cancer

There are several reasons why PIN is the most likely prostate cancer precursor.[3] PIN is more common in men with prostate cancer. High grade PIN can be found in 85 to 100% of radical prostatectomy specimens,[4] nearby or even in connection with prostate cancer. It tends to occur in the peripheral zone of the prostate. With age, it becomes increasingly multifocal, like prostate cancer. Molecular analysis has shown that high grade PIN and prostate cancer share many genetic abnormalities.[5]

The risk for men with high grade PIN of being diagnosed with prostate cancer after repeat biopsy has decreased since the introduction of biopsies at more than six locations (traditional sextant biopsies).[3]

Histology

HGPIN typically has one of four different histologic patterns:[2]

- tufted,

- micropapillary,

- cribriform and,

- flat.

Its cytologic features are that of prostatic adenocarcinoma:

- presence of nucleoli,

- increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and,

- increased nuclear size.

Microscopically, PIN is a collection of irregular, atypical epithelial cells. The architecture of the glands and ducts remains normal. The epithelial cells proliferate and crowding results in a pseudo-multilayer appearance. They remain fully contained within a prostate acinus (the berry-shaped termination of a gland, where the secretion is produced) or duct. The latter can be demonstrated with special staining techniques (immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins) to identify the basal cells forming the supporting layer of the acinus. In prostate cancer, the abnormal cells spread beyond the boundaries of the acinus and form clusters without basal cells. In HGPIN, the basal cell layer is disrupted but present. PIN is primarily found in the peripheral zone of the prostate (75-80%), rarely in the transition zone (10-15%) and very rarely in the central zone (5%), a distribution that parallels the zonal distribution for prostate carcinoma.[6]

Because it is thought to be a premalignant state, PIN is often considered the prostate equivalent of what is called carcinoma in situ (localized cancer) in other organs. However, PIN differs from carcinoma in situ in that it may remain unchanged or even spontaneously regress.

Several architectural variants of PIN have been described, and many cases have multiple patterns. The main ones are tufting, micropapillary, cribriform, and flat. Although these different appearances may cause confusion with other conditions, they have not been found to be of clinical importance. Rarer types are signet-ring-cell, small-cell-neuroendocrine, mucinous, foamy, inverted, and with squamous differentiation.[3]

Diagnosis

HGPIN is diagnosed from tissue by a pathologist, which may come from:

- a needle biopsy taken via the rectum and,

- surgical removal of prostate tissue:

- transurethral resection of the prostate - removal of extra prostate tissue to improve urination (a treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia),

- radical prostatectomy - complete removal of prostate and seminal vesicles (a treatment for prostate cancer).

Blood tests for prostate specific antigen (PSA), digital rectal examination, ultrasound scanning of the prostate via the rectum, fine needle aspiration or medical imaging studies (such as magnetic resonance imaging) are not useful for diagnosing HGPIN.

Treatment

HGPIN in isolation does not require treatment. In prostate biopsies it is not predictive of prostate cancer in one year if the prostate was well-sampled, i.e. if there were 8 or more cores.[7]

The exact timing of repeat biopsies remains an area of controversy, as the time required for, and probability of HGPIN transformations to prostate cancer are not well understood.

Prognosis

On a subsequent biopsy, given a history of a HGPIN diagnosis, the chance of finding prostatic adenocarcinoma is approximately 30%.[8]

History

PIN was historically subdivided into different stages, based on the level of cell atypia. PIN was formerly classified as PIN 1, 2 or 3, in order of increasing cell irregularities. Nowadays, PIN 1 is referred to as low grade PIN, and PIN 2 and PIN 3 are grouped together as high grade PIN.[9] Only high grade PIN has been shown to be a risk factor for prostate cancer. Because low grade PIN has no significance and does not require repeat biopsies or treatment, it is not mentioned in pathology reports. As such, PIN has become synonymous with high grade PIN.

See also

References

- ↑ Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L, Scarpelli M (June 2007). "Mechanisms of disease: high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and other proposed preneoplastic lesions in the prostate". Nat Clin Pract Urol. 4 (6): 321–32. doi:10.1038/ncpuro0815. PMID 17551536.

- 1 2 Bostwick DG, Qian J (March 2004). "High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia". Mod. Pathol. 17 (3): 360–79. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800053. PMID 14739906.

- 1 2 3 Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L, Scarpelli M (June 2007). "Mechanisms of disease: high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and other proposed preneoplastic lesions in the prostate". Nat Clin Pract Urol. 4 (6): 321–32. doi:10.1038/ncpuro0815. PMID 17551536.

- ↑ Godoy G, Taneja SS (2008). "Contemporary clinical management of isolated high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia". Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 11 (1): 20–31. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4501014. PMID 17909565.

- ↑ Hughes C, Murphy A, Martin C, Sheils O, O'Leary J (July 2005). "Molecular pathology of prostate cancer". J. Clin. Pathol. 58 (7): 673–84. doi:10.1136/jcp.2002.003954. PMC 1770715. PMID 15976331.

- ↑ Ayala, AG; Ro, JY (August 2007). "Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: recent advances". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 131 (8): 1257–66. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2007)131[1257:PINRA]2.0.CO;2. PMID 17683188.

- ↑ Herawi, M.; Kahane, H.; Cavallo, C.; Epstein, JI. (Jan 2006). "Risk of prostate cancer on first re-biopsy within 1 year following a diagnosis of high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is related to the number of cores sampled". J Urol. 175 (1): 121–4. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00064-9. PMID 16406886.

- ↑ Leite KR, Camara-Lopes LH, Cury J, Dall'oglio MF, Sañudo A, Srougi M (June 2008). "Prostate cancer detection at rebiopsy after an initial benign diagnosis: results using sextant extended prostate biopsy". Clinics. 63 (3): 339–42. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322008000300009. PMC 2664245. PMID 18568243.

- ↑ Montironi R, Mazzucchelli R, Algaba F, Lopez-Beltran A (September 2000). "Morphological identification of the patterns of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and their importance". J. Clin. Pathol. 53 (9): 655–65. doi:10.1136/jcp.53.9.655. PMC 1731241. PMID 11041054.