Choriocarcinoma

| Choriocarcinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

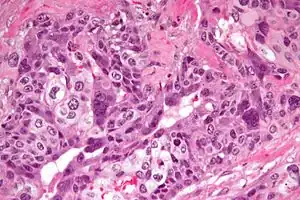

| Micrograph of choriocarcinoma showing both of the components necessary for the diagnosis - cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts. The syncytiotrophoblasts are multinucleated and have a dark staining cytoplasm. The cytotrophoblasts are mononuclear and have a pale staining cytoplasm. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Choriocarcinoma is a malignant, trophoblastic[1] cancer, usually of the placenta. It is characterized by early hematogenous spread to the lungs. It belongs to the malignant end of the spectrum in gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). It is also classified as a germ cell tumor and may arise in the testis or ovary.

Signs and symptoms

- increased quantitative chorionic gonadotropin (the "pregnancy hormone") levels

- vaginal bleeding

- shortness of breath

- hemoptysis (coughing up blood)

- chest pain

- chest X-ray shows multiple infiltrates of various shapes in both lungs

- presents in males as a testicular cancer, sometimes with skin hyperpigmentation (from excess chorionic gonadotropin cross reacting with the alpha MSH receptor), gynecomastia, and weight loss (from excess chorionic gonadotropin cross reacting with the LH, FSH, and TSH receptor) in males

- can present with decreased thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) due to hyperthyroidism.

Cause

Choriocarcinoma of the placenta during pregnancy is preceded by:

- hydatidiform mole (50% of cases)

- spontaneous abortion (20% of cases)

- ectopic pregnancy (2% of cases)

- normal term pregnancy (20–30% of cases)

- hyperemesis gravidarum

Rarely, choriocarcinoma occurs in primary locations other than the placenta; very rarely, it occurs in testicles. Although trophoblastic components are common components of mixed germ cell tumors, pure choriocarcinoma of the adult testis is rare. Pure choriocarcinoma of the testis represents the most aggressive pathologic variant of germ cell tumors in adults, characteristically with early hematogenous and lymphatic metastatic spread. Because of early spread and inherent resistance to anticancer drugs, patients have poor prognosis. Elements of choriocarcinoma in a mixed testicular tumor have no prognostic importance.[2][3]

Choriocarcinomas can also occur in the ovaries[4][5] and other organs.[6]

Pathology

Characteristic feature is the identification of intimately related syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts without formation of definite placental type villi. Since choriocarcinomas include syncytiotrophoblasts (beta-HCG producing cells), they cause elevated blood levels of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin.

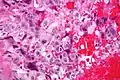

Syncytiotrophoblasts are large multi-nucleated cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. They often surround the cytotrophoblasts, reminiscent of their normal anatomical relationship in chorionic villi. Cytotrophoblasts are polyhedral, mononuclear cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and a clear or pale cytoplasm. Extensive hemorrhage is a common finding.

High mag.

High mag. Very high mag.

Very high mag.

Treatment

Since gestational choriocarcinoma (which arises from a hydatidiform mole) contains paternal DNA (and thus paternal antigens), it is exquisitely sensitive to chemotherapy. The cure rates, even for metastatic gestational choriocarcinoma, more than 90% when using chemotherapy for invasive mole and choriocarcinoma.[7]

As of 2019, treatment with either single-agent methotrexate or actinomycin-D is recommended for low-risk disease, while intense combination regimens including EMACO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide and vincristine (Oncovin) are recommended for intermediate or high-risk disease.[8][9][10]

Hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) can also be offered[11] to patients > 40 years of age or those for whom sterilisation is not an obstacle. It may be required for those with severe infection and uncontrolled bleeding.

Choriocarcinoma arising in the testicle is rare, malignant and highly resistant to chemotherapy. The same is true of choriocarcinoma arising in the ovary. Testicular choriocarcinoma has the worst prognosis of all germ-cell cancers.[12]

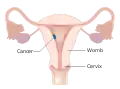

Stage I choriocarcinoma

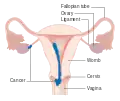

Stage I choriocarcinoma Stage 2 choriocarcinoma

Stage 2 choriocarcinoma Stage 3 choriocarcinoma

Stage 3 choriocarcinoma Stage 4 choriocarcinoma

Stage 4 choriocarcinoma

References

- ↑ "choriocarcinoma" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Rosenberg S, DePinho RA, Weinberg RE, DeVita VT, Lawrence TS (2008). DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7207-5. OCLC 192027662.

- ↑ Kufe D (2000). Benedict RC, Holland JF (eds.). Cancer medicine (5th ed.). Hamilton, Ont: B.C. Decker. ISBN 1-55009-113-1. OCLC 156944448.

- ↑ Gerson RF, Lee EY, Gorman E (November 2007). "Primary extrauterine ovarian choriocarcinoma mistaken for ectopic pregnancy: sonographic imaging findings". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 189 (5): W280–W283. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.0814. PMID 17954626.

- ↑ Ozdemir I, Demirci F, Yucel O, Demirci E, Alper M (May 2004). "Pure ovarian choriocarcinoma: a difficult diagnosis of an unusual tumor presenting with acute abdomen in a 13-year-old girl". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 83 (5): 504–505. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00092a.x. PMID 15059168. S2CID 20068680.

- ↑ Snoj Z, Kocijancic I, Skof E (March 2017). "Primary pulmonary choriocarcinoma". Radiology and Oncology. 51 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1515/raon-2016-0038. PMC 5330166. PMID 28265226.

- ↑ Biscaro A, Braga A, Berkowitz RS (January 2015). "Diagnosis, classification and treatment of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 37 (1): 42–51. doi:10.1590/SO100-720320140005198. PMID 25607129.

- ↑ Braga A, Mora P, de Melo AC, Nogueira-Rodrigues A, Amim-Junior J, Rezende-Filho J, Seckl MJ (February 2019). "Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia worldwide". World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 10 (2): 28–37. doi:10.5306/wjco.v10.i2.28. PMC 6390119. PMID 30815369.

- ↑ Rustin GJ, Newlands ES, Begent RH, Dent J, Bagshawe KD (July 1989). "Weekly alternating etoposide, methotrexate, and actinomycin/vincristine and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy for the treatment of CNS metastases of choriocarcinoma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 7 (7): 900–903. doi:10.1200/JCO.1989.7.7.900. PMID 2472471.

- ↑ Katzung BG (2006). "Cancer Chemotherapy". Basic and clinical pharmacology (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 0-07-145153-6. OCLC 157011367.

- ↑ Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC (October 2006). "Role of surgery in the management of high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 51 (10): 773–776. PMID 17086805.

- ↑ Verville KM (2009). Testicular Cancer. Infobase Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 9781604131666.