Human anus

| Anus | |

|---|---|

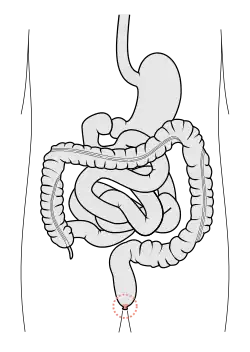

Scheme of digestive tract, with anus marked. | |

The anus of a female with a prominent perineal raphe (left) and a male with anal pubic hair (right). | |

| Identifiers | |

| TA98 | A05.7.05.013 |

| TA2 | 3022 |

| FMA | 15711 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

In humans, the anus (from Latin anus meaning "ring", "circle")[1][2] is the external opening of the rectum, located inside the intergluteal cleft and separated from the genitals by the perineum. Two sphincters control the exit of feces from the body during an act of defecation, which is the primary function of the anus. These are the internal anal sphincter and the external anal sphincter, which are circular muscles that normally maintain constriction of the orifice and which relaxes as required by normal physiological functioning. The inner sphincter is involuntary and the outer is voluntary. It is located behind the perineum which is located behind the vagina or scrotum.

In part owing to its exposure to feces, a number of medical conditions may affect the anus such as hemorrhoids.[3] The anus is the site of potential infections and other conditions, including cancer (see Anal cancer).[4]

With anal sex, the anus can play a role in sexuality. Attitudes toward anal sex vary, and it is illegal in some countries.[5] The anus is often considered a taboo part of the body,[5] and is known by many usually vulgar slang terms. Some sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS and anal warts can be spread via anal sex.

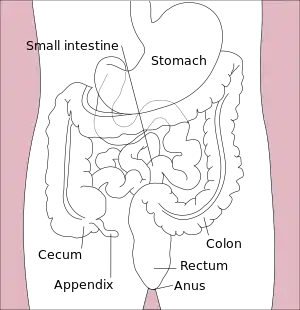

Structure

The anus is the final part of the gastrointestinal tract, and directly continues from the rectum. The anus passes through the pelvic floor. The anus is surrounded by muscles. The top and bottom of the anus are surrounded by the internal and external anal sphincters, two muscular rings which control defecation.[6]: 397 The anus is surrounded in its length by folds called anal valves, which converge at a line known as the pectinate line. This represents the point of transition between the hindgut and the ectoderm in the embryo. Below this point, the mucosa of the internal anus becomes skin.[6] : 397 The pectinate line is also the division between the internal and external anus.

The anus receives blood from the inferior rectal artery and innervation from the inferior rectal nerves, which branch from the pudendal nerve.[7]

Microanatomy

The pseudostratified columnar epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract transitions to stratified squamous epithelium at the pectinate line. The stratified squamous epithelium gradually accumulates sebaceous and apocrine glands.[8] : 285

Development

During puberty, as testosterone triggers androgenic hair growth on the body, pubic hair begins to appear around the anus. Although initially sparse, it fills out by the end of puberty, if not earlier. In some genetic populations, androgenic hair is less common.

Function

Defecation

Intra-rectal pressure builds as the rectum fills with feces, pushing the feces against the walls of the anal canal. Contractions of abdominal and pelvic floor muscles can create intra-abdominal pressure which further increases intra-rectal pressure. The internal anal sphincter (an involuntary muscle) responds to the pressure by relaxing, thus allowing the feces to enter the canal. The rectum shortens as feces are pushed into the anal canal and peristaltic waves push the feces out of the rectum. Relaxation of the internal and external anal sphincters allows the feces to exit from the anus, finally, as the levator ani muscles pull the anus up over the exiting feces.

Clinical significance

Anal fissures, which are tears in the external lining of the lining (mucosa) of the anus. These are exquisitely painful, with pain occurring after a motion is passed; other symptoms may include minor bleeding, discharge, or itch.[9] Generally, fissures are due to injury to the mucosa, or because of a poor local blood supply that prevents proper healing, with spasm of the external anal sphincter contributing.[9] The external anal sphincter can be relaxed by the application of glyceryl trinitrate creams, and constipation is managed with laxatives and improving hydration.[9] Some fissures may require botulinum toxin injection; worst cases may require surgical intervention such as "lateral internal anal sphincterotomy or advancement anoplasty".[9]

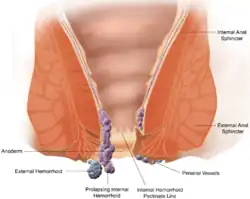

Hemorrhoids, which are visible blood vessels from the internal or external venous plexuses of the anus. Haemorrhoids may cause bleeding after passing a motion; may be painful; may cause an itch; may prolapse out of the anus.[9] Haemorrhoids are often associated with straining due to constipation, and pregnancy.[9] Usually, haemorrhoids are managed with medications to make motions more soft and prevent straining during constipation. Some haemorrhoids require surgery to manage, which may involve placing a band around the haemorrhoid, in order for it to lose blood supply; or surgical excision.[9]

Other

- Fistula

- Birth defects, including imperforation, stenosis, Tailgut cyst

Infections

Anal abscesses usually result from infection of the normal glands of the anus, or sometimes because of Crohn's disease.[9] They usually occur to the sides of the sphincters, and between the internal and external sphincters, either on the surface, or deeper. They may get bigger, enlarging in the direction of the rectum, and resulting in an abnormal connection called an anorectal fistula. They are usually managed with surgical drainage[9] and antibiotics.[10][11]

Additional

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Anal warts, also called "anal condyloma"

Cancer

Anal cancer, also called "anal carcinoma", and Anal intraepithelial neoplasia[12]

Itching, incontinence and constipation

Itchiness called Pruritus ani, can affect the anus area. It is most often due to long-term exposure of the anus to faeces, with reasons including diseases of the anus such as haemorrhoids, fistulas and fissures; poor hygiene or chronic diarrhoea; local infections such as tapeworm and thrush, skin conditions such as psoriasis and contact dermatitis. If there is a specific cause identified, the cause may be treated to relieve the itch. Otherwise, treatment includes keeping the area clean and dry, ceasing topical creams and ointments, and potentially bulk-forming laxatives to reduce the chance of faecal contamination.[9]

Damage or injury to the anal sphincter (patulous anus in more severe cases) as a result of damage during surgery, such as to the perineal region, or resulting from anal sex; can lead to flatus and/or fecal incontinence, chronic constipation and megacolon.[13]

A Grade IV hemorrhoid protrudes out of the anus.

A Grade IV hemorrhoid protrudes out of the anus.

Society and culture

Sexuality

The anus has a relatively high concentration of nerve endings and can be an erogenous zone, which can make anal intercourse pleasurable if performed properly. The pudendal nerve that branches to supply the external anal sphincter also branches to the dorsal nerve of the clitoris and the dorsal nerve of the penis.[14]

In addition to nerve endings, pleasure from anal intercourse may be aided by the close proximity between the anus and the prostate for males, and vagina, clitoral legs and anal area for females. This is because of indirect stimulation of the prostate and vagina or clitoral legs.[14][15][16] For a male insertive partner, the tightness of the anus can be a source of pleasure via the tactile pressure on the penis.[17][18] Pleasure from the anus can also be achieved through anal masturbation, fingering,[5] facesitting, anilingus, and other penetrative and non-penetrative acts. Anal stretching or fisting is pleasurable for some, but it poses a more serious threat of damage due to the deliberate stretching of the anal and rectal tissues; its injuries include anal sphincter lacerations and rectal and sigmoid colon (rectosigmoid) perforation, which might result in death.[19] Lubricant and condoms are widely regarded as a necessity while performing anal sex as well as a slow and cautious penetration.[20]

Anal intercourse is sometimes referred to as sodomy or buggery, and is considered taboo in a number of legal systems. It has been, and in some jurisdictions continues to be, a crime carrying severe punishment.[5]

Hygiene

To prevent diseases of the anus and to promote general hygiene, humans often clean the exterior of the anus after emptying the bowels. A rinse with water from a bidet or a wipe with toilet paper is often used for this purpose, though anal cleansing practices vary greatly between cultures.

Cosmetics

Shaving, trimming, depilatory (hair removal), or Brazilian waxing can clear the perineum of hair.

Anal bleaching is a process in which the anus and perineum, which may darken after puberty depending on individual genetics, is lightened for a more youthful appearance.

True anal piercing is rare because it may interfere with the function of the anus. Surface piercings of the perineum are easier to care for and much more common.

Additional images

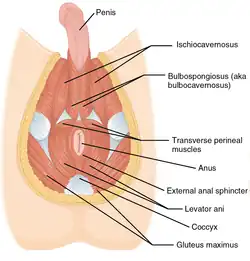

Muscles of the male perineum

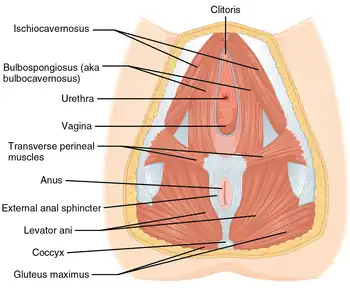

Muscles of the male perineum Muscles of the female perineum

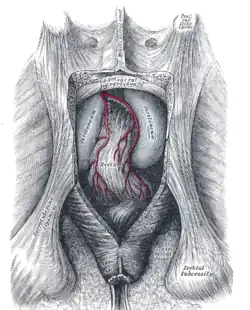

Muscles of the female perineum The posterior aspect of the rectum and anus exposed by removing the lower part of the sacrum and the coccyx

The posterior aspect of the rectum and anus exposed by removing the lower part of the sacrum and the coccyx

See also

| Look up anus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human anus. |

- Anal bleaching

- Anal stage (Freudian psychosexual stage)

- Anococcygeal nerve

- Buttocks

- Cloaca

- Coccydynia

- Coccyx

- Digestive system

- Flatulence

References

- ↑ Martim de Albuquerque (1873). Notes and Queries. Original from the University of Michigan: Oxford University Press. p. 119.

- ↑ Edward O'Reilly; John O'Donovan (1864). An Irish-English Dictionary. Original from Oxford University: J. Duffy. p. 7.

- ↑ Schubert, MC; Sridhar, S; Schade, RR; Wexner, SD (July 2009). "What every gastroenterologist needs to know about common anorectal disorders". World J Gastroenterol. 15 (26): 3201–09. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3201. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 2710774. PMID 19598294.

- ↑ "Anal Cancer". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Anal Sex, defined". Discovery.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, A. M. R. (2013-02-13). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451119459.

- ↑ Deakin, Barbara Young; et al. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas. drawings by Philip J. (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P. (eds.) (2018). "Anorectal disorders". Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 835–6. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

{{cite book}}:|first4=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Anorectal Abscess". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ Ansorge, R; Robinson, J (15 September 2019). "Anal Abscess". WebMD. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ "Anal Cancer". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ "Megacolon". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- 1 2 Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara; Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ↑ Natasha Janina, Valdez (2011). Vitamin O: Why Orgasms Are Vital to a Woman's Health and Happiness, and How to Have Them Every Time!. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-61608-311-3. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Anal Sex Safety and Health Concerns". WebMD. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ↑ Joann S. DeLora; Carol A. B. Warren; Carol Rinkleib Ellison (2008) [1981]. Understanding Sexual Interaction. Houghton Mifflin (Original from the University of Virginia). p. 123. ISBN 978-0-395-29724-7. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

Many men find anal intercourse more exciting than penile-vaginal intercourse because the anal opening is usually smaller and tighter than the vagina. Probably the forbidden aspect of anal intercourse also makes it more exciting for some people.

- ↑ John J. Miletich; Tia Laura Lindstrom (2010). An Introduction to the Work of a Medical Examiner: From Death Scene to Autopsy Suite. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 978-0275995089. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ↑ Carroll, Janell L. (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Retrieved 2010-12-19.