Intestinal atresia

| Intestinal atresia | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Bowel atresia | |

| |

| Radiograph with double bubble sign indicating duodenal atresia | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Vomiting bile, abdominal bloating, failure to pass meconium[1] |

| Complications | JIA: Short gut syndrome[1] DA: Hirschsprung disease[1] |

| Usual onset | Present at birth[1] |

| Types | Duodenal, jejunoileal, colonic[1] |

| Risk factors | JIA: Gastroschisis, cystic fibrosis[1] DA: Down syndrome[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Before birth: Ultrasound[1] After birth: X-ray[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Intestinal malrotation, volvulus, Hirschsprung disease[1] |

| Treatment | Nasogastric tube, intravenous fluids, surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | 90% survival[2] |

| Frequency | 1 in 3,000 newborns[1][3] |

Intestinal atresia is a birth defect of the intestines that causes bowel obstruction in the newborn.[1] There are three types duodenal (DA), jejunoileal (JIA), and colonic (CA).[1] Symptoms may include vomiting bile, abdominal bloating, and failure to pass meconium.[1] Complications of JIA may include short gut syndrome while complications of DA may include Hirschsprung disease.[1]

Risk factors for JIA include gastroschisis and cystic fibrosis while risk factors for DA include Down syndrome.[1] Diagnosis may occur by ultrasound before birth and X-ray after birth.[1] Other conditions that may present similarly include intestinal malrotation including volvulus, and Hirschsprung disease.[1]

Initial treatment involves nasogastric tube placement and intravenous fluids.[1] This is than followed by surgery and in JIA parenteral nutrition is often required until intestinal function has improved.[1] Procedurals to lengthen the intestines or small bowel transplant may occasionally be required.[1] The risk of death in DA is about 5% while that in CA is about 25%.[1]

Jejunoileal atresia affects between 1 to 3 in 10,000, while duodenal atresia affects about 1 in 10,000, and colonic atresia affects about 1 in 35,000 newborns.[1][3] The condition is the cause of about a third of cases of bowel obstruction in newborns.[2] It was first described in 1684 by Goeller.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The most prominent symptom of intestinal atresia is bilious vomiting soon after birth.[4] This is most common in jejunal atresia.[2] Other features include abdominal distension and failure to pass meconium. The distension is more generalised the further down the bowel the atresia is located and is thus most prominent with ileal atresia.[4][2] Inability to pass stool is most common with duodenal or jejunal atresia;[2] if stool is passed, it may be small, mucus-like and grey.[4] Occasionally, there may be jaundice, which is most common in jejunal atresia.[2] Abdominal tenderness or an abdominal mass are not generally seen as symptoms of intestinal atresia. Rather, abdominal tenderness is a symptom of the late complication meconium peritonitis.[4]

Before birth, excess amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios) is a possible symptom. This is more common in duodenal and oesophageal atresia.[4]

Cause

The most common cause of non-duodenal intestinal atresia is a vascular accident in utero that leads to decreased intestinal perfusion and ischemia of the respective segment of bowel.[3] This leads to narrowing, or in the most severe cases, complete obliteration of the intestinal lumen.

In the case that the superior mesenteric artery, or another major intestinal artery, is occluded, large segments of bowel can be entirely underdeveloped (Type III). Classically, the affected area of bowel assumes a spiral configuration and is described to have an "apple peel" like appearance; this is accompanied by lack of a dorsal mesentery (Type IIIb).

An inherited form – familial multiple intestinal atresia – has also been described. This disorder was first reported in 1971.[5] It is due to a mutation in the gene TTC7A on short arm of chromosome 2 (2p16). It is inherited as an autosomal recessive gene and is usually fatal in infancy.

Ileal atresia can also result as a complication of meconium ileus.

A third of infants with intestinal atresia are born prematurely[4] or with low birth weight.[2]

Diagnosis

Intestinal atresias are often discovered before birth; either during a routine sonogram which shows a dilated intestinal segment due to the blockage, or by the development of polyhydramnios (the buildup of too much amniotic fluid in the uterus). These abnormalities are indications that the fetus may have a bowel obstruction which a more detailed ultrasound study can confirm.[6] Infants with stenosis instead of atresia are often not discovered until several days after birth.[4]

Some fetuses with bowel obstruction have abnormal chromosomes. An amniocentesis is recommended because it can determine not only the sex of the baby, but whether or not there is a problem with the chromosomes.

If not diagnosed in utero, infants with intestinal atresia are typically diagnosed at day 1 or day 2 after presenting with eating problems, vomiting, and/or failure to have a bowel movement.[3] Diagnosis can be confirmed with an X-ray, and typically followed with an upper gastrointestinal series, lower gastrointestinal series, and ultrasound.[6][3]

Classification

By location

Intestinal atresia may be classified by its location. Patients may have intestinal atresia in multiple locations.[7]

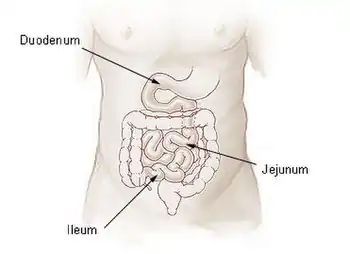

- Duodenal atresia – malformation of the duodenum, part of the intestine that empties from the stomach, and first section of the small intestine

- Jejunal atresia – malformation of the jejunum, the second part of the small intestine extending from the duodenum to the ileum, that causes the jejunum to block blood flow to the colon [8]

- Ileal atresia – malformation of the ileum, the lower part of the small intestine

- Colon atresia – malformation of the colon

Malformations may also occur along multiple portions of the intestinal tract; for instance a malformation that occurs along or spans the length of the jejunum and the ilieum is termed "jejunoileal atresia".[6][3]

By malformation

Intestinal atresia can also by classified by the type of malformation.[9] The classification system by Bland-Sutton and Louw and Barnard (1955)[10] initially divided them into three types.[9][6] This was later expanded to five by Zerella and Grosfeld et al.[2]

Type I

In type I, there is a wall (septum) or membrane at some point in the bowel, leading to dilation of the bowel on the nearer side and a collapse of the bowel on the latter side. Bowel length is not usually affected in this type.[4]

Type II

In type II, there is a gap in the bowel, and either end of the remaining intestine is closed off and connected to the other by a fibrous cord that runs along the edge of the mesentery. The mesentery remains intact.[4]

Type IIIa

Type IIIa is similar to type II, but the mesentery is defective (there is a V-shaped gap),[2] and the bowel length may be shortened.[4]

Type IIIb

In type IIIb, also known as the "apple peel" or "Christmas tree" deformity, the atresia affects the jejunum, and the intestine is often malrotated with most of the mesenteric arteries absent. The remaining ileum, which is of varying length, survives on a single mesenteric artery, which it is twisted around in a spiral form.[4] The term "apple-peel intestinal atresia" is generally reserved for when it affects the jejunum,[11][12] while "Christmas tree intestinal atresia" is used if it affects the duodenum. It may affect both, however.[7]

Type IV

Type IV involves a combination of all the other types and takes the appearance of a string of sausages. The length of the bowel is always shortened, but the last part of the ileum is usually not affected, as in type III.[4] This type usually affects the nearest end of the jejunum, but the far end of the ileum may instead be affected.[2]

Treatment

Fetal and neonatal intestinal atresia are treated using laparotomy after birth. If the area affected is small, the surgeon may be able to remove the damaged portion and join the intestine back together. In instances where the narrowing is longer, or the area is damaged and cannot be used for period of time, a temporary stoma may be placed.

The infant is usually given intravenous fluid hydration, and a nasogastric or orogastric tube may be used to aspirate the contents of the stomach. The nutritional administration is maintained after surgery until the bowel can resume normal function.[4]

Prognosis

Prognosis is usually good if treated with surgery in infancy. The main factor in mortality is the availability of care and appropriate parenteral nutrition after surgery until the bowel can resume normal function.[4]

The most common complication is pseudo-obstruction at the site of surgery due to pre-existing intestinal dysmotility. This can usually only be treated by non-surgical methods.[4]

If the atresia is not treated, the bowel may become perforated or ischemic. This can lead to abdominal tenderness and meconium peritonitis, which can be fatal.[4]

Epidemiology

Intestinal atresia occurs in around 1 in 3,000 births in the United States.[4] The most common form of intestinal atresia is duodenal atresia. It has a strong association with Down syndrome.[13] The second-most common type is ileal atresia. 95% of congenital jejunoileal obstructions are atresias; only 5% are stenoses.[2]

Prevalence of jejunoileal atresia is 1 to 3 in 10,000 live births. It is weakly associated with cystic fibrosis, intestinal malrotation, and gastroschisis.[3]

The frequencies of each type from Louw and Barnard's classification are as follows:[4][14][2]

- Type I: 19–23% of cases (mean: 20.6%)

- Type II:10–35% of cases (mean: 25.3%)

- Type IIIa: 15%–46% of cases (mean: 30%)

- Type IIIb ("apple-peel" type): 4–19% of cases (mean: 8.8%)

- Type IV: 6–32% of cases (mean: 15.9%). (Note: the mean percentages total higher than 100% due to rounding.)

History

Ileal atresia was first described in 1684 by Goeller. In 1812, Johann Friedrich Meckel reviewed the topic and speculated on an explanation. In 1889, English surgeon John Bland-Sutton proposed a classification system for intestinal atresia and suggested that it occurs at areas that are obliterated as part of normal development. In 1900, Austrian physician Julius Tandler first put forward the theory that it may be caused by lack of recanalisation during development.[2]

The vascular ischemic cause of non-duodenal atresia was confirmed by Louw and Barnard in 1955 and was repeated in later studies. It had first been proposed by N. I. Spriggs in 1912.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Adams, SD; Stanton, MP (December 2014). "Malrotation and intestinal atresias". Early human development. 90 (12): 921–5. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.09.017. PMID 25448782.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Prasad, T. R. Sai; Bajpai, M. (2000-09-01). "Intestinal atresia". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 67 (9): 671–678. doi:10.1007/BF02762182. ISSN 0973-7693. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 William J. Cochran, MD. "Jejunoileal Atresia - Pediatrics". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Alastair John Ward Millar, John R. Gosche, Kokila Lakhoo (2011). "Chapter 63 - Intestinal Atresia and Stenosis" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mishalany, Henry G.; Der Kaloustian, Vazken M. (July 1971). "Familial multiple-level intestinal atresias: Report of two siblings". The Journal of Pediatrics. 79 (1): 124–125. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80072-0. ISSN 0022-3476.

- 1 2 3 4 "Jejunoileal Atresia". Short Bowel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2019-02-04. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- 1 2 Federici, S.; Domenichelli, V.; Antonellini, C.; Dòmini, R. (August 2003). "Multiple intestinal atresia with apple peel syndrome: successful treatment by five end-to-end anastomoses, jejunostomy, and transanastomotic silicone stent". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 38 (8): 1250–1252. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(03)00281-1. ISSN 1531-5037. PMID 12891506.

- ↑ Jejunal Atresia. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6799/jejunal-atresia Archived 2018-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Shorter, Nicholas A.; Georges, Anthony; Perenyi, Agnes; Garrow, Eugene (Nov 2006). "A proposed classification system for familial intestinal atresia and its relevance to the understanding of the etiology of jejunoileal atresia". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 41 (11): 1822–1825. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.06.008. ISSN 0022-3468. PMID 17101351.

- ↑ Louw, J.H.; Barnard, C.N. (Nov 1955). "CONGENITAL INTESTINAL ATRESIA OBSERVATIONS ON ITS ORIGIN". The Lancet. 266 (6899): 1065–1067. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(55)92852-x. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Blyth, H; Dickson, J A (September 1969). "Apple peel syndrome (congenital intestinal atresia): a family study of seven index patients". Journal of Medical Genetics. 6 (3): 275–277. doi:10.1136/jmg.6.3.275. ISSN 0022-2593. PMC 1468754. PMID 5345098.

- ↑ Gaillard, Frank. "Apple-peel intestinal atresia". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- ↑ Le, Tao (2013). First Aid for the USMLE STEP. New York: Mc Graw Hill. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-07-180232-1.

- ↑ Federici, S.; Domenichelli, V.; Antonellini, C.; Dòmini, R. (2003-08-01). "Multiple intestinal atresia with apple peel syndrome: successful treatment by five end-to-end anastomoses, jejunostomy, and transanastomotic silicone stent". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 38 (8): 1250–1252. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(03)00281-1. ISSN 0022-3468. PMID 12891506. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

External links

| Classification |

|---|