Misconceptions about HIV/AIDS

The spread of HIV/AIDS has affected millions of people worldwide; AIDS is considered a pandemic.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2016 there were 36.7 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS, with 1.8 million new HIV infections per year and 1 million deaths due to AIDS.[2] Misconceptions about HIV and AIDS arise from several different sources, from simple ignorance and misunderstandings about scientific knowledge regarding HIV infections and the cause of AIDS to misinformation propagated by individuals and groups with ideological stances that deny a causative relationship between HIV infection and the development of AIDS. Below is a list and explanations of some common misconceptions and their rebuttals.

The relationship between HIV and AIDS

HIV is the same as AIDS

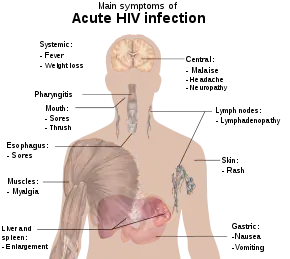

HIV is an acronym for human immunodeficiency virus, which is the virus that causes AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Contracting HIV can lead to the development of AIDS or stage 3 HIV, which causes serious damage to the immune system.[3] While this virus is the underlying cause of AIDS,[4] not all HIV-positive individuals have AIDS, as HIV can remain in a latent state for many years.[5] If undiagnosed or left untreated, HIV usually progresses to AIDS, defined as possessing a CD4+ lymphocyte count under 200 cells/μl or HIV infection plus co-infection with an AIDS-defining opportunistic infection. HIV cannot be cured, but it can be treated, and its transmission can be halted. Treating HIV can prevent new infections, which is the key to ultimately defeating AIDS.[6]

Treatment

Cure

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in many cases allows the stabilization of the patient's symptoms, partial recovery of CD4+ T-cell levels, and reduction in viremia (the level of virus in the blood) to low or near-undetectable levels. Disease-specific drugs can also alleviate symptoms of AIDS and even cure specific AIDS-defining conditions in some cases. Medical treatment can reduce HIV infection in many cases to a survivable chronic condition. However, these advances do not constitute a cure, since current treatment regimens cannot eradicate latent HIV from the body.

High levels of HIV-1 (often HAART-resistant) develop if treatment is stopped, if compliance with treatment is inconsistent, or if the virus spontaneously develops resistance to an individual's regimen.[7] Antiretroviral treatment known as post-exposure prophylaxis reduces the chance of acquiring an HIV infection when administered within 72 hours of exposure to HIV.[8] However, an overwhelming body of clinical evidence has demonstrated the U=U rule - if someone's viral load is undetectable (<200 viral copies per mL) they are untransmissible. Essentially this means if a person living with HIV is well controlled on medications with a viral load less than 200, they cannot transmit HIV to their partners via sexual contact. [9] The landmark study that first established this was the HPTN052 study, which looked at over 2000 couples over 10 years, where one partner was HIV positive, and the other partner was HIV negative. [10]

Sexual intercourse with a virgin will cure AIDS

The myth that sex with a virgin will cure AIDS is prevalent in South Africa.[11][12][13] Sex with an uninfected virgin does not cure an HIV-infected person, and such contact will expose the uninfected individual to HIV, potentially further spreading the disease. This myth has gained considerable notoriety as the perceived reason for certain sexual abuse and child molestation occurrences, including the rape of infants, in South Africa.[11][12]

Sexual intercourse with an animal will avoid or cure AIDS

In 2002, the National Council of Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (NSPCA) in Johannesburg, South Africa, recorded beliefs amongst youths that sex with animals is a means to avoid AIDS or cure it if infected.[14] As with "virgin cure" beliefs, there is no scientific evidence suggesting a sexual act can actually cure AIDS, and no plausible mechanism by which it could do so has ever been proposed. While the risk of contracting HIV via sex with animals is likely much lower than with humans due to HIV's inability to infect animals, the practice of bestiality still has the ability to infect humans with other fatal zoonotic diseases.

HIV antibody testing is unreliable

Diagnosis of infection using antibody testing is a well-established technique in medicine. HIV antibody tests exceed the performance of most other infectious disease tests in both sensitivity (the ability of the screening test to give a positive finding when the person tested truly has the disease) and specificity (the ability of the test to give a negative finding when the subjects tested are free of the disease under study). Many current HIV antibody tests have sensitivity and specificity in excess of 96% and are therefore extremely reliable.[15] While most patients with HIV show an antibody response after six weeks, window periods vary and may occasionally be as long as three months.[16]

Progress in testing methodology has enabled detection of viral genetic material, antigens, and the virus itself in bodily fluids and cells. While not widely used for routine testing due to high cost and requirements in laboratory equipment, these direct testing techniques have confirmed the validity of the antibody tests.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

Positive HIV antibody tests are usually followed up by retests and tests for antigens, viral genetic material and the virus itself, providing confirmation of actual infection.

HIV infection

HIV can be spread through casual contact with an HIV infected individual

One cannot become infected with HIV through normal contact in social settings, schools, or in the workplace. Other examples of casual contact in which HIV infection will not occur include shaking someone's hand, hugging or "dry" kissing someone, using the same toilet or drinking from the same glass as an HIV-infected person, and being exposed to coughing or sneezing by an infected person.[23][24] Saliva carries a negligible viral load, so even open-mouthed kissing is considered a low risk. However, if the infected partner or both of the performers have blood in their mouth due to cuts, open sores, or gum disease, the risk increases. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has only recorded one case of possible HIV transmission through kissing (involving an HIV-infected man with significant gum disease and a sexual partner also with significant gum disease),[25] and the Terence Higgins Trust says that this is essentially a no-risk situation.[26]

Other interactions that could theoretically result in person-to-person transmission include caring for nose bleeds and home health care procedures, yet there are very few recorded incidents of transmission occurring in these ways. A handful of cases of transmission via biting have occurred, though this is extremely rare.[27]

HIV-positive individuals can be detected by their appearance

Due to media images of the effects of AIDS, many people believe that individuals infected with HIV always appear a certain way, or at least appear different from an uninfected, healthy person. In fact, disease progression can occur over a long period of time before the onset of symptoms, and as such, HIV infections cannot be detected based on appearance.[28]

HIV cannot be transmitted through oral sex

Contracting HIV through oral sex is possible, but it is much less likely than from anal sex and penile–vaginal intercourse.[29] No cases of such a transmission were observed in a sample of 8965 people performing receptive oral sex.[30]

HIV is transmitted by mosquitoes

When mosquitoes bite a person, they do not inject the blood of a previous victim into the person they bite next. Mosquitoes do, however, inject their saliva into their victims, which may carry diseases such as dengue fever, malaria, yellow fever, or West Nile virus and can infect a bitten person with these diseases. HIV is not transmitted in this manner.[31] On the other hand, a mosquito may have HIV-infected blood in its gut, and if swatted on the skin of a human who then scratches it, transmission is hypothetically possible,[32] though this risk is extremely small, and no cases have yet been identified through this route.

HIV survives for only a short time outside the body

HIV can survive at room temperature outside the body for hours if dry (provided that initial concentrations are high),[33] and for weeks if wet (in used syringes/needles).[34] However, the amounts typically present in bodily fluids do not survive nearly as long outside the body—generally no more than a few minutes if dry.[25]

HIV can infect only homosexual men and drug users

HIV can transmit from one person to another if an engaging partner is HIV positive. In the United States, the main route of infection is via homosexual anal sex, while for women transmission is primarily through heterosexual contact.[35] It is true that anal sex (regardless of the sex of the receptive partner) carries a higher risk of infection than most sex acts, but most penetrative sex acts between any individuals carry some risk. Properly used condoms can reduce this risk.[36]

An HIV-infected female cannot have children

HIV-infected women remain fertile, although in late stages of HIV disease a pregnant woman may have a higher risk of miscarriage. Normally, the risk of transmitting HIV to the unborn child is between 15 and 30%. However, this may be reduced to just 2–3% if patients carefully follow medical guidelines.[37][38]

HIV cannot be the cause of AIDS because the body develops a vigorous antibody response to the virus

This reasoning ignores numerous examples of viruses other than HIV that can be pathogenic after evidence of immunity appears. Measles virus may persist for years in brain cells, eventually causing a chronic neurologic disease despite the presence of antibodies. Viruses such as Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus, and Varicella zoster may be activated after years of latency even in the presence of abundant antibodies. In other animals, viral relatives of HIV with long and variable latency periods, such as visna virus in sheep, cause central nervous system damage even after the production of antibodies.[39]

HIV has a well-recognized capacity to mutate to evade the ongoing immune response of the host.[40]

Only a small number of CD4+ T-cells are infected by HIV, not enough to damage the immune system

Although the fraction of CD4+ T-cells that is infected with HIV at any given time is never high (only a small subset of activated cells serve as ideal targets of infection), several groups have shown that rapid cycles of death of infected cells and infection of new target cells occur throughout the course of the disease.[41] Macrophages and other cell types are also infected with HIV and serve as reservoirs for the virus.

Furthermore, like other viruses, HIV is able to suppress the immune system by secreting proteins that interfere with it. For example, HIV's coat protein, gp120, sheds from viral particles and binds to the CD4 receptors of otherwise healthy T-cells; this interferes with the normal function of these signalling receptors. Another HIV protein, Tat, has been demonstrated to suppress T cell activity.

Infected lymphocytes express the Fas ligand, a cell-surface protein that triggers the death of neighboring uninfected T-cells expressing the Fas receptor.[42] This "bystander killing" effect shows that great harm can be caused to the immune system even with a limited number of infected cells.

History of HIV/AIDS

The current consensus is that HIV was introduced to North America by a Haitian immigrant who contracted it while working in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 1960s, or from another person who worked there during that time.[43] In 1981 on June 5, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) describing cases of a rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), in five healthy gay men in Los Angeles. This edition would later become MMWR's first official reporting of the AIDS epidemic in North America.[44] By year-end, a cumulative total of 337 cases of severe immune deficiency had been reported, and 130 out of the 337 reported cases had died.[44] On September 24, 1982, the CDC used the term "AIDS" (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) for the first time, and released the first case definition of AIDS: "a disease at least moderately predictive of a defect in cell-mediated immunity, occurring in a person with no known case for diminished resistance to that disease."[44] The March 4, 1983 edition of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) noted that most cases of AIDS had been reported among homosexual men with multiple sexual partners, injection drug users, Haitians, and hemophiliacs. The report suggested that AIDS may be caused by an infectious agent that is transmitted sexually or through exposure to blood or blood products, and issued recommendations for preventing transmission.[44] Although most cases of HIV/AIDS were discovered in gay men, on January 7, 1983, the CDC reported cases of AIDS in female sexual partners of males with AIDS.[44] In 1984, scientists identified the virus that causes AIDS, which was first named after the T-cells affected by the strain and is now called HIV or human immunodeficiency virus.[45]

Origin of AIDS through human–monkey sexual intercourse

While HIV is most likely a mutated form of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a disease present only in chimpanzees and African monkeys, highly plausible explanations for the transfer of the disease between species (zoonosis) exist not involving sexual intercourse.[46] In particular, the African chimpanzees and monkeys which carry SIV are often hunted for food, and epidemiologists theorize that the disease may have appeared in humans after hunters came into blood-contact with monkeys infected with SIV that they had killed.[47] The first known instance of HIV in a human was found in a person who died in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1959,[48] and a recent study dates the last common ancestor of HIV and SIV to between 1884 and 1914 by using a molecular clock approach.[49]

Tennessee State Senator Stacey Campfield was the subject of controversy in 2012 after stating that AIDS was the result of a human having sexual intercourse with a monkey.[50][51]

Gaëtan Dugas as "patient zero"

The Canadian flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas has been referred to as "patient zero" of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, meaning the first case of HIV/AIDS in the United States. In fact, the "patient zero" moniker originated from a misinterpretation of a 1984 study[52] that referred to Dugas as "patient O", where the O stood for "out of California".[53][54] A 2016 study published in Nature found "neither biological nor historical evidence that [Dugas] was the primary case in the US or for subtype B as a whole."[55]

AIDS denialism

There is no AIDS in Africa, as AIDS is nothing more than a new name for old diseases

The diseases that have come to be associated with AIDS in Africa, such as cachexia, diarrheal diseases and tuberculosis have long been severe burdens there. However, high rates of mortality from these diseases, formerly confined to the elderly and malnourished, are now common among HIV-infected young and middle-aged people, including well-educated members of the middle class.[56]

For example, in a study in Côte d'Ivoire, HIV-seropositive individuals with pulmonary tuberculosis were 17 times more likely to die within six months than HIV-seronegative individuals with pulmonary tuberculosis.[57] In Malawi, mortality over three years among children who had received recommended childhood immunizations and who survived the first year of life was 9.5 times higher among HIV-seropositive children than among HIV-seronegative children. The leading causes of death were wasting and respiratory conditions.[58] Elsewhere in Africa, findings are similar.

HIV is not the cause of AIDS

There is broad scientific consensus that HIV is the cause of AIDS, but some individuals reject this consensus, including biologist Peter Duesberg, biochemist David Rasnick, journalist/activist Celia Farber, conservative writer Tom Bethell, and intelligent design advocate Phillip E. Johnson. (Some one-time skeptics have since rejected AIDS denialism, including physiologist Robert Root-Bernstein, and physician and AIDS researcher Joseph Sonnabend.)

A great deal is known about the pathogenesis of HIV disease, even though important details remain to be elucidated. However, a complete understanding of the pathogenesis of a disease is not a prerequisite to knowing its cause. Most infectious agents have been associated with the disease they cause long before their pathogenic mechanisms have been discovered. Because research in pathogenesis is difficult when precise animal models are unavailable, the disease-causing mechanisms in many diseases, including tuberculosis and hepatitis B, are poorly understood, but the pathogens responsible are very well established.[4]

AZT and other antiretroviral drugs, not HIV, cause AIDS

The vast majority of people with AIDS never received antiretroviral drugs, including those in developed countries prior to the licensure of AZT in 1987. Even today, very few individuals in developing countries have access to these medications.[59]

In the 1980s, clinical trials enrolling patients with AIDS found that AZT given as single-drug therapy conferred a survival advantage compared to placebo, albeit modest and short-lived. Among HIV-infected patients who had not yet developed AIDS, placebo-controlled trials found that AZT given as a single-drug therapy delayed, for a year or two, the onset of AIDS-related illnesses. The lack of excess AIDS cases and death in the AZT arms of these placebo-controlled trials effectively counters the argument that AZT causes AIDS.[39]

Subsequent clinical trials found that patients receiving two-drug combinations had up to 50% increases in time to progression to AIDS and in survival when compared to people receiving single-drug therapy. In more recent years, three-drug combination therapies have produced another 50–80% improvements in progression to AIDS and in survival when compared to two-drug regimens in clinical trials.[60] Use of potent anti-HIV combination therapies has contributed to dramatic reductions in the incidence of AIDS and AIDS-related deaths in populations where these drugs are widely available, an effect which would be unlikely if antiretroviral drugs caused AIDS.[61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70]

Behavioral factors such as recreational drug use and multiple sexual partners—not HIV—account for AIDS

The proposed behavioral causes of AIDS, such as multiple sexual partners and long-term recreational drug use, have existed for many years. The epidemic of AIDS, characterized by the occurrence of formerly rare opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), did not occur in the United States until a previously unknown human retrovirus—HIV—spread through certain communities.[71]

Compelling evidence against the hypothesis that behavioral factors cause AIDS comes from recent studies that have followed cohorts of homosexual men for long periods of time and found that only HIV-seropositive men develop AIDS. For example, in a prospectively studied cohort in Vancouver, British Columbia, 715 homosexual men were followed for a median of 8.6 years. Among 365 HIV-positive individuals, 136 developed AIDS. No AIDS-defining illnesses occurred among 350 seronegative men, despite the fact that these men reported appreciable use of nitrite inhalants ("poppers") and other recreational drugs, and frequent receptive anal intercourse (Schechter et al., 1993).[72]

Other studies show that among homosexual men and injection-drug users, the specific immune deficit that leads to AIDS—a progressive and sustained loss of CD4+ T-cells—is extremely rare in the absence of other immunosuppressive conditions. For example, in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, more than 22,000 T-cell determinations in 2,713 HIV-seronegative homosexual men revealed only one individual with a CD4+ T-cell count persistently lower than 300 cells/µl of blood, and this individual was receiving immunosuppressive therapy.[73]

In a survey of 229 HIV-seronegative injection-drug users in New York City, mean CD4+ T-cell counts of the group were consistently more than 1000 cells/µl of blood. Only two individuals had two CD4+ T-cell measurements of less than 300/µl of blood, one of whom died with cardiac disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma listed as the cause of death.[74]

AIDS among transfusion recipients is due to underlying diseases that necessitated the transfusion, rather than to HIV

This notion is contradicted by a report by the Transfusion Safety Study Group (TSSG), which compared HIV-negative and HIV-positive blood recipients who had been given blood transfusions for similar diseases. Approximately 3 years following blood transfusion, the mean CD4+ T-cell count in 64 HIV-negative recipients was 850/µl of blood, while 111 HIV-seropositive individuals had average CD4+ T-cell counts of 375/µl of blood. By 1993, there were 37 cases of AIDS in the HIV-infected group, but not a single AIDS-defining illness in the HIV-seronegative transfusion recipients.[75][76]

High usage of clotting factor concentrate, not HIV, leads to CD4+ T-cell depletion and AIDS in hemophiliacs

This view is contradicted by many studies. For example, among HIV-seronegative patients with hemophilia A enrolled in the Transfusion Safety Study, no significant differences in CD4+ T-cell counts were noted between 79 patients with no or minimal factor treatment and 52 with the largest amount of lifetime treatments. Patients in both groups had CD4+ T-cell-counts within the normal range.[77] In another report from the Transfusion Safety Study, no instances of AIDS-defining illnesses were seen among 402 HIV-seronegative hemophiliacs who had received factortherapy.[78]

In a cohort in the United Kingdom, researchers matched 17 HIV-seropositive hemophiliacs with 17 HIV-seronegative hemophiliacs with regard to clotting factor concentrate usage over a ten-year period. During this time, 16 AIDS-defining clinical events occurred in 9 patients, all of whom were HIV-seropositive. No AIDS-defining illnesses occurred among the HIV-negative patients. In each pair, the mean CD4+ T-cell count during follow-up was, on average, 500 cells/µl lower in the HIV-seropositive patient.[79]

Among HIV-infected hemophiliacs, Transfusion Safety Study investigators found that neither the purity nor the amount of factor VIII therapy had a deleterious effect on CD4+ T-cell counts.[80] Similarly, the Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study found no association between the cumulative dose of plasma concentrate and incidence of AIDS among HIV-infected hemophiliacs.[81]

The distribution of AIDS cases casts doubt on HIV as the cause. Viruses are not gender-specific, yet only a small proportion of AIDS cases are among women

The distribution of AIDS cases, whether in the United States or elsewhere in the world, invariably mirrors the prevalence of HIV in a population. In the United States, HIV first appeared in populations of injection-drug users (a majority of whom are male) and gay men. HIV is spread primarily through unprotected sex, the exchange of HIV-contaminated needles, or cross-contamination of the drug solution and infected blood during intravenous drug use. Because these behaviors show a gender skew—Western men are more likely to take illegal drugs intravenously than Western women, and men are more likely to report higher levels of the riskiest sexual behaviors, such as unprotected anal intercourse—it is not surprising that a majority of U.S. AIDS cases have occurred in men.[82]

Women in the United States, however, are increasingly becoming HIV-infected, usually through the exchange of HIV-contaminated needles or sex with an HIV-infected male. The CDC estimates that 30 percent of new HIV infections in the United States in 1998 were in women. As the number of HIV-infected women has risen, so too has the number of female AIDS patients in the United States. Approximately 23% of U.S. adult/adolescent AIDS cases reported to the CDC in 1998 were among women. In 1998, AIDS was the fifth leading cause of death among women aged 25 to 44 in the United States, and the third leading cause of death among African-American women in that age group.[83]

In Africa, HIV was first recognized in sexually active heterosexuals, and AIDS cases in Africa have occurred at least as frequently in women as in men. Overall, the worldwide distribution of HIV infection and AIDS between men and women is approximately 1 to 1.[84] In sub-Saharan Africa, 57% of adults with HIV are women, and young women aged 15 to 24 are more than three times as likely to be infected as young men.[85]

HIV is not the cause of AIDS because many individuals with HIV have not developed AIDS

HIV infections have a prolonged and variable course. The median period of time between infection with HIV and the onset of clinically apparent disease is approximately 10 years in industrialized countries, according to prospective studies of homosexual men in which dates of seroconversion are known. Similar estimates of asymptomatic periods have been made for HIV-infected blood-transfusion recipients, injection-drug users and adult hemophiliacs.[86]

As with many diseases, a number of factors can influence the course of HIV disease. Factors such as age or genetic differences between individuals, the level of virulence of the individual strain of virus, as well as exogenous influences such as co-infection with other microbes may determine the rate and severity of HIV disease expression. Similarly, some people infected with hepatitis B, for example, show no symptoms or only jaundice and clear their infection, while others suffer disease ranging from chronic liver inflammation to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Co-factors probably also determine why some smokers develop lung cancer while others do not.[40][87][88]

HIV is not the cause of AIDS because some people have symptoms associated with AIDS but are not infected with HIV

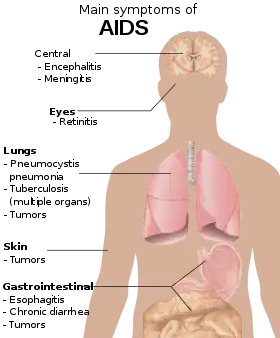

Most AIDS symptoms result from the development of opportunistic infections and cancers associated with severe immunosuppression secondary to HIV.

However, immunosuppression has many other potential causes. Individuals who take glucocorticoids or immunosuppressive drugs to prevent transplant rejection or to treat autoimmune diseases can have increased susceptibility to unusual infections, as do individuals with certain genetic conditions, severe malnutrition and certain kinds of cancers. There is no evidence suggesting that the numbers of such cases have risen, while abundant epidemiologic evidence shows a very large rise in cases of immunosuppression among individuals who share one characteristic: HIV infection.[39][56]

The spectrum of AIDS-related infections seen in different populations proves that AIDS is actually many diseases not caused by HIV

The diseases associated with AIDS, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP) and Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), are not caused by HIV, but rather result from the immunosuppression caused by HIV disease. As the immune system of an HIV-infected individual weakens, he or she becomes susceptible to the particular viral, fungal, and bacterial infections common in the community. For example, HIV-infected people in the Midwestern United States are much more likely than people in New York City to develop histoplasmosis, which is caused by a fungus. A person in Africa is exposed to pathogens different from individuals in an American city. Children may be exposed to different infectious agents compared to adults.[89]

HIV is the underlying cause of the condition named AIDS, but the additional conditions that may affect an AIDS patient are dependent upon the endemic pathogens to which the patient may be exposed.

AIDS can be prevented with complementary or alternative medicine

Many HIV-infected people turn to complementary and alternative medicine, such as traditional medicine, especially in areas where conventional therapies are less widespread.[90] However, the overwhelming majority of scientifically rigorous research indicates little or negative effect on patient outcomes such as HIV-symptom severity and disease duration, and mixed outcomes on psychological well-being.[91][92] It is important that patients notify their healthcare provider prior to beginning any treatment, as certain alternative therapies may interfere with conventional treatment.[93][94]

See also

- International AIDS Society

- Safe sex

- Contaminated haemophilia blood products

- Prevention of HIV/AIDS

References

- ↑ Kallings LO (2008). "The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS". Journal of Internal Medicine. 263 (3): 218–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01910.x. PMID 18205765.

- ↑ "AIDS epidemic update" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ "HIV vs. AIDS: What's the Difference?". Healthline. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- 1 2 "The Evidence that HIV Causes AIDS". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. 4 September 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "HIV vs. AIDS: What's the Difference?". Healthline. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ↑ "Children and HIV and AIDS – What is the relationship between HIV and AIDS and emergencies?". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ↑ Becker, S.; Dezii, C.M.; Burtcel, B.; Kawabata, H.; Hodder, S. (2002). "Young HIV-infected adults are at greater risk for medication nonadherence". Medscape General Medicine. 4 (3): 21. PMID 12466764.

- ↑ Fan, H.; Conner, R.F.; Villarreal, L.P., eds. (2005). AIDS: science and society (4th ed.). Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-0086-7.

- ↑ "HIV Undetectable=Untransmittable (U=U), or Treatment as Prevention | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Eshleman, Susan H.; Wilson, Ethan A.; Zhang, Xinyi C.; Ou, San-San; Piwowar-Manning, Estelle; Eron, Joseph J.; McCauley, Marybeth; Gamble, Theresa; Gallant, Joel E.; Hosseinipour, Mina C.; Kumarasamy, Nagalingeswaran; Hakim, James G.; Kalonga, Ben; Pilotto, Jose H.; Grinsztejn, Beatriz; Godbole, Sheela V.; Chotirosniramit, Nuntisa; Santos, Breno Riegel; Shava, Emily; Mills, Lisa A.; Panchia, Ravindre; Mwelase, Noluthando; Mayer, Kenneth H.; Chen, Ying Q.; Cohen, Myron S.; Fogel, Jessica M. (May 2017). "Virologic outcomes in early antiretroviral treatment: HPTN 052". HIV Clinical Trials. 18 (3): 100–109. doi:10.1080/15284336.2017.1311056. PMC 5633001. PMID 28385131.

- 1 2 Flanagan, Jane (2001-11-11). "South African men rape babies as 'cure' for Aids". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- 1 2 Meel, B.L. (2003). "1. The myth of child rape as a cure for HIV/AIDS in Transkei: a case report". Med. Sci. Law. 43 (1): 85–88. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.43.1.85. PMID 12627683. S2CID 2706882. Archived from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Groce, N.E.; Trasi, R. (2004). "Rape of individuals with disability: AIDS and the folk belief of virgin cleansing". Lancet. 363 (9422): 1663–64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16288-0. PMID 15158626. S2CID 34857351.

- ↑ "Bestiality new Aids myth – SPCA" Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, March 25, 2002; retrieved February 22, 2007

- ↑ ""HIV Assays: Operational Characteristics", World Health Organization, 2004" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Gilbert, Mark; Krajden, Mel (July–August 2010). "Don't wait to test for HIV". BC Medical Journal. 52 (6): 308.

- ↑ Jackson, J.B.; Kwok, S.Y.; Sninsky, J.J.; Hopsicker, J.S.; Sannerud, K.J.; Rhame, F.S.; Henry, K.; Simpson, M.; Balfour, H.H. Jr; et al. (1990). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 detected in all seropositive symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals". J. Clin. Microbiol. 28 (1): 16–19. doi:10.1128/JCM.28.1.16-19.1990. PMC 269529. PMID 2298875.

- ↑ Busch, M.P.; Eble, B.E.; Khayam-Bashi, H.; Heilbron, D.; Murphy, E.L.; Kwok, S.; Sninsky, J.; Perkins, H.A.; Vyas, G.N.; et al. (1991). "Evaluation of screened blood donations for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by culture and DNA amplification of pooled cells". N. Engl. J. Med. 325 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199107043250101. PMID 2046708.

- ↑ Silvester, C.; Healey, D.S.; Cunningham, P.; Dax, E.M. (1995). "Multisite evaluation of four anti-HIV-1/HIV-2 enzyme immunoassays. Australian HIV Test Evaluation Group". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 8 (4): 411–19. doi:10.1097/00042560-199504000-00014. PMID 7882108.

- ↑ Urassa, W.; Godoy, K.; Killewo, J.; Kwesigabo, G.; Mbakileki, A.; Mhalu, F.; Biberfeld, G. (1999). "The accuracy of an alternative confirmatory strategy for detection of antibodies to HIV-1: experience from a regional laboratory in Kagera, Tanzania". J. Clin. Virol. 14 (1): 25–29. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(99)00043-8. PMID 10548127.

- ↑ Nkengasong, J.N.; Maurice, C.; Koblavi, S.; Kalou, M.; Yavo, D.; Maran, M.; Bile, C.; N'guessan, K.; Kouadio, J.; et al. (1999). "Evaluation of HIV serial and parallel serologic testing algorithms in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire". AIDS. 13 (1): 109–17. doi:10.1097/00002030-199901140-00015. PMID 10207552.

- ↑ Samdal, H.H.; Gutigard, B.G.; Labay, D.; Wiik, S.I.; Skaug, K.; Skar, A.G. (1996). "Comparison of the sensitivity of four rapid assays for the detection of antibodies to HIV-1/HIV-2 during seroconversion". Clin. Diagn. Virol. 7 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1016/S0928-0197(96)00244-9. PMID 9077430.

- ↑ Madhok, R.; Gracie, J.A.; Lowe, G.D.; Forbes, C.D. (1986). "Lack of HIV transmission by casual contact". Lancet. 328 (8511): 863. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92898-9. PMID 2876307. S2CID 28722212.

- ↑ Courville, T.M.; Caldwell, B.; Brunell, P.A. (1998). "Lack of evidence of transmission of HIV-1 to family contacts of HIV-1 infected children". Clin. Pediatr. 37 (3): 175–78. doi:10.1177/000992289803700303. PMID 9545605. S2CID 30065399.

- 1 2 ""Kissing and HIV"". Archived from the original on 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ "THT: "Ways HIV is not passed on"". Archived from the original on 2015-06-01. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ↑ Bartholomew, Courtenay F; Jones, Avion M (2006). "Human bites: a rare risk factor for HIV transmission". AIDS. 20 (4): 631–32. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000210621.13825.75. PMID 16470132.

- ↑ Piya Sorcar (March 2009). "Teaching Taboo Topics Without Talking About Them: An Epistemic Study of a New Approach to HIV/AIDS Prevention Education in India" (PDF). Stanford University, TeachAids. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-24. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Yu, M; Vajdy, M (August 2010). "Mucosal HIV transmission and vaccination strategies through oral compared with vaginal and rectal routes". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 10 (8): 1181–95. doi:10.1517/14712598.2010.496776. PMC 2904634. PMID 20624114.

- ↑ Patel, Pragna; Borkowf, Craig B.; Brooks, John T.; Lasry, Arielle; Lansky, Amy; Mermin, Jonathan (2014-06-19). "Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review". AIDS. 28 (10): 1509–1519. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000298. ISSN 0269-9370. PMC 6195215. PMID 24809629.

- ↑ Webb, P.A.; Happ, C.M.; Maupin, G.O.; Johnson, B.J.; Ou, C.Y.; Monath, T.P. (1989). "Potential for insect transmission of HIV: experimental exposure of Cimex hemipterus and Toxorhynchites amboinensis to human immunodeficiency virus". J. Infect. Dis. 160 (6): 970–77. doi:10.1093/infdis/160.6.970. PMID 2479697.

- ↑ Siemens, D.F. (1987). "AIDS Transmission and Insects". Science. 238 (4824): 143. Bibcode:1987Sci...238..143S. doi:10.1126/science.2889266. PMID 2889266.

- ↑ Resnick, L.; Veren, K.; Salahuddin, S.Z.; Tondreau, S.; Markham, P.D. (1986). "Stability and inactivation of HTLV-III/LAV under clinical and laboratory environments". JAMA. 255 (14): 1887–91. doi:10.1001/jama.255.14.1887. PMID 2419594.

- ↑ Heimer, R.; Abdala, N. (2000). "Viability of HIV-1 in syringes: implications for interventions among injection drug users". AIDS Reader. 10 (7): 410–17. PMID 10932845.

- ↑ "HIV Surveillance –Epidemiology of HIV Infection (through 2008)". Center for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ "Condoms and STDs: Fact Sheet for Public Health Personnel". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ↑ Groginsky, E.; Bowdler, N.; Yankowitz, J. (1998). "Update on vertical HIV transmission". J Reprod Med. 43 (8): 637–46. PMID 9749412.

- ↑ WHO, 2005

- 1 2 3 "Disease Progression Despite Antibodies", "The Relationship Between the Human Immunodeficiency Virus and the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome", National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, September, 1995

- 1 2 Levy, J.A. (1993). "Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection". Microbiol. Rev. 57 (1): 183–289. Bibcode:1989NYASA.567...58L. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb16459.x. PMC 372905. PMID 8464405.

- ↑ Richman, D.D. (2000). "Normal physiology and HIV pathophysiology of human T-cell dynamics". J. Clin. Invest. 105 (5): 565–66. doi:10.1172/JCI9478. PMC 292457. PMID 10712427.

- ↑ Xu, X.N.; Laffert, B.; Screaton, G.R.; Kraft, M.; Wolf, D.; Kolanus, W.; Mongkolsapay, J.; McMichael, A.J.; Baur, A.S.; et al. (1999). "Induction of Fas ligand expression by HIV involves the interaction of Nef with the T cell receptor zeta chain". J. Exp. Med. 189 (9): 1489–96. doi:10.1084/jem.189.9.1489. PMC 2193060. PMID 10224289.

- ↑ "Key HIV strain 'came from Haiti'". BBC News. 2007-10-30. Archived from the original on 2012-05-21. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Timeline of HIV and AIDS". HIV.gov. 2016-05-11. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Wilson, Jacque Wilson. "Timeline: AIDS moments to remember". CNN. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ↑ Locatelli, S; Peeters, M (Mar 27, 2012). "Cross-species transmission of simian retroviruses: how and why they could lead to the emergence of new diseases in the human population". AIDS. 26 (6): 659–73. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328350fb68. PMID 22441170. S2CID 38760788.

- ↑ Sharp, PM; Hahn, BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS Pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ↑ Zhu, T.; Korber, B.T.; Nahmias, A.J.; Hooper, E.; Sharp, P.M.; Ho, D.D. (1998). "An African HIV-1 sequence from 1959 and implications for the origin of the epidemic". Nature. 391 (6667): 594–97. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..594Z. doi:10.1038/35400. PMID 9468138. S2CID 4416837.

- ↑ Worobey, Michael; Gemmel, Marlea; et al. (2 October 2008). "Direct evidence of extensive diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960". Nature. 455 (7293): 661–64. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..661W. doi:10.1038/nature07390. PMC 3682493. PMID 18833279. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ↑ Signorile, Michelangelo (2012-01-26). "Stacey Campfield, Tennessee Senator Behind 'Don't Say Gay' Bill, On Bullying, AIDS And Homosexual 'Glorification'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ "Knoxville Republican says AIDS came from man having sex with a monkey then with other men". Politifact. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Auerbach, D.M.; W.W. Darrow; H.W. Jaffe; J.W. Curran (1984). "Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Patients linked by sexual contact". The American Journal of Medicine. 76 (3): 487–92. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90668-5. PMID 6608269.

- ↑ Johnson, Brian D. (17 April 2019). "How a typo created a scapegoat for the AIDS epidemic". Maclean's. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ↑ "Researchers Clear 'Patient Zero' From AIDS Origin Story". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Worobey, Michael; Thomas D. Watts; et al. (October 26, 2016). "1970s and 'Patient 0' HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America". Nature. 539 (7627): 98–101. Bibcode:2016Natur.539...98W. doi:10.1038/nature19827. PMC 5257289. PMID 27783600.

- 1 2 UNAIDS, 2000

- ↑ Ackah, A.N.; Coulibaly, D.; Digbeu, H.; Diallo, K.; Vetter, K.M.; Coulibaly, I.M.; Greenberg, A.E.; De Cock, K.M. (1995). "Response to treatment, mortality, and CD4 lymphocyte counts in HIV-infected persons with tuberculosis in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire". Lancet. 345 (8950): 607–10. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90519-7. PMID 7898177. S2CID 19384981.

- ↑ Taha, T.E.; Kumwenda, N.I.; Broadhead, R.L.; Hoover, D.R.; Graham, S.M.; Van Der, Hoven L.; Markakis, D.; Liomba, G.N.; Chiphangwi, J.D.; et al. (1999). "Mortality after the first year of life among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected children". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18 (8): 689–94. doi:10.1097/00006454-199908000-00007. PMID 10462337.

- ↑ UNAIDS, 2003 Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "HHS, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2005-08-23.

- ↑ Palella, F.J. Jr; Delaney, K.M.; Moorman, A.C.; Loveless, M.O.; Fuhrer, J.; Satten, G.A.; Aschman, D.J.; Holmberg, S.D. (1998). "Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (13): 853–60. doi:10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. PMID 9516219.

- ↑ Mocroft, A.; Vella, S.; Benfield, T.L.; Chiesi, A.; Miller, V.; Gargalianos, P.; Arminio Monforte, A.; Yust, I.; Bruun, J.N.; et al. (1998). "Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. EuroSIDA Study Group". Lancet. 352 (9142): 1725–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03201-2. PMID 9848347. S2CID 32223916.

- ↑ Mocroft, A.; Katlama, C.; Johnson, A.M.; Pradier, C.; Antunes, F.; Mulcahy, F.; Chiesi, A.; Phillips, A.N.; Kirk, O.; et al. (2000). "AIDS across Europe, 1994–98: the EuroSIDA study". Lancet. 356 (9226): 291–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02504-6. PMID 11071184. S2CID 8167162.

- ↑ Vittinghoff, E.; Scheer, S.; O'Malley, P.; Colfax, G.; Holmberg, S.D.; Buchbinder, S.P. (1999). "Combination antiretroviral therapy and recent declines in AIDS incidence and mortality". J. Infect. Dis. 179 (3): 717–20. doi:10.1086/314623. PMID 9952385.

- ↑ Detels, R.; Munoz, A.; McFarlane, G.; Kingsley, L.A.; Margolick, J.B.; Giorgi, J.; Schrager, L.K.; Phair, J.P. (1998). "Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators". JAMA. 280 (17): 1497–503. doi:10.1001/jama.280.17.1497. PMID 9809730.

- ↑ De Martino, M; Tovo, PA; Balducci, M; Galli, L; Gabiano, C; Rezza, G; Pezzotti, P (2000). "Reduction in mortality with availability of antiretroviral therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. Italian Register for HIV Infection in Children and the Italian National AIDS Registry". JAMA. 284 (2): 190–97. doi:10.1001/jama.284.2.190. PMID 10889592.

- ↑ Hogg, R.S.; Yip, B.; Kully, C.; Craib, K.J.; O'Shaughnessy, M.V.; Schechter, M.T.; Montaner, J.S. (1999). "Improved survival among HIV-infected patients after initiation of triple-drug antiretroviral regimens". CMAJ. 160 (5): 659–65. PMC 1230111. PMID 10102000.

- ↑ Schwarcz, S.K.; Hsu, L.C.; Vittinghoff, E.; Katz, M.H. (2000). "Impact of protease inhibitors and other antiretroviral treatments on acquired immunodeficiency syndrome survival in San Francisco, California, 1987–1996". Am. J. Epidemiol. 152 (2): 178–85. doi:10.1093/aje/152.2.178. PMID 10909955.

- ↑ Kaplan, JE; Hanson, D; Dworkin, MS; Frederick, T; Bertolli, J; Lindegren, ML; Holmberg, S; Jones, JL (2000). "Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus-associated opportunistic infections in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 30 Suppl 1: S5–S14. doi:10.1086/313843. PMID 10770911.

- ↑ McNaghten, A.D.; Hanson, D.L.; Jones, J.L.; Dworkin, M.S.; Ward, J.W.; The Adultadolescent Spectrum Of Disease Group +/ (1999). "Effects of antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic illness primary chemoprophylaxis on survival after AIDS diagnosis. Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of Disease Group". AIDS. 13 (13): 1687–95. doi:10.1097/00002030-199909100-00012. PMID 10509570.

- ↑ "NIAID". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Schechter, M.T.; Craib, K.J.; Gelmon, K.A.; Montaner, J.S.; Le, T.N.; O'Shaughnessy, M.V.; Schechter, M.T.; Gelmon, K.A.; Montaner, J.S.G. (1993). "HIV-1 and the aetiology of AIDS". Lancet. 341 (8846): 658–59. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)90421-C. PMID 8095571. S2CID 23141531.

- ↑ Vermund, S.H.; Hoover, D.R.; Chen, K. (1993). "CD4+ counts in seronegative homosexual men. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study". N. Engl. J. Med. 328 (6): 442. doi:10.1056/NEJM199302113280615. PMID 8093639.

- ↑ Des Jarlais, D.C.; Friedman, S.R.; Marmor, M.; Mildvan, D.; Yancovitz, S.; Sotheran, J.L.; Wenston, J.; Beatrice, S. (1993). "CD4 lymphocytopenia among injecting drug users in New York City". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6 (7): 820–22. PMID 8099613.

- ↑ Donegan, E.; Stuart, M.; Niland, J.C.; Sacks, H.S.; Azen, S.P.; Dietrich, S.L.; Faucett, C.; Fletcher, M.A.; Kleinman, S.H.; et al. (1990). "Infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) among recipients of antibody-positive blood donations". Annals of Internal Medicine. 113 (10): 733–39. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-733. PMID 2240875.

- ↑ Cohen, J. (1994). "Duesberg and critics agree: hemophilia is the best test". Science. 266 (5191): 1645–46. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1645C. doi:10.1126/science.7992044. PMID 7992044.

- ↑ Hassett, J.; Gjerset, G.F.; Mosley, J.W.; Fletcher, M.A.; Donegan, E.; Parker, J.W.; Counts, R.B.; Aledort, L.M.; Lee, H.; et al. (1993). "Effect on lymphocyte subsets of clotting factor therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-1-negative congenital clotting disorders. The Transfusion Safety Study Group". Blood. 82 (4): 1351–57. doi:10.1182/blood.V82.4.1351.1351. PMID 8353293.

- ↑ Aledort, L.M.; Operskalski, E.A.; Dietrich, S.L.; Koerper, M.A.; Gjerset, G.F.; Lusher, J.M.; Lian, E.C.; Mosley, J.W. (1993). "Low CD4+ counts in a study of transfusion safety. The Transfusion Safety Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 328 (6): 441–42. doi:10.1056/NEJM199302113280614. PMID 8093638.

- ↑ Sabin, C.A.; Pasi, K.J.; Phillips, A.N.; Lilley, P.; Bofill, M.; Lee, C.A. (1996). "Comparison of immunodeficiency and AIDS defining conditions in HIV negative and HIV positive men with haemophilia A". BMJ. 312 (7025): 207–10. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7025.207. PMC 2349998. PMID 8563582.

- ↑ Gjerset, G.F.; Pike, M.C.; Mosley, J.W.; Hassett, J.; Fletcher, M.A.; Donegan, E.; Parker, J.W.; Counts, R.B.; Zhou, Y.; et al. (1994). "Effect of low- and intermediate-purity clotting factor therapy on progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection in congenital clotting disorders. Transfusion Safety Study Group". Blood. 84 (5): 1666–71. doi:10.1182/blood.V84.5.1666.1666. PMID 7915149.

- ↑ Goedert, JJ; Kessler, CM; Aledort, LM; Biggar, RJ; Andes, WA; White Gc, 2nd; Drummond, JE; Vaidya, K; et al. (1989). "A prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and the development of AIDS in subjects with hemophilia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (17): 1141–48. doi:10.1056/NEJM198910263211701. PMID 2477702.

- ↑ "U.S. Census Bureau". Archived from the original on 2012-08-19. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ "AIDS/HIV Statics". Archived from the original on 2009-01-17. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ "U.S. Bureau Census". Archived from the original on 2012-08-19. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ "UNAIDS, 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Alcabes, P.; Munoz, A.; Vlahov, D.; Friedland, G.H. (1993). "Incubation period of human immunodeficiency virus". Epidemiol. Rev. 15 (2): 303–18. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036122. PMID 8174659.

- ↑ Evans, A.S. (1982). "The clinical illness promotion factor: a third ingredient". Yale J. Biol. Med. 55 (3–4): 193–99. PMC 2596440. PMID 6295003.

- ↑ Fauci, A.S. (1996). "Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease". Nature. 384 (6609): 529–34. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..529F. doi:10.1038/384529a0. PMID 8955267. S2CID 4370482. Archived from the original on 2023-04-04. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ "USPHS/IDSA". Archived from the original on 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Littlewood, RA; Vanable, PA (8 Dec 2011). "A global perspective on complementary and alternative medicine use among people living with HIV/AIDS in the era of antiretroviral treatment". Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 8 (4): 257–68. doi:10.1007/s11904-011-0090-8. PMID 21822625. S2CID 20186700.

- ↑ Mills, Edward; Wu, Ping; Ernst, Edzard (June 2005). "Complementary therapies for the treatment of HIV: in search of the evidence". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 16 (6): 395–403. doi:10.1258/0956462054093962. PMID 15969772. S2CID 7411052. Archived from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ↑ Littlewood, Rae A; Vandable, Peter A (June 2002). "Complementary and alternative medicine use among HIV-positive people: research synthesis and implications for HIV care". AIDS Care. 20 (8): 1002–18. doi:10.1080/09540120701767216. PMC 2570227. PMID 18608078.

- ↑ Piscitelli, Stephen C; Burstein, Aaron H; Chaitt, Doreen; Alfaro, Raul; Falloon, Judith (14 April 2001). "Indinavir concentrations and St John's wort". The Lancet. 355 (9203): 547–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05712-8. PMID 10683007. S2CID 7339081.

- ↑ Piscitelli, Stephen; Burstein, Aaron H.; Weldon, Nada; Gallicano, Keith D.; Falloon, Judith (Jan 2002). "The Effect of Garlic Supplements on the Pharmacokinetics of Saquinavir". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 34 (2): 234–38. doi:10.1086/324351. PMID 11740713.

External links

- HIV.gov – The U.S. Federal Domestic HIV/AIDS Resource Archived 2022-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- HIV Basics Archived 2019-03-30 at the Wayback Machine at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

.jpg.webp)