Oligoclonal band

Oligoclonal bands (OCBs) are bands of immunoglobulins that are seen when a patient's blood serum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is analyzed. They are used in the diagnosis of various neurological and blood diseases, especially in multiple sclerosis.

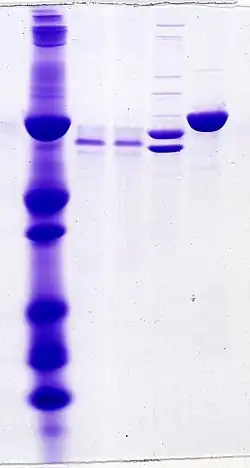

Two methods of analysis are possible: (a) protein electrophoresis, a method of analyzing the composition of fluids, also known as "agarose gel electrophoresis/Coomassie blue staining", and (b) the combination of isoelectric focusing/silver staining. The latter is more sensitive.[1]

For the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid, a patient has a lumbar puncture performed, which collects some of his or her cerebrospinal fluid. The blood serum can be gained from a clotted blood sample. Normally it is assumed that all the proteins that appear in the CSF, but are not present in the serum, are produced intrathecally (inside the CNS). Therefore, it is normal to subtract bands in serum from bands in CSF when investigating CNS diseases.

Oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis

OCBs are especially important for multiple sclerosis (MS). In MS, normally only OCBs made of immunoglobulin G antibodies are considered, though sometimes other proteins can be taken into account, like lipid-specific immunoglobulin M.[2][3] The presence of these IgM OCBs is associated with a more severe course.[4]

Typically for an OCB analysis, the CSF is concentrated and the serum is diluted. After this dilution/concentration prealbumin appears as higher on CSF. Albumin is typically the dominant band on both fluids. Transferrin is another prominent protein on CSF column because its small molecular size easily increases its filtration in to CSF. CSF has a relatively higher concentration of prealbumin than does serum. As expected large molecular proteins are absent in CSF column. After all these bands are localized, OCBs should be assessed in the γ region which normally hosts small group of polyclonal immunoglobulins.[5]

New techniques like "capillary isoelectric focusing immunoassay" are able to detect IgG OCBs in more than 95% of multiple sclerosis patients.[6]

Even more than 12 OCBs can appear in MS.[7] Each one of them represent antibody proteins (or protein fragments) secreted by plasma cells, although why exactly these bands are present, and which proteins these bands represent, has not yet been fully elucidated. The target antigens for these antibodies are not easy to find because it requires to isolate a single kind of protein in each band, though new techniques are able to do so.[8]

In 40% of MS patients with OCBs, antibodies specific to the viruses HHV-6 and EBV have been found.[9]

HHV-6 specific OCBs have also been found in other demyelinating diseases.[10][11] A lytic protein of HHV-6A virus was identified as the target of HHV-6 specific oligoclonal bands.[12]

Though early theories assumed that the OCBs were somehow pathogenic autoantigens, recent research has shown that the IgG present in the OCBs are antibodies against debris, and therefore, OCBs seem to be just a secondary effect of MS.[13] Nevertheless, OCBs remain useful as a biomarker.

Diagnostic value in MS

Oligoclonal bands are an important indicator in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Up to 95% of all patients with multiple sclerosis have permanently observable oligoclonal bands[14] at least for those with European ancestry.[15] The last available reports in 2017 were pointing to a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 87% for differential diagnosis versus MS mimickers (specificity respect unselected population should be equal or higher).[16]

Other application for OCB's is as a tool to classify patients. It is known since long ago that OCB negative MS patients have a slower evolution. Some reports point that the underlying condition that causes the MS lesions in these patients is different. There are four pathological patterns of damage, and in the majority of patients with pattern II and III brain lesions oligoclonal bands are absent or only transiently present.[17]

Heterogeneity

It has been reported that oligoclonal bands are nearly absent in patients with pattern II and pattern III lesion types.[18]

Six groups of patients are usually separated, based on OCBs:[19]

- type 1, no bands in CSF and serum;

- type 2, oligoclonal IgG bands in CSF,

- type 3, oligoclonal bands in CSF and serum with additional bands in CSF;

- type 4, identical oligoclonal bands in CSF and serum,

- type 5, monoclonal bands in CSF and serum,

- type 6, presence of a single band limited to the CSF.

Type 2 and 3 indicate intrathecal synthesis, and the rest are considered as negative results (No MS).

Alternatives

The main importance of oligoclonal bands was to demonstrate the production of intrathecal immunoglobins (IgGs) for establishing a MS diagnosis. Currently alternative methods for detection of this intrathecal synthesis have been published, and therefore it has lost some of its importance in this area.

A specially interesting method are free light chains (FLC), specially the kappa-FLCs (kFLCs). Several authors have reported that the nephelometric and ELISA FLCs determination is comparable with OCBs as markers of IgG synthesis, and kFLCs behave even better than oligoclonal bands.[20]

Another alternative to oligoclonal bands for MS diagnosis is the MRZ-reaction (MRZR), a polyspecific antiviral immune response against the viruses of measles, rubella and zoster found in 1992.[21]

In some reports the MRZR showed a lower sensitivity than OCB (70% vs. 100%), but a higher specificity (92% vs. 69%) for MS.[21]

Bands in other diseases

The presence of one band (a monoclonal band) may be considered serious, such as lymphoproliferative disease, or may simply be normal—it must be interpreted in the context of each specific patient. More bands may reflect the presence of a disease.

Diseases associated

Oligoclonal bands are found in:

- Multiple sclerosis[22]

- Lyme disease[23]

- Neuromyelitis optica (Devic's disease)[24]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[25]

- Neurosarcoidosis[26]

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis[27]

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage[28]

- Syphilis[29]

- Primary central nervous system lymphoma[30]

- Sjögren's syndrome[31]

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Meningeal carcinomatosis[32]

- Multiple myeloma[33]

- Parry–Romberg syndrome

External links

- Oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis - The Medical School, Birmingham University

- Oligoclonal Bands in CSF - ClinLab Navigator

References

- ↑ Davenport RD, Keren DF (1988). "Oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluids: significance of corresponding bands in serum for diagnosis of multiple sclerosis". Clinical Chemistry. 34 (4): 764–5. doi:10.1093/clinchem/34.4.764. PMID 3359616.

- ↑ Álvarez-Cermeño JC, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Costa-Frossard L, Sainz de la Maza S, Villar LM, Rebolleda G (2016). "Intrathecal lipid-specific oligoclonal IgM synthesis associates with retinal axonal loss in multiple sclerosis". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 360: 41–44. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.11.030. PMID 26723970. S2CID 4724614.

- ↑ Villar Luis M.; et al. (2015). "Lipid-specific immunoglobulin M bands in cerebrospinal fluid are associated with a reduced risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy during treatment with natalizumab". Annals of Neurology. 77 (3): 447–457. doi:10.1002/ana.24345. PMID 25581547. S2CID 20377417.

- ↑ Ferraro D, et al. (2015). "Cerebrospinal fluid CXCL13 in clinically isolated syndrome patients: Association with oligoclonal IgM bands and prediction of Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis" (PDF). Neuroimmunology. 283: 64–69. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.04.011. hdl:11380/1118697. PMID 26004159. S2CID 41252743.

- ↑ McPherson, Richard A.; Pincus, Matthew R. (2017-04-05). Henry's clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. McPherson, Richard A.,, Pincus, Matthew R. (23rd ed.). St. Louis, Mo. ISBN 9780323413152. OCLC 949280055.

- ↑ Halbgebauer S, Huss A, Buttmann M, Steinacker P, Oeckl P, Brecht I, Weishaupt A, Tumani H, Otto M (2016). "Detection of intrathecal immunoglobulin G synthesis by capillary isoelectric focusing immunoassay in oligoclonal band negative multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 263 (5): 954–960. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8094-3. PMID 26995358. S2CID 25399433.

- ↑ Dalla Costa Gloria; et al. (2015). "Clinical significance of the number of oligoclonal bands in patients with clinically isolated syndromes". Neuroimmunology. 289: 62–67. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.10.009. PMID 26616872. S2CID 31729574.

- ↑ Brändle Simone M.; Obermeier Birgit; Senel Makbule; Bruder Jessica; Mentele Reinhard; Khademi Mohsen; Olsson Tomas; Tumani Hayrettin; Kristoferitsch Wolfgang; Lottspeich Friedrich; Wekerlef Hartmut; Hohlfeld Reinhard; Dornmair Klaus (2016). "Distinct oligoclonal band antibodies in multiple sclerosis recognize ubiquitous self-proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (28): 7864–7869. doi:10.1073/pnas.1522730113. PMC 4948369. PMID 27325759.

- ↑ Virtanen JO, Wohler J, Fenton K, Reich DS, Jacobson S (2014). "Oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis reactive against two herpesviruses and association with magnetic resonance imaging findings". Multiple Sclerosis. 20 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1177/1352458513490545. PMC 5001156. PMID 23722324.

- ↑ Virtanen JO, Pietiläinen-Nicklén J, Uotila L, Färkkilä M, Vaheri A, Koskiniemi M (2011). "Intrathecal human herpesvirus 6 antibodies in multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases presenting as oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 237 (1–2): 93–7. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.06.012. PMID 21767883. S2CID 206275179.

- ↑ Pietiläinen-Nicklén J, Virtanen JO, Uotila L, Salonen O, Färkkilä M, Koskiniemi M (2014). "HHV-6-positivity in diseases with demyelination". Journal of Clinical Virology. 61 (2): 216–9. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.07.006. PMID 25088617.

- ↑ Alenda R, Alvarez-Lafuente R, Costa-Frossard L, Arroyo R, Mirete S, Alvarez-Cermeño JC, Villar LM (2014). "Identification of the major HHV-6 antigen recognized by cerebrospinal fluid IgG in multiple sclerosis". European Journal of Neurology. 21 (8): 1096–101. doi:10.1111/ene.12435. PMID 24724742. S2CID 26091973. Lay summary – HHV-6 Foundation (April 29, 2014).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-date=(help) - ↑ Wingera RC, Zamvil SS (2016). "Antibodies in multiple sclerosis oligoclonal bands target debris". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (28): 7696–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609246113. PMC 4948325. PMID 27357674.

- ↑ Correale J, de los Milagros M, Molinas B (2002). "Oligoclonal bands and antibody responses in Multiple Sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 249 (4): 375–389. doi:10.1007/s004150200026. PMID 11967640. S2CID 21523820.

- ↑ Goris A, Pauwels I, Gustavsen MW, van Son B, Hilven K, Bos SD, Celius EG, Berg-Hansen P, Aarseth J, Myhr KM, D'Alfonso S, Barizzone N, Leone MA, Martinelli Boneschi F, Sorosina M, Liberatore G, Kockum I, Olsson T, Hillert J, Alfredsson L, Bedri SK, Hemmer B, Buck D, Berthele A, Knier B, Biberacher V, van Pesch V, Sindic C, Bang Oturai A, Søndergaard HB, Sellebjerg F, Jensen PE, Comabella M, Montalban X, Pérez-Boza J, Malhotra S, Lechner-Scott J, Broadley S, Slee M, Taylor B, Kermode AG, Gourraud PA, Sawcer SJ, Andreassen BK, Dubois B, Harbo HF (2015). "Genetic variants are major determinants of CSF antibody levels in multiple sclerosis". Brain. 138 (3): 632–43. doi:10.1093/brain/awu405. PMC 4408440. PMID 25616667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), Quote "OCBs are reported to be observed in 90–95% of patients in Northern Europe, and are composed predominantly of IgG" - ↑ Bernitsas E, Khan O, Razmjou S, Tselis A, Bao F, Caon C, Millis S, Seraji-Bozorgzad N (Jul 2017). "Cerebrospinal fluid humoral immunity in the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 12 (7): e0181431. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1281431B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181431. PMC 5519077. PMID 28727770.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jarius S, König FB, Metz I, Ruprecht K, Paul F, Brück W, Wildemann B (29 Aug 2017). "Pattern II and pattern III MS are entities distinct from pattern I MS: evidence from cerebrospinal fluid analysis". J Neuroinflammation. 14 (1): 171. doi:10.1186/s12974-017-0929-z. PMC 5576197. PMID 28851393.

- ↑ Jarius S, König FB, Metz I, Ruprecht K, Paul F, Brück W, Wildemann B (2017). "Pattern II and pattern III MS are entities distinct from pattern I MS: evidence from cerebrospinal fluid analysis". Journal of Neuroinflammation. 14 (1): 171. doi:10.1186/s12974-017-0929-z. PMC 5576197. PMID 28851393.

- ↑ Pinar Asli (2018). "Cerebrospinal fluid oligoclonal banding patterns and intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis: Data comparison from a wide patient group". Neurological Sciences and Neurophysiology. 35: 21–28. doi:10.5152/NSN.2018.10247.

- ↑ Fabio Duranti; Massimo Pieri; Rossella Zenobi; Diego Centonze; Fabio Buttari; Sergio Bernardini; Mariarita Dessi. "kFLC Index: a novel approach in early diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis". International Journal of Scientific Research. 4 (8). Archived from the original on 2016-08-28. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- 1 2 Hottenrott Tilman, Dersch Rick, Berger Benjamin, Rauer Sebastian, Eckenweiler Matthias, Huzly Daniela, Stich Oliver (2015). "The intrathecal, polyspecific antiviral immune response in neurosarcoidosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and autoimmune encephalitis compared to multiple sclerosis in a tertiary hospital cohort". Fluids Barriers CNS. 12: 27. doi:10.1186/s12987-015-0024-8. PMC 4677451. PMID 26652013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gilden, Donald H (March 2005). "Infectious causes of multiple sclerosis". The Lancet Neurology. 4 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01017-3. PMC 7129502. PMID 15721830.

- ↑ Hansen, K; Cruz, M; Link, H (June 1990). "Oligoclonal Borrelia burgdorferi-specific IgG antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid in Lyme neuroborreliosis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 161 (6): 1194–202. doi:10.1093/infdis/161.6.1194. PMID 2345300.

- ↑ Bergamaschi, R; Tonietti, S; Franciotta, D; Candeloro, E; Tavazzi, E; Piccolo, G; Romani, A; Cosi, V (2 July 2016). "Oligoclonal bands in Devic's neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: differences in repeated cerebrospinal fluid examinations". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 10 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1191/1352458504ms988oa. PMID 14760945. S2CID 11730134.

- ↑ Ernerudh, J; Olsson, T; Lindström, F; Skogh, T (August 1985). "Cerebrospinal fluid immunoglobulin abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 48 (8): 807–13. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.8.807. PMC 1028453. PMID 3875690.

- ↑ Lacomis, David (1 September 2011). "Neurosarcoidosis". Current Neuropharmacology. 9 (3): 429–436. doi:10.2174/157015911796557975. PMC 3151597. PMID 22379457.

- ↑ Mehta, PD; Patrick, BA; Thormar, H (November 1982). "Identification of virus-specific oligoclonal bands in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis by immunofixation after isoelectric focusing and peroxidase staining". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 16 (5): 985–7. doi:10.1128/jcm.16.5.985-987.1982. PMC 272519. PMID 6185532.

- ↑ Tsementzis, SA; Chao, SW; Hitchcock, ER; Gill, JS; Beevers, DG (March 1986). "Oligoclonal immunoglobulin G in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage and stroke". Neurology. 36 (3): 395–7. doi:10.1212/wnl.36.3.395. PMID 3951707. S2CID 42431540.

- ↑ Jones, HD; Urquhart, N; Mathias, RG; Banerjee, SN (1989). "An evaluation of oligoclonal banding and CSF IgG index in the diagnosis of neurosyphilis". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 17 (2): 75–9. doi:10.1097/00007435-199004000-00006. PMID 2193408. S2CID 36567041.

- ↑ Scott, Brian J.; Douglas, Vanja C.; Tihan, Tarik; Rubenstein, James L.; Josephson, S. Andrew (1 March 2013). "A Systematic Approach to the Diagnosis of Suspected Central Nervous System Lymphoma". JAMA Neurology. 70 (3): 311–9. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.606. PMC 4135394. PMID 23319132.

- ↑ Alexander, EL; Malinow, K; Lejewski, JE; Jerdan, MS; Provost, TT; Alexander, GE (March 1986). "Primary Sjögren's syndrome with central nervous system disease mimicking multiple sclerosis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 104 (3): 323–30. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-323. PMID 3946977.

- ↑ Duguid, JR; Layzer, R; Panitch, H (December 1983). "Oligoclonal bands in meningeal carcinomatosis". Archives of Neurology. 40 (13): 832. doi:10.1001/archneur.1983.04050120082023. PMID 6639419.

- ↑ Fujisawa, Manabu; Seike, Keisuke; Fukumoto, Kouta; Suehara, Yasuhito; Fukaya, Masafumi; Sugihara, Hiroki; Takeuchi, Masami; Matsue, Kosei (November 2014). "Oligoclonal bands in patients with multiple myeloma: Its emergence per se could not be translated to improved survival". Cancer Science. 105 (11): 1442–1446. doi:10.1111/cas.12527. PMC 4462372. PMID 25182124.