Nivolumab

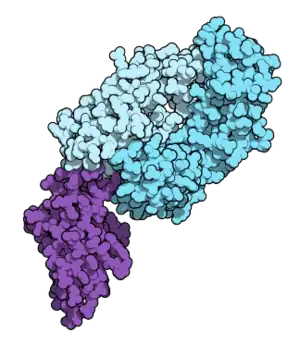

Fab fragment of nivolumab (blue) binding the extracellular domain of PD-1 (purple). From PDB entry 5ggr. | |

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Human |

| Target | PD-1 |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Opdivo |

| Other names | ONO-4538, BMS-936558, MDX1106 |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Immunotherapy[1] |

| Main uses | Cancer[2] |

| Side effects | Tiredness, rash, liver problems, muscles pains, cough[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Intravenous (IV) |

| Defined daily dose | not established[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a614056 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6362H9862N1712O1995S42 |

| Molar mass | 143599.39 g·mol−1 |

Nivolumab, sold under the brand name Opdivo, is a medication used to treat a number of types of cancer.[2] This includes melanoma, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, head and neck cancer, colon cancer, and liver cancer.[2] It is used by slow injection into a vein.[2]

Common side effects include tiredness, rash, liver problems, muscles pains, and cough.[2] Severe side effects may include immune-related lung, intestinal, liver, kidney, skin, or endocrine problems.[2] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby and use when breastfeeding is not recommended.[2][3] Nivolumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that blocks PD-1.[2] It is a type of Immunotherapy and works as a checkpoint inhibitor, blocking a signal that prevents activation of T cells from attacking the cancer.[2][1]

Nivolumab was approved for medical use in the United States in 2014.[2][5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6] In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS about £5266 a month as of 2018.[7] In the United States this amount costs about US$13,556 as of 2019,[8] while in China it is about US$7,000.[9] It is made using Chinese hamster ovary cells.[10]

Medical use

Nivolumab is used as a first line treatment for inoperable or metastatic melanoma in combination with ipilimumab if the cancer does not have a mutation in BRAF,[5] and as a second-line treatment for inoperable or metastatic melanoma following treatment of ipilimumab and, if the cancer has a BRAF mutation, a BRAF inhibitor.[5][11] It is also used to treat metastatic squamous non-small cell lung cancer with progression with or after platinum-based drugs and for treatment of small cell lung cancer[5][12] It also used as a second-line treatment for renal cell carcinoma after anti-angiogenic treatment has failed.[5]

Nivolumab is also used for primary or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, the most common form of bladder cancer. It can be prescribed for locally advanced or metastatic form of the condition that experience disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or have progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.[13]

Nivolumab, and other PD-1 inhibitors, appear to be effective in people with brain metastases[14] and for cancer in people with autoimmune diseases.[15]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established[4]

Side effects

The drug label contains warnings with regard to increased risks of severe immune-mediated inflammation of the lungs, the colon, the liver, the kidneys (with accompanying kidney dysfunction), as well as immune-mediated hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism.[5] Hypothyroidism may affect 8.5% and hyperthyroidism 3.7%.[16] Autoimmune diabetes similar to diabetes mellitus type 1 may occur in approximately 2% of people treated with nivolumab.[16] Colitis may occur due to nivolimumab.

In trials for melanoma, the following side effects occurred in more than 10% of subjects and more frequently than with chemotherapy alone: rash and itchy skin, cough, upper respiratory tract infections, and peripheral edema. Other clinically important side effects with less than 10% frequency were ventricular arrhythmia, inflammation of parts of the eye (iridocyclitis), infusion-related reactions, dizziness, peripheral and sensory neuropathy, peeling skin, erythema multiforme, vitiligo, and psoriasis.[5]

In trials for lung cancer, the following side effects occurred in more than 10% of subjects and more frequently than with chemotherapy alone: fatigue, weakness, edema, fever, chest pain, generalized pain, shortness of breath, cough, muscle and joint pain, decreased appetite, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, constipation, weight loss, rash, and itchy skin.[5]

Levels of electrolytes and blood cells counts were also disrupted.[5]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Use during pregnancy may harm the baby; it is not known if nivolumab is secreted in breast milk but use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[5][3][2]

Pharmacokinetics

Based on data from 909 patients, the terminal half-life of nivolumab is 26.7 days and steady-state concentrations were reached by 12 weeks when administered at 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.[5]: 29 Age, gender, race, baseline LDH, PD-L1 expression, tumor type, tumor size, renal impairment, and mild hepatic impairment do not affect clearance of the drug.[5]: 30

Mechanism of action

T cells protect the body from cancer by killing certain cancer cells. But cancer cells evolve proteins to protect themselves from T cells. Nivolumab blocks those protective proteins. Thus, the T cells can kill the cancer cells.[17][18] This is an example of immune checkpoint blockade.[17][18]

PD-1 is a protein on the surface of activated T cells. If another molecule, called programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 or programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PD-L1 or PD-L2), binds to PD-1, the T cell becomes inactive. This is one way that the body regulates the immune system, to avoid an overreaction.[18] Many cancer cells make PD-L1, which inhibits T cells from attacking the tumor. Nivolumab blocks PD-L1 from binding to PD-1, allowing the T cell to work.[17][18] PD-L1 is expressed on 40–50% of melanomas and has limited expression otherwise in most visceral organs with the exception of respiratory epithelium and placental tissue.[11]

Physical properties

Nivolumab is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin G4 antibody to PD-1.[11] The gamma 1 heavy chain is 91.8% unmodified human design while the kappa light chain is 98.9%.<[19]

History

It was discovered at Medarex, developed by Medarex and Ono Pharmaceutical, and brought to market by Bristol-Myers Squibb (which acquired Medarex in 2009) and Ono.

Nivolumab was invented by Dr. Changyu Wang and his team of scientists at Medarex using Medarex's transgenic mice with a humanized immune system; the discovery and in vitro characterization of the antibody, originally called MDX-1106, was published (much later) in 2014.[20] Medarex licensed Japanese rights to nivolumab to Ono Pharmaceutical in 2005.[21] Bristol-Myers Squibb acquired Medarex in 2009 for $2.4B, largely on the strength of its checkpoint inhibitor program.[22][23]

Promising clinical trial results made public in 2012, caused excitement among industry analysts and in the mainstream media; PD-1 was being avidly pursued as a biological target at that time, with companies including Merck with pembrolizumab (Keytruda), Roche (via its subsidiary Genentech) with atezolizumab, GlaxoSmithKline in collaboration with the Maryland biotech company Amplimmune; and Teva in collaboration with the Israeli biotech company CureTech competing.[24][25]

Ono received approval from Japanese regulatory authorities to use nivolumab to treat unresectable melanoma in July 2014, which was the first regulatory approval of a PD-1 inhibitor anywhere in the world.[21]

Merck received its first FDA approval for its PD-1 inhibitor, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), in September 2014.[26]

Nivolumab received FDA approval for the treatment of melanoma in December 2014.[11][27] In April 2015, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency recommended approval of Nivolumab for metastatic melanoma as a monotherapy.[28]

In March 2015, the U.S. FDA approved it for the treatment of squamous cell lung cancer.[29]

On 19 June 2015, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) granted a marketing authorization valid throughout the European Union.[30]

In November 2015, the FDA approved nivolumab as a second-line treatment for renal cell carcinoma after having granted the application breakthrough therapy designation, fast track designation, and priority review status.[31]

In May 2016, the FDA approved nivolumab for the treatment of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) who have relapsed or progressed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) and post-transplantation brentuximab vedotin.[32]

On 20 December 2017, the FDA granted approval to nivolumab for adjuvant treatment of melanoma with involvement of lymph nodes or for metastatic disease with complete resection.[33]

On 16 April 2018, the FDA granted approval to nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for the first-line treatment of intermediate and poor risk advanced renal cell carcinoma patients.[34]

On 15 June 2018, China's Drug Administration approved nivolumab, the country's first immuno-oncology and the first PD-1 therapy.[35]

Research

Hodgkin's lymphoma

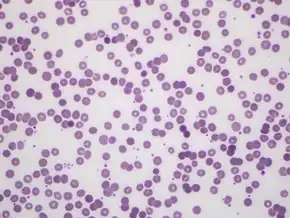

In Hodgkin's lymphoma, Reed-Sternberg cells harbor amplification of chromosome 9p24.1, which encodes PD-L1 and PD-L2 and leads to their constitutive expression. In a small clinical study published in 2015, nivolumab elicited an objective response rate of 87% in a cohort of 20 patients.[24]

Biomarkers

Amplification of chromosome 9p24 may serve as a predictive biomarker in Hodgkin's lymphoma.[24]

Each company pursuing mAbs against PD-1 as drugs developed assays to measure PD-L1 levels as a potential biomarker using their drugs as the analyte-specific reagent in the assay. BMS partnered with Dako on a nivolumab-based assay. However, as of 2015 the complexity of the immune response had hindered efforts to identify people who would be likely to respond well to PD-1 inhibitors;[24] in particular PD-L1 levels appear to be dynamic and modulated by several factors, and efforts to correlate PD-L1 levels before or during treatment with treatment response or duration of response had failed to reveal any useful correlations as of 2015.[11]

Lung cancer

In 2016, BMS announced the results of a clinical trial in which nivolumab failed to achieve its endpoint and was no better than traditional chemotherapy at treating newly diagnosed lung cancer.[36] BMS went on to attempt to win approval for a combination therapy against lung cancer which included nivolumab and BMS's older drug ipilimumab. The application was withdrawn in early 2019 following disappointing clinical trial data.[37]

Infusion times of 60 minutes and 30 minutes appear to have similar pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination) of the treatment.[38]

Melanoma

PD-L1 is expressed in 40-50% of melanomas.[39] Phase I and II clinical trials have shown nivolumab as a promising and durable treatment option in Melanoma as a single agent and in combination with ipilimumab.[11] Phase III trials are ongoing.

References

- 1 2 "Nivolumab (Opdivo) | Cancer information | Cancer Research UK". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Nivolumab Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "Nivolumab (Opdivo) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Opdivo- nivolumab injection". DailyMed. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 852. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ "Opdivo Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ↑ "Bristol-Myers will sell Opdivo in China at half of US cost, setting precedent for checkpoint wave — report". Endpoints News. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ↑ Rajan A, Kim C, Heery CR, Guha U, Gulley JL (September 2016). "Nivolumab, anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody immunotherapy: Role in advanced cancers". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 12 (9): 2219–31. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1175694. PMC 5027703. PMID 27135835.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Johnson DB, Peng C, Sosman JA (March 2015). "Nivolumab in melanoma: latest evidence and clinical potential". Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 7 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1177/1758834014567469. PMC 4346215. PMID 25755682.

- ↑ Sundar R, Cho BC, Brahmer JR, Soo RA (March 2015). "Nivolumab in NSCLC: latest evidence and clinical potential". Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 7 (2): 85–96. doi:10.1177/1758834014567470. PMC 4346216. PMID 25755681.

- ↑ Bushey, R. Gains FDA Approval for Common Bladder Cancer Archived 28 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Drug Discovery & Development, Fri, 02/03/2017.

- ↑ Caponnetto S, Draghi A, Borch TH, Nuti M, Cortesi E, Svane IM, Donia M (May 2018). "Cancer immunotherapy in patients with brain metastases". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 67 (5): 703–711. doi:10.1007/s00262-018-2146-8. hdl:11573/1298742. PMID 29520474.

- ↑ Donia M, Pedersen M, Svane IM (April 2017). "Cancer immunotherapy in patients with preexisting autoimmune disorders". Seminars in Immunopathology. 39 (3): 333–337. doi:10.1007/s00281-016-0595-8. PMID 27730287.

- 1 2 de Filette J, Andreescu CE, Cools F, Bravenboer B, Velkeniers B (March 2019). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Endocrine-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors". Hormone and Metabolic Research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et Metabolisme. 51 (3): 145–156. doi:10.1055/a-0843-3366. PMID 30861560.

- 1 2 3 Pardoll DM (March 2012). "The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 12 (4): 252–64. doi:10.1038/nrc3239. PMC 4856023. PMID 22437870.

- 1 2 3 4 Syn NL, Teng MW, Mok TS, Soo RA (December 2017). "De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting". The Lancet. Oncology. 18 (12): e731–e741. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1. PMID 29208439.

- ↑ WHO Drug Information, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2012. Proposed INN List 107 Archived 3 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Wang C, Thudium KB, Han M, Wang XT, Huang H, Feingersh D, et al. (September 2014). "In vitro characterization of the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab, BMS-936558, and in vivo toxicology in non-human primates". Cancer Immunology Research. 2 (9): 846–56. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0040. PMID 24872026.

- 1 2 John Carroll for FierceBiotech 7 Jul 2014 Anti-PD-1 cancer star nivolumab wins world's first regulatory approval Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Allison M (September 2009). "Bristol-Myers Squibb swallows last of antibody pioneers". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (9): 781–3. doi:10.1038/nbt0909-781. PMID 19741612.

- ↑ John Carroll for FierceBiotech 23 Jul 2009 Bristol-Myers to buy Medarex for $2.1B Archived 4 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 Sharma P, Allison JP (April 2015). "The future of immune checkpoint therapy". Science. 348 (6230): 56–61. Bibcode:2015Sci...348...56S. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8172. PMID 25838373.

- ↑ A Pollack (June 2012). "Drug helps immune system fight cancer". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "FDA approves Keytruda for advanced melanoma" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 September 2014. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "FDA approves Opdivo for advanced melanoma" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ "New treatment for advanced melanoma". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 24 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ "FDA expands approved use of Opdivo to treat lung cancer" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "Opdivo EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ FDA. 23 November 2015 FDA Press Release: FDA approves Opdivo to treat advanced form of kidney cancer Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Nivolumab (Opdivo) for Hodgkin Lymphoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ "FDA grants regular approval to nivolumab for adjuvant treatment of melanoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "FDA approves nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination for intermediate or poor-risk advanced renal cell carcinoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ "Bristol-Myers' Opdivo ushers in a new era as the first I-O therapy approved in China | FiercePharma". www.fiercepharma.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ Loftus, Peter; Rockoff, Jonathan D.; Steele, Anne (5 August 2016). "Bristol Myers: Opdivo Failed to Meet Endpoint in Key Lung-Cancer Study". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ Erman, Michael (24 January 2019). "Bristol-Myers has Opdivo lung cancer setback as sales beat estimates". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Waterhouse D, Horn L, Reynolds C, Spigel D, Chandler J, Mekhail T, Mohamed M, Creelan B, Blankstein KB, Nikolinakos P, McCleod MJ, Li A, Oukessou A, Agrawal S, Aanur N (April 2018). "Safety profile of nivolumab administered as 30-min infusion: analysis of data from CheckMate 153". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 81 (4): 679–686. doi:10.1007/s00280-018-3527-6. PMID 29442139.

- ↑ Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, et al. (August 2002). "Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion". Nature Medicine. 8 (8): 793–800. doi:10.1038/nm730. PMID 12091876.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |