Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

| Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Call-Fleming syndrome, postpartum cerebral angiopathy, benign angiopathy of the central nervous system, migrainous vasospasm, migraine angiitis[1] | |

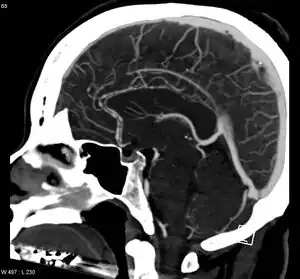

| |

| Significant beading of all intracranial arteries, best demonstrated in the anterior cerebral arties due to RCVS. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Recurrent and severe headaches, vomiting, sensivity to light, confusion, focal neurologic signs, seizures[2][1] |

| Complications | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, stroke[1] |

| Usual onset | 20 to 50 years old[1] |

| Duration | 3 weeks[2] |

| Risk factors | Childbirth, vasoactive drugs, complications of pregnancy[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to an aneurysm, cerebral artery dissection, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, ischemic stroke, pituitary apoplexy, cerebral vasculitis[2][1] |

| Treatment | Calcium channel blockers[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally favorable[1] |

| Frequency | Relatively common[1] |

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is a disease characterized by many areas of constriction and dilation of arteries around the brain.[1] Symptoms typically include recurrent and severe headaches of sudden onset (thunderclap headaches).[1] Other symptoms may include vomiting, sensivity to light, confusion, focal neurologic signs, and seizures.[2][1] Complications may include subarachnoid bleeding and stroke.[1]

Risk factors include childbirth, vasoactive drugs, and complications of pregnancy.[2] Drugs that have been implicated include cocaine, sumatriptan, diet pills, SSRIs, and pseudoephedrine.[2][1] Diagnosis is generally by medical imaging.[1] Other conditions that may present similarly include subarachnoid bleeding due to an aneurysm, cerebral artery dissection, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, ischemic stroke, pituitary apoplexy, and cerebral vasculitis.[2][1]

Calcium channel blockers, such as nimodipine, have been used for treatment.[1] For the vast majority, all symptoms disappear on their own within three weeks.[2] Deficits persist in a minority, with severe complications or death being very rare.[2]

While how often it occurs is unknown, it is believed to be relatively common.[1] Those affected are most often 20 to 50 years old.[1] Females are affected more often than males.[1] The condition was first described in the 1960s; however, the current name did not come into use until 2007.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The key symptom of RCVS is recurrent thunderclap headaches, which occurs in over 95%.[2] In two-thirds of cases, it is the only symptom.[2] These headaches are typically bilateral, very severe and peak in intensity within a minute.[2] They may last from minutes to days, and may be accompanied by nausea, photophobia, phonophobia or vomiting.[2] Some people experience only one headache, but on average there are four attacks over a period of one to four weeks.[2] A milder, residual headache persists between severe attacks for half of people.[2]

About 1–17% of people experience seizures; 8–43% of people show neurologic problems, especially visual disturbances, but also hemiplegia, ataxia, dysarthria, aphasia, and numbness.[2] These neurologic issues typically disappear within minutes or a few hours; more persistent symptoms may indicate a stroke.[2] Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome is present in a small minority of people.[4][5][6]

This condition features the unique property that the person's cerebral arteries can spontaneously constrict and relax back and forth over a period of time without intervention and without clinical findings. Vasospasm is common post subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral aneurysm, but in RCVS only 25% of people have symptoms post subarachnoid hemorrhage.[7]

Causes

The direct cause of the symptoms is believed to be either constriction or dilation of blood vessels in the brain.[2] The pathogenesis is not known definitively, and the condition is likely to result from multiple different disease processes.[3]

Up to two-thirds of RCVS cases are associated with an underlying condition or exposure, particularly vasoactive or recreational drug use, complications of pregnancy (eclampsia and pre-eclampsia), and the adjustment period following childbirth called puerperium.[2] Vasoactive drug use is found in about 50% of cases.[3] Implicated drugs include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, weight-loss pills such as Hydroxycut, alpha-sympathomimetic decongestants, acute migraine medications, pseudoephedrine, epinephrine, cocaine, and cannabis, among many others.[2] It sometimes follows blood transfusions, certain surgical procedures, swimming, bathing, high altitude experiences, sexual activity, exercise, or coughing.[2] Symptoms can take days or a few months to manifest after a trigger.[3]

Following a study and publication in 2007, it is also thought SSRIs, uncontrolled hypertension, endocrine abnormality, and neurosurgical trauma are indicated to potentially cause vasospasm.[8]

Diagnosis

Other conditions with similar symptoms should first be ruled out, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, pituitary apoplexy, cerebral artery dissection, meningitis, and spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak.[2] This may involve a CT scan, lumbar puncture, MRI, and other tests.[2] Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome has a similar presentation, and is found in 10–38% of people.[2]

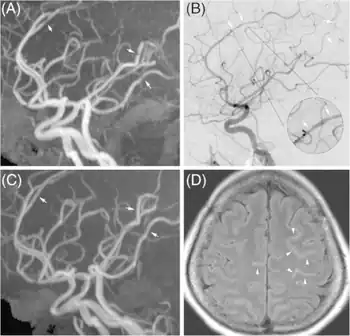

RCVS is diagnosed by detecting diffuse reversible cerebral vasoconstriction.[2] Catheter angiography is ideal, but computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance angiography can identify about 70% of cases.[2] Multiple angiographies may be necessary.[2] Because other diseases (such as atherosclerosis) have similar angiographic presentations, it can only be conclusively diagnosed if vasoconstriction resolves within 12 weeks.[2]

Treatment

As of 2014, no treatment strategy has yet been investigated in a randomized clinical trial.[2] Verapamil, nimodipine, and other calcium channel blockers may help reduce the intensity and frequency of the headaches.[2] A clinician may recommend rest and the avoidance of activities or vasoactive drugs which trigger symptoms (see § Causes).[2] Analgesics and anticonvulsants can help manage pain and seizures, respectively.[2]

Prognosis

All symptoms normally resolve within three weeks, and may only last days.[2] Permanent deficits are seen in a minority of people, ranging from under 10% to 20% in various studies.[2] Less than 5% of people experience progressive vasoconstriction, which can lead to stroke, progressive cerebral edema, or even death.[2] Severe complications appear to be more common in postpartum mothers.[3]

Epidemiology

The incidence of RCVS is unknown, but it is believed to be "not uncommon", and likely under-diagnosed.[2][3] One small, possibly biased study found that the condition was eventually diagnosed in 45% of outpatients with sudden headache, and 46% of outpatients with thunderclap headache.[2]

The average age of onset is 42, but RCVS has been observed in those aged from 19 months to 70 years.[2] Children are rarely affected.[2] It is more common in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.4:1.[3]

History

Case studies of the condition first appeared in the 1960s, but it was not then recognized as a distinct entity.[3] In 1983, French researchers published a case series of 11 people, terming the condition acute benign cerebral angiopathy.[2] Gregory Call and Marie Fleming were the first two authors of a report in which doctors from Massachusetts General Hospital, led by C. Miller Fisher, described 4 people, alongside 12 previous case studies, with the characteristic symptoms and abnormal cerebral angiogram findings.[3][9] The name Call-Fleming syndrome refers to these researchers.[2]

A 2007 review by Leonard Calabrese and colleagues proposed the name reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, which has since gained widespread acceptance.[2][10] This name merges various conditions that were previously treated as distinct entities, including Call-Fleming syndrome, postpartum angiopathy, and drug-induced angiopathy.[3] Other names may still be used for particular forms of the condition.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Nesheiwat, O; Al-Khoury, L (January 2021). "Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndromes". PMID 31869187.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Mehdi, A. & Hajj-Ali, R. A. (2014). "Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a comprehensive update". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 18 (9): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s11916-014-0443-2. PMID 25138149. S2CID 7457809.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Miller, T. R.; Shivashankar, R.; Mossa-Basha, M. & Gandhi, D. (2015). "Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical course" (PDF). American Journal of Neuroradiology. 36 (8): 1392–1399. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A4214. PMID 25593203. S2CID 12431927. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-15. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ↑ Chen, Shih-Pin; Fuh, Jong-Ling; Wang, Shuu-Jiun (2010). "Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: an under-recognized clinical emergency". Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 3 (3): 161–171. doi:10.1177/1756285610361795. PMC 3002654. PMID 21179608.

- ↑ Miller TR, Shivashankar R, Mossa-Basha M, and Gandhi D (2015). "Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome, Part 1 Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Course" (PDF). American Journal of Neuroradiology. 36 (8): 1392–9. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A4214. PMID 25593203. S2CID 12431927. Archived from the original on 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Ducros A (2012). "Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome" (PDF). The Lancet Neurology. 11 (10): 906–17. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70135-7. PMID 22995694. S2CID 13616987. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ↑ Moustafa RR, Allen CM, Baron JC (2008). "Call-Fleming syndrome associated with subarachnoid haemorrhage: three new cases". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 79 (5): 602–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.134635. PMC 3029638. PMID 18077478. S2CID 36857208.

- ↑ Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB (January 2007). "Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (1): 34–44. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007. PMID 17200220. S2CID 8628852.

- ↑ Call GK, Fleming MC, Sealfon S, Levine H, Kistler JP, Fisher CM (1988). "Reversible cerebral segmental vasoconstriction". Stroke. 19 (9): 1159–70. doi:10.1161/01.str.19.9.1159. PMID 3046073.

- ↑ Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB (2007). "Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes". Annals of Internal Medicine. 146 (1): 34–44. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007. PMID 17200220. S2CID 8628852.

External links

| Classification |

|---|