Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| GFAP stained microscopic section of a subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | |

Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA, SGCA, or SGCT) is a low-grade astrocytic brain tumor (astrocytoma) that arises within the ventricles of the brain.[1] It is most commonly associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Although it is a low-grade tumor, its location can potentially obstruct the ventricles and lead to hydrocephalus.

Signs and symptoms

Individuals with this type of tumor may have no symptoms if cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow remains open. Obstruction of CSF flow will result in the symptoms associated with increased CSF pressure: nausea, vomiting, headache (often positional), lethargy, blurry or double vision, new or worsened seizures, and personality change.[2]

Diagnosis

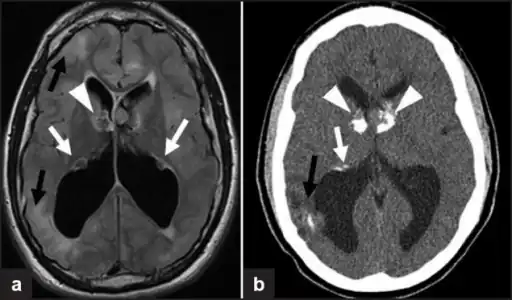

a,b)Images of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas arrowheads

a,b)Images of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas arrowheads MRI of brain with sub-ependymal giant cell astrocytoma

MRI of brain with sub-ependymal giant cell astrocytoma

Diagnosis is made by imaging with a contrast-enhanced MRI or CT scan of the brain.[3]

Screening

It is recommended that children with TSC be screened for SEGA with neuroimaging every 1–3 years.[1]

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

Two related drugs have been shown to shrink or stabilize subependymal giant cell tumors: rapamycin and everolimus. These both belong to the mTOR inhibitor class of immunosuppressants, and are both contraindicated in patients with severe infections.

Rapamycin showed efficacy in five cases of SEGA in TSC patients, shrinking their tumor volumes by an average of 65%. However, after the drug was stopped, the tumors regrew.

Everolimus, which has a similar structure as rapamycin, but with slightly increased bioavailability and shorter half-life, was studied in 28 patients with SEGA. There was a significant reduction in SEGA size in 75% of the patients, and a mild improvement in their seizures. Everolimus was approved for the treatment of SEGA by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October, 2010.[1]

Surgery

A NIH Consensus Conference report in 1999 recommends that any SEGA that is growing or causing symptoms should be surgically removed.[2] Tumors are also removed in cases where a patient is suffering from a high seizure burden.[1] If a tumor is rapidly growing or causing symptoms of hydrocephalus, deferring surgery may lead to vision loss, need for ventricular shunt, and ultimately death. Total removal of the tumor is curative.

Surgery to remove intraventricular tumors also carries risks of complications or death. Potential complications include transient memory impairment, hemiparesis, infection, chronic ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, stroke, and death.[1]

Prognosis

After complete surgical removal, a SEGA tumor does not grow back. They do not metastasize to other parts of the body. However, the patient is still at risk for, and often develops, new tumors arising from subependymal nodules elsewhere in the ventricular system.

Epidemiology

SEGAs arise in 5-20% of TSC patients.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campen CJ, Porter BE (August 2011). "Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma (SEGA) Treatment Update". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 13 (4): 380–385. doi:10.1007/s11940-011-0123-z. PMC 3130084. PMID 21465222.

- 1 2 "Supependymal Giant Cell Tumor (SGCT) or Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma (SEGA)" (PDF). Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance. June 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ↑ Roth, Jonathan; Roach, E. Steve; Bartels, Ute; Jóźwiak, Sergiusz; Koenig, Mary Kay; Weiner, Howard L.; Franz, David N.; Wang, Henry Z. (December 2013). "Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: diagnosis, screening, and treatment. Recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference 2012". Pediatric Neurology. 49 (6): 439–444. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.017. ISSN 1873-5150. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

External links

| Classification |

|---|