Doxylamine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Unisom, Vicks Formula 44 (in combination with Dextromethorphan), others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | First-generation antihistamine[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Doxylamine |

| MedlinePlus | a682537 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | By mouth: 24.7%[2] Intranasal: 70.8%[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2C9)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 10–12 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Urine (60%), feces (40%)[4] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

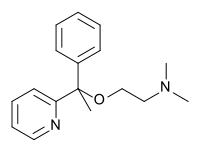

| Formula | C17H22N2O |

| Molar mass | 270.369 g·mol−1 |

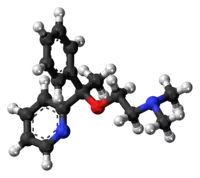

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Doxylamine is a first-generation antihistamine used for trouble sleeping and allergies.[1] Use for trouble sleeping should be short term.[1] Onset of effects is about half an hour.[1] It is also used in combination with vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.[5] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include sleepiness.[1] Other side effects include dry mouth, urinary retention, and glaucoma.[1] Children may get restless.[1] Use in pregnancy appears safe.[6] It works by blocking H1 receptors and thus blocking the effects of histamine.[1]

Doxylamine was first described in 1948.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the United States it costs less than 10 USD for 30 tablets of 25 mg as of 2020.[8]

Medical uses

Allergies

Doxylamine is an antihistamine used to treat sneezing, runny nose, watery eyes, hives, skin rash, itching, and other cold or allergy symptoms.

Trouble sleeping

It is also used as a short-term treatment for sleep problems (insomnia).[9] As of 2004, doxylamine and diphenhydramine were the agents most commonly used to treat short-term insomnia.[10] As of 2008, antihistamines were not recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for treatment of long term insomnia "due to the relative lack of efficacy and safety data".[11]

Morning sickness

It is used in the combination drug pyridoxine/doxylamine to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.[12][13]

Dosage

The typical dose is 25 mg before bed to help with sleep.[1] For allergies 12.5 mg up to 6 times per day may be used.[1]

Side effects

Doxylamine succinate is a potent anticholinergic and has a side-effect profile common to such drugs, including dry mouth, ataxia, urinary retention, drowsiness, memory problems, inability to concentrate, hallucinations, psychosis, and a marked increased sensitivity to external stimuli. Like many hypnotics, it should not be combined with other antihistamines, such as cetirizine (Zyrtec) or diphenhydramine (Benadryl), as this combination can increase the risk of serious side effects. Some people can have a different reaction: instead of sedating, it stimulates. Using doxylamine over a long period of time is not recommended. However, the drug is not addictive. It can be mildly psychologically addictive to some people. If used for longer periods of time, withdrawal effects are unlikely to be experienced with prolonged use, but mild withdrawal symptoms are likely if taken long-term.

Because of its relatively long elimination half-life (10–12 hours), doxylamine is associated with daytime/next-day drowsiness, grogginess, dry mouth, and tiredness when used as a hypnotic.[14] The shorter elimination half-life of diphenhydramine (4–8 hours) may give it an advantage over doxylamine in this regard.[15]

Unlike with diphenhydramine, case reports of coma and rhabdomyolysis have been reported with doxylamine.[3]

Toxicity

Doxylamine succinate is generally safe for administration to healthy adults. The median lethal dose (LD50) is estimated to be 50–500 mg/kg in humans.[16] Symptoms of overdose may include dry mouth, dilated pupils, insomnia, night terrors, euphoria, hallucinations, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, and death.[17] Fatalities have been reported from doxylamine overdose. These have been characterized by coma, tonic-clonic (or grand mal) seizures and cardiorespiratory arrest. Children appear to be at a high risk for cardiorespiratory arrest. A toxic dose for children of more than 1.8 mg/kg has been reported. A 3-year-old child died 18 hours after ingesting 1000 mg doxylamine succinate.[4] Rarely, an overdose results in rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury.[18]

Studies of doxylamine's carcinogenicity in mice and rats have produced positive results for both liver and thyroid cancer, especially in the mouse.[19] The carcinogenicity of the drug in humans is not well studied, and the IARC lists the drug as "not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans".[20]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| NET | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| DAT | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| 5-HT2A | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| 5-HT2C | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| α1B | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| α2A | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| α2B | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| α2C | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| H1 | 42 | Human | [22] |

| H2 | ND | ND | ND |

| H3 | >10,000 | Human | [22] |

| H4 | ND | ND | ND |

| M1 | 490 | Human | [22] |

| M2 | 2,100 | Human | [22] |

| M3 | 650 | Human | [22] |

| M4 | 380 | Human | [22] |

| M5 | 180 | Human | [22] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Doxylamine acts primarily as an antagonist or inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.[23][22] This action is responsible for its antihistamine and sedative properties.[23][22] To a lesser extent, doxylamine acts as an antagonist of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors,[23][22] an action responsible for its minor hypnotic, anticholinergic, and (at high doses) deliriant effects.[23][22]

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of doxylamine is 24.7% for oral administration and 70.8% for intranasal administration.[2] The Tmax of doxylamine is 1.5 to 2.5 hours.[3] Its elimination half-life is 10 to 12 hours.[3] Doxylamine is metabolized in the liver primarily by the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP2C9.[3] The main metabolites are N-desmethyldoxylamine, N,N-didesmethyldoxylamine, and doxylamine N-oxide.[24] Doxylamine is eliminated 60% in the urine and 40% in feces.[4]

History

Doxylamine is a first-generation antihistamine sleep aid with weak hypnotic and calming effects first reported in 1949.[25]

Society and culture

Formulations

Doxylamine is primarily used as the succinic acid salt, doxylamine succinate.

- It is the sedating ingredient of NyQuil (generally in combination with dextromethorphan and acetaminophen).

- In Commonwealth countries, such as Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, doxylamine is available prepared with paracetamol (acetaminophen) and codeine under the brand name Dolased, Propain Plus, Syndol, or Mersyndol, as treatment for tension headache and other types of pain.

- Doxylamine succinate is used in general over-the-counter sleep-aids branded as Somnil (South Africa), Dozile, Donormyl, Lidène (France, Russian Federation), Dormidina (Spain, Portugal), Restavit, Unisom-2, Sominar (Thailand), and Sleep Aid (generic, Australia).

- In the United States:

- doxylamine succinate is the active ingredient in many over-the-counter sleep-aids branded under various names.

- doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) are the ingredients of Diclegis, approved by the FDA in April 2013 becoming the only drug approved for morning sickness[26] with a class A safety rating for pregnancy (no evidence of risk).

- In Canada:

- doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine (vitamin B6) are the ingredients of Diclectin, which is used to prevent morning sickness.

- It is also available in combination with vitamin B6 and folic acid under the brand name Evanorm (marketed by Ion Healthcare)..

- In India

- Doxylamine preparations are available typically in combination with Pyridoxine that may also contain folic acid. Doxylamine usage is thus restricted for pregnant women.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Doxylamine Succinate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 Pelser A, Müller DG, du Plessis J, du Preez JL, Goosen C (2002). "Comparative pharmacokinetics of single doses of doxylamine succinate following intranasal, oral and intravenous administration in rats". Biopharm Drug Dispos. 23 (6): 239–44. doi:10.1002/bdd.314. PMID 12214324. S2CID 32126626.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Meir H. Kryger; Thomas Roth; William C. Dement (1 November 2010). Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 925–. ISBN 978-1-4377-2773-9. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 "New Zealand Datasheet: Doxylamine Succinate" (PDF). Medsafe, New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. 16 July 2008. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ↑ BNF 79 : March 2020. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. p. 442. ISBN 9780857113658.

- ↑ Briggs, Gerald G.; Freeman, Roger K.; Yaffe, Sumner J. (2008). Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. Obstetric Medicine. Vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 89. doi:10.1258/om.2009.090002. ISBN 978-0-7817-7876-3. PMC 4989726.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 546. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ "Compare Doxylamine Prices". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Ringdahl, EN; Pereira, SL; Delzell JE, Jr (2004). "Treatment of primary insomnia". The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 17 (3): 212–9. doi:10.3122/jabfm.17.3.212. PMID 15226287.

- ↑ Schutte-Rodin, S; Broch, L; Buysse, D; Dorsey, C; Sateia, M (15 October 2008). "Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 4 (5): 487–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27286. PMC 2576317. PMID 18853708. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ↑ Madjunkova, S; Maltepe, C; Koren, G (June 2014). "The delayed-release combination of doxylamine and pyridoxine (Diclegis®/Diclectin®) for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy". Paediatric Drugs. 16 (3): 199–211. doi:10.1007/s40272-014-0065-5. PMC 4030125. PMID 24574047.

- ↑ Cada, DJ; Demaris, K; Levien, TL; Baker, DE (October 2013). "Doxylamine succinate/pyridoxine hydrochloride". Hospital Pharmacy. 48 (9): 762–6. doi:10.1310/hpj4809-762. PMC 3857125. PMID 24421551.

- ↑ Alon Y. Avidan (29 June 2017). Review of Sleep Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 394–. ISBN 978-0-323-47349-1. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Paul Professor Rutter; David Newby (11 September 2015). Community Pharmacy ANZ – eBook: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-7295-8345-9. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ DOXYLAMINE SUCCINATE Archived 9 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. hazard.com.

- ↑ Syed, Husnain; Sumit Som; Nazia Khan; Wael Faltas (17 March 2009). "Doxylamine toxicity: seizure, rhabdomyolysis and false positive urine drug screen for methadone". BMJ Case Reports. 2009 (90): 845. doi:10.1136/bcr.09.2008.0879. PMC 3028279. PMID 21686586.

- ↑ Leybishkis, B.; Fasseas, P.; Ryan, K. F. (2001). "Doxylamine overdose as a potential cause of rhabdomyolysis". American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 322 (1): 48–9. doi:10.1097/00000441-200107000-00009. PMID 11465247.

- ↑ Doxylamine succinate (CAS 562-10-7) Archived 1 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. berkeley.edu.

- ↑ DOXYLAMINE SUCCINATE Archived 4 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – Summaries & Evaluations.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Krystal AD, Richelson E, Roth T (2013). "Review of the histamine system and the clinical effects of H1 antagonists: basis for a new model for understanding the effects of insomnia medications". Sleep Med Rev. 17 (4): 263–72. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.001. PMID 23357028.

- 1 2 3 4 Vande Griend JP, Anderson SL (2012). "Histamine-1 receptor antagonism for treatment of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 52 (6): e210–9. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2012.12051. PMID 23229983.

- ↑ Holder, C. L.; Korfmacher, W. A.; Slikker Jr, W.; Thompson Jr, H. C.; Gosnell, A. B. (1985). "Mass spectral characterization of doxylamine and its rhesus monkey urinary metabolites". Biomedical Mass Spectrometry. 12 (4): 151–158. doi:10.1002/bms.1200120403. PMID 2861861. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ Sperber, Nathan.; Papa, Domenick.; Schwenk, Erwin.; Sherlock, Margaret. (1949). "Pyridyl-Substituted Alkamine Ethers as Antihistaminic Agents". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (3): 887–890. doi:10.1021/ja01171a034. PMID 18113525.

- ↑ Slaughter, Shelley R.; Hearns-Stokes, Rhonda; van der Vlugt, Theresa; Joffe, Hylton V. (2014). "FDA Approval of Doxylamine–Pyridoxine Therapy for Use in Pregnancy". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1081–1083. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1316042. PMID 24645939.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|