This article was co-authored by Tasha Rube, LMSW and by wikiHow staff writer, Janice Tieperman. Tasha Rube is a Licensed Social Worker based in Kansas City, Kansas. Tasha is affiliated with the Dwight D. Eisenhower VA Medical Center in Leavenworth, Kansas. She received her Masters of Social Work (MSW) from the University of Missouri in 2014.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article has 15 testimonials from our readers, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 1,004,238 times.

It can be a devastating and helpless experience to watch a friend, loved one, or acquaintance go through a mental health crisis or serious substance abuse struggle. You aren’t completely out of options, though—if you’re worried about this person’s health and safety, you can potentially get them legally admitted to a mental hospital (also known as involuntary commitment). We’ll walk you through all the ins and outs of the process so the struggling individual in your life can start their journey of healing and recovery. We’ll even touch on how to voluntarily commit yourself to a mental hospital, so you can get the care and support you need during a challenging time.

Note: Always call emergency services (911 in the U.S.) if you or someone else are in serious danger. If a friend or loved one is actively suicidal, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988.

Things You Should Know

- Call emergency services if someone is a danger to themselves or others, or file a petition in your state to get the involuntary commitment process started.

- Individuals can get involuntarily committed if a mental health professional and judge/magistrate feel that it’s best for them.

- The involuntary commitment process involves 3 major steps: an emergency psychiatric evaluation, inpatient treatment, and assisted outpatient treatment.

- Commit yourself to a hospital voluntarily if you need extra care and support to manage your mental illness.

Steps

Involuntary Commitment Process

-

1The individual is taken into emergency custody and evaluated. In some states, relatives and spouses can request an emergency hold for an individual; in other places, only psychiatrists, doctors, and law enforcement officers can make the request. Depending on the state, the individual is held temporarily (usually at least 48 hours).[8]

- Many states allow emergency holds to last at least 72 hours, while a small handful of states allow for shorter detainment periods.

-

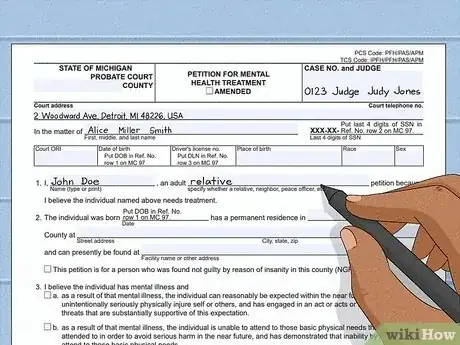

2A petition is filed for the individual to receive inpatient treatment. Some states allow family members to file this petition, while other places only let mental health professionals get the process started. During this time, a court will decide if the individual meets the state’s criteria for involuntary commitment (like being gravely disabled or a danger to themselves or others).[9]

- In some cases, the court might recommend supervised outpatient treatment for a person rather than inpatient care. This is known as “step-up AOT.”

- You might be asked to testify in this court hearing if you’ve personally observed the person’s dangerous behavior.[10]

-

3The individual stays at an inpatient facility for a set amount of time. The length of inpatient treatment varies from state to state. Washington and California, for instance, only mandate 2 weeks of inpatient hospitalization, while Massachusetts, Rhode Island, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Georgia, and Florida all mandate 6 months of hospitalization. Click here to get a closer look at your state’s procedures.

- The court typically gets to choose which facility the person goes to.[11]

-

4Hospitalization can be extended if a mental health professional recommends it.[12] Most states require a court order for this process to go forward, while a few states (like Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennessee, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) do not. The length of this extended inpatient treatment also depends on the state—some places, like Delaware and Arizona, cap the extra treatment at 90 days, while other places, like Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nebraska, Mississippi, Indiana, Ohio, South Carolina, New Jersey, and Connecticut, don’t have a maximum time limit.[13]

-

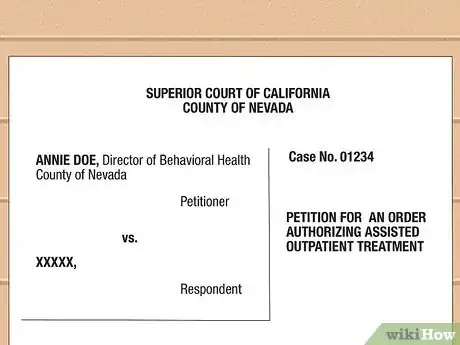

5A petition gets filed for the individual to receive AOT. After receiving inpatient treatment for a set amount of time, a judge decides if the individual can transition to court-monitored outpatient treatment—this is also known as “step-down AOT.”[14]

- When the court allows it, the individual can later switch to a voluntary, community-based treatment plan.

How to Voluntarily Commit Yourself

-

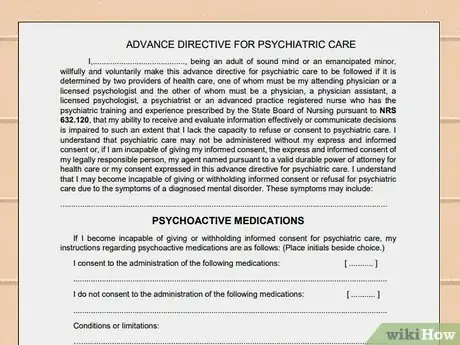

1Fill out a Psychiatric Advance Directive (PAD) beforehand. List the types of medications you would (and wouldn’t!) like to take during your treatment, if you’d want future visitors, and who you want caring for your home, bills, and other obligations while you’re hospitalized. You can even include the name of someone who can make decisions on your behalf (an “agent”) if you’re ever not in the right frame of mind to make decisions for yourself. Bring this form with you whenever you want to be hospitalized.[15]

- You don’t have to fill this out, but it can be a big help if you’re considering inpatient mental health treatment in the future.

- Click here for a master list of PAD forms and PAD FAQs organized by state.

-

2Choose the hospital or treatment facility you’d like to stay at. Do you need round-the-clock, in-depth care for your mental illness, or are you looking for partial care? Search for hospitals and facilities in your area that really cater to your treatment needs.[16]

- Psychiatric wings in hospitals: 24/7 in-patient care with psychiatrists and therapists

- Public psychiatric hospital: A separate hospital that offers both short- and long-term care for people with financial difficulties

- Partial hospitalization: An option that’s less intense than 24/7 treatment programs

- Residential care: 24/7 care offered in a residential, non-hospital setting

- Click here to find mental illness treatment centers in your area, and here to find substance abuse treatment centers.

-

3Check in to the facility and get a physical exam. Chat with staff members so you have a good idea of how the treatment center works and what you can expect there. Before you’re onboarded, a doctor will give you a medical check-up so they can take a closer look at your physical health. Before you officially check yourself in, feel free to ask questions like:[17]

- Who will be treating me at the hospital? How often will I meet with them?

- Who can visit me when I’m at the hospital, and how long can they visit me for?

- What is the rooming situation like at your facility?

- What is a typical daily schedule at your facility?

-

4Check with your facility to see when you can leave. At some hospitals, you can check yourself out whenever you feel comfortable and ready to do so. In some cases, you might need the okay from the hospital—check with the facility and see what their policy is.[18]

Warnings

- Involuntarily committing someone doesn’t always guarantee that they’ll receive treatment. Many states give patients the right to turn down treatment.[22]⧼thumbs_response⧽

- If you’re really worried about your personal health and safety, it could be worth filing a restraining order against the person in question.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://mentalillnesspolicy.org/national-studies/state-standards-involuntary-treatment.html

- ↑ https://mentalillnesspolicy.org/national-studies/state-standards-involuntary-treatment.html

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://drugfree.org/drug-and-alcohol-news/many-states-allow-involuntary-commitment-addiction-treatment/

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://dmh.mo.gov/behavioral-health/help/civil

- ↑ https://www.mass.gov/service-details/section-35-the-process

- ↑ https://eriecountypa.gov/departments/human-services/mental-health/voluntary-and-involuntary-commitment/

- ↑ https://lawatlas.org/datasets/long-term-involuntary-commitment-laws

- ↑ https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/grading-the-states.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mhanational.org/psychiatric-advance-directives-taking-charge-your-care

- ↑ https://www.mhanational.org/hospitalization

- ↑ https://www.mhanational.org/hospitalization

- ↑ https://www.mhanational.org/hospitalization

- ↑ https://screening.mhanational.org/content/do-i-need-go-hospital/?layout=actions_c

- ↑ https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mental-illness/in-depth/intervention/art-20047451

- ↑ https://www.mass.gov/service-details/section-35-the-process

- ↑ https://lawatlas.org/datasets/long-term-involuntary-commitment-laws

-Step-14-Version-2.webp)

-Step-14-Version-2.webp)

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...