This article was co-authored by Sam Lagor, MSc. Sam Lagor is a Geologist with over eight years of experience. He specializes in engineering geology (dams, bridges, and tunnels) and mineral exploration (gold, lead/zinc, andindustrial minerals). Sam holds a BS in Geology from St. Lawrence University and an MS in Geology from The University of Vermont. He is also a member of the Geological Society of America and the American Institute of Professional Geologists.

There are 18 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 33,204 times.

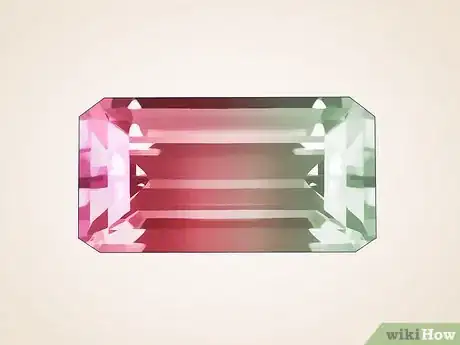

Tourmaline is a type of mineral (a crystalline boron silicate, to be exact) formed by intense hydrothermal activity. Because it can be composed of so many different elements, tourmaline occurs in a wider variety of colors and color combinations than any other natural mineral on the planet. This same visual diversity that makes tourmaline so beautiful can also make it hard to confidently identify. Fortunately, taking a close look at a few basic features can often be enough to make you reasonably sure.

Steps

Examining Your Specimen

-

1Check to see whether your mineral has prismatic crystals. Gems with prismatic crystals have a number of flat, elongated, clearly defined faces, oftentimes with one or more parallel sets. Tourmaline in particular usually has rounded edges, which means that the lines separating each face will be smooth and faint rather than sharp and angular.[1]

- You’ll be able to tell right away whether your specimen is prismatic as opposed to, say, banded, fibrous, geodic, or stalactitic.[2]

-

2Look for a triangular or hexagonal shape. Hold the mineral in one hand and eyeball one of the crystal offshoots from a top-down perspective. Most tourmaline crystals have either a triangular or hexagonal cross section. If the stone you’re investigating has any other shape, chances are good that it’s something else.[3]

- A typical tourmaline gem will look something like a pencil, with a long, narrow, 6-sided shaft. They may even taper to a slight point on one end. Just don’t bother searching for an eraser!

Advertisement -

3Check for thin grooved lines along the surface of the crystals. These lines are known as "striations," and they appear on many different kinds of minerals. Striations are similar to the grain in wood. With tourmaline, they'll run lengthwise along the shaft of each crystal.[4]

- Striations are created by the intense conditions of geological processes like hydrothermal activity, which is the most common source of tourmaline.

Tip: Mineral striations are almost always visible to the naked eye, so you shouldn’t need a magnifying glass or hand lens in order to see them. However, one of these tools may come in handy if the specimen you’re inspecting is especially small or light in color.[5]

-

4Pay attention to the way the colors are arranged in multicolored minerals. In most cases, the colors in tourmaline are confined to small sections or “zones,” which can be arranged throughout its cross section or along the length of its crystals. For example, a piece of genuine tourmaline may have a pale pink section, a vivid green section, and a lustrous yellow section all in a single neat row.[6]

- Tourmaline’s many colors remain separated, for the most part, and rarely mingle the way they do in iridescent minerals like ammolite, opal, or pyrite.

-

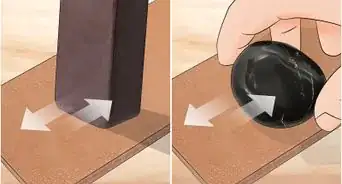

5Perform a simple scratch test to see how hard your stone is. Grab a knife with a steel blade and rub the edge back and forth along the surface of the stone a few times. If it leaves a mark, then what you’re holding probably isn’t tourmaline. If the stone scratches or dulls the knife, however, it may just be the real deal.[7]

- Tourmaline is an extremely hard mineral that rates between 7 and 7.5 on the Mohs Hardness Scale, a testing system used to measure the hardness of minerals. By comparison, steel-bladed knives only have a hardness rating of around 5-6.[8]

- It’s important to use a knife made from solid steel. If the blade is molded from a weaker type of metal, it could be susceptible to scratching even by minerals with a lower hardness rating.

-

6Take your specimen to a gemologist to obtain an exact profile. To find a gemologist in your area, run a quick search for “gemologist” plus the name of your town or city. A skilled gemologist will have the knowledge and resources needed to carry out specialized identifying procedures, such as determining the stone’s refractive index and testing for qualities like birefringence.[9]

- There’s a relatively small number of reputable gemstone testing laboratories in the United States, so it may be necessary to send in your specimen for examination.

- Most jewelry stores also keep at least one gemstone appraiser on staff. One of these professionals may be willing to take a look at your mystery stone for a price.[10]

- Retaining the services of an expert is the only surefire way to find out what a particular mineral is. You can only gather so much on your own.

Differentiating Common Types of Tourmaline

-

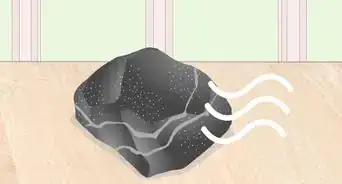

1Assume that your specimen is schorl if it’s smooth and black. Schorl is by far the most common species of tourmaline. Like other varieties, it is a byproduct of hydrothermal activity, and often appears as an accessory mineral to igneous and metamorphic rocks. Schorl is noteworthy for its short, rounded, stubby crystals and opaque, all-black color.[11]

- Since it’s so abundant, schorl isn’t considered particularly valuable, and is not ordinarily cut as a gem or used for jewelry.[12]

-

2Classify brown varieties of tourmaline as dravite. Dravite is another fairly common form of tourmaline. It comes almost exclusively in shades of brown, with dark yellow, burnt orange, brownish-black, and army green derivations. Because of this, it is sometimes known colloquially as “brown tourmaline.”[13]

- Most varieties of dravite will shine with a golden yellow aura when exposed to bright UV light.

-

3Use a keen eye to distinguish between uvite and dravite. Uvite is a close cousin of dravite. In fact, they’re frequently mistaken for one another. While uvite isn’t generally as colorful as other, more popular kinds of tourmaline, it has been unearthed in pleasant lavender, blue-green, and copper hues.[14]

- To make things even more complicated, uvite and dravite have been known to develop as separate parts of the same crystal.

- If your specimen has any amount of green, blue, or purple to it, it’s more likely to be uvite than dravite.

-

4Look for one or more vibrant colors that might indicate elbaite. Elbaite is a somewhat rare and prized form of tourmaline that is mined from deposits of granite pegmatite. It occurs in almost every color imaginable, from muted pinks and reds to vivid blues and greens. Two or more of these colors are frequently displayed within the same crystal.[15]

- Though not seen as frequently, there are also black, white, brown, yellow, orange, purple, and colorless varieties of elbaite.

- Subcategories of elbaite receive their names based on their color—verdelite, for example, are green, while indicolite are blue and rubellite are red.[16]

- When most gem enthusiasts think of tourmaline, they picture elbaite.

Tip: Elbaite tourmaline is valued quite highly by collectors. If you have some in your possession, you may be able to get a decent chunk of change for it.[17]

-

5Be on the lookout for the brilliant blues and greens of paraiba. Paraiba is a relatively new addition to the tourmaline family that was only discovered as recently as the late 1980s. Thank to its dazzling coloration and extreme rarity, it didn't take long for it to become one of the most valuable and sought-after gems in the entire world.

- Paraiba is instantly recognizable by its small size, smooth, rounded shape, and stunning visual quality, which is characterized by an electric aquamarine glow.[18]

- It's unlikely that you have a piece of paraiba tourmaline on your hands, but if you do, consider yourself lucky. It's not unusual for the mineral to sell for as much as $10,000 per carat at auction![19]

Warnings

- Tourmaline occurs in a nearly endless variety of colors, so the color of your specimen alone won’t be much help when it comes to making a positive ID.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://geology.com/minerals/tourmaline.shtml

- ↑ http://www.geologyin.com/2019/10/crystal-habits-and-forms.html

- ↑ https://geology.com/minerals/tourmaline.shtml

- ↑ https://www.minerals.net/mineral/tourmaline.aspx

- ↑ https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-geology/chapter/outcome-identifying-minerals/

- ↑ https://geology.com/minerals/tourmaline.shtml#properties

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/tell-synthetic-pink-tourmaline-8610223.html

- ↑ https://geology.com/minerals/mohs-hardness-scale.shtml

- ↑ https://www.lotusgemology.com/index.php/library/articles/452-gem-testing-labs-tips-on-choosing-a-gem-testing-lab-lotus-gemology

- ↑ https://www.angieslist.com/articles/5-questions-ask-hiring-appraiser.htm

- ↑ https://www.minerals.net/mineral/schorl.aspx

- ↑ https://geology.com/minerals/tourmaline.shtml

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XuDD2X4EpmE&feature=youtu.be&t=10

- ↑ https://www.minerals.net/mineral/uvite.aspx

- ↑ https://www.mindat.org/min-1364.html

- ↑ https://www.gia.edu/gia-gem-project-tourmaline

- ↑ https://www.mindat.org/article.php/836/Advice+for+people+selling+and+sorting+a+mineral+collection.

- ↑ https://www.gemstone.org/education/gem-by-gem/227-paraiba-tourmaline

- ↑ https://www.gia.edu/tourmaline-quality-factor

- ↑ https://www.jewelrynotes.com/finding-tourmaline/