This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD. Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 33,435 times.

Do your teachers always mark up your essays with red ink? Are you eager to learn how to express yourself clearly and effectively? If so, there are plenty of steps you can take to improve your essay writing skills. Improve your grammar, refine your style, and learn how to structure a well-organized essay. Since academic essays are especially tricky, learn the ins and outs of formal, scholarly writing. Be sure to read as much as possible; seeing how other authors use language can improve your own writing.

Steps

Improving Your Grammar and Style

-

1Review basic grammar rules. If you have trouble with grammar, familiarize yourself with topics such as subject-verb agreement, verb tenses, proper word order (called syntax), and punctuation. When you’re actually writing an essay, run a quick online search if you think a particular sentence might be grammatically incorrect.

- For example, while writing, you might not know whether to use “who” or “whom,” so you check the rule online. You’d use “who” for a person doing an action (called a subject), and “whom” for someone who gets something done to them (called an object). “Who called you,” and “Whom did you call” are grammatically correct.

- Find a general guide on grammar at https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/grammar/index.html.

- If you’re a student, see if your school has a writing lab. If so, they’ll have useful resources on grammar and tutors who can help you improve basic writing skills.[1]

-

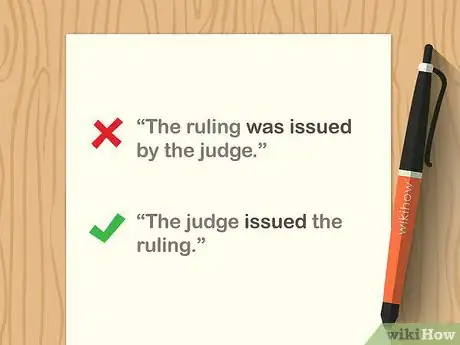

2Write in the active voice whenever possible. Active voice is stronger and usually more concise than the passive voice. For instance, write “The judge issued the ruling,” instead of, “The ruling was issued by the judge.” The second example is wordy and lacks energy, while the first is sharp and clear.”[2]

- That said, some exceptions apply. If you’re discussing a scientific study, “The subjects were divided into control and experimental groups,” is better than “Researchers divided the subjects into control and experimental groups.” This is because passive voice emphasizes the object of the action rather than the subject. In scientific writing, the object is more important than the subject.

Advertisement -

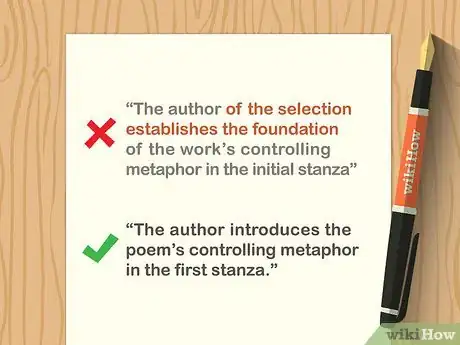

3Choose concise words and phrases. Cut out the fluff and keep your writing succinct. Whenever possible, choose a single word to make your point. Simple word choices are almost always better than convoluted phrases or repetitive adjectives and adverbs.[3]

- For example, “The author of the selection establishes the foundation of the work’s controlling metaphor in the initial stanza,” is packed with unnecessary words. A cleaner version of this example could be, “The author introduces the poem’s controlling metaphor in the first stanza.”

- Instead of “The animal sleeps during the day and is active at nighttime,” write “The animal is nocturnal.”

- Rather than "The fox ran very fast," write "The fox sprinted."

- In the sentence, “The argument is compelling and convincing,” compelling and convincing are close enough in meaning. Using one would get the point across, but using both is repetitive.

-

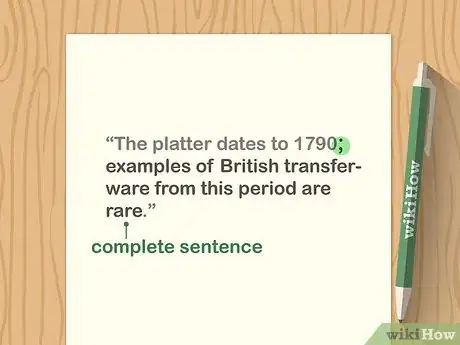

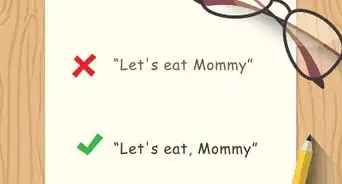

4Use punctuation to set your writing’s rhythm. Read out loud when you revise your work to fine tune your rhythm. Include commas to indicate brief pauses, periods for full stops, and semicolons for pauses between two independent clauses that are closely related. Use natural pauses to give a reader time to breathe, but don’t include so much punctuation that your writing feels choppy.

- Keep in mind the clause that follows a semicolon needs to be a complete sentence. It should also continue the idea conveyed in the clause before the semicolon. Proper use would be, “The platter dates to 1790; examples of British transfer-ware from this period are rare.”

- Use punctuation strategically. A complicated sentence, like this one, with too much, or confusing, or misplaced, punctuation is hard, for most readers, to follow. Aim instead for clear, easy-to-read writing.

-

5Vary your sentence structure. In addition to ensuring that your writing is easy to follow, you need to engage your readers. Sentences with varied rhythm and word order are more interesting than those with repetitive structures.[4]

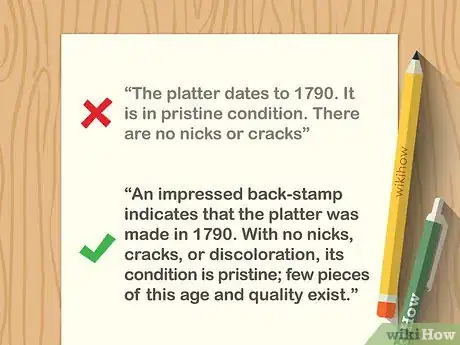

- For example, “The platter dates to 1790. It is in pristine condition. There are no nicks or cracks,” are choppy and repetitive.

- Better phrasing would be, “An impressed back-stamp indicates that the platter was made in 1790. With no nicks, cracks, or discoloration, its condition is pristine; few pieces of this age and quality exist.”

- Keep in mind repetitive sentences aren’t necessarily choppy. For instance, “Since the platter has a maker’s mark, accurately determining its age is possible. Since it has no nicks or marks, it is in excellent condition,” are repetitive sentences, even if they’re not short and choppy.

Using Academic Language

-

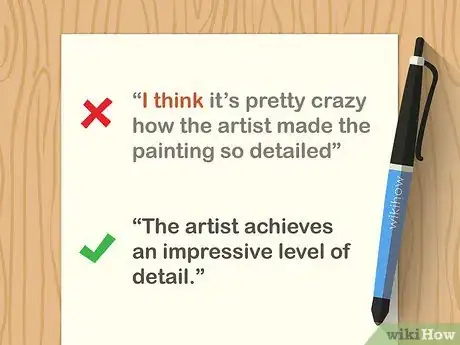

1Avoid slang, contractions, and other informal expressions. While academic writing needs to be clear and concise, it shouldn’t be casual. Spell out words such as “it is” instead of using contractions like “it’s.” Don’t use conversational words, such as “cool” or “pretty (as in “pretty interesting”), and write in the third person instead of using “I” or “me.”[5]

- For example, instead of, “I think it’s pretty crazy how the artist made the painting so detailed,” write, “The artist achieves an impressive level of detail.”

- Note that you can use the first person and contractions in less formal essays, such as an autobiographical sketch or college application essay. However, your writing still shouldn’t be too casual. “I found myself questioning my assumptions” is fine but, in most cases, “I was like wow I didn’t know what I was talking about” is too casual.

-

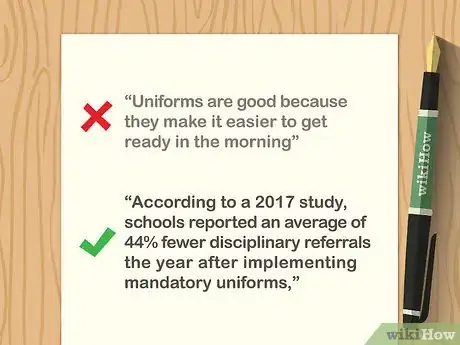

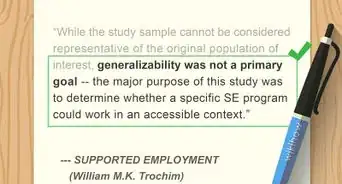

2Use objective, specific language instead of making generalizations. When crafting essays, support your claims with specific evidence and examples. Instead of merely stating your opinion, build your case on concrete facts.[6]

- Say you’re writing an essay about school uniforms. “Uniforms are good because they make it easier to get ready in the morning,” might be a fair point, but it's not the strongest argument you could make. Backing up your point with objective evidence would be more convincing.

- On the other hand, “According to a 2017 study, schools reported an average of 44% fewer disciplinary referrals the year after implementing mandatory uniforms,” cites a specific, concrete fact.

- Additionally, use specific quantities whenever possible. In this example, “an average of 44% fewer disciplinary referrals,” is more effective than “a significant decrease.”[7]

-

3Build your knowledge of your discipline’s vocabulary. Every subject has specific terminology. If you’re a student, check your textbooks for glossaries and chapter keyword lists. You can also search online for a subject, such as literature, plus “glossary” or “terminology.” Make flash cards to remember key terms, and note how they’re used in your textbook and in other scholarly works.[8]

- Learning how to properly use subject-specific terminology can help you express yourself clearly and effectively. Academic writing is a dialogue, and learning the language of a scholarly dialogue is essential.

- For instance, if you’re writing a literary analysis, you might discuss how an author makes a comparison. While technically correct, the word “comparison” isn’t as precise as literary terms such as “metaphor” or “simile.”

-

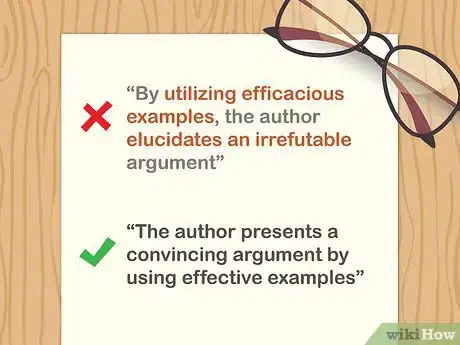

4Include big words and technical terms only when it’s necessary. While using your subject’s terminology properly is important, try not to go overboard. Expand your vocabulary, but don’t feel like you have to use big words to sound smart. Go with familiar terms instead of obscure ones, as long as doing so wouldn’t compromise precision and accuracy.[9]

- Using convoluted jargon or big words just for the sake of it will make your writing clunky. Furthermore, you’ll lose credibility if you misuse a complex word or technical term.

- For instance, “By utilizing efficacious examples, the author elucidates an irrefutable argument” is verbose. Simpler phrasing would be, “The author presents a convincing argument by using effective examples.”

Mastering the Writing Process

-

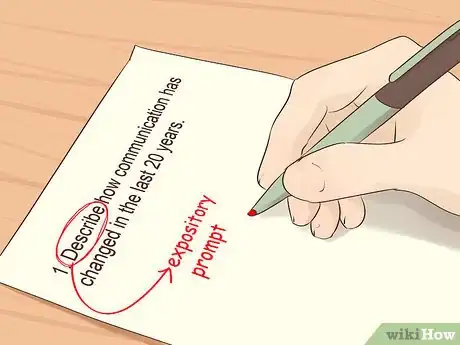

1Analyze your essay question or prompt. Carefully reading your prompt is the first step in the essay writing process. Make sure you clearly understand what your essay needs to accomplish. Circle or underline keywords, such as “analyze” or “compare and contrast.”[10]

- Note that an essay prompt’s keywords have distinct meanings. Analyze, for example, doesn’t mean to describe; it means to pull apart and examine something’s structure.

- Suppose you have to analyze an argument. Your essay needs identify the argument's rhetorical elements, such as pathos (appeals to emotion), logos (employing reason or logic), or ethos (relying on authority or credibility). After breaking down the argument's structure, you'll then need to explain how the author uses these devices to make their case.

-

2Research your subject matter. Once you understand your essay’s task, find credible sources on your topic. Examine primary sources, such as the poem you’re analyzing or letters written by the historical figure you’re discussing. Read what other scholars have argued, and identify how expert opinions on your topic vary.[11]

- Remember to check your sources’ credibility. If you’re writing about a former president, find the biography scholars consider most authoritative. Check the authoritative biography’s footnotes and references, which will help you track down more reputable sources.

- You won't conduct thorough research if you’re writing an essay for a test. Instead, read the sources provided with the exam. For example, if a literature essay test requires you to analyze an excerpt, read the passage carefully.

-

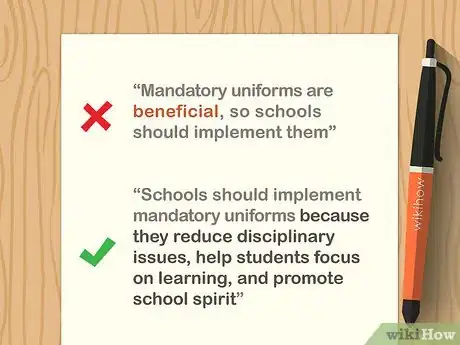

3Develop a succinct, arguable thesis. Once you’ve familiarized yourself with your topic, come up with an argument. Your thesis should be a concise sentence that tells readers what you plan to argue. Rather than vaguely generalize or state the obvious, an effective thesis makes a clear, defensible, and specific claim.[12]

- For instance, “Schools should implement mandatory uniforms because they reduce disciplinary issues, help students focus on learning, and promote school spirit,” is clear and specific.

- The thesis, “Mandatory uniforms are beneficial, so schools should implement them,” makes a claim, but “beneficial” is vague. It doesn’t convey why uniforms are good, so it’s not a strong thesis.

-

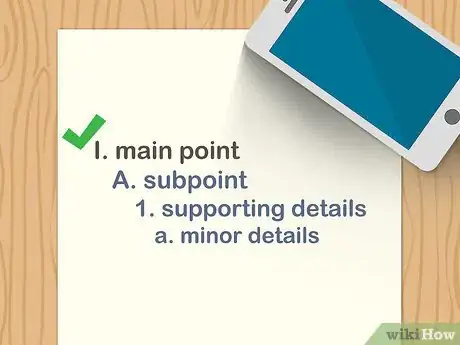

4Create an outline to map out your essay’s structure. The basic parts of an essay are an introduction, the body, and a conclusion. A good essay is well-organized, and each part transitions smoothly and logically to the next. To begin your outline, write the Roman number I., label it “Introduction” then, on the line below, write your thesis statement.[13]

- For the next Roman numerals, write the subtopics, citations, and other details that you’ll cover in each body paragraph.

- In the following example, Roman number II. would be an essay section, and letters A. through D. are body paragraphs that each focus on a sub-topic:

II. Uniforms reduce disciplinary issues

A. 44% decrease in detentions after introducing uniforms (Smith, 2017)

B. Suspension decreased by 60% (Smith, 2017)

C. Absenteeism and tardiness decreased (Pew, 2013)

D. 66% of students report less bullying (Ohio Board of Education, 2016)

-

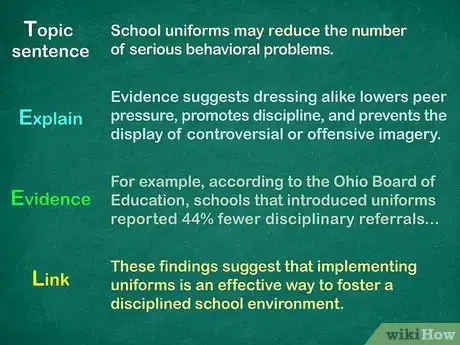

5Use the TEEL strategy to organize your paragraphs. TEEL stands for Topic sentence, Explain, Evidence or example, and Link, or refer to the essay’s main idea. If your sentences are logically connected, your argument will be clearer and more convincing. For example:[14]

- Topic sentence: School uniforms may reduce the number of serious behavioral problems.

- Explain: Evidence suggests dressing alike lowers peer pressure, promotes discipline, and prevents the display of controversial or offensive imagery.

- Evidence: For example, according to the Ohio Board of Education, schools that introduced uniforms reported 44% fewer disciplinary referrals, such as detentions and suspensions. Furthermore, 66% of surveyed students said they witnessed fewer bullying incidents after they started wearing uniforms.

- Link: These findings suggest that implementing uniforms is an effective way to foster a disciplined school environment.

-

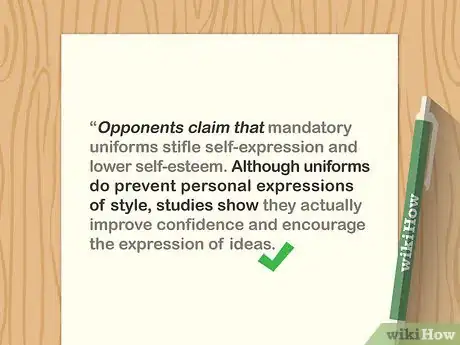

6Address a counterargument to strengthen your claim. Mention an argument that opposes your thesis, then explain why it’s incorrect. Be sure to bring up a strong counterargument. This is called a concession or rebuttal, and it strengthens your argument and shows you're unbiased. However, countering a weak argument that doesn’t actually represent the opposing side’s strongest claims will weaken your essay.

- A counterargument could be, “Opponents claim that mandatory uniforms stifle self-expression and lower self-esteem. Although uniforms do prevent personal expressions of style, studies show they actually improve confidence and encourage the expression of ideas. Rather than harm self-image, research suggests that uniforms positively impact mental health. In a 10-year Oxford University study, a majority of students reported that wearing uniforms boosts their self-esteem. With a level playing field, they worry less about choosing clothes that fit the norm.”

-

7Give yourself ample time to revise your draft. Time management is an essential aspect of essay writing. If you’re trying to rush through your essay right before it’s due, you won’t have time to edit it. Additionally, it’s helpful to step away for a few hours after writing so you can revise your work with fresh eyes.

- First, revise your essay’s content. Check for unclear language, unorganized spots, awkward sentences, and weak word choices. Next, proofread your work and fix any spelling or grammatical errors.

- For important essays, like a term paper or an admissions essay, have someone read your work and offer feedback.

- In general, try to leave a day for edits at the bare minimum. For a big research paper, scheduling a week or more is ideal.

- For a quick, paragraph-long assignment that’s due the next day, you might only need 15 or 20 minutes for revisions. If you're taking a timed essay test, set aside the last 5 to 10 minutes to check your work.

References

- ↑ https://www.extension.harvard.edu/inside-extension/cut-clutter-17-phrases-omit-your-writing-today

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/passive-voice/

- ↑ https://www.extension.harvard.edu/inside-extension/cut-clutter-17-phrases-omit-your-writing-today

- ↑ https://slc.berkeley.edu/nine-basic-ways-improve-your-style-academic-writing

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/sites/default/files/academic_style.pdf

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/sites/default/files/academic_style.pdf

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/sciences/

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/sites/default/files/vocabulary.pdf

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/sciences/

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/sites/default/files/Essay_writing_process_accessible_2015.pdf

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/sites/default/files/super%20essay.pdf

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/developing-thesis

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/essay-structure

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/content/paragraph-structure