This article was co-authored by Lahaina Araneta, JD. Lahaina Araneta, Esq. is an Immigration Attorney for Orange County, California with over 6 years of experience. She received her JD from Loyola Law School in 2012. In law school, she participated in the immigrant justice practicum and served as a volunteer with several nonprofit agencies.

There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 29,195 times.

Legal rules limit what kinds of questions a lawyer may ask a witness during trial. If the lawyer asks such a question, you need to object. There are many different objections you need to learn. If you are representing yourself in a trial, you want to commit several hours to learning the most common objections.

Steps

Raising an Objection

-

1Stand. It’s standard courtroom etiquette to stand when talking to the judge. Because you are addressing your objection to the judge, you probably want to stand when you raise an objection.[1] Sit with your chair slightly back from the table so that you can stand easily.

- Generally, you want to object before the witness answers a question.

- However, even if the witness has answered, you should still stand to object.

- Making your objection quickly is essential. Objecting too late means that the jury will have already heard the witness.

-

2State your objection. The proper format is to say “Objection” and then identify the specific objection. Sometimes people say only “objection,” but the judge wants you to identify why you are objecting. The standard form of an objection is as follows:

- “Objection, Your Honor. Leading question.”

- “Objection. Hearsay.” You don’t have to say “Your Honor” for every objection, but you should for some.

- The judge might also ask for lawyers to approach for a sidebar if the judge needs more information.

Advertisement -

3Speak loudly. Clear your throat so that you can speak clearly. You want everyone in the courtroom to be able to hear you. Breathe from your diaphragm. Remember to face the judge.[2]

- You might feel nervous. However, the more you talk in the court, the more comfortable you will feel.

- Avoid becoming angry. You want to sound forceful yet respectful.

-

4Ask for a sidebar if your objection is complicated. Sometimes you might need to go into greater detail about why you are objecting. It’s not appropriate to make a long legal argument within earshot of the jury, so you can ask the judge for a sidebar. Say, “May I approach the bench?”

- At the sidebar, both lawyers huddle with the judge. You can then go into greater detail why you think the question was improper.

- For example, the question might ask for privileged information the witness revealed to a lawyer or clergy member. You might need to give a four or five sentence explanation of why the communication was privileged.

- Don’t abuse sidebars. You don’t need a sidebar for every objection, and you shouldn’t request one simply because the judge ruled against you.

-

5Wait for the judge’s ruling. After you object, the witness shouldn’t answer. Instead, everyone must wait for the judge to rule. Typically, the judge will say either the following:[3]

- “Overruled” or “Objection overruled.”

- “Sustained” or “Objection sustained.”

- If the witness has already answered before you object, the judge will instruct the jury to disregard the witness’ answer if your objection is sustained.

-

6Listen closely to further questioning. Even if you win an objection, the lawyer might still try to ask the question later. Lawyers can be sneaky. You need to listen closely and object if the lawyer makes the same mistake again.

- It’s always important to object. On appeal, you can ask a higher court to review any mistakes the judge might have made. If you didn’t make an objection at trial, you lose the right to object on appeal.[4]

- This explains why you need to object even if the witness has just answered—you need to preserve the issue for appeal.

Learning Common Objections

-

1Identify leading questions. On direct examination, an attorney cannot ask their witness leading questions. A leading question is one that suggests its own answer.[5] Often, the witness can answer it with a “yes” or “no.” If the lawyer asks a leading question, stand and say, “Objection, Your Honor. Leading question.”

- For example, “You saw the defendant with the knife?” is a leading question. By contrast, “Who did you see holding the knife?” is not.

- “You were driving under the speed limit?” is a leading question. By contrast, “How fast were you driving?” is not.

- A lawyer can ask leading questions on cross-examination, so don’t object if that is the case.

-

2Pay attention to compound questions. A compound question is one that combines multiple parts as one question instead of breaking it down and asking each one separately. Listen closely and object if you hear a compound question by saying, “Objection. Compound question.”

- For example, “Did you pull into the gas station and fill up your tank with unleaded gas?” is compound. The lawyer should first ask, “What gas station did you go to?” and then ask, “What did you do there?”

-

3Focus on whether the lawyer exceeds the scope. On cross-examination, a lawyer can only ask questions that relate in some way to the testimony on direct examination. If the questioning doesn’t, then it exceeds the scope of permissible cross-examination. Object by saying, “Objection. Beyond the scope.”

- For example, a witness might testify on direct that she saw someone crash into her mailbox. On cross-examination, the attorney cannot start asking questions about her own driving record, since that has nothing to do with her direct testimony.

-

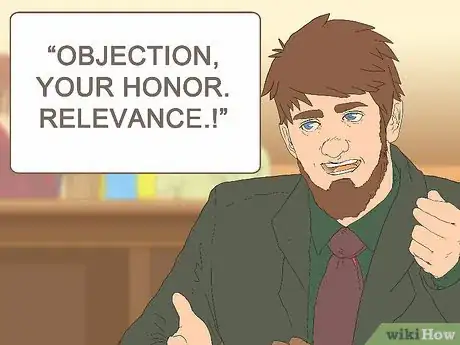

4Raise relevance objections. Questions must relate to the facts in dispute. For example, if a person is being prosecuted for drunk driving, they shouldn’t be asked about their credit card debt since that probably isn’t related.

- Object by saying, “Objection, Your Honor. Relevance.”

- Make sure the question truly isn’t relevant. Typically, a witness must lay a foundation for their testimony. For example, if a cop is testifying about pulling over a drunk driver, then he might testify as to when he started his shift. This testimony is relevant because it provides critical context.

- An expert witness also needs to prove they have expertise. Accordingly, a cop might need to talk about his training and experience.

-

5Identify objections when a lawyer is badgering a witness. Sometimes lawyer will hound a witness, particularly on cross-examination. There are a couple objections you could raise, depending on the circumstances:

- Asked and answered. A lawyer should only ask a question once and accept the witness’ answer. If a lawyer asks the question again, you can object. You can use this objection on both direct and cross-examination. Object by saying, “Objection. Asked and answered.”

- Badgering the witness. When a lawyer on cross-examination is being especially hostile, you should object. Always stand for this objection. Say, “Objection, Your Honor. Badgering the witness.”

-

6Object to assumptions made by the lawyer. Only witness testimony is evidence in a trial. Sometimes, lawyers try to slip in evidence through the questions they ask. For example, you should object to the following:

- Assumes facts not in evidence. The lawyer might ask a question containing a fact no one has testified to. For example, “After you heard the second gunshot, what did you do?” is improper if the witness never testified they heard a second gunshot. Object by saying, “Objection, Your Honor. Assumes facts not in evidence.”

- No foundation. A lawyer needs to establish certain facts before a witness can testify. For example, a witness needs to establish they were at a certain place and time before they testify as to what they saw. Also, a witness needs to establish what a document is before testifying as to its contents. When a witness just launches into their testimony without providing context, you should object. Object by saying, “Objection. Lack of foundation.”

-

7Watch out for narrative answers. On direct examination, some witnesses might not simply answer the question. Instead they will go on and on and on. You should object to these kinds of narrative answers. Say, “Objection, Your Honor. Narrative answer.”

- Often, hearsay slips out during a narrative answer or other inappropriate testimony. Accordingly, always raise an objection.

-

8Object to questions that ask for speculation. Witnesses can only testify as to what they observed. They can’t speculate about things. If you hear a speculative question, object: “Objection, Your Honor. Calls for speculation.”

- For example, a witness can testify that she saw someone driving erratically. However, a lawyer can’t ask, “Do you think the driver was drinking before they got in the car?” Unless the witness saw the driving drinking, she can’t speculate.

- By contrast, a witness may provide estimates based on their observation. A question like, “How tall did he look to you?” asks for the witness to guess since the witness didn’t have a measuring tape. However, this guess is based on personal observation and is therefore acceptable.

-

9Understand “hearsay.” Hearsay is second-hand testimony offered in court.[6] For example, a witness can testify that they saw a white car run a red light. However, it is hearsay for the witness to say, “My mother told me a white car ran a red light.”

- Here, the statement (what the mother said) is offered to prove what the white car did (go through a red light). The lawyer needs to call the mother as a witness to testify.

- Typically, hearsay occurs when someone testifies as to what another person told them outside of court. Listen for witnesses who say, “Someone told me” or “I heard from him that….” These are good signs they are about to offer hearsay.

- Some out-of-court statements are not considered hearsay. For example, any statement by the opposing party can be admitted into court. If you are suing someone, then a witness can testify as to what the defendant said. A witness can also testify about what you said.[7]

-

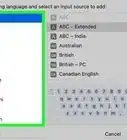

10Research other evidentiary rules. State and federal court have many other complicated evidentiary rules you should learn. These rules keep out certain types of testimony. You can find the Federal Rules of Evidence online.[8] Your state rules may also be online. In addition to hearsay, other inadmissible testimony includes:

- Unduly prejudicial statements. Testimony must be relevant. But its relevance also can’t be outweighed by its unfair prejudice. Unfairly prejudicial testimony often includes statements that a defendant has committed a crime or action before. Object by saying, “Objection, Your Honor. Unduly prejudicial.” You may also need a sidebar to go into greater depth.

- Privileged statements. Every state recognizes the attorney-client privilege. This means statements made to a lawyer for the purposes of obtaining legal advice cannot be disclosed without the client’s consent. There may be other privileges, such as a clergy privilege or a marital privilege. Object when a lawyer tries to uncover privileged communications.

- Impermissible testimony of a lay witness. Unlike an expert witness, a lay witness can only testify as to what they observed first-hand. They also can’t offer opinions based on technical or specialized knowledge.[9] Object when lay witnesses are asked questions that should be asked of an expert.

References

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPM9mD65W9M

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPM9mD65W9M

- ↑ http://litigation.findlaw.com/going-to-court/how-does-a-judge-rule-on-objections.html

- ↑ http://litigation.findlaw.com/going-to-court/how-does-a-judge-rule-on-objections.html

- ↑ http://criminal.findlaw.com/criminal-procedure/leading-questions.html

- ↑ https://www.legalzoom.com/articles/objection-hearsay-what-is-the-hearsay-rule-and-what-are-the-exceptions-to-it

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_801

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre

- ↑ https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_701