This article was co-authored by Meredith Brinster, PhD. Meredith Brinster serves as a Pediatric Developmental Psychologist in the Dell Children’s Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Program and as a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Dell Medical School of The University of Texas at Austin. With over five years of experience, Dr. Brinster specializes in evaluating children and adolescents with developmental, behavioral, and academic concerns, including autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, intellectual disability, anxiety, attention problems, and learning disabilities. Her current research focuses on early biomarkers of autism spectrum disorder, as well as improving access to care. Dr. Brinster received her BA in Psychological and Brain Sciences from Johns Hopkins University and her doctorate in Educational Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin. She completed her clinical internship in pediatric and child psychology at the University of Miami Medical School and Mailman Center for Child Development. She is a member of the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD) and the American Psychological Association (APA).

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 98% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 73,317 times.

If you are old enough to have an awareness of a complex neurological disability such as autism, you are old enough to tell your parents about anything. It may be hard, but it's worth it in the end. These steps will help guide you.

Steps

Doing Your Research

Autism is a multifaceted disability, and it takes a lot of research in order to understand.

-

1Learn about autism. Autism is a very complex and misunderstood disability, so it takes a lot of research to understand it. Read lists of traits and essays by autistic people. Autistic people are often the best source, because they have firsthand experience with how their brains work, and some stereotypes are wildly inaccurate. Signs of autism include:

- Unusual social behavior (such as accidentally saying rude things or laughing when inappropriate).

- May not want cuddling.

- Uneven physical or verbal skills. For example, poor handwriting or bad coordination.

- Avoidance of eye contact, staring, or unusual eye contact

- May need more alone time.

- Intense focus and large memory, especially when studying favorite things; may remember childhood well

- Difficulty with forming or understanding spoken words. May struggle with forming coherent sentences, and prefer written words, sign language, typing, or other forms of communication.

- Patterns of interest in specific subjects.[1]

- Preference of routines and sameness.[2]

- Remarkable honesty and loyalty.

- Idiosyncratic speech: echoing words or phrases,[3] flat or singsong tone of voice, unusual pitch, and/or artistic and abstract language.

- Exaggerated response or little response to sound, light, smell, taste, etc.

- Interest in how things work.

- Stimming behaviors (e.g. hand flapping, rocking, tapping pencils, hugging oneself, clapping hands, jumping, spinning, etc)

- Strong sense of justice and morality.

- Difficulty reading faces and interacting with others.

- Difficulty with social skills.[4]

- Difficulty understanding social relationships[5]

-

2Research carefully before making too many assumptions. Reading one article on autism isn't enough to get a good sense. Read the diagnostic criteria, delve into the Autistic community online, and read how autistics describe autism. Reflect as you read. Does it fit you?

- Research related and co-occurring conditions. Is it possible that you have any of these in addition to autism, or instead of autism?

- Keep in mind that autism is not perfectly understood. There is still misinformation out there, and there are studies with contradictory and unclear conclusions. Some information is written by non-autistic people who never consulted any autistics, and thus may have gotten something wrong.

Tip: Even if autism seems likely, don't get too attached to the diagnosis. You don't want to become so single-minded that you overlook the truth. For example, a combination of ADHD and NVLD can look a lot like autism. You want an accurate diagnosis.

Advertisement -

3Learn about conditions that could be mistaken for autism. ADHD, reactive attachment disorder, social anxiety, avoidant personality disorder, OCD, and schizophrenia are examples of disabilities that can look somewhat similar to autism.[6]

- It's possible to be autistic and have one of these disabilities. For example, it isn't uncommon for autistic people to have ADHD.

-

4Reflect upon what you've read. Think back on your childhood, your quirks, your needs, and the accommodations that you and others make for you. When you consider autism, do things start to make more sense? Or is it a poor fit?

-

5Consider your childhood and your earliest memories. Did you walk in circles, line up your toys, or make unusual repetitive movements? Did you hit your milestones in an unusual order? (This includes early childhood, and also later childhood, such as learning to ride a bike or swim.) Reflect on your childhood and see if autism explains any of your quirks, strengths, or struggles.

-

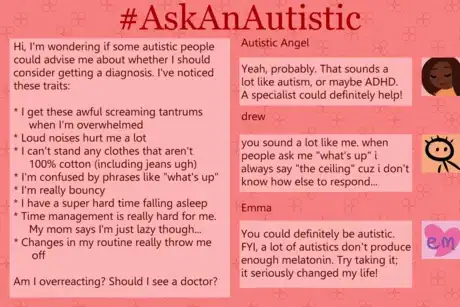

6Talk to real autistic people. Visit a disability club, read blogs, or use #AskAnAutistic/#AskingAutistics to ask about autism. You can even talk about the autistic traits you've noticed in yourself, and ask if they think it's a possibility.

Talking to Your Parents

-

1Choose a calm, quiet time to talk. You'll want a time when no one is especially stressed or distracted. Try a time like doing simple chores together, a long car ride, or cleaning up after dinner.

- If your parents are moving quickly, being louder than usual, or being short with you, that means they are probably stressed and not ready to listen.

- Avoid times of extra stress, like when someone is sick, a big family transition (e.g. right before a vacation), or holidays with relatives over. Your parents may not be as focused, and have a hard time listening well.

-

2Use "process talk" to explain that you have something important to say. You can say something like "I have something big to tell you, and I'm wondering if now is a good time."

-

3Explain that you think there's a possibility you're autistic. Give some examples of your unusual behavior and experiences. Let them know that you've been thinking about this carefully and that finding answers is important to you.

- For example, "I think I could be autistic. I've been researching it for the past month, and a lot of the qualities describe me—meltdowns, sensitivity to sound, difficulty understanding others' thoughts and feelings, and fidgeting, for example. I've put a lot of thought into this and it's helped me understand myself better."

- Describe the traits that are most noticeable in you, especially that others can notice. For example, you lining up your things and having meltdowns may be easier for others to see than your face blindness. Bring up the most obvious ones first.

Tip: You don't have to get your parents to agree that you're probably autistic today. All you need to do is convince them that it's worth bringing up with a doctor or specialist.

-

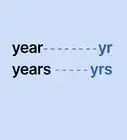

4Use tentative language. If you show that you're open-minded about various possibilities, your parents are more likely to be open-minded too. Instead of saying you're sure you're autistic, say that you think it's possible.

- You may have done weeks or months of detailed research, and thus be used to the idea. However, your parents are likely hearing this for the first time. If you sound uncertain, they're less likely to give a knee-jerk "no" response, and they'll take the possibility more seriously.

-

5Focus on the benefits of looking into it. Describe how a diagnosis, and the subsequent support, could help you. Your parent(s) want what's best for you, so focus on how seeing a specialist could improve your life. Here are some examples of the benefits of a diagnosis:

- You could learn diagnosis-specific techniques for reducing stress in your life, making you more comfortable and calm.

- You could do better in school due to getting accommodations, which could improve your grades, enhance your understanding of the material, and/or reduce stress.

- You could get therapy focused on your specific challenges (e.g. sensory integration therapy).

- You and your parents would have access to a supportive community of autistics and their loved ones.

-

6Be prepared to correct common misconceptions. Many people don't know much about autism, and rely on stereotypes that don't match autistic people in general, including you.

- Many autistic people are able to speak.

- Autistic people do care about others, often quite deeply. Many autistics have empathy. However, not all of them know how to show this in ways that others understand.

- Autism is not a childhood disability. It is lifelong. There is no "cure."

- Autism is not limited to white boys. People of all ethnicities, ages, and genders can be autistic.

- Autism is not an epidemic. It isn't contagious, the word "epidemic" is misleading, and autistic people have many unique gifts to offer the world.

- Each autistic person is different. Some need a lot of support, while others go for decades without knowing why they're different. The degree to which they have different symptoms may vary.

- People with autism don't want friends or don't have friends.[9]

-

7Tell a strongly resistant parent how you seeing a doctor would benefit them. Getting care for a disability can be tough if your parents are abusive, neglectful, or otherwise bad. If your parents are dismissive or cruel to you, focus on how their life might be improved by you getting a diagnosis.

- For a parent who is annoyed by specific traits you have, such as meltdowns: "A therapist could help me avoid meltdowns, so then I wouldn't be crying and making a scene so much."

- For a self-absorbed parent: "Parents are really important in the diagnosis process. I bet they'd want to interview you. After all, you're the expert on what I was like in childhood."

- For a parent who is tired of you asking about autism: "If we finally got answers, I wouldn't have to keep wondering why I'm different."

Tip: If they don't believe you after some time, you do have other options. Go to a school counselor or other trusted adult and explain the situation. They may be able to talk to your parent(s). Once it's time for your doctor check-up, you can also explain to the doctor that you think there's a chance you're autistic.

-

8Give your parents time to process this. This is big news, and your parents may need time to absorb it. They may also not understand what autism is very well. Do your best to be patient with them if they react badly. It's not personal; they're just confused.

-

9Ask to see a doctor or specialist. Your general practitioner or insurance company may be able to refer you to an autism expert, who can officially evaluate you for autism and related conditions.[10]

- If your parents are skeptical, you can explain that seeing a specialist would clear things up.

- The diagnosis process is not perfect, and can rely on your ability to produce anecdotes about certain traits you do or don't have. Being prepared for your appointment can help you get a more accurate diagnosis.

Warnings

- Look out for anti-autism groups such as Autism Speaks when you research. Some organizations label themselves charities while spreading destructive rhetoric. This is not a reflection of you, and you have every right to ignore them.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.

- ↑ http://musingsofanaspie.com/2013/09/18/echolalia-thats-what-she-said/

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/brain/autism/other-conditions-with-symptoms-similar-to-autism

- ↑ https://misslunarose.home.blog/2021/02/21/dsm-5-autism-quiz/

- ↑ https://misslunarose.home.blog/2020/02/25/steve-asbell-aq-r/

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Meredith Brinster, PhD. Licensed Clinical Psychologist. Expert Interview. 23 July 2021.