This article was co-authored by Travis Page. Travis Page is the Head of Product at Cinebody. Cinebody is a user-directed video content software company headquartered in Denver, Colorado that empowers brands to create instant, authentic, and engaging video content with anyone on earth. He holds a BS in Finance from the University of Colorado, Denver.

This article has been viewed 84,079 times.

A scene is the building block of a larger story. Commonly, scenes are used to describe the parts of a play or film script. However, a "scene" refers to any discrete event, meaning it has a beginning and end, whether you're writing a novel or a future movie. Scenes must generally have an arc, characters, and take place in a single setting. Scenes become the puzzle pieces of your larger work, so learning to get them right now will make your final book or script that much better.

Note: This article is about the theory and writing of a great scene. For help formatting a scene for a script or play, click here.

Steps

Setting the Scene

-

1Determine what the scene needs to say or accomplish. You need to know what your scene adds to the larger work. A scene should be able, in large part, to stand on its own as a mini-story. Your characters, and the reader, need to be at a different place at the end of the scene than the beginning. If you haven't shown growth or exposed something new to the audience then the scene likely isn't necessary. The best scenes accomplish many things at once, often very subtly. Common uses for a scene include:[1]

- Moving the plot forward.

- Establishing or resolving conflict/tension.

- Illuminating new character traits.

- Showing how characters have changed.

- Exposing or illustrating a new location or new character.

- Telling a joke or hitting an important emotional beat.

-

2Choose the characters that you need for the scene. Once you know what the scene needs to accomplish, you need to find out who needs to be there to accomplish it. If you're writing a screenplay or script, you want as few characters as you need. You may not notice a character hasn't spoken in five minutes on the page, but you will notice them sitting around silently on stage. Remember that, while you want your characters to behave realistically, you still need your scene to accomplish it's goal. Instead of bending a character to fit your plot, leave them out of the scene or find a way to make them fit into the scene without betraying their character.[2]

- If you're writing a stand-alone scene, like a skit, spend some time brainstorming characters. You might write out a few sentences, or do a full character sketch.

Advertisement -

3Find an interesting or exciting setting for the scene. Try to think of something beyond the obvious for the best results. What kind of location would best highlight your conflict, tension, or theme? Where can you believably set the character while still exposing new sides of them. Oftentimes, the setting you choose provides conversation topics for your characters, especially in the beginning of the scene. You can try and make a slight metaphor between the location and the actual scene, such as Invisible Man's famous, metaphorical white paint factory scene playing on "white-washing" race relations.

- While most dates take place in a park or at a nice restaurant, Rocky's famous courtship scene is extra powerful because it is in an abandoned ice-skating rink, which mimics the shape and feel of a boxing ring.

- The violent ending of There Will Be Blood is extra shocking because it takes place in the most innocent setting of the entire movie -- a home bowling alley.

- The turning point of the North Korean set Orphan Master's Son takes place in Texas, putting the characters in perhaps the least North Korean location imaginable to spur their rebellion.[3]

-

4Start the scene with a strong hook. You want your first lines of the scene to pull the reader immediately in. Oftentimes, writers have the first line or two of the scene already in their head, spurring them on to write. But that doesn't mean the first choice is necessarily the best. Write down 4-5 different openings, keeping in mind your goals for the scene, and then move forward from your favorite.[4]

- How many lines can you cut at the very beginning of the scene before you get to essentials? It's best to dive right into the story instead of following your character through a normal day.

-

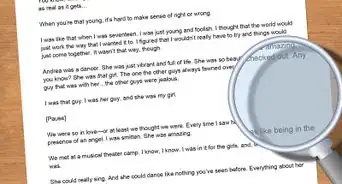

5Sketch the scene out roughly by hand. Free yourself from perfection and just take off writing. Once you have an opening, even one you're not sure you want to keep, write out the scene quickly as it comes to you. Let your characters speak and react to the position you put them in, even if it doesn't conform to your original plan. Take a detour or unleash a surprise on your characters during a moment of inspiration. Remember that this is just a quick draft. You will pick and choose the best moments later on.

- The goal is to start visualizing the scene, playing the movie or novel in your head as you write.[5]

-

6Build your scenes around action and events, not thoughts. Monologues are not scenes, and neither are philosophical discussions. Both have their place in movies and books, but they don't have their place in scenes. When writing scenes, you need to think in concrete terms, letting tangible events shape the scene and propel your characters and plot forward. Even a good conversation can be a scene, as conversation can reveal surprising insights and trigger new events. However, a middling conversation between two best friends that doesn't show us anything new is not a scene. Some tips include:

- Thinking in terms of action and reaction, not random chance, to make more dynamic scenes.

- Leading with the action. If someone thinks about doing something, then does it, like hitting a character, start with the punch first. Then follow up with "she'd wanted to do that for a long time."

- Revealing inner thought through action. Hemingway was a master of this, using small actions to show bigger emotions. For example, a character leaning back in a chair suddenly leans forward, putting all four chair legs down, as he has just heard news of his long-lost lover, who he pretends not to know, in "The Big Two-Hearted River.[6]

Writing Effective Scenes in Any Format

-

1Find the scene's central conflict. The general arc of the scene, or how it changes from beginning to end, is the most obvious layer of a scene. But underneath that layer, in all good scenes, is conflict. At its most basic level, conflict is the difference between what a character wants (money, love, power, a steak) and what he/she can get. Conflict is usually between two characters, and is often not talked about out loud. But you need to identify it as a writer and find a way to incorporate it into the scene every time.

- Shakespeare was the master of hidden conflict. Look, for example, at Macbeth, who as the reader knows, is hiding a murderous guilt under every act of kindness or political speech.

- Conflict is often created out of character traits. On Parks and Recreation, we know that libertarian Ron Swanson hates the Federal Government. This makes his decision to ask for a job at the US National Parks Service in one scene much more poignant.

- Conflict does not have to immediately resolve. Every scene of Memento is built upon a conflict between what we remember and what we think we remember. Each scene plays subtly between the two opposing sides.

-

2Choose the "third option" to surprise readers. In most scenarios, characters face two choices. They might marry the girl, or remain single; save the town or retreat to safety; take the big promotion, or stay with their family, etc. But the real world is not so black and white. The most effective scenes set up this dichotomy and then abandon it for a completely surprising and more satisfying third option. This could be a new plan, a compromise, or even a disaster that ruins or changes everything. Not every scene should choose the "third options." Still, try to keep your mind open to alternatives when writing.

- Of course, the "third option" could be the fourth or fifth option. The larger goal is to choose something hidden or unsuspecting, instead of the obvious outcome.

- Make a list of 25 different endings or options, even dumb or improbable ones, if you get stuck.

-

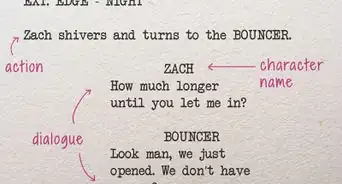

3Make your characters speak in unique, differentiated voices. You want your characters to sound vibrant and different from one another. If you were to remove all of the dialog tags, such as "Maggie said" or "DAVE:", you should still be able to tell who is actually talking. The better you know your characters, the easier it will be.

- Slang, expressions, accents, and even punctuation are good ways to differentiate characters' voices.

-

4Use details and descriptions to help with pacing. When you add details, like the color of the room or the people passing outside, use them to slow down the pace and give the scene some room to breathe. For example, instead of writing, "they sit in silence," take some time to describe what the characters do with their silence. What do they look at, smell, touch, or think?

- Details are best when the reflect the inner lives of characters. For example, a sad character is likely to notice an abandoned storefront. They might not notice the happy people at the cafe, or they could complain about how happy everyone looks.

- In general, scripts and plays should only have the essential details. If you want silence or calm moments, show it in your action lines, such as "he pours his coffee silently."[7]

-

5Reread the scene through each character's perspective. Some writers even draft up short versions of the scene from different perspectives. The goal is to ask yourself if each character is behaving realistically. If your audience can stand up and say -- "that person would never do that," you'll deflate the energy from the scene instantly. Find ways to get believable reactions that are true to each character and the scene will shine.

-

6Cut the scene to bare bones. This is often the hardest part of writing a scene, but it is absolutely crucial. Readers bring their imaginations to the scene, filling in the smaller details and even the tone of voice. The temptation to put your exact vision for the scene is strong, but is ultimately impossible. Instead, let your reader fill in the gaps. Most importantly, this makes your real moments shine even brighter when left on their own.[8]

-

7Ask yourself if the scene is essential to the larger story. Ignore whether your like the scene or not, whether it is hilarious or heart-wrenching. If you removed the scene, would the larger plot of the story change in any way? If not, then you may want to remove the scene altogether. Save the funny bits or the beautiful monologues and see if they can fit into other, more useful scenes. Ultimately, if the scene is just spinning its wheels, you'll get more mileage out of these little snippets in more powerful scenes.[9]

Sample Scene from Play

Expert Q&A

Did you know you can get expert answers for this article?

Unlock expert answers by supporting wikiHow

-

QuestionWhen should you storyboard? What's the point of storyboarding?

Travis PageTravis Page is the Head of Product at Cinebody. Cinebody is a user-directed video content software company headquartered in Denver, Colorado that empowers brands to create instant, authentic, and engaging video content with anyone on earth. He holds a BS in Finance from the University of Colorado, Denver.

Travis PageTravis Page is the Head of Product at Cinebody. Cinebody is a user-directed video content software company headquartered in Denver, Colorado that empowers brands to create instant, authentic, and engaging video content with anyone on earth. He holds a BS in Finance from the University of Colorado, Denver.

Brand & Product Specialist You typically craft your storyboard after you've locked the idea for the story down. You can also write the script before doing the storyboard, although you can also make your storyboard while you're writing the script. The goal of storyboarding is to create the vision for your production. It helps guide how you set each scene up and gives you something to work off of when it comes to the production itself.

You typically craft your storyboard after you've locked the idea for the story down. You can also write the script before doing the storyboard, although you can also make your storyboard while you're writing the script. The goal of storyboarding is to create the vision for your production. It helps guide how you set each scene up and gives you something to work off of when it comes to the production itself.

References

- ↑ http://www.timothyhallinan.com/writers.php?id=20&mode=chapter&partid=3

- ↑ http://johnaugust.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/how-to-write-a-scene.pdf

- ↑ http://www.thecreativepenn.com/2011/08/17/how-i-write-a-scene/

- ↑ http://www.advancedfictionwriting.com/articles/writing-the-perfect-scene/

- ↑ http://johnaugust.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/how-to-write-a-scene.pdf

- ↑ http://www.writersdigest.com/whats-new/10-ways-to-launch-strong-scenes

- ↑ http://www.thecreativepenn.com/2011/08/17/how-i-write-a-scene/

- ↑ http://www.advancedfictionwriting.com/articles/writing-the-perfect-scene/

- ↑ http://johnaugust.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/how-to-write-a-scene.pdf

About This Article

To write a scene, start by determining what the main goal or action of the scene needs to be. Next, choose the characters that you need for the scene and pick an interesting or exciting setting to highlight the action or theme. Once you’re ready to start writing, begin with a strong hook to pull the reader in quickly, then sketch the rest of the scene out roughly. As you work on the scene, make sure you have a general arc to the action, including a central conflict. To learn how to add appropriate details and descriptions to your scene, keep reading!