Angels in Islam

In Islam, angels (Arabic: ملاك٬ ملك, romanized: malāk; plural: ملائِكة, malāʾik/malāʾikah)[1] are believed to be heavenly beings, created from a luminous origin by God (Allah).[2][3] Although Muslim authors disagree on the exact nature of angels, they agree that they are autonomous entities with subtle bodies.[4]: 508 Yet, both concepts of angels as anthropomorphic creatures with wings and as abstract forces are acknowledged.[5]

The Quran is the principal source for the Islamic concept of angels,[5] but more extensive features of angels appear in hadith literature, Mi'raj literature, Islamic exegesis, theology, philosophy, and mysticism.[2][3][6] Belief in angels is one of the main articles of faith in Islam.[7] The angels differ from other spiritual creatures in their attitude as creatures of virtue, in contrast to evil and or ambiguous jinn.[2][8]

Angels are more prominent in Islam compared to Judeo-Christian tradition.[9] Angels play an important role in Muslim everyday life by protecting the believers from evil influences and recording the deeds of humans. They have different duties, including their praise of God, interacting with humans in ordinary life, defending against devils (shayāṭīn) and carrying on natural phenomena.[3] Angelic qualities, just as devilish ones, are assumed to be part of human's nature, the angelic one related to the spirit (ruh) and reason ('aql), while the devilish one to egoism.[10] Angels might accompany aspiring saints or advise pious humans. Angels are believed to be attracted to clean and sacred places.

Islamic Modernist scholars such as Muhammad Asad and Ghulam Ahmed Parwez have suggested a metaphorical reinterpretation of the concept of angels.[11] Adherents to the Salafi methdology stick to a literal belief in the existence of angels, but nonetheless, have a less vivid imagination of angels, their individuality, and their interactions with the human world in general compared to traditional Islamic thought.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Etymology

The Quranic word for angel (Arabic: ملك, romanized: malak) derives either from Malaka, meaning "he controlled", due to their power to govern different affairs assigned to them,[12] or from the triliteral root '-l-k, l-'-k or m-l-k with the broad meaning of a "messenger", just as its counterpart in Hebrew (malʾákh). Unlike the Hebrew word, however, the term is used exclusively for heavenly spirits of the divine world, as opposed to human messengers. The Quran refers to both angelic and human messengers as rasul instead.[13]

Characteristics

In Islam, angels are heavenly creatures created by God. They are considered older than humans and jinn.[14] Contrary to popular belief, angels are never described as agents of revelation in the Quran, although exegesis credits Gabriel with that.[15]

One of the Islamic major characteristic is their lack of bodily desires; they never get tired, do not eat or drink, and have no anger.[16] As with other monotheistic religions, angels are characterized by their purity and obedience to God.[17] In Islamic traditions, they are described as being created from incorporeal light (Nūr).[18][19][lower-alpha 1] A narrative transmitted from Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, audited and commented by two hadith commentary experts in the modern era, Shuaib Al Arna'ut[28] and Muḥammad 'Abd ar-Raḥmān al-Mubarakpuri,[29] has spoken a hadith that Muhammad said the number of angels were countless, to the point that there is no space in the sky as wide as four fingers, unless there is an angel resting his forehead, prostrating to God.[29][28]

Humans and angels

Muslim scholars have debated whether human or angels rank higher. Angels usually symbolize virtuous behavior, while humans have the ability to sin, but also to repent. Humans are considered to be able to reach a higher level than angels due to their ability to choose to avoid sin. The prostration of angels before Adam is often seen as evidence for humans' supremacy over angels. Others hold angels to be superior, as being free from material deficits, such as anger and lust. Angels are free from such inferior urges and therefore superior, a position especially found among Mu'tazilites and some Asharites.[30] A similar opinion was asserted by Hasan of Basri, who argued that angels are superior to humans and prophets due to their infallibility, originally opposed by both Sunnis and Shias.[31] This view is based on the assumption of superiority of pure spirit against body and flesh. Maturidism generally holds that angels' and prophets' superiority and obedience derive from their virtues and insights to God's action, but not as their original purity.[32]

Contrarily argued, humans rank above angels, since for a human it is harder to be obedient and to worship God, hassling with bodily temptations, in contrast to angels, whose life is much easier and therefore their obedience is rather insignificant. Islam acknowledges a famous story about competing angels and humans in the tale of Harut and Marut, who were tested to determine, whether or not, angels would do better than humans under the same circumstances,[33] a tradition opposed by some scholars, such as ibn Taimiyya, but still accepted by others, such as ibn Hanbal.[34] It seems that humans' quality of obedience and temptations mirrors that of angels: In the Quran, Adam fell from God's favor for his wish to be like the angels, while a pair of angel is said to have fallen for their desire for human lust.[35] In a comment of Tafsir al-Baydawi it is said that the angels' "obedience is their nature while their disobedience is a burden, while human beings' obedience is a burden and their hankering after lust is their nature.[4]: 546

Andalusian scholar ibn Arabi argues that a human generally ranks below angels, but developed to Al-Insān al-Kāmil, ranks above them.[36] This reflects the major opinion that prophets and messengers among humans rank above angels, but the ordinary human below an angel, while the messengers among angels rank higher than prophets and messengers among humans.[30] Ibn Arabi elaborates his ranking in al-Futuhat based on a report by Tirmidhi. Accordingly, Muhammad intercedes for the angels first, then for (other) prophets, saints, believers, animals, plants and inanimate objects last, this explaining the hierarchy of beings in general Muslim thought.[37]

Groups of modern scholars from Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University in Yemen and Mauritania issued fatwa that the angels should be invoked with blessing Islamic honorifics (ʿalayhi as-salāmu), which is applied to human prophets and messengers.[38] This fatwas were based on the ruling from Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya.[38]

Impeccability

The possibility and degree of erring angels is debated in Islam.[39] Hasan of Basra (d. 728) is often considered one of the first who asserted the doctrine of angelic infallibility. Others accepted the possibility of fallible angels, such as Abu Hanifa (d. 767), who ranked angels based on their examples in the Quran.[40]

The Quran describes angels in al-Tahrim (66:6) "not disobeying" and in al-Anbiya "not acting arrogant", which served as a base for the doctrine of angelic impeccability. Others argue that, if angels couldn't sin, it wouldn't be necessary to compliment them for their obedience.[4]: 546 Similarly al-Anbiya (21:29) stresses out that if an angel were to claim divinity for himself, he would be sentenced to hell, implying that angels might commit such a sin.[32][41] This verse is generally associated with Iblis (Satan), those nature (angel, jinn, or devil) is likewise up to debate. The presence of two fallen angels referred to as Harut and Marut, further hindered their complete absolution from potentially sinning.[4]: 548 [42]

To defend the doctrine of angelic impeccability, al-Basri already reinterpreted these verses and argued that Harut and Marut were human kings but not angels. Likewise, he was a strong advocate for rejecting Iblis' angelic origin.[43] His approach is by no means universally accepted among Muslim scholars. Unlike philosophers, most mutakallimūn accept to a certain degree that angels might err. Fakhr al-Din al-Razi is an exception and agrees with the Mu'tazilites that angels can't sin. He goes further and includes to the six articles of faith not only belief in angels, but one must also believe in their infallability.[44]

Al-Maturidi (853–944 CE) pointed at verses of the Quran, according to which angels are tested by God and concludes angels have free-will, but, due to their insights to God's nature, choose to obey. Some angels nevertheless lack this insight and fail.[32] Al-Baydawi asserts that "certain angels are not infallible even if infallibility is prevalent among them — just as certain human beings are infallible but fallibility is prevalent among them."[4]: 545 Al-Taftazani (1322 AD –1390 AD) agrees with al-Basri that angels wouldn't become unbelievers, such as Iblis did, but accepted they might slip into error and become disobedient, like Harut and Marut.[45] Most scholars of Salafism reject accounts on erring angels entirely and do not investigate this matter further.[46]

Purity

Angels believed to be engaged in human affairs are closely related to Islamic purity and modesty rituals. Many hadiths, including Muwatta Imam Malik from one of the Kutub al-Sittah, talk about angels being repelled by humans' state of impurity.[47]: 323 Such angels keep a distance from humans, who polluted themselves by certain actions (such as sexual intercourse). However, angels might return to an individual as soon as the person (ritually) purified themselves. The absence of angels may cause several problems for the person. If driven away by ritual impurity, the Kiraman Katibin, who record people's actions,[47]: 325 and the Guardian angel,[47]: 327 will not perform their tasks assigned to the individual. Another hadith specifies, during the state of impurity, bad actions are still written down, but good actions are not. When a person tells a lie, angels nearby are separated from the person from the stench the lie emanates.[47]: 328 Angels also depart from humans when they are naked or are having a bath out of decency, but also curse people who are nude in public.[47]: 328

Some scholars assert that such circumstances might interfere with an angels' work and thus impede their duty. For example, dogs, unclean places, or something confusing them might prevent them from entering a home.[48][49][50][51]

The al-Sahifa al-Sajjadiyya, a book of prayers attributed to Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin, contains a chapter praying for blessings for the angels.[52]

In philosophy

Inspired by Neoplatonism, the medieval Muslim philosopher Al-Farabi developed a cosmological hierarchy, governed by several Intellects. For al-Farabi, human nature is composed of both material and spiritual qualities. The spiritual part of a human exchanges information with the angelic entities, who are defined by their nature as knowledge absorbed by the Godhead.[53] A similar function is attested in the cosmology of the Muslim philosopher Ibn Sina, who, however, never uses the term angels throughout his works. For Ibn Sina, the Intellects have probably been a necessity without any religious connotation.[54]

Muslim theologians, such as al-Suyuti, rejected the philosophical depiction on angels, based on hadiths stating that the angels have been created through the light of God (nūr). Thus angels would have substance and could not merely be an intellectual entity as claimed by philosophers.[55]

The chain of being, according to Muslim thinkers, includes minerals, plants, animals, human and angels. Muslim philosophers usually define angels as substances endowed with reason and immortality. Humans and animals are mortal, but only men have reason. Devils are unreasonable like animals, but immortal like angels.[56][57]

Sufism

Unlike kalām (theology), Sufi cosmology usually makes no distinction between angels and jinn, understanding the term jinn as "everything hidden from the human senses". Ibn Arabi states: "[when I refer to] jinn in the absolute sense of the term, [I include] those which are made of light and those which are made of fire."[59] While most earlier Sufis (like Hasan al-Basri) advised their disciples to imitate the angels, Ibn-Arabi advised them to surpass the angels. The angels being merely a reflection of the Divine Names in accordance within the spiritual realm, humans experience the Names of God manifested both in the spiritual and in the material world.[60]

Just as in non-Sufi-related traditions, angels are thought of as created of light. Al-Jili specifies that the angels are created from the Light of Muhammad and in his attribute of guidance, light and beauty.[61] Influenced by Ibn Arabi's Sufi metaphysics, Haydar Amuli identifies angels as created to represent different names/attributes of God's beauty, while the devils are created in accordance with God's attributes of Majesty, such as "The Haugthy" or "The Domineering".[62]

The Sufi Muslim and philosopher Al Ghazali (c. 1058–19 December 1111) divides human nature into four domains, each representing another type of creature: animals, beasts, devils and angels.[63] Traits human share with bodily creatures are the animal, which exists to regulate ingestion and procreation and the beasts, used for predatory actions like hunting. The other traits humans share with the jinn[lower-alpha 2] and root in the realm of the unseen.

Angels as companions

In later Sufism, angels are not merely models for the mystic but also their companions. Humans, in a state between earth and heaven, seek angels as guidance to reach the upper realms.[60] Some authors have suggested that some individual angels in the microcosmos represent specific human faculties on a macrocosmic level.[65] According to a common belief, if a Sufi can not find a sheikh to teach him, he will be taught by the angel Khidr.[66][67] The presence of an angel depends on human's obedience to divine law. Dirt, depraved morality and desecration may ward off an angel.[60]

Ahmad al-Tijani, founder of the Tijaniyyah order, narrates that angels are created through the words of humans. Through good words an angel of mercy is created, but through evil words an angel of punishment is created. By God's degree, if someone repents from evil words, the angel of punishment may turn into an angel of mercy.[68]

Angels and devils

According to al-Ghazali, humans consist of animalistic and spiritual traits. From the spiritual realm (malakut), the plane in which symbols take on form, angels and devils advise the human hearth (qalb).[69] However, the angels also inhabit the realm beyond considered the realm from which reason ('aql) derives from and devils have no place.

While the angels endow the human mind with reason, advices virtues and leads to worshipping God, the devil perverts the mind and tempts to abusing the spiritual nature by committing sins, such as lying, betrayal, and deceit. The angelic natures advices how to use the animalistic body properly, while the devil perverts it.[70] In this regard, the plane of a human is, unlike whose of the jinn and animals, not pre-determined. Humans are potentially both angels and devils, depending on whether the sensual soul or the rational soul develop.[71][72]

In Salafism

Contemporary Salafism continues to regard the belief in angels as a pillar of Islam and regards the rejection of the literal belief in angels as unbelief and an innovation brought by secularism and Positivism. Modern reinterpretations, as for example suggested by Nasr Abu Zayd, are strongly disregarded. Simultaneously, many traditional materials regarding angels are rejected on the ground, they would not be authentic. The Muslim Brotherhood scholars Sayyid Qutb and Umar Sulaiman Al-Ashqar reject much established material concerning angels, such as the story of Harut and Marut or naming the Angel of Death Azrail. Sulayman Ashqar not only rejects the traditional material itself, he furthermore disapproves of scholars who use them.[73]

Classification of angels

Islam has no standard hierarchical organization that parallels the division into different "choirs" or spheres hypothesized and drafted by early medieval Christian theologians, but generally distinguishes between the angels in heaven (karubiyin) fully absorbed in the ma'rifa (knowledge) of God and the messengers (rasūl) who carry out divine decrees between heaven and earth.[74][75] Others add a third group of angels, and categorize angels into İlliyyûn Mukarrebûn (those around God's throne), Mudabbirât (carrying the laws of nature), and Rasūl (messengers).[76] Since angels are not equal in status and are consequently delegated to different tasks to perform, some authors of tafsir (mufassirūn) divided angels into different categories.

Al-Baydawi records that Muslim scholars divide angels in at least two groups: those who are self-immersed in knowledge of "the Truth" (al-Haqq), based on "they laud night and day, they never wane" (21:29), they are the "highmost" and "angels brought near" and those who are the executors of commands, based on "they do not disobey Allah in what He commanded them but they do what they are commanded" (66:6), who are the administers of the command of heaven to earth.[4]: 509

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (d. 1209) divided the angels into eight groups, which shows some resemblance to Christian angelology:[77]

- Hamalat al-'Arsh, those who carry the 'Arsh (Throne of God),[78] comparable to the Christian Seraphim.

- Muqarrabun (Cherubim), who surround the throne of God, constantly praising God (tasbīḥ)

- Archangels, such as Jibrāʾīl, Mīkhāʾīl, Isrāfīl, and ʿAzrāʾīl

- Angels of Paradise, such as Riḍwān.

- Angels of Hell, Mālik and Zabānīya

- Guardian angels, who are assigned to individuals to protect them

- The angels who record the actions of people

- Angels entrusted with the affairs of the world, like the angel of thunder.

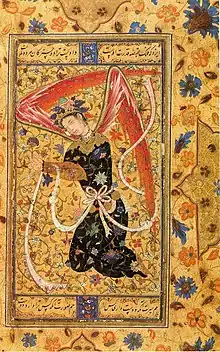

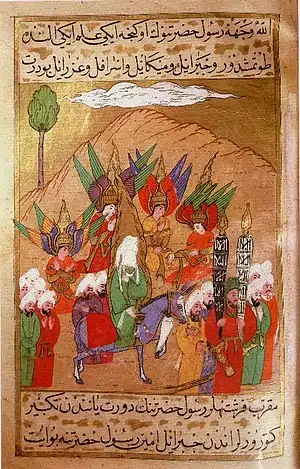

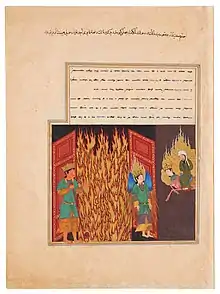

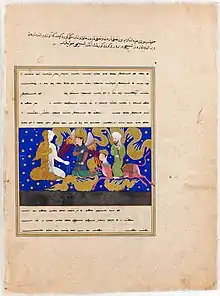

Angels in Islamic art

Angels in Islamic art often appear in illustrated manuscripts of Muhammad's life. Other common depictions of angels in Islamic art include angels with Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, angels discerning the saved from the damned on the Day of Judgement, and angels as a repeating motif in borders or textiles.[79] Islamic depictions of angels resemble winged Christian angels, although Islamic angels are typically shown with multicolored wings.[79] Angels, such as the archangel Gabriel, are typically depicted as masculine, which is consistent with God's rejection of feminine depictions of angels in several verses of Quran.[80] Nevertheless, later depictions of angels in Islamic art are more feminine and androgynous.[79]

The 13th century book Ajā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt (The Wonders of Creation) by Zakariya al-Qazwini describes Islamic angelology, and is often illustrated with many images of angels. The angels are typically depicted with bright, vivid colors, giving them unusual liveliness and other-worldly translucence.[81] While some angels are referred to as "Guardians of the Kingdom of God," others are associated with hell. An undated manuscript of The Wonders of Creation from the Bavarian State Library in Munich includes depictions of angels both alone and alongside humans and animals.[81] Angels are also illustrated in Timurid and Ottoman manuscripts, such as The Timurid Book of the Prophet Muhammad’s Ascension (Mir‘ajnama) and the Siyer-i Nebi.[82]

List of angels

Archangels (karubiyin)

There are four special angels (karubiyin)[83] considered to rank above the other angels in Islam. They have proper names, and central tasks are associated with them:

- Jibrīl/Jibrāʾīl/Jabrāʾīl (Arabic: جِبْرِيل, romanized: Jibrīl; also Arabic: جبرائيل, romanized: Jibrāʾīl or Jabrāʾīl; derived from the Hebrew גַּבְרִיאֵל, Gaḇrīʾēl)[84][85][86][87] (English: Gabriel),[88] is venerated as one of the primary archangels and as the Angel of Revelation in Islam.[84][85][86] Jibrīl is regarded as the archangel responsible for revealing the Quran to Muhammad, verse by verse;[84][85][86] he is primarily mentioned in the verses 2:97, 2:98, and 66:4 of the Quran, although the Quranic text does not explicitly refer to him as an angel.[85] Jibrīl is the angel who communicated with all of the prophets and also descended with the blessings of God during the night of Laylat al-Qadr ("The Night of Divine Destiny (Fate)"). Jibrīl is further acknowledged as a magnificent warrior in Islamic tradition, who led an army of angels into the Battle of Badr and fought against Iblis, when he tempted ʿĪsā (Jesus).[89]

- Mīkāl/Mīkāʾīl/Mīkhāʾīl (Arabic: ميكائيل)(English: Michael),[90] the archangel of mercy, is often depicted as providing nourishment for bodies and souls while also being responsible for bringing rain and thunder to Earth.[91] Some scholars have pointed out that Mikail is in charge of angels who carry the laws of nature.[92]

- Isrāfīl (Arabic: إسرافيل) (frequently associated with the Jewish and Christian angel Raphael), is the archangel who blows into the trumpet in the end time, therefore also associated with music in some traditions.[93] Israfil is responsible for signaling the coming of Qiyamah (Judgment Day) by blowing a horn. However, Ali Hasan al-Halabi (a student of Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani),[94] Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen,[95] and Al-Suyuti,[96] have given commentary that all the hadiths that describe Israfil as the horn-blower are classified as Da'if, although given the multitude of narrative chains that support this concept, they state that it is still possible.[94][96][95]

- ʿAzrāʾīl/ʿIzrāʾīl (Arabic: عزرائيل)(English: Azrael), is the archangel of death. He and his subordinative angels are responsible for parting the soul from the body of the dead and will carry the believers to heaven (Illiyin) and the unbelievers to hell (Sijjin).[97][98]

Mentioned in the Quran

- Nāziʿāt and Nāshiṭāt, helpers of Azrail who take the souls of the deceased.[99]

- Nāziʿāt: they are responsible for taking out the souls of disbelievers painfully.

- Nāshiṭāt: they are responsible for taking out the souls of believers peacefully.

- Hafaza, (the Guardian angel):

- Kiraman Katibin (Honourable Recorders),[100] two of whom are charged to every human being; one writes down good deeds and another one writes down evil deeds. They are both described as 'Raqeebun 'Ateed' in the Qur'an.

- Mu'aqqibat (the Protectors)[101] who keep people from death until its decreed time and who bring down blessings.

- Angels of Hell:

- Mālik, chief of the angels who govern Jahannam (Hell).

- Nineteen angels of hell, commanding the Zabaniyah, to torment sinful people in hell. The nineteen angel chiefs of hell were depicted in Quran chapter Al-Muddaththir verse Quran 74:10–11.[102] The Saudi Arabia religious ministry released their official interpretation that Zabaniyah were collective names of angels group which included those nineteen chief angels.[102] Those nineteen angels of hell were standing tall above Saqar, one of levels in hell.[103] Muhammad Sulaiman al-Asqar, professor from Islamic University of Madinah argued the nineteen instead were nineteen type of hell angels which each type has different kind of form.[102]

- Angels who distribute provisions, rain, and other blessings by God's command.[104]

- Ra'd or angels of thunders, a name of angels group who drive the clouds.[105][106] The angels who regulating the clouds and rains in their task given by God were mentioned in Quran 13:13 Ibn Taymiyyah in his work, Majmu al-Fatwa al-Kubra, has quoted the Marfu hadith transmitted by Ali ibn abi Thalib, that Ra'd were the name of group of angels who herded the dark clouds like a shepherd.[106][107] Ali further narrated that thunder (Ra'dan Arabic: رعدان) was the growling voices of those angels while herding the clouds, while lightning strikes (Sawa'iq Arabic: صوائق) were a flaming device used by the said angel in gathering and herding the raining clouds.[106] Al-Suyuti narrated from the hadith transmitted from Ibn Abbas about the lightning angels, while giving further commentary that hot light produced by lightning (Barq Arabic: برق) were the emitted light produced from a whip device used by those angels.[106][107] Saudi Grand Mufti Abd al-Aziz Bin Baz also ruled on the sunnah practice of reciting Sura Ar-Ra'd, Ayah 13 Quran 13:13 (Translated by Shakir) whenever a Muslim hears the sound of thunder, as this was practiced according to the hadith tradition narrated by Zubayr ibn al-Awwam.[108] The non-canonical interpretation from Salaf generation scholars regarding the tradition from Ali has described that "It is a movement of celestial clouds due to air compression in the cloud. However, this does not contradict that (the metaphysical explanation), […] the angels move the clouds from one place to another. Indeed, every movement in the upper and lower World results from the action of the angels. The voice of a person results from the movement of his body parts, which are his lips, his tongue, his teeth, his epiglottis, and his throat; he, however, along with that, is said to be praising his Lord, enjoining good, and forbidding evil."[109]

- Hamalat al-'Arsh, those who carry the 'Arsh (Throne of God),[78] comparable to the Christian Seraphim.

- Harut and Marut, a pair of fallen angels who taught humans in Babylon magic; mentioned in Quran (2:102).[110] Some scholars, such as Hasan al-Basri, don't consider Harut and Marut to be angels.[111][112]

Mentioned in canonical hadith tradition

- The angels of the Seven Heavens.

- Jundullah, those who helped Muhammad in the battlefield.[113]

- Those that give the spirit to the fetus in the womb and are charged with four commands: to write down his provision, his life-span, his actions, and whether he will be wretched or happy.[114]

- Malakul Jibaal (The Angel of the Mountains), met by the Prophet after his ordeal at Taif.[115]

- Munkar and Nakir, who question the dead in their graves.[116]

- Angel of ice an fire, an angel Muhammad met during his night journey composed of ice and fire.

- Angel who bestowed with strength equal of 70,000 angels and has 70,000 wings.[117] This angel were narrated in Al-Dur al-Manthur were able to see Al-ʽArsh, which were made of red ruby.[117]

Hadith narratives of Isra and Mi'raj

According to hadith transmitted by Ibn Abbas, Muhammad encountered several significant angels on his journey through the celestial spheres.[118][119] Many scholars such as Al-Tha'labi drew their exegesis upon this narrative, but it never led to an established angelology as known in Christianity. The principal angels of the heavens are called Malkuk, instead of Malak.[120]

The rooster angel, in Miraj Literature, was held to be "enormous" and "white", and the comb on the top of his head "graze[d] the foot of Allah's celestial throne, its feet reach[ed] the earth", and its wings were thought to be large enough to "envelop both heaven and earth" and were covered with emeralds and pearls.[121] It is also thought to wake up mankind every morning through means like making "cocks below on Earth...crow" when it opens its mouth.[122]

| First heaven | Second heaven | Third heaven | Fourth heaven | Fifth heaven | Sixth heaven | Seventh heaven |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habib | Angel of Death | Maalik | Salsa'il | Kalqa'il | Mikha'il (Archangel) | Israfil |

| Rooster angel | Angels of death | Angel with seventy heads | Angels of the sun | - | Cherubim | Bearers of the Throne |

| Ismail (or Riḍwan) | Mika'il | Arina'il | - | - | Shamka'il | Afra'il |

Mentioned in non canonical tradition

- Ridwan, the keeper of Paradise.

- Artiya'il, the angel who removes grief and depression from the children of Adam.[5]

- The angels charged with each existent thing, maintaining order and warding off corruption. Their exact number is known only to God.[lower-alpha 3][124]

- Darda'il (The Journeyers), who travel the earth searching out assemblies where people remember God's name.[125]

Disputed

- Dhul-Qarnayn, believed by some to be an angel or "part-angel" based on the statement of Umar bin Khattab.[126]

- Khidr, sometimes regarded as an angel which took human form and thus able to reveal hidden knowledge exceeding those of the prophets to guide and help people or prophets.[127]

- Azazil, considered the name of Satan before his fall by those who agree that he was an angel once.

See also

Notes

- "Differences between nūr and nar have been debated in Islam. In Arabic, both terms are closely related morphologically and phonetically.[20] Baydawi explains that the term light serves only as a proverb, but fire and light refers actually to the same substance.[21] Apart from light, other traditions also mention exceptions about angels created from fire, ice or water.[22] Tabari argued that both can be seen as the same substance, since both pass into each other but refer to the same thing on different degrees.[23] Asserting that both fire and light are actually the same but on different degrees can also be found by Qazwini and Ibishi.[24][25] In his work Al-Hay'a as-samya fi l-hay'a as-sunmya, Suyuti asserts that the angels are created from "fire that eats, but does not drink".[26]Abd al-Ghani al-Maqdisi argued that only the angels of mercy are created from light, but angels of punishment have been created from fire.[27]

- Here jinn refers to unseen creatures in general[64]

- According to Muhammad al-Bukhari, when Muhammad journeyed through the celestial spheres and met Ibrahim in Bait al-Makmur, there are 70,000 angels in that place.[123] (not a total number of angels)

References

- Webb, Gisela (2006). "Angel". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. I. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQCOM_00010. ISBN 90-04-14743-8.

- Reynolds, Gabriel S. (2009). "Angels". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett K. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Vol. 3. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23204. ISBN 978-90-04-18130-4. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Kassim, Husain (2007). Beentjes, Pancratius C.; Liesen, Jan (eds.). "Nothing can be Known or Done without the Involvement of Angels: Angels and Angelology in Islam and Islamic Literature". Deuterocanonical and Cognate Literature Yearbook. Berlin: De Gruyter. 2007 (2007): 645–662. doi:10.1515/9783110192957.6.645. ISSN 1614-337X. S2CID 201096692.

- translator: Gibril Fouad Haddad, author: ʿAbd Allah ibn ʿUmar al-Baydawi, date= 2016, title= The Lights Of Revelation And The Secrets Of Interpretation, ISBN 978-0-992-63347-8 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: checksum

- Burge, Stephen (2015) [2012]. "Part 1: Angels, Islam, and al-Suyūṭī's Al-Ḥabāʾik fī akhbār al-malāʾik – Angels in Classical Islam and contemporary scholarship". Angels in Islam: Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī's Al-Ḥabāʾik fī akhbār al-malāʾik (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 3–15. doi:10.4324/9780203144978. ISBN 9780203144978. LCCN 2011027021. OCLC 933442177. S2CID 169825282.

- Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 22-23

- "BBC – Religions – Islam: Basic articles of faith". Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- el-Zein, Amira (2009). "Correspondences Between Jinn and Humans". Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780815650706. JSTOR j.ctt1j5d836.5. LCCN 2009026745. OCLC 785782984.

- Kiel, Micah D. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 1, 2009, pp. 215–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43726529. Accessed 21 Feb. 2023.

- https://sorularlaislamiyet.com/kaynak/meleklere-iman#_Toc201395583

- Guessoum (2010-10-30). Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. ISBN 978-0-85773-075-6.

- Ali, Syed Anwer. [1984] 2010. Qurʼan, the Fundamental Law of Human Life: Surat ul-Faateha to Surat-ul-Baqarah (sections 1–21). Syed Publications. p. 121.

- Burge, Stephan R. (2011). "The Angels in Sūrat al-Malāʾika: Exegeses of Q. 35:1". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 10 (1): 50–70. doi:10.3366/E1465359109000230.

- Kuehn, Sara, Stefan Leder, and Hans-Peter Pökel. The intermediate worlds of angels: islamic representations of celestial beings in transcultural contexts. Orient-Institut, 2019. p. 336

- Welch, A.T., Paret, R. and Pearson, J.D., "al-Ḳurʾān", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 05 May 2022 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0543> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007 section 2

- Glassé, Cyril; Smith, Huston (2003). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowland Altamira. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-759-10190-6.

- Burge, Stephen (2015). Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0.

- Kuehn, Sara. "The Primordial Cycle Revisited: Adam, Eve, and the Celestial Beings." The intermediate worlds of angels (2019): 173-199.

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān Volume 3 Georgetown University, Washington DC p. 45

- Mustafa Öztürk Journal of Islamic Research Vol 2 No 2 December 200

- Houtsma, M. Th. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Band 5. Brill. p. 191. ISBN 978-9-004-09791-9 p. 191

- Fr. Edmund Teuma, O.F.M. Conv The Nature of "Ibli'h in the Qur'an as Interpreted by the Commentators p. 16

- Gauvain, Richard (2013). Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0710313560 p. 302

- Syrinx von Hees Enzyklopädie als Spiegel des Weltbildes: Qazwīnīs Wunder der Schöpfung: eine Naturkunde des 13. Jahrhunderts Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2002 ISBN 978-3-447-04511-7 page 270

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2013). Islamic Life and Thought. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-134-53818-8.

- ANTON M. HEINEN ISLAMIC COSMOLOGY A STUDY OF AS-SUYUTI'S al-Hay'a as-samya fi l-hay'a as-sunmya with critical edition, translation, and commentary ANTON M. HEINEN BEIRUT 1982 p. 143

- Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1995). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM. Brill. p. 94. ISBN 9789004098343

- Ammi Nur Baits. "How Many Angels are?". konsultasisyariah.com (in Arabic and Indonesian). yufid.org. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

(HR. Ahmad 21516, Turmudzi 2312, Abdurrazaq in Mushanaf 17934. This hadith is rated as hasan lighairihi by Shuaib Al-Arnauth).

- vol 6 تحفة الأحوذي بشرح جامع الترمذي [Tafseed Al - Ahwadi Explaining Jami at-Tirmidhi vol 6] (Hadith -- Criticism, interpretation, etc) (in Arabic). Maktabah al-Ashrafiyah. 1990. p. 695. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

Interpretation of tirmidhi Hadith: إِنِّي أَرَى مَا لَا تَرَوْنَ، وَأَسْمَعُ مَا لَا تَسْمَعُونَ أَطَّتِ السَّمَاءُ، وَحُقَّ لَهَا أَنْ تَئِطَّ مَا فِيهَا مَوْضِعُ أَرْبَعِ أَصَابِعَ إِلَّا وَمَلَكٌ وَاضِعٌ جَبْهَتَهُ سَاجِدًا لِلَّهِ، وَاللَّهِ لَوْ تَعْلَمُونَ مَا أَعْلَمُ لَضَحِكْتُمْ قَلِيلًا وَلَبَكَيْتُمْ كَثِيرًا

- Houtsma, M. Th. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Band 5. BRILL. p. 191. ISBN 978-9-004-09791-9.

- Omar Hamdan Studien Zur Kanonisierung des Korantextes: al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrīs Beiträge Zur Geschichte des Korans Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2006 ISBN 978-3-447-05349-5 page 293 (German)

- Ulrich Rudolph Al-Māturīdī und Die Sunnitische Theologie in Samarkand BRILL, 1997 ISBN 9789004100237 pp. 54-56

- Patricia Crone. The Book of Watchers in the Qurån, page 11

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said, "Angels", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 16 October 2019 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23204 Erste Online-Erscheinung: 2009 Erste Druckedition: 9789004181304, 2009, 2009-3

- Gallorini, Louise. THE SYMBOLIC FUNCTION OF ANGELS IN THE QURʾĀN AND SUFI LITERATURE. Diss. 2021.

- Mohamed Haj Yousef The Single Monad Model of the Cosmos: Ibn Arabi's Concept of Time and Creation ibnalarabi 2014 ISBN 978-1-499-77984-4 page 292

- Gallorini, Louise. THE SYMBOLIC FUNCTION OF ANGELS IN THE QURʾĀN AND SUFI LITERATURE. Diss. 2021. p. 304

- Abdullaah Al-Faqeeh (2003). "Saying 'Peace be upon him' to Angel Gabriel". Islamweb.net. Fatwa center of Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Yemen, and Mauritania Islamic educational institues. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Welch, Alford T. (2008) Studies in Qur'an and Tafsir. Riga, Latvia: Scholars Press. p. 756.

- Masood Ali Khan, Shaikh Azhar Iqbal Encyclopaedia of Islam: Religious doctrine of Islam Commonwealth, 2005 ISBN 978-8131100523 p. 153

- Yüksek Lisans Tezi Imam Maturidi'nin Te'vilatu'l-kur'an'da gaybi konulara İstanbul-2020 2501171277

- MacDonald, D.B. and Madelung, W., "Malāʾika", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 12 October 2021 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0642 First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 9789004161214, 1960-2007

- Omar Hamdan Studien zur Kanonisierung des Korantextes: al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrīs Beiträge zur Geschichte des Korans Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2006 ISBN 978-3447053495 pp. 291–292 (German)

- Street, Tony. "Medieval Islamic doctrine on the angels: the writings of Fakhr al-Dīh al-Rāzī." Parergon 9.2 (1991): 111-127.

- Austin P. Evans A commentary on the Creed of Islam Translated by Earl Edgar Elder Columbia University Press, New York 1980 ISBN 0-8369-9259-8 p. 135

- Gauvain, Richard (2013). Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God. Abingdon, England, the U.K.: Routledge. pp. 69–74. ISBN 978-0-7103-1356-0.

- Burge, Stephen R. (January 2010). "Impurity / Danger!". Islamic Law and Society. Leiden: Brill Publishers. 17 (3–4): 320–349. doi:10.1163/156851910X489869. ISSN 0928-9380. JSTOR 23034917.

- Sa'diyya Shaikh Sufi Narratives of Intimacy: Ibn Arabi, Gender, and Sexuality Univ of North Carolina Press 2012 ISBN 978-0-807-83533-3 page 114

- Christian Krokus The Theology of Louis Massignon CUA Press 2017 ISBN 978-0-813-22946-1 page 89

- islam, dinimiz. "Melekler akıllı varlıklardır – Dinimiz İslam". dinimizislam.com. (Turkish)

- https://sorularlarisale.com/melekler-gunahsiz-degil-mi-onlarda-kotu-haslet-ve-hasiyetler-olur-mu-imtihana-tabi-tutulurlar-mi-hz-adem-seytani-orada (Turkish)

- Gimaret, Daniel. "The Psalms of Islam. Al-ṣahīfat al-kāmilat al-sajjādiyya, Imam Zayn al-‛ Abidin‛ Alī ibn al-Ḥusayn, translated with an Introduction and Annotation by William C. Chittick. The Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (London, 1988; distributed by Oxford University Press)." Bulletin critique des Annales islamologiques 7.1 (1991): 59-61.

- Zohreh Abdei "Alle Wesen bestehen aus Licht" Engel in der persischen Philosophie und bei Suhrawardi Tectum Band 23 ISBN 978-3-8288-4104-8 p. 48

- Zohreh Abdei "Alle Wesen bestehen aus Licht" Engel in der persischen Philosophie und bei Suhrawardi Tectum Band 23 ISBN 978-3-8288-4104-8 p. 50

- Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines SUNY Press, 1 January 1993 ISBN 9780791415153 p. 236

- Syrinx von Hees Enzyklopädie als Spiegel des Weltbildes: Qazwīnīs Wunder der Schöpfung: eine Naturkunde des 13. Jahrhunderts Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2002 ISBN 978-3-447-04511-7 page 268 (German)

- Bowker. World Religions. p. 165.

- "Jinns or spirits in the Futuhat al-Makkiyya | Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society".

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said, "Angels", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 17 August 2021 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23204> First published online: 2009 First print edition: 9789004181304, 2009, 2009-3

- Awn, Peter J. (1983). Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology. Leiden, Germany: Brill Publishers. p. 182 ISBN 978-9004069060

- Ayman Shihadeh Sufism and Theology Edinburgh University Press, 21 November 2007 ISBN 9780748631346 pp. 54-56

- Zh. D. Dadebayev, M.T. Kozhakanova, I.K.Azimbayeva Human's Anthropological Appearance in Abai Kunanbayev's Works World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology Vol:6 2012-06-23 p. 1065

- Teuma, E. (1984). More on Qur'anic jinn. Melita Theologica, 35(1-2), 37-45.

- John Renard Historical Dictionary of Sufism Rowman & Littlefield, 19 November 2015 ISBN 9780810879744 p. 38

- Michael Anthony Sells Early Islamic Mysticism (CWS) Paulist Press 1996 ISBN 978-0-809-13619-3 page 39

- Noel Cobb Archetypal Imagination: Glimpses of the Gods in Life and Art SteinerBooks ISBN 978-0-940-26247-8 page 194

- Wright, Zachary Valentine. "Realizing Islam, Sustainable History Monograph Pilot OA."

- Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 50

- Truglia, Craig. "AL-GHAZALI AND GIOVANNI PICO DELLA MIRANDOLA ON THE QUESTION OF HUMAN FREEDOM AND THE CHAIN OF BEING." Philosophy East and West, vol. 60, no. 2, 2010, pp. 143–166. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40666556. Accessed 17 Aug. 2021.

- Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-815-65070-6 page 43

- Khaled El-Rouayheb, Sabine Schmidtke The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Philosophy Oxford University Press 2016 ISBN 978-0-199-91739-6 page 186

- Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi Akhbar al-malik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 p. 13-14

- Wensinck, A. J. (2013). The Muslim Creed: Its Genesis and Historical Development. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 200

- Imam Abu Hanifa’s Al Fiqh Al Akbar Explained By أبو حنيفة النعمان بن ثابت Abu ’l Muntaha Ahmad Al Maghnisawi Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf"

- Serdar, Murat. "Hıristiyanlık ve İslâm’da Meleklerin Varlık ve Kısımları." Bilimname 2009.2 (2009). p. 156

- Serdar, Murat. "Hıristiyanlık ve İslâm’da Meleklerin Varlık ve Kısımları." Bilimname 2009.2 (2009).

- Quran 40:7

- Blair, Sheila (1991). Images of Paradise in Islamic Art. Dartmouth College: Hood Museum of Art. p. 36.

- Ali, Mualana Muhammad. The Holy Qur'an. pp. 149–150.

- "The Wonders of Creation". www.wdl.org. 1750. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Gruber, Christiane J. (2008). The Timurid "Book of Ascension" (Micrajnama): A Study of the Text and Image in a Pan-Asian Context. Patrimonia. p. 254

- Gaudefroy-Demombynes, M. (2013). Muslim Institutions. Vereinigtes Königreich: Taylor & Francis. p. 49

- Webb, Gisela (2006). "Gabriel". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. II. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQCOM_00071. ISBN 978-90-04-14743-0.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2014). "Gabriel". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett K. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Vol. 3. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27359. ISBN 978-90-04-26962-0. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Pedersen, Jan (1965). "D̲j̲abrāʾīl". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_1903. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- Luxenberg, Christoph. 2007. The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran. Verlag Hans Schiler. ISBN 9783899300888 p. 39

- Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi Akhbar al-malik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0 chapter 3

- Islam Issa Milton in the Arab-Muslim World Taylor & Francis 2016 ISBN 978-1-317-09592-7 page 111

- Quran 2:98

- Matthew L.N. Wilkinson A Fresh Look at Islam in a Multi-Faith World: A Philosophy for Success Through Education Routledge 2014 ISBN 978-1-317-59598-4 page 106

- Syrinx von Hees Enzyklopädie als Spiegel des Weltbildes: Qazwīnīs Wunder der Schöpfung: eine Naturkunde des 13. Jahrhunderts Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2002 ISBN 978-3-447-04511-7 page 320 (German)

- Sophy Burnham A Book of Angels: Reflections on Angels Past and Present, and True Stories of How They Touch Our Lives Penguin 2011 ISBN 978-1-101-48647-4

- Aris Munandar (2011). "Benarkah Israfil Nama Malaikat Peniup Sangkakala?". Ustadz Aris (in Indonesian). Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen (1994). Majmūʻ fatāwá wa-rasāʼil Faḍīlat al-Shaykh Muḥammad ibn Ṣāliḥ al-ʻUthaymīn fatāwá al-ʻaqīdah · Volume 8 (Fatwas, Hanbalites, Islam -- Doctrines, Islamic law -- Interpretation and construction) (in Arabic). Dār al- Thurayyā lil-Nashr. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Mustafa bin Kamal Al-Din Al-Bakri (2013). الضياء الشمسي على الفتح القدسي شرح ورد السحر للبكري 1-2 ج2 [Solar illumination on the divine conquest] (Religion / Islam / Theology) (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah. p. 132. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

Al-Habaa-ik fii Akhbaaril Malaa'ik

- Syrinx von Hees Enzyklopädie als Spiegel des Weltbildes: Qazwīnīs Wunder der Schöpfung: eine Naturkunde des 13. Jahrhunderts Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2002 ISBN 978-3-447-04511-7 page 331 (German)

- Juan Eduardo Campo Encyclopedia of Islam Infobase Publishing, 2009 ISBN 978-1-438-12696-8 page 42

- Quran 79:1-2

- Quran 82:11

- Quran 13:10–11

- Abdul-Rahman al-Sa'di; professor Shalih bin Abdullah bin Humaid from Riyadh Tafsir center; Imad Zuhair Hafidz from Markaz Ta'dhim Qur'an Medina; Wahbah al-Zuhayli; Muhammad Sulaiman Al-Asqar from Islamic University of Madinah (2016). "Surat al-Muddathir ayat 30". Tafsirweb (in Indonesian and Arabic). Islamic University of Madinah; Ministry of Religious Affairs (Indonesia); Ministry of Islamic Affairs, Dawah and Guidance. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- Abdul-Rahman al-Sa'di; professor Shalih bin Abdullah bin Humaid from Riyadh Tafsir center; Imad Zuhair Hafidz from Markaz Ta'dhim Qur'an Medina; Wahbah al-Zuhayli (2016). "Surat al-Muddathir ayat 29". Tafsirweb (in Indonesian and Arabic). Islamic University of Madinah; Ministry of Religious Affairs (Indonesia); Ministry of Islamic Affairs, Dawah and Guidance. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- Quran 51:4

- Quran 37:2

- Abduh Tuasikal, Muhammad (2009). "Ada Apa di Balik Petir?". Rumaysho (in Indonesian). Retrieved 26 February 2022.

Al Khoroithi, Makarimil Akhlaq, Hadith Ali ibn Abi Talib; Ibn Taymiyyah, Majm al-Fatawa; al-Suyuti; Tafsir Jalalayn, Hasyiyah ash Shawi 1/31

- Stephen Burge (2012). Angels in Islam Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti's Al-Haba'ik Fi Akhbar Al-mala'ik (ebook) (Religion / Islam / General, Social Science / Regional Studies, Angels -- Islam). Taylor & Francis. p. 186. ISBN 9781136504747. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

257 Armad, al-Tirmidhc, al-Nasa'c, Ibn al-Mundhir, Ibn Abc latim, Abe 'l-Shaykh in al-'AVama, Ibn Mardawayh, Abe Nu'aym, in al-DalA'il, and al-kiya'in al-MukhtAra (Ibn 'Abbas)

- Ibn Baz, Abd al Aziz. "ما يحسن بالمسلم قوله عند نزول المطر أو سماع الرعد؟" [What is good for a Muslim to say when it rains or when he hears thunder?; Fatwa number 13/85]. BinBaz.org (in Arabic). Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Abdullaah Al-Faqeeh (2003). "Hadeeth stating that thunder is angel Fatwa No: 335923". Islamweb.net. Fatwa center of Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, Yemen, and Mauritania Islamic educational institues. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Hussein Abdul-Raof Theological Approaches to Qur'anic Exegesis: A Practical Comparative-Contrastive Analysis Routledge 2012 ISBN 978-1-136-45991-7 page 155

- Into the Realm of Smokeless Fire (Qur'ān 55:14): A Critical Translation of Al-Damīrī's Article on the Jinn from Ḥayāt Al-Ḥayawān Al-Kubrā (Jinn). UMI. 1953. p. 64. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Stephen Burge (2015). Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi Akhbar al-malik. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-136-50473-0.

- Surah Al-Anfaal Ayah #09 Where ALLAH said, (Remember) when you asked help of your Lord, and he answered you, indeed, I will reinforce you with a thousand from the Angels, following one another. This Ayah affirms the statement of Ar-Rabi bin Anas in Tafsir ibn e kathir while explaining the Tafsir of Ayah no 12 of surah Al-Anfal where he said in the Aftermath of badr, the people used to recognize whomever the Angels killed from those whom they killed, by the wound over their necks, fingers, and toes because those parts had Mark as if they were branded by fire.

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 1:6:315

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:54:454

- Jami' at-Tirmidhi In-book reference : Book 10, Hadith 107 | English translation : Vol. 2, Book 5, Hadith 1071

- Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (2021). Misteri Alam Malaikat (ebook) (in Indonesian). Pustaka Al-kautsar. p. 166. ISBN 9789795929512. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

Quoting Amir al-Sha'bi

- Hajjah Amina Adil (2012). "Ezra". Muhammad the Messenger of Islam: His life & prophecy. BookBaby. ISBN 978-1-618-42913-1.

- Colby, Frederick S (2008). Narrating Muhammad's Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn 'Abbas Ascension Discourse. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7518-8.

- Josef von Hammer-Purgstall Die Geisterlehre der Moslimen Staatsdruckerei, 1852 digit. 22. Juli 2010 p. 8 (German)

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A.; et al. (Authors) (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. p. 328. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- Vallance, Jeffrey. "#6". Hotel. Chapelle de Poulet. United Kingdom. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- Kelas 07 SMP Pendidikan Agama Islam dan Budi Pekerti Siswa 2017 (Islamic and Character Education for Grade 7 Junior High School 2017). Jakarta: Curriculum and Bookkeeping Center, Ministry of Education of Indonesia. 2017. p. 98. ISBN 978-602-282-912-6.

- The Vision of Islam by Sachiko Murata & William Chittick pg 86-87

- "Shirath (Jembatan) | www.dinul-islam.org". July 25, 2011. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011.

- Alfred Guillaume Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah

- Brannon Wheeler Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis A&C Black 2002 ISBN 978-0-826-44956-6 page 225