Black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity.[1][2] Black nationalist activism revolves around the social, political, and economic empowerment of black communities and people, especially to resist their cultural assimilation into white culture (through integration or otherwise), and maintain a distinct black identity.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

| This article is part of a series about |

| Black power |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

|

Black nationalists often promote black separatism, which posits the belief that black people should form territorially and politically separate nation-states. Without achieving this goal, some black separatists employ a "nation within a nation" approach, advocating various degrees of localized separation, which may be a response to several centuries of various forms of structural and cultural subjugation in many nation-states. Pan-African black nationalists variously advocate for continental African unity (aiming to eventually transition away from racial nationalism) or cultural unity among the African diaspora, which entails either a return to African or a sustained connection between Africa and American black nations. Rejecting black separatism, some US-based black nationalists conceive the black nation in cultural terms as part of American pluralism.[3][2]

Some black nationalists promote black supremacy, which envisions black superiority over other racial groups. Black nationalists often reject the term and comparisons with white supremacists, characterizing their movement as an anti-racist reaction to white supremacy and colorblind white liberalism as racist.[4] According to the American civil rights advocacy group the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC):

The black nationalist movement is a reaction to centuries of institutionalized white supremacy in America. Black nationalists believe the answer to white racism is to form separate institutions — or even a separate nation — for black people. Most forms of black nationalism are strongly anti-white, antisemitic and anti-LGBT. Some religious versions assert that black people are the biblical 'chosen people' of God.[5]

The movement arose within the African American community in the United States. In the early 20th century, Garveyism, which was promoted by the U.S.-based Marcus Garvey, furthered black nationalist ideas. Black nationalist ideas also proved to be an influence on the Black Islam movement, particularly on groups like the Nation of Islam, which was founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad. During the 1960s, black nationalism influenced the Black Panther Party and the broader Black Power movement.

History

Early history

Martin Delany (1812–1885), an African American abolitionist, was arguably the first proponent of black nationalism.[6][7] Delany is credited with the Pan-African slogan of "Africa for Africans."[8]

Inspired by the success of the Haitian Revolution, the origins of black and indigenous African nationalism in political thought lie in the 19th and early 20th centuries with people such as Marcus Garvey, Benjamin "Pap" Singleton, Henry McNeal Turner, Martin Delany, Henry Highland Garnet, Edward Wilmot Blyden, Paul Cuffe, and others. The repatriation of African-American slaves to Liberia or Sierra Leone was a common black nationalist theme in the 19th century. Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association of the 1910s and 1920s was the most powerful black nationalist movement to date, claiming millions of members. Garvey's movement was opposed by mainline black leaders, and crushed by government action. However, its many alumni remembered its inspiring rhetoric.[9]

According to Wilson Jeremiah Moses, black nationalism as a philosophy can be examined from three different periods, giving rise to various ideological perspectives for what we can today consider black nationalism.[10]

The first period of pre-classical black nationalism began when the first Africans were brought to the Americas as slaves through the American Revolutionary period.[11]

The second period of black nationalism began after the Revolutionary War. This period refers to the time when a sizeable number of educated Africans within the colonies (specifically within New England and Pennsylvania) had become disgusted with the social conditions that arose out of the Enlightenment's ideas. From this way of thinking came the rise of individuals within the black community who sought to create organizations that would unite black people. The intention of these organizations was to group black people together so they could voice their concerns, and help their own community advance itself. This form of thinking can be found in historical personalities such as; Prince Hall, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, James Forten, Cyrus Bustill, William Gray through their need to become founders of certain organizations such as African Masonic lodges, the Free African Society, and Church Institutions such as the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. These institutions served as early foundations to developing independent and separate organizations for their own people. The goal was to create groups to include those who so many times had been excluded from exclusively white communities and government-funded organizations.[12]

The third period of black nationalism arose during the post-Reconstruction era, particularly among various African-American clergy circles. Separated circles were already established and accepted because African-Americans had long endured the oppression of slavery and Jim Crowism in the United States since its inception. The clerical phenomenon led to the birth of a modern form of black nationalism that stressed the need to separate blacks from non-blacks and build separate communities that would promote racial pride and collectivize resources. The new ideology became the philosophy of groups like the Moorish Science Temple and the Nation of Islam. By 1930, Wallace Fard Muhammad had founded the Nation of Islam. His method to spread information about the Nation of Islam used unconventional tactics to recruit individuals in Detroit, Michigan. Later on, Elijah Muhammad would lead the Nation of Islam and become a mentor to people like Malcolm X.[13] Although the 1960s brought a period of heightened religious, cultural and political nationalism, it was black nationalism that would lead the promotion of Afrocentrism.

Prince Hall

Prince Hall was an important social leader of Boston following the Revolutionary War. He is well known for his contribution as the founder of Black Freemasonry. His life and past are unclear, but he is believed to have been a former slave freed after twenty one years of enslavement. In 1775, Hall and fifteen other black men joined a freemason lodge of British soldiers. After the departure of the soldiers, they created their own lodge, African Lodge #1, and were granted full stature in 1784. Despite their stature other white freemason lodges in America did not treat them equal and so Hall began to help other black Masonic lodges across the country to help their own cause - to progress as a community together despite any difficulties brought to them by racists. Hall was best recognized for his contribution to the black community along with his petitions (many denied) in the name of black nationalism. In 1787 he unsuccessfully petitioned to the Massachusetts legislature to send blacks back to Africa (to obtain "complete" freedom from white supremacy). In 1788, Hall was a well known contributor to the passing of the legislation of the outlawing of the slave-trade and those involved. Hall continued his efforts to help his community, and in 1796 his petition for Boston to approve funding for black schools. Hall and other Black Bostonians wanted separate schools to distance themselves from White supremacy and create well-educated Black citizens.[14] Despite the city's inability to provide a building, Hall lent his building for the school to run from. Until his death in 1807, Hall continued to work for black rights in issues of abolition, civil rights and the advancement of the community overall.[15]

Free African Society

In 1787 Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, black ministers of Pennsylvania, formed the Free African Society of Pennsylvania. The goal of this organization was to create a church that was free of restrictions of only one form of religion, and to pave the way for the creation of a house of worship exclusive to their community. They were successful in doing this when they created the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church in 1793. The community included many members who were notably abolitionist men and former slaves. Allen, following his own beliefs that worship should be out loud and outspoken, left the organization two years later. He later received an opportunity to become the pastor of the church, but rejected the offer, leaving it to Jones. The society itself was a memorable charitable organization that allowed its members to socialize and network with other business partners, in an attempt to better their community. Its activity and open doors served as a motivational growth for the city, inspiring many other black mutual aid societies in the city to pop up. Additionally the society is well known for their aid during the yellow fever epidemic in 1793.[16]

African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia

The African Church or the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was founded in 1792 for those of African descent, as a foster church for the community with the goal to be interdenominational. In the beginning of the church's establishment its masses were held in homes and local schools. One of the founders of the Free African Society was also the first Episcopal priest of African American descent, Absalom Jones. The original church house was constructed at 5th and Adelphi Streets in Philadelphia, now St. James Place, and it was dedicated on July 17, 1794; other locations of the church included: 12th Street near Walnut, 57th and Pearl Streets, 52nd and Parrish Streets, and the current location, Overbrook and Lancaster Avenue in Philadelphia's historic Overbrook Farms neighborhood. The church is mostly African-American. The church and its members have played a key role in the abolition/anti-slavery and equal rights movement of the 1800s.[17]

"Since 1960 St. Thomas has been involved in the local and national civil rights movement through its work with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Union of Black Episcopalians, the Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC), Philadelphia Interfaith Action, and The Episcopal Church Women. Most importantly, it has been in the forefront of the movement to uphold the knowledge and value of the black presence in the Episcopal Church. Today, that tradition continues with a still-growing membership through a host of ministries such as Christian Formation, the Chancel Choir, Gospel Choir, Jazz Ensemble, Men's Fellowship, Young Adult and Youth Ministries, a Church School, Health Ministry, Caring Ministry, and a Shepherding Program."[15]

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey encouraged African people around the world to be proud of their race and see beauty in their own kind. This form of black nationalism later became known as Garveyism. A central idea to Garveyism was that African people in every part of the world were one people and they would never advance if they did not put aside their cultural and ethnic differences and unite under their own shared history. He was heavily influenced by the earlier works of Booker T. Washington, Martin Delany, and Henry McNeal Turner.[18] Garvey used his own personal magnetism and the understanding of black psychology and the psychology of confrontation to create a movement that challenged bourgeois blacks for the minds and souls of African Americans. Marcus Garvey's return to America had to do with his desire to meet with the man who inspired him most, Booker T. Washington, however Garvey did not return in time to meet Washington. Despite this, Garvey moved forward with his efforts and two years later, a year after Washington's death, Garvey established a similar organization in America known as the United Negro Improvement Association otherwise known as the UNIA.[19] Garvey's beliefs are articulated in The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey as well as Message To The People: The Course of African Philosophy.

Nation of Islam

Wallace D. Fard founded the Nation of Islam in the 1930s. Fard took as his student Elijah (Poole) Muhammad, who later became the leader of the organization. The basis of the group was the belief that Christianity was exclusively a white man's religion forced on black people during slavery, preaching that Islam is the original religion of black people. Deviating from mainstream Islam, Elijah Muhammad taught that Fard was a Messiah and that he himself was sent by God to prepare black people for global supremacy and destruction of "the white devil".[20] The Nation of Islam promoted economic self-sufficiency for black people, seeking to establish a separate black nation in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.[21]

The members of the Nation of Islam are known as Black Muslims. As the group became more and more prominent with public figures such as Malcolm X as its orators, it received increasing attention from outsiders. In 1959 the group was the subject of a documentary named The Hate that Hate Produced, drawing negative media attention. When Elijah Muhammad died, his son Warith succeeded him as the organization's leader. Influenced by Malcolm X's departure, he converted the Nation of Islam to orthodox Sunni Islam, renaming the organization as the World Community of al-Islam in the West and later the American Muslim Mission, eventually abandoning black nationalism and the Fard's cult of personality. In 1985, Mohammed formally resigned and dissolved the American Muslim Mission, leading his followers into mainstream Muslim organizations. Several former members of the Nation of Islam, including Silias Muhammad and Elijah Muhammad's brother John Muhammad, rejected the conversion to orthodoxy, forming two new organizations that retained the Nation of Islam's original name and teachings of Elijah Muhammad.[21][22]

Succeeding Malcolm X as leader of the New York Temple, Louis Farrakhan became the Nation of Islam's most prominent spokesperson, founding a third Nation of Islam in 1978. Beginning his organization with thousands of adherents, Farrakhan re-established its national prominence, eventually purchasing Elijah Muhammad's former mosque in Chicago to refurbish it as the organization's headquarters. Farrakhan expanded the organization internationally, opening chapters in England, France, Ghana, and the Caribbean islands, cultivating relations with foreign Muslim countries, and establishing a relationship with Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. He bolstered his prominence by supporting Jesse Jackson's 1988 US presidential campaign, sponsoring the Million Man March in 1995, and promoting social reform in African-American communities. After a near-death experience in 2000, Farrakhan sought to strengthen relationships with other US racial minority groups and Warith Muhammed, eventually reducing his role within the Nation of Islam and embracing Dianetics, a practice of Scientology.[21][22]

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) classifies the Nation of Islam as a hate group, stating: "Its theology of innate black superiority over whites and the deeply racist, antisemitic and anti-LGBT rhetoric of its leaders have earned the NOI a prominent position in the ranks of organized hate."[23]

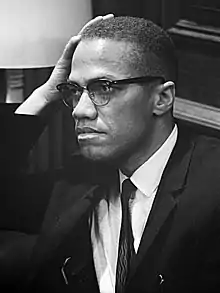

Malcolm X

Between 1953 and 1964, while most African leaders worked in the civil rights movement to integrate African-American people into mainstream American life, Malcolm X was an avid advocate of black independence and the reclaiming of black pride and masculinity.[24] He maintained that there was hypocrisy in the purported values of Western culture – from its Judeo-Christian religious traditions to American political and economic institutions – and its inherently racist actions. He maintained that separatism and control of politics, and economics within its own community would serve blacks better than the tactics of civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and mainstream civil rights groups such as the SCLC, SNCC, NAACP, and CORE. Malcolm X declared that nonviolence was the "philosophy of the fool",[25] and that to achieve anything, African Americans would have to reclaim their national identity, embrace the rights covered by the Second Amendment, and defend themselves from white hegemony and extrajudicial violence. In response to Rev. King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech, Malcolm X quipped, "While King was having a dream, the rest of us Negroes are having a nightmare."[26]

Prior to his pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm X believed that African Americans must develop their own society and ethical values, including the self-help, community-based enterprises, that the black Muslims supported. He also thought that African Americans should reject integration or cooperation with whites until they could achieve internal cooperation and unity. He prophetically believed that there "would be bloodshed" if the racism problem in America remained ignored, and he renounced "compromise" with whites. In April 1964, Malcolm X participated in a Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca); Malcolm found himself restructuring his views and recanted several extremist opinions during his shift to mainstream Islam.[27]

Malcolm X returned from Mecca with moderate views that included an abandonment of his commitment to racial separatism. However, he still supported black nationalism and advocated that African Americans in the United States act proactively in their campaign for equal human rights, instead of relying on Caucasian citizens to change the laws that govern society. The tenets of Malcolm X's new philosophy are articulated in the charter of his Organization of Afro-American Unity (a secular Pan-Africanist group patterned after the Organization of African Unity), and he inspired some aspects of the future Black Panther movement.[28]

In 1965, Malcolm X expressed reservations about black nationalism, saying, "I was alienating people who were true revolutionaries dedicated to overturning the system of exploitation that exists on this earth by any means necessary. So I had to do a lot of thinking and reappraising of my definition of black nationalism. Can we sum up the solution to the problems confronting our people as black nationalism? And if you notice, I haven't been using the expression for several months."[29]

Stokely Carmichael

In the 1967 Black Power, Stokely Carmichael introduces black nationalism. He illustrates the prosperity of the black race in the United States as being dependent on the implementation of black sovereignty. Under his theory, black nationalism in the United States would allow Blacks to socially, economically and politically be empowered in a manner that has never been plausible in American history. A Black nation would work to reverse the exploitation of the Black race in America, as Blacks would intrinsically work to benefit their own state of affairs. African Americans would function in an environment of running their own businesses, banks, government, media, and so on. Black nationalism is the opposite of integration, and Carmichael contended integration is harmful to the black population. As blacks integrate to white communities they are perpetuating a system in which blacks are inferior to whites. Blacks would continue to function in an environment of being second class citizens, he believes, never reaching equity to white citizens. Carmichael therefore uses the concept of black nationalism to promote an equality that would begin to dismantle institutional racism.

Frantz Fanon

While in France, Frantz Fanon wrote his first book, Black Skin, White Masks, an analysis of the impact of colonial subjugation on the African psyche. This book was a very personal account of Fanon's experience being black: as a man, an intellectual, and a party to a French education. Although Fanon wrote the book while still in France, most of his other work was written while in North Africa (in particular Algeria). It was during this time that he produced The Wretched of the Earth where Fanon analyzes the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for decolonization. In this work, Fanon expounded his views on the liberating role of violence for the colonized, as well as the general necessity of violence in the anti-colonial struggle. Both books established Fanon in the eyes of much of the Third World as one of the leading anti-colonial thinkers of the 20th century. In 1959 he compiled his essays on Algeria in a book called L'An Cinq: De la Révolution Algérienne.[30]

21st century

According to the SPLC, black nationalist groups face a "categorically different" environment than white hate groups in the United States; while white supremacy has been championed by influential figures within the Donald Trump administration, black nationalists have "little or no impact on mainstream politics and no defenders in high office".[5]

Patrisse Cullors, a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, has called for racial reparations in the form of "financial restitution, land redistribution, political self-determination, culturally relevant education programs, language recuperation, and the right to return (or repatriation)" and cited Frantz Fanon's work for "understanding the current global context for Black individuals on the African continent and in our multiple diasporas."[31]

The Not Fucking Around Coalition (NFAC) is a black nationalist organization in the United States. The group advocates for black liberation and separatism. It has been described by news outlets as a "Black militia".[32][33] The NFAC gained prominence during the 2020–2021 United States racial unrest, making its first reported appearance at a May 12, 2020, protest near Brunswick, Georgia, over the February murder of Ahmaud Arbery,[34] though they were identified by local media as "Black Panthers".[35] Thomas Mockaitis, professor of history at DePaul University noted that "In one sense it (NFAC) echoes the Black Panthers but they are more heavily armed and more disciplined... So far, they've coordinated with police and avoided engaging with violence."[36]

John Fitzgerald Johnson, also known as Grand Master Jay and John Jay Fitzgerald Johnson, claims leadership of the group[36][37] and has stated that it is composed of "ex military shooters".[34] In 2019 Grand Master Jay told the Atlanta Black Star that the organization was formed to prevent another Greensboro Massacre.[38][39] Johnson expressed black nationalist views, putting forth the view that the United States should either hand the state of Texas over to African-Americans so that they may form an independent country, or allow African-Americans to depart the United States to another country that would provide land upon which to form an independent nation.[40][41]

In 2016, an investigation into the online activities of Micah Johnson, perpetrator of the 2016 shooting of Dallas police officers, uncovered his interest in Mauricelm-Lei Millere and Black nationalist groups.[42] The SPLC and news outlets reported that Johnson "liked" the Facebook pages of Black nationalist organizations such as the New Black Panther Party (NBPP), Nation of Islam, and Black Riders Liberation Army, three groups which are listed by the SPLC as hate groups.[43]

In 2022, Frank James, suspect of the 2022 New York City Subway attack beliefs have been linked to black nationalism.[44][45]

Revolutionary Black nationalism

Revolutionary Black nationalism is an ideology that combines cultural nationalism with scientific socialism in order to achieve Black self-determination. Proponents of the ideology argue that revolutionary Black nationalism is a movement that rejects all forms of oppression, including class based exploitation under capitalism.[46] Revolutionary Black nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and the Revolutionary Action Movement also adopted a set of anti-colonialist politics inspired by the writings of notable revolutionary theorists including Frantz Fanon, Mao Zedong, and Kwame Nkrumah.[47] In the words of Ahmad Muhammad (formerly known as Max Stanford) the national field chairman of the Revolutionary Action Movement:

We are revolutionary black nationalist[s], not based on ideas of national superiority, but striving for justice and liberation of all the oppressed peoples of the world. ... There can be no liberty as long as black people are oppressed and the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America are oppressed by Yankee imperialism and neo-colonialism. After four hundred years of oppression, we realize that slavery, racism and imperialism are all interrelated and that liberty and justice for all cannot exist peacefully with imperialism."[48]

Professor and author Harold Cruse saw revolutionary Black nationalism as a necessary and logical progression from other leftist ideologies, as he believed that non-Black leftists could not properly assess the particular material conditions of the Black community and other colonized people:

Revolutionary nationalism has not waited for Western Marxian thought to catch up with the realities of the "underdeveloped" world...The liberation of the colonies before the socialist revolution in the West is not orthodox Marxism (although it might be called Maoism or Castroism). As long as American Marxists cannot deal with the implications of revolutionary nationalism, both abroad and at home, they will continue to play the role of revolutionaries by proxy.[49]

In Africa

Some African countries encode race in their nationality and citizenship laws. Liberia and Sierra Leone afford birthright citizenship exclusively to black people. Circa 1992, Malawi required birth to a Malawian citizen "of African race" for birthright citizenship. Similarly, Mali used to attribute birthright nationality only to children with a parent "of African origin" born in the country.[50] Ghana provides the right of return for people of African descent. Ghana is the first African state to have enacted this policy, done via the Immigration Act 573 of 2000 in response to African-American immigrant lobbying.[51] Some private Afrocentric travel and genetic ancestry tracing companies have collaborated with the governments of Ghana and Sierra Leone to promote African diasporic toursim and immigration there.[52][53]

Robert Mugabe, former President and Prime Minister of Zimbabwe, encouraged the violent seizure of white-owned farmland, commenting that "[t]he white man is not indigenous to Africa. Africa is for Africans, Zimbabwe is for Zimbabweans".[54]

Criticism

In his Letter from Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King Jr. characterized black nationalism with "hatred and despair", writing that support for black nationalism "would inevitably lead to a frightening racial nightmare."[55]

Norm R. Allen Jr., former director of African Americans for Humanism, calls black nationalism a "strange mixture of profound thought and patent nonsense":

On the one hand, Reactionary Black Nationalists (RBNs) advocate self-love, self-respect, self-acceptance, self-help, pride, unity, and so forth—much like the right-wingers who promote 'traditional family values.' But—also like the holier-than-thou right-wingers—RBNs promote bigotry, intolerance, hatred, sexism, homophobia, anti-Semitism, pseudo-science, irrationality, dogmatic historical revisionism, violence, and so forth.[56]

Tunde Adeleke, Nigerian-born professor of History and Director of the African American Studies program at the University of Montana, argues in his book UnAfrican Americans: Nineteenth-Century Black Nationalists and the Civilizing Mission that 19th-century African-American nationalism embodied the racist and paternalistic values of Euro-American culture and that black nationalist plans were not designed for the immediate benefit of Africans but to enhance their own fortunes.[57]

Black feminists in the U.S., such as Barbara Smith, Toni Cade Bambara, and Frances Beal, have also lodged sustained criticism of certain strands of black nationalism, particularly the political programs advocated by cultural nationalists. Black cultural nationalists envisioned black women only in the traditional heteronormative role of the idealized wife-mother figure. Patricia Hill Collins criticizes the limited imagining of black women in cultural nationalist projects, writing that black women "assumed a particular place in Black cultural nationalist efforts to reconstruct authentic Black culture, reconstitute Black identity, foster racial solidarity, and institute an ethic of service to the Black community."[58] A major example of black women as only the heterosexual wife and mother can be found in the philosophy and practice called Kawaida exercised by the Us Organization. Maulana Karenga established the political philosophy of Kawaida in 1965. Its doctrine prescribed distinct roles between black men and women. Specifically, the role of the black woman as "African Woman" was to "inspire her man, educate her children, and participate in social development."[59] Historian of black women's history and radical politics Ashley Farmer records a more comprehensive history of black women's resistance to sexism and patriarchy within black nationalist organizations, leading many Black Power era associations to support gender equality.[60]

Black nationalism and antisemitism

Scholars have studied the link between black nationalism and antisemitism.[61][62][63] In the late 1950s, both Muslim and non-Muslim black nationalists often embraced antisemitism.[61] Many of them taught that American Jews, as well as Israel, were "the central obstacle to black progress",[61] and that Jews were "the most racist whites".[62] During the late 1960s, black nationalists depicted Jews as "parasitic intruders who accumulated wealth by exploiting the toil of black people in America's ghettos and South Africa".[62]

According to polls, a significantly greater number of African-Americans endorsed antisemitic tropes and that the animus was "strongest among younger, better-educated... blacks".[64] A study conducted in 1970 ranked 73% of Blacks in their twenties, as opposed to 35% who were fifty and older, as high on its index of antisemitism. By 1978 a survey of "black leaders" found that 81% agreed that "Jews chose money over people".[64] In 2005, 36% of African Americans held "strong antisemitic beliefs"—four times the percentage of White Americans.[64] In 2020, 42% of "black liberals" versus 15% of "white liberals" endorsed antisemitic stereotypes.[64]

Some black nationalists deny accusations of antisemitism by alleging that black people "are the original Semites" and, as such, cannot be antisemitic.[65] Many black nationalists engage in Holocaust trivialization,[62] while some are even Holocaust deniers.[66][63] Notable black nationalist leaders who profess antisemitic sentiments include Amiri Baraka, Louis Farrakhan, Kwame Ture, Leonard Jeffries and Tamika Mallory among others.[67]

See also

- African-American culture

- African-American history

- African-American Muslims

- African diaspora

- African nationalism

- Afrocentrism

- Back-to-Africa movement

- Basking in reflected glory

- Black genocide – the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide

- Black Hebrew Israelites

- Black is beautiful

- Black Lives Matter

- Black power

- Black power movement

- Black separatism

- Black supremacy

- Hoteps

- Korean ethnic nationalism

- Pan-Africanism

- Political hip hop § Black nationalism

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Religion of black Americans

- Secession in the United States

- Tulsa race massacre

References

- "black nationalism | United States history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Hall, Raymond L. (2014). Black separatism and social reality: rhetoric and reason. New York: Pergamon Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-4831-1917-5.

- "black nationalism | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Felber, Garret (30 August 2016). "Black Nationalism and Liberation". Boston Review. Boston, Massachusetts: MIT Press. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Beirich, Heidi (Spring 2019). "The Year in Hate and Extremism: Rage Against Change" (PDF). Intelligence Report. No. 166. Montgomery, Ala.: Southern Poverty Law Center. pp. 39, 49. OCLC 796223066. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- "Martin Delany Home Page". Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009. Profile] Libraries.wvu.edu; accessed August 29, 2015.

- Stanford, E. Martin R. Delany (1812–1885). (2014, August 6). Encyclopedia Virginia Archived 20 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine - Butler, Gerry (3 March 2007). "Martin Robison Delany (1812-1885)". BlackPast. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Carlisle, Rodney P. (2005). Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. p. 811. ISBN 978-1-4129-0409-4.

- Van Deburg, William L., ed. (1997). Modern Black Nationalism: From Marcus Garvey to Louis Farrakhan. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-8789-2.

- Moses, Wilson Jeremiah, ed. (1996). Classical Black Nationalism: From the American Revolution to Marcus Garvey. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5524-2.

- "Black Nationalism". BHA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- "Systematic Inequality". Center for American Progress. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Muhammad, Nafeesa Haniyah (16 April 2010). Perceptions and Experiences in Elijah Muhammad's Economic Program: Voices from the Pioneers (Thesis). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.830.8724. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Mills, ShaVonte’ (November 2021). "An African School for African Americans: Black Demands for Education in Antebellum Boston". History of Education Quarterly. 61 (4): 478–502. doi:10.1017/heq.2021.38. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 240357493.

- Swanson, Abigail (18 January 2007). "Prince Hall (ca. 1735-1807)". BlackPast. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Free African Society of Philadelphia (1787- ?)". The Black Past. 10 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- "African American Odyssey: Abolition, Anti-Slavery Movements, and the Rise of the Sectional Controversy (Part 1)". memory.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- Skyers, Sophia (1 January 1982). Marcus Garvey and the philosophy of black pride (Thesis). Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Watson, Elwood (1994). "Marcus Garvey's Garveyism: Message from a Forefather". Journal of Religious Thought. 51 (2): 77–94. ProQuest 222118241.

- King, Shantrice King; Eby, Leah (n.d.). "Masjid An-Nur | Brief history of African Americans and Islam". Religions in Minnesota. Carleton College. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Melton, J. Gordon (9 March 2022). "Nation of Islam". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Mamiya, Lawrence A. (7 May 2022). "Louis Farrakhan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- "Nation of Islam". Extremist Files. Montgomery, Ala.: Southern Poverty Law Center. n.d. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Harris, Robert L. (October 2013). "Malcolm X: Critical Assessments and Unanswered Questions". The Journal of African American History. 98 (4): 595–601. doi:10.5323/jafriamerhist.98.4.0595. S2CID 148587259.

- Wehner, Peter (19 January 2015). "MLK and the American Founding". Commentary. ISSN 0010-2601. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023 – via Ethics and Public Policy Center.

- Cone, James H. (1992). Martin and Malcolm and America: A Dream or a Nightmare. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-88344-824-3.

- "Biography | Malcolm X". Freedom: A History of US. New York: WNET. 2002. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Marable, Manning (2011). Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02220-5.

- Breitman, George, ed. (1990) [first published 1966]. Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements. New York: Grove Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8021-3213-0.

- Macey, David (2012). Frantz Fanon: A Biography (2nd ed.). New York: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-848-8.

- Patrisse Cullors (10 April 2019). "Abolition And Reparations: Histories of Resistance, Transformative Justice, And Accountability". Harvard Law Review. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- James, Gerry Seavo; Shugerman, Emily (25 July 2020). "Three Injured as Rival Armed Militias Converge on Louisville". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Blest, Paul. "Protests Against Police Brutality and Trump's Secret Police Are Exploding Across the U.S." www.vice.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Davis, Zuri (29 May 2020). "Black Civilians Arm Themselves To Protest Racial Violence and Protect Black-Owned Businesses". Reason.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Gough, Lyndsey (9 May 2020). "Hundreds gather to release balloons to honor Ahmaud Arbery's birthday". WTOC 11. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Chavez, Nicole; Young, Ryan; Barajas, Angela (25 October 2020). "An all-Black group is arming itself and demanding change. They are the NFAC". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Ashley, Asia (6 July 2020). "Local militia challenges White supremacy during Fourth of July march". The DeKalb Champion. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "'Send a Message': Black Militia Leader Says Membership Skyrocketed After They Began Showing Up Where White Militias Protested with Little Challenge from Police". Atlanta Black Star. 13 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- "What Is the NFAC, and Who Is Grandmaster Jay?". Complex. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- "New Black Nationalist Statement Supporting the Not Fucking Around Coalition". New Black Nationalism. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Not Fucking Around Coalition". Globalsecurity.org. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- Mahler, Jonathan; Turkewitz, Julie (8 July 2016). "Suspect in Dallas Attack Had Interest in Black Power Groups". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Beirich, Heidi; Lenz, Ryan (8 July 2016). "Dallas Sniper Connected to Black Separatist Hate Groups on Facebook". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- "The liberal establishment is erasing Black Identity Extremism". Newsweek. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Tress, Luke (13 April 2022). "Man sought by NYPD for subway shooting compared Black Americans to Holocaust Jews". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Newton, Huey P. (1968). Huey Newton Talks to The Movement about the Black Panther Party: Cultural Nationalism, SNCC, Liberals and White Revolutionaries (PDF). Students for a Democratic Society – via Archive.lib.msu.edu.

- Hilliard, David; Weise, Donald, eds. (2002). The Huey P. Newton reader. New York: Seven Stories Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-58322-466-3.

- Bloom, Joshua; Martin, Waldo E. Jr. (2013). Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press. p. 30. doi:10.1525/9780520966451. ISBN 978-0-520-27185-2. S2CID 241386803.

- Cruse, Harold (1968). Rebellion or Revolution?. New York: William Morrow & Co. p. 75. LCCN 68029609. OCLC 671289.

- Manby, Bronwen (2016). Citizenship Law in Africa (PDF) (3rd ed.). Cape Town: African Minds. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-928331-08-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2022 – via Opensocietyfoundations.org.

- Manby (2016), p. 102.

- Diakite, Parker. (2021, May 18). Sierra Leone Will Grant You Citizenship Thanks To Black-Owned Ancestry Company. Travel Noire. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://travelnoire.com/sierra-leone-citizenship-ancestry-company Archived 26 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Diakite, Parker. (2020, April 28). How Ghana's Year Of Return Campaign Put Black Destinations In The Spotlight. Travel Noire. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://travelnoire.com/ghana-year-return-campaign-black-destinations-in-the-spotlight Archived 10 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Meredith, Martin (2002). Our Votes, Our Guns: Robert Mugabe and the Tragedy of Zimbabwe (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-58648-128-5.

- King, Martin Luther Jr. (16 April 1963). "Letter from a Birmingham Jail [King, Jr.]". The Africa Center, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- Allen, Norm R. Jr. (Fall 1995). "Reactionary Black Nationalism: Authoritarianism in the Name of Freedom" (PDF). Free Inquiry. 15 (4): 10–11. ISSN 0272-0701. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023 – via Center for Inquiry.

- Adeleke, Tunde (1998). UnAfrican Americans: Nineteenth-Century Black Nationalists and the Civilizing Mission. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2056-0.

- Collins, Patricia Hill (2006). From Black Power to Hip Hop: Racism, Nationalism, and Feminism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-59213-091-7. OCLC 60596227.

- Halisi, Clyde (1967). The Quotable Karenga. Los Angeles: US Organization. p. 20. ASIN B0007DTF4C. OCLC 654980714.

- Farmer, Ashley D. (2017). Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era. UNC Press Books. doi:10.5149/northcarolina/9781469634371.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4696-3438-8.

- Pollack, Eunice G. (2010). "African Americans and the Legitimization of Antisemitism on the Campus". Anti-Semitism on the Campus. Academic Studies Press. pp. 216–233. doi:10.1515/9781618110428-011. ISBN 978-1-61811-042-8. S2CID 213707374.

- Norwood, Stephen H. (2013). Antisemitism and the American Far Left. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17, 231, 242. ISBN 978-1-107-03601-7.

- Fischel, Jack (1995). "The New Anti-Semitic Axis: Holocaust Denial, Black Nationalism, and the Crisis on our College Campuses". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 71 (2): 210–226. ISSN 0042-675X. JSTOR 26437542. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Pollack, Eunice G. (2022). "Black Antisemitism in America: Past and Present" (PDF). Institute for National Security Studies. pp. 1–2, 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Pollack, Eunice G. (2013). Racializing Antisemitism: Black Militants, Jews, and Israel 1950-present (PDF). Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Johnson, Daryl (8 August 2017). "Return of the Violent Black Nationalist". Southern Poverty Law Center. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- Maizels, Linda (30 April 2018). "Black nationalist antisemitism on campus requires Jews to be 'white'". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

Further reading

- Gavins, Raymond, ed. The Cambridge Guide to African American History (2015).

- Levy, Peter B. ed. The Civil Rights Movement in America: From Black Nationalism to the Women's Political Council (2015).

- Bush, Roderick D. We Are Not What We Seem: Black Nationalism and Class Struggle in the American (2000)

- Moses, Wilson. Classical Black Nationalism: From the American Revolution to Marcus Garvey (1996), excerpt and text search

- Ogbar, Jeffrey O.G. Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity (2019), excerpt and a text search

- Price, Melanye T. Dreaming Blackness: Black Nationalism and African American Public Opinion (2009), excerpt and a text search

- Robinson, Dean E. Black Nationalism in American Politics and Thought (2001)

- Taylor, James Lance. Black Nationalism in the United States: From Malcolm X to Barack Obama (Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2011)* ALA Award "Best of the Best"Book.

- Ture, Kwame. Black Power The Politics of Liberation (1967)