Cangjie input method

The Cangjie input method (Tsang-chieh input method, sometimes called Changjie, Cang Jie, Changjei[1] or Chongkit) is a system for entering Chinese characters into a computer using a standard computer keyboard. In filenames and elsewhere, the name Cangjie is sometimes abbreviated as cj.

| Cangjie input method | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

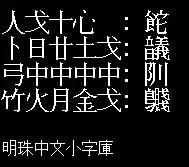

Coding of "倉頡輸入法" (i.e. Cangjie method) in traditional Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 倉頡輸入法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 仓颉输入法 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The input method was invented in 1976 by Chu Bong-Foo, and named after Cangjie (Tsang-chieh), the mythological inventor of the Chinese writing system, at the suggestion of Chiang Wei-kuo, the former Defense Minister of Taiwan. Chu Bong-Foo released the patent for Cangjie in 1982, as he thought that the method should belong to Chinese cultural heritage.[2] Therefore, Cangjie has become open-source software and is on every computer system that supports traditional Chinese characters, and it has been extended so that Cangjie is compatible with the simplified Chinese character set.

Cangjie is the first Chinese input method to use the QWERTY keyboard. Chu saw that the QWERTY keyboard had become an international standard, and therefore believed that Chinese-language input had to be based on it.[3] Other, earlier methods use large keyboards with 40 to 2400 keys, except the Four-Corner Method, which uses only number keys.

Unlike the Pinyin input method, Cangjie is based on the graphological aspect of the characters: each graphical unit, called a "radical" (not to be confused with Kangxi radicals), is re-parented by a basic character component, 24 in total, each mapped to a particular letter key on a standard QWERTY keyboard. An additional "difficult character" function is mapped to the X key. Keys are categorized into four groups, to facilitate learning and memorization. Assigning codes to Chinese characters is done by separating the constituent "radicals" of the characters.

Overview

Keys and "radicals"

The basic character components in Cangjie are called "radicals" (字根) or "letters" (字母). There are 24 radicals but 26 keys; the 24 radicals (the basic shapes 基本字形) are associated with roughly 76 auxiliary shapes (輔助字形), which in many cases are either rotated or transposed versions of components of the basic shapes. For instance, the letter A (日) can represent either itself, the slightly wider 曰, or a 90° rotation of itself. (For a more complete account of the 76-odd transpositions and rotations than the ones listed below, see the article on Cangjie entry in Chinese Wikibooks.)

The 24 keys are placed in four groups:

- Philosophical Group — corresponds to the letters 'A' to 'G' and represents the sun, the moon, and the five elements

- Strokes Group — corresponds to the letters 'H' to 'N' and represents the brief and subtle strokes

- Body-Related Group — corresponds to the letters 'O' to 'R' and represents various parts of the human anatomy

- Shapes Group — corresponds to the letters 'S' to 'Y' and represents complex and enclosed character forms

| Group | Key | Name | Primary meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophical group | A | 日 sun | 日, 曰, 90° rotated 日 (as in 巴) |

| B | 月 moon | the top four strokes of 目; 冂; 爫; 冖; the top and top-left part of 炙, 然, and 祭; the top-left four strokes of 豹 and 貓; and the top four strokes of 骨 | |

| C | 金 gold | itself, 丷, 八, and the penultimate two strokes of 四 and 匹 | |

| D | 木 wood | itself, the first two strokes of 寸 and 才, the first two strokes of 也 and 皮 | |

| E | 水 water | 氵, the last five strokes of 暴 and 康, 又 | |

| F | 火 fire | the shape 小, 灬, the first three strokes in 當 and 光 | |

| G | 土 earth | itself, or 士 for soldier | |

| Stroke group | H | 竹 bamboo

(斜 apostrophe) |

The slant and short slant, the Kangxi radical 竹, namely the upper parts in 笨 and 節 |

| I | 戈 dagger axe (點 dot) | The dot, the first three strokes in 床 and 庫, and the shape 厶 | |

| J | 十 ten (交 cruciform) | The cross shape and the shape 宀 | |

| K | 大 big (叉 cross) | The X shape, including 乂 and the first two strokes of 右, as well as 疒 | |

| L | 中 centre (緃 vertical) | The vertical stroke, as well as 衤 and the first four strokes of 書 and 盡 | |

| M | 一 one (橫 horizontal) | The horizontal stroke, as well as the final stroke of 孑 and 刁, the shape 厂, and the shape 工 | |

| N | 弓 bow (鈎 hook) | The crossbow and the hook | |

| Body parts group | O | 人 person | The dismemberment; the Kangxi radical 人; the first two strokes of 丘 and 乓; the first two strokes of 知, 攻, and 氣; and the final two strokes of 兆 |

| P | 心 heart | The Kangxi radical 忄; the second stroke in 心; the last four strokes in 恭, 慕, and 忝; the shape 匕; the shape 七; the penultimate two strokes in 代; and the shape 勹 | |

| Q | 手 hand | The Kangxi radical 手 | |

| R | 口 mouth | The Kangxi radical 口 | |

| Character shapes group | S | 尸 corpse | 匚, the first two strokes of 己, the first stroke of 司 and 刀, the third stroke of 成 and 豕, the first four strokes of 長 and 髟 |

| T | 廿 twenty | Two vertical strokes connected by a horizontal stroke; the Kangxi radical 艸 when written as 艹 (whether the horizontal stroke is connected or broken) | |

| U | 山 mountain | Three-sided enclosure with an opening on the top | |

| V | 女 woman | A hook to the right; a V shape; the last three strokes in 艮, 衣, and 長 | |

| W | 田 field | Itself, as well as any four-sided enclosure with something inside it, including the first two strokes in 母 and 毋 | |

| Y | 卜 fortune telling | The 卜 shape and rotated forms, the shape 辶, the first two strokes in 斗 | |

| Collision/Difficult key* | X | 重/難 collision/difficult | (1) disambiguation of Cangjie code decomposition collisions, (2) code for a "difficult-to-decompose" part |

| Special character key* | Z | (See note) | Auxiliary code used for entering special characters (no meaning on its own). In most cases, this key combined with other keys will produce Chinese punctuations (such as 。,、,「 」,『 』).

Note: Some variants use Z as a collision key instead of X. In those systems, Z has the name "collision" (重) and X has the name "difficult" (難); but the use of Z as a collision key is neither in the original Cangjie nor used in the current mainstream implementations. In other variants, Z may have the name "user-defined" (造) or some other name. |

| Wildcard | Shift + 8 (*) | Wildcard | It can replace any key from 2nd to 5th place, and return a list matches the combination. It is very useful for unknown guesses when you are sure about the first and last input. (e.g. Input 竹*竹 will include the following in the list: 身, 物, 秒, 第 ) |

The auxiliary shapes of each Cangjie radical have changed slightly across different versions of the Cangjie method. Thus, this is one reason that different versions of the Cangjie method are not completely compatible.

Chu Bong-Foo has provided alternate names for some letters according to their characteristics. For example, H (竹) is also called 斜, which means slant. The names form a rhyme to help learners memorize the letters, each group being in a line (The sounds of final characters are given in parentheses):

- 日 月 金 木 水 火 土; tǔ

- 斜 點 交 叉 縱 橫 鈎; gōu

- 人 心 手 口; kǒu

- 側 並 仰 紐 方 卜; bǔ

Keyboard layout

Basic rules

The typist must be familiar with several decomposition rules (拆字規則) that define how to analyze a character to arrive at a Cangjie code.

- Direction of decomposition: left to right, top to bottom, and outside to inside

- Geometrically connected forms: take four Cangjie codes, namely the first, second, third, and last codes

- Geometrically unconnected forms that can be broken into two subforms (e.g., 你): identify the two geometrically connected subforms according to the direction of decomposition rules (i.e., 人 and 尔), then take the first and last codes of the first subform and the first, second, and last code of the second subform.

- Geometrically unconnected forms that can be broken into multiple subforms (e.g., 謝): identify the first geometrically connected subform according to the direction of decomposition rules (i.e., 言) and take the first and last codes of that form. Next, break the remainder (i.e., 射) into subforms (i.e., 身 and 寸) and take the first and last codes of the first subform and the last code of the last subform.

The rules are subject to various principles:

- Conciseness (精簡) – if multiple ways of decomposition are possible, the shorter decomposition is considered to be correct.

- Completeness (完整) – if multiple ways of decomposition with the same length of code are possible, the one that identifies a more complex form first is the correct decomposition.

- Reflection of the form of the radical (字型特徵) – the decomposition should reflect the shape of the radical, meaning (a) using the same code twice or more should be avoided if possible, and (b) the shape of the character should not be "cut" at a corner in the form.

- Omission of codes (省略)

- Partial omission (部分省略) – when the number of codes in a complete decomposition exceeds the permitted number of codes, the extra codes are ignored.

- Omission in enclosed forms (包含省略) – when part of the character to be decomposed and the form is an enclosed form, only the shape of the enclosure is decomposed; the enclosed forms are omitted.

Examples

- 車; chē; 'vehicle'

- This character is geometrically connected, consisting of a single vertical structure, so we take the first, second, and last Cangjie codes from top to bottom.

- The Cangjie code is thus 十 田 十 (JWJ), corresponding to the basic shapes of the codes in this example.

- 謝}; xiè; 'to thank, to wither'

- This character consists of geometrically unconnected parts arranged horizontally. For the initial decomposition, we treat it as two parts, 言 and 射.

- The first part, 言, is geometrically unconnected from top to bottom; we take the first (亠, auxiliary shape of 卜 Y) and last parts (口, basic shape of 口 R) and arrive at 卜 口 (YR).

- The second part is again geometrically unconnected, arranged horizontally. The two parts are 身 and 寸.

- For the first part of this second part, 身, we take the first and last codes. Both are slants and therefore H; the first and last codes are thus 竹 竹 (HH).

- For the second part of the original second part, 寸, we take only the last part. Because this is geometrically unconnected and consists of two parts, the first part is the outer form while the second part is the dot in the middle. The dot is I, and therefore the last code is 戈 (I).

- The Cangjie code is thus 卜 口 (YR) 竹 竹 (HH) 戈 (I), or 卜 口 竹 竹 戈 (YRHHI).

- 谢 (simplified version of 謝)

- This example is identical to the example just above, except that the first part is 讠; the first and last codes are 戈 (I) and 女 (V).

- Repeating the same steps as in the above example, we get 戈 女 (IV) 竹 竹 (HH) 戈 (I), or 戈 女 竹 竹 戈 (IVHHI).

Exceptions

Some forms are always decomposed in the same way, whether the rules say they should be decomposed this way or not. The number of such exceptions is small:

| Form | Fixed decomposition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Version 2 | Version 3 | Version 5 | |

| 門 (door) | 日 弓 (AN) | ||

| 目 (eye) | 月 山 (BU) | ||

| 鬼 (ghost) | 竹 戈 (HI) | 竹 戈 (HI) or HUI | — |

| 几 (small table) | 竹 山 (HU) | 竹 弓 (HN) | |

| 贏 (win) | — | 卜 口 月 月 弓 (YRBBN) | 卜 弓 月 山 金 (YNBUC) |

| 虍 (tiger [radical]) | 卜 心 (YP) | ||

| 亡 on top of 口 (吂) | 卜 口 (YR) | 卜 女 口 (YVR) | |

| 隹 (fowl) | 人 土 (OG) | ||

| 气 (air [radical]) | 人 山 (OU) | 人 弓 (ON) | 人 一 弓 (OMN) |

| 畿 minus the 田 | 女 戈 (VI) | ||

| 鬥 (compete) | 中 弓 (LN) | ||

| 阝 (mound or city radical) | 弓 中 (NL) | ||

Some forms cannot be decomposed. They are represented by an X, which is the 難 key on a Cangjie keyboard.[4]

| Form | Fixed decomposition (v5) |

|---|---|

| 臼 | HX |

| 與 | HXYC |

| 興 | HXBC |

| 盥 | HXBT |

| 姊 | VLXH |

| 齊 | YX |

| 兼 | TXC |

| 鹿 | IXP |

| 身 | HXH |

| 卍 | NX |

| 黽 | RXU |

| 龜 | NXU |

| 廌 | IXF |

| 慶 | IXE |

| 淵 | ELXL |

| 肅 | LX |

Early development

Initially, the Cangjie input method was not intended to produce a character in any character set. Instead, it was part of an integrated system consisting of the Cangjie input rules and a Cangjie controller board. This controller board contains character generator firmware, which dynamically generates Chinese characters from Cangjie codes when characters are output, using the hi-res graphics mode of the Apple II computer. In the preface of the Cangjie user's manual, Chu Bong-Foo wrote in 1982:

[in translation]

In terms of output: The output and input, in fact, [form] an integrated whole; there is no reason that [they should be] dogmatically separated into two different facilities.… This is in fact necessary.…

In this early system, when the user types "yk", for example, to get the Chinese character 文, the Cangjie codes do not get converted to any character encoding and the actual string "yk" is stored. The Cangjie code for each character (a string of 1 to 5 lowercase letters plus a space) was the encoding of that particular character.

A particular "feature" of this early system is that, if one sends random lowercase words to it, the character generator will attempt to construct Chinese characters according to the Cangjie decomposition rules, sometimes causing strange, unknown characters to appear. This unintended feature, "automatic generation of characters", is described in the manual and is responsible for producing more than 10,000 of the 15,000 characters that the system can handle. The name Cangjie, evocative of the creation of new characters, was indeed apt for this early version of Cangjie.

The presence of the integrated character generator also explains the historical necessity for the existence of the "X" key, which is used for the disambiguation of decomposition collisions: because characters are "chosen" when the codes are "output", every character that can be displayed must in fact have a unique Cangjie decomposition. It would not make sense—nor would it be practical—for the system to provide a choice of candidate characters when a random text file is displayed, as the user would not know which of the candidates is correct.

Issues

Cangjie was designed to be an easy-to-use system to help promote the use of Chinese computing. However, many users find Cangjie is difficult to learn and use, with many difficulties caused by poor instruction.

Perceived difficulties

- In order to input using Cangjie, knowledge of both the names of the radicals as well as their auxiliary shapes is required. It is common to find tables of the Cangjie radicals with their auxiliary shapes taped onto the monitors of computer users.

- One must also be familiar with the decomposition rules, lack of knowledge of which results in increased difficulty in typing the intended characters.

- The user cannot type a character that they have forgotten how to write (a problem with all non-phonetic based input methods).

With enough practice, users can overcome the above problems. Typical touch-typists can type Chinese at 25 characters per minute (cpm), or better, using Cangjie, despite having difficulty remembering the list of auxiliary shapes or the decomposition rules. Experienced Cangjie typists can reportedly attain a typing speed from 60 cpm to over 200 cpm.

according to Mr. Chen Minzheng, his teaching experience at Longtian Elementary School in Taitung in 1990, the average typing speed of children was 90 words per minute, and some children even reached more than 130 words per minute.[5]

Limitations in implementation

The decomposition of a character depends on a predefined set of "standard shapes" (標準字形). However, as many variations of Cangjie exist in different countries, the standard shape of a certain character in Cangjie is not always the one the user has learnt before. Learning Cangjie then entails learning not only Cangjie itself but also unfamiliar standard shapes for some characters. The Cangjie input method editor (IME) does not handle mistakes in decomposition except by informing the user (usually by beeping) that there is a mistake. However, Cangjie is originally designed to assign different codes to different variants of a character. For example, in the Cangjie provided on Windows, the code for 產 is YHHQM, which corresponds not to the shape of this character but to another variant, 産. This is a problem resulting from the implementation of Cangjie on Windows. In the original Cangjie, 產 should be YKMHM (the first part is 文) while 産 is YHHQM (the first part is 产).

Punctuation marks are not geometrically decomposed, but rather given predefined codes that begin with ZX followed by a string of three letters related to the ordering of the characters in the Big5 code. (This set of codes was added to Cangjie on the traditional Chinese version of Windows 95. On Windows 3.1, Cangjie did not have a set of codes for punctuation marks.) Typing punctuation marks in Cangjie thus becomes a frustrating exercise involving either memorization or pick-and-peck. However, this is solved on modern systems through accessing a virtual keyboard on screen (On Windows, this is activated by pressing Ctrl + Alt + comma key).

Commonly-made errors include not considered as alternative codes. For example, if one does not decompose 方 from top to bottom into YHS, but instead type YSH according to stroke order, Cangjie does not return the character 方 as a choice.

Since Cangjie requires all 26 keys of the QWERTY keyboard, it cannot be used to input Chinese characters on feature phones, which have only a 12-key keypad. Alternative input methods, such as Zhuyin, 5-stroke (or 9-stroke by Motorola), and the Q9 input method, are used instead.

Versions

The Cangjie input method is commonly said to have gone through five generations (commonly referred to as "versions" in English), each of which is slightly incompatible with the others. Currently, version 3 (第三代倉頡) is the most common and supported natively by Microsoft Windows. Version 5 (第五代倉頡), supported by the Free Cangjie IME and previously the only Cangjie supported by SCIM, represents a significant minority method and is supported by iOS.

The early Cangjie system supported by the Zero One card on the Apple II was Version 2; Version 1 was never released.

The Cangjie input method supported on the classic Mac OS resembles both Version 3 and Version 5.

Version 5, like the original Cangjie input method, was created directly by Chu. He had hoped that the release of Version 5, originally slated to be Version 6, would bring an end to the "more than ten versions of Cangjie input method" (slightly incompatible versions created by different vendors).

Version 6 has not yet been released to the public, but is being used to create a database which can accurately store every historical Chinese text.

Variants

Most modern implementations of Cangjie input method editors (IME) provide various convenient features:

- Some IMEs list all characters beginning with the code you have typed. For example, if you type A, the system gives you all characters whose Cangjie code begins with A, so that you can select the correct character if it is on the screen; if you type another A, the list is shortened to give all characters whose code begins with AA. Examples of such implementations include the IME in Mac OS X, and the Smart Common Input Method (SCIM).

- Some IMEs provide one or more wildcard keys, usually but not always * and/or ?, that allow the user to omit part(s) of the Cangjie code; the system will display a list of matching characters for the user to choose. Examples include the X window Chinese INput XIM server (xcin), the Smart Common Input Method (SCIM), and the IME of the Founder Group (University of Peking) typesetting systems. Microsoft Windows's standard "Changjie" IME allows * to substitute for in-between characters (effectively reducing it to Simplified Cangjie entries), while the "New Changjie" IME allows * as a wildcard anywhere except for the first character.

- Some IMEs provide an "abbreviation" feature, where impossible Cangjie codes are interpreted as abbreviations for the Cangjie codes of more than one character. This allows more characters to be input with fewer keys. An example is the Smart Common Input Method (SCIM).

- Some IMEs provide an "association" (聯想 lianxiang) feature, where the system anticipates what you are going to type next, and provides you with a list of characters or even phrases associated with what the user has typed. An example is the Microsoft "Changjie" IME.

- Some IMEs present the list of candidate characters differently, depending on the frequency of character use (how often that character has been typed by the user). An example is the Cangjie IME in the NJStar Chinese word processor.

Besides the wildcard key, many of these features are convenient for casual users but unsuitable for touch-typists because they make the Cangjie IME unpredictable.

There have also been various attempts to "simplify" Cangjie one way or another:

- Simplified Cangjie, also known as quick, 簡易; jiǎnyì or 速成; sùchéng, has the same radicals, auxiliary shapes, decomposition rules, and short list of exceptions as Cangjie, but only the first and last codes are used if more than two codes are required in Cangjie.

Applications

Many researchers have discussed ways to decompose Chinese characters into their major components, and tried to build applications based on the decomposition system. The idea can be referred to as the study of the Genes of Chinese Characters. Cangjie codes offer a basis for such an endeavour. Academia Sinica in Taiwan[6] and Jiaotong University in Shanghai[7] have similar projects as well.

One direct application of the use of decomposed characters is the possibility of computing the similarities between different Chinese characters.[8] The Cangjie input method offers a good starting point for this kind of application. By relaxing the limit of five codes for each Chinese character and adopting more detailed Cangjie codes, visually similar characters can be found by computation. Integrating this with pronunciation information enables computer-assisted learning of Chinese characters.[9]

See also

- Chinese input methods for computers

- Keyboard layout

- More complete table of input shapes at Chinese Wikibooks

- OpenVanilla – a framework that provides facilities to use Cangjie on Mac OS X.

Notes

- Taipei: Chwa! Taiwan Inc. (全華科技圖書公司). 倉頡中文資訊碼 : 倉頡字母、部首、注音三用檢字對照 [The Cangjie Chinese information code : with indexes keyed by Cangjie radicals, Kangxi radicals, and zhuyin]. Publication number 023479. — This is the user manual of an early Cangjie system with a Cangjie controller card.

- The second-to-last paragraph on the first page in the section entitled "The Cangjie radical-based Chinese input method" (倉頡字母中文輸入法) states that

[Translation]

This is no problem; there are also auxiliary forms to complement the deficiencies of the radicals. The auxiliary forms are variations of the shape of the radicals, [and therefore] easy to remember. - The last paragraph on the fifth page in the same section states

[Translation]

The dictionary appended [to this book] is based on the 4800 standard, commonly used characters as proclaimed by the Ministry of Education. Adding to this the characters that are automatically generated, the number of characters is about 15,000 (using the Kangxi dictionary as a basis).

- The second-to-last paragraph on the first page in the section entitled "The Cangjie radical-based Chinese input method" (倉頡字母中文輸入法) states that

- Part of the information from this article comes from the equivalent Chinese-language Wikipedia article

- The decomposition rules come from the "Friend of Cangjie — Malaysia" web site at http://www.chinesecj.com/ The site also gives the typing speed of experienced typists and provides software for version 5 of the Cangjie method for Microsoft Windows.

- It might be difficult to find specific references to the "not error-forgiving" property of Cangjie. The table at https://web.archive.org/web/20050206223713/http://www.array.com.tw/keytool/compete.htm is one external reference that states this fact.

- Input.foruto.com has a brief history of the Cangjie input method as seen by that article's author. Versions 1 and 2 are clearly identified in the article.

- Cbflabs.com contains a number of articles written by Mr Chu Bong-Foo, with references not only to the Cangjie input method, but also Chinese language computing in general. Versions 5 and 6 (now referred to as 5) of the Cangjie input method are clearly identified.

References

- A spelling used as filename on ETen Chinese System.

- Chu, Chyi-Hwa (朱麒華) (1 February 2012). "教育科技的專利與普及". National Academy for Educational Research e-Newsletter (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- Chu Bong-foo (朱邦復). "智慧之旅". 開放文學 (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "倉頡取碼規則及方法" [Cangjie code retrieval rules and methods]. Friends of Cangjie (in Chinese). 1997–2002. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- https://www.chinesecj.com/forum/forum.php?mod=attachment&aid=MTIwNnw1MjMxNmQwMXwxNjg2OTYyNTE4fDB8MTUwMjQ%3D page 58

- "漢字構形資料庫" [Chinese Character Configuration Database]. Chinese Document Processing Lab (in Chinese). 2013. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- 上海交通大學漢字編碼組,上海漢語拼音文字研究組編著。漢字信息字典。北京市科學出版社,1988。

- 宋柔,林民,葛詩利。漢字字形計算及其在校對系統中的應用,小型微型計算機系統,第29卷第10期,第1964至1968頁,2008。

- Liu, Chao-Lin; Lai, Min-Hua; Tien, Kan-Wen; Chuang, Yi-Hsuan; Wu, Shih-Hung; Lee, Chia-Ying (2011). "Visually and phonologically similar characters in incorrect Chinese words: Analyses, identification, and applications". ACM Transactions on Asian Language Information Processing. 10 (2): 1–39. doi:10.1145/1967293.1967297. S2CID 7288710.

External links

- Online Cangjie Input Method 網上倉頡輸入法

- The Chinese University of Hong Kong Research Centre for Humanities Computing: Chinese Character Database: With Word-formations Phonologically Disambiguated According to the Cantonese Dialect: A Chinese character database covering the entire set of Big-5 Chinese characters (5401 Level 1 and 7652 Level 2 Hanzi) as well as 7 additional ETen Hanzi. Cangjie input codes are shown for each character in the database. Note: The Hong Kong Supplementary Character Set (HKSCS - 2001) is not included in this database.

- Mingzhu generator(in Chinese): Chu Bong Foo's page. Includes the executable, sourcecode and instructions. Mingzhu is a Canjie character generator that runs on MS Windows ' "DOS PROMPT". It requires Microsoft Macro Assembler and Link.

- Friend of the Cangjie: a Cangjie reference and a place where it is possible to download the Cangjie 5 for various operating systems, and Cangjie's supplementary input code lists for inputting the Simplified characters

- CjExplorer: a tool for learning Cangjie. The Cangjie code for a highlighted Chinese character will be displayed when the tool is running.

- Overview of the Cang-Jie Method: a great resource for English speakers to learn the rules and method of Cangjie.

- Online Cangjie Input Method Editor (IME) 網上倉頡輸入法

- 倉頡之友。馬來西亞