Chindesaurus

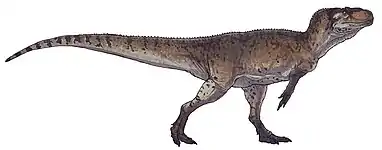

Chindesaurus (/ˌtʃɪndɪˈsɔːrəs/ CHIN-diss-OR-əs) is an extinct genus of basal saurischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic (213-210 million years ago) of the southwestern United States. It is known from a single species, C. bryansmalli, based on a partial skeleton recovered from Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. The original specimen was nicknamed "Gertie", and generated much publicity for the park upon its discovery in 1984 and airlift out of the park in 1985. Other fragmentary referred specimens have been found in Late Triassic sediments throughout Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, but these may not belong to the genus.[1] Chindesaurus was a bipedal carnivore, approximately as large as a wolf.[2]

| Chindesaurus Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of Chindesaurus bryansmalli. Known elements in white and light grey, and unknown in dark gray. Missing elements based on Tawa hallae. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Genus: | †Chindesaurus Long & Murray, 1995 |

| Species: | †C. bryansmalli |

| Binomial name | |

| †Chindesaurus bryansmalli Long & Murry, 1995 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chindesaurus's classification is debated, and various papers have had different conclusions on its affinities. Its fossils were originally believed to belong to "prosauropods" (basal sauropodomorphs), but its original description and numerous subsequent papers argued that it was a herrerasaurid[3][4][5] or herrerasaurian.[6] A 2019 redescription of its holotype considered Chindesaurus to be a theropod closely related to Tawa, a slightly smaller dinosaur known from the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico.[1]

Discovery

Holotype

Although many specimens have been referred to Chindesaurus, only one specimen has enough material to remain within the genus with certainty.[1] This specimen, holotype PEFO 10395, is a partial skeleton, found within Petrified Forest National Park in Apache County, Arizona. PEFO 10395 was discovered in 1984 by Bryan Small, who recovered the skeleton from a blue mudstone layer in the Chinle Formation's Upper Petrified Forest Member.[3][7][1] Based on U-Pb dating of overlying and underlying units, the mudstone layer was deposited about 213 to 210 million years ago, during the Norian stage of the Triassic.[1]

PEFO 10395 mainly consists of vertebrae, limb bones, and hip fragments. Vertebrae include several partial cervical (neck) dorsal (back), and caudal (tail) vertebrae, along with two sacral (hip) vertebrae, a chevron, and rib fragments. Each of the three bones making up the hip (the ilium, pubis, and ischium) are represented by isolated fragments. Leg bones include a complete right femur, the upper part of the left femur, an incomplete right tibia, and a right astragalus bone of the ankle.[1][3] A single serrated tooth has also been considered as part of the specimen,[8] but this may be in error.[9]

When the holotype specimen was discovered, it was nicknamed "Gertie" (after Gertie the Dinosaur) and received much publicity. "Gertie" was subsequently airlifted by helicopter on June 6, 1985, and brought to the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) in Berkley, CA, where it was prepared over the next several years.[1] The anniversary of the airlift and the media interest it generated for Petrified Forest National Park is celebrated at the park every year. "Gertie" was described and given a proper binomial name by R.A. Long and P.A. Murry in 1995. It was also initially known as the "Chinde Point dinosaur", in reference to a geological landmark close to the site which it was recovered from. This reference was carried over to its generic name, derived from the Navajo word chindi (meaning "ghost" or "evil spirit") and the Greek word "sauros" (σαυρος) (meaning "lizard"). Its name could therefore be translated as "ghost lizard" or "Lizard from Chinde Point". The specific name, bryansmalli, honors the discoverer, Bryan Small.[3]

Referred specimens

Several more incomplete specimens have been referred to the genus. These specimens consist of various vertebrae and femur fragments found throughout the American southwest. Eight referred specimens are stored at PEFO (Petrified Forest National Park, AZ), where the holotype was discovered. Two are stored at the UCMP (University of California Museum of Paleontology), where the holotype was prepared. Up to six more are stored at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNH) in Albuquerque, NM, with at least several of them having been discovered in the Bull Canyon Formation of New Mexico.[9][1] A complete femur, GR 226, was discovered in 2006 at the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch, NM, where it is now stored.[10][1]

Though most specimens referred to Chindesaurus hail from Norian-age formations of Arizona and New Mexico, there are exceptions: TMM 31100-523, which consists of a proximal femur, was discovered in the Carnian-age Colorado City Formation of Texas. It is currently housed in the collections of the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin, TX. A similar case involves UMMP 8870, a partial ilium first described in 1927. It was recovered from the Carnian?-age Tecovas Formation of Texas, and now housed at the University of Michigan (UMMP) in Ann Arbor, MI.[3][1] However, UMMP 8870 may represent a separate species of early dinosaur, Caseosaurus crosbyensis.[8][5] The referred Texas specimens of Chindesaurus were at one point believed to be the oldest dinosaur fossils in the world.[3]

Though specimens referred to Chindesaurus are widely distributed and sometimes well-preserved, none of them exhibit features unique to the genus. The referral of two specimens (NMMNH P16656 and NMMNH P17325) to Chindesaurus came under question as soon as 2007.[9] Marsh et al. (2019) argued that only the holotype specimen of Chindesaurus should be considered as belonging to the genus. They removed all specimens except for the holotype from the genus, placing the rest as indeterminate material from the Chindesaurus + Tawa clade of their analysis.[1]

Description

Long & Murry reconstructed Chindesaurus with a stout body, long legs, a fairly long neck, and a total estimated length of 3 to 4 meters (9.9 to 13.1 feet).[3] Benson & Brusatte (2012) suggested that Chindesaurus was smaller, up to 2 to 2.3 metres (6.6 to 7.5 ft) in length.[11] Holtz (2012) estimated that Chindesaurus had a length of about 2 meters (6.6) feet and a weight equivalent to that of a wolf (23–45 kg, or about 50-100 pounds).[2] The skeletal anatomy of Chindesaurus is incompletely known, so these full body estimates are very rough approximations. The holotype specimen may not be fully grown due to its unfused ankle and dorsal neurocentral sutures. However, these features may not be fully correlated with development in early dinosaurs, and the specimen has other traits indicating a post-juvenile stage, such as a trochanteric shelf and fused caudal neurocentral sutures.[1]

Vertebrae

The cervical (neck) vertebrae, at least near the head, had a low keel along the front half of their lower edge. They also had a pair of shallow oval-shaped depressions on their sides, similar to those found in Tawa, Liliensternus, and Cryolophosaurus. The dorsal (trunk) vertebrae are deep, wide, and fairly short (from front-to-back), closer to the condition in herrerasaurids rather than Tawa and coelophysoids. Both the sides and the lower edge of each dorsal are constricted, and small pockets lie below the sutures with the neural arch. These pockets, known as centrodiapophyseal fossae, are ancestral to dinosaurs but lost by most theropods. Neural spines expand outwards and backwards, forming "spine-tables", structures which are otherwise only observed in Herrerasaurus and Dilophosaurus among potential theropods.[3][9][1]

The two preserved sacral (hip) vertebrae are wide and not fused to each other. The assumption that Chindesaurus had only two sacrals has been vital to its traditional identity as a herrerasaurid.[3] The rear side of the first sacral has a vertical ridge extending up to a large pit, which may be a hypantrum. Large sacral ribs extend outwards from the front half of each sacral vertebrae. The sacral ribs have an inverted T-shaped cross-section when seen from the side. The caudal (tail) vertebrae are large at the base of the tail and elongated towards the tip of the tail. Several low ridges extend towards the prezygapophyses at the front of the distal caudal vertebra. The prezygapophyses themselves are fairly short, unlike those of herrerasaurids or most theropods. A neural spine rises up abruptly in the last third of each caudal. Chevrons curve backwards and are thinnest at their mid-length.[3][1]

Hip and hindlimb

The postacetabular process (rear blade) of the ilium is low, with a horizontal ridge on its inner edge and a large roughly-textured tubercle on its outer surface. These characteristics are also known in Caseosaurus. There is no distinct brevis fossa, also like Caseosaurus and herrerasaurids. Both the pubic and ischiadic peduncles of the ilium expand lengthwise towards their lower edges. Unlike herrerasaurids, the supraacetabular crest of the ilium does not extend as far forwards as its contact with the pubis. The pubis is thin, straight, and slightly curved back, widening slightly towards the ilium. On the other hand, the ischium seems to widen slightly away from the ilium.[9][1]

The femur is large and sigmoid, with a smooth, rectangular femoral head. Like Tawa (but unlike coelophysoids), the anterior trochanter has the appearance of a bulbous ridge, not separated from the shaft by a cleft. However, Chindesaurus lacks a groove at the top of its femoral head, possesses a trochanteric shelf, and has a dorsolateral trochanter which is low and rounded, traits which contrast with Tawa. The fourth trochanter is low and located further distally than that of Herrerasaurus. The lower end of the femur has two distinct condyles which are triangular in cross-section. The tibia is very similar to that of Tawa in several respects. For example, the rear face of the upper end of the tibia is nearly straight, with the exception of a large notch on its medial half and a smaller notch slightly lateral to it. Moreover, the cnemial crest running down the front of the tibia is quite low, <35% the total anteroposterior thickness of the bone. Finally, the lower end of the tibia has a large and triangular posterolateral process which extends downwards and outwards from the rest of the bone, a trait also shared by Lesothosaurus and Guaibasaurus. The front edge of the astragalus has a deep and broad cleft which subdivides the bone vertically. This cleft actually extends onto the lower surface of the bone, giving it a characteristic "glutealiform" shape shared with Tawa. There is a distinct ascending process on the upper and outer part of the astragalus, surrounded by a system of pits, ridges, and depressions which connect to the tibia.[9][1]

Classification

As a herrerasaurid

Chindesaurus has been difficult to classify, and has been recovered in several different positions at the base of the saurischian family tree. When it was first discovered in 1984, the fossil specimen which would eventually be named Chindesaurus was thought to be a "prosauropod" (basal sauropodomorph).[12][3][1] When it was finally described and named a decade later by Long & Murry (1995), they regarded it as a herrerasaurid. This interpretation has been followed by many paleontologists since then, often supported by phylogenetic analyses.[3][4][13][14][15][5]

Nesbitt et al. (2007) and Irmis et al. (2007) argued that Chindesaurus was a probable basal saurischian dinosaur, and noted that it shares a wide range of characteristics with several lineages of basal saurischians, making any classification problematic.[9][10] Rauhut (2003) noted that the medially expanded brevis shelf of Chindesaurus resembles that of "crurotarsans" (pseudosuchians), unlike that of most dinosaurs, which is usually laterally expanded.[16]

A partial ilium originally assigned to Chindesaurus, from the Tecovas Formation of Texas, was later placed in its own genus and species, Caseosaurus crosbyensis, by Hunt et al. (1998).[8] Langer (2004) argued that this separation was probably in error, and that the two forms represent the same species.[17] Nesbitt et al. (2007) corroborated this, stating that the differences between Caseosaurus and Chindesaurus cited by Hunt et al. (1998) were probably a result of size-related variation. However, Nesbitt et al. refrained from formally synonymizing the two taxa due to the fragmentary nature of Chindesaurus's ilium.[9] Baron & Williams redescribed Caseosaurus in 2018, and considered it to be a valid herrerasaurian taxon closely related to, but not within, the family Herrerasauridae, in the larger clade Herrerasauria.[5] An analysis by Novas et al. (in 2021) also placed Chindesaurus as a non-herrerasaurid herrerasaurian, forming a clade with Daemonosaurus and Tawa (also see below)[6]

The following is a cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis by Sues et al. (2011), one of many studies which argued that Chindesaurus is a herrerasaurid.[14]

| Dinosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As a relative of Tawa

A phylogenetic analysis by Cabreira et al. (2016) found an unusual result, where Chindesaurus was placed as the sister taxon of Tawa hallae, a carnivorous dinosaur from the Hayden Quarry of Ghost Ranch in New Mexico.[18] Tawa lived at roughly the same time as the holotype specimen of Chindesaurus, and material referred to Chindesaurus has also been found at the Hayden Quarry.[10][1] Though Chindesaurus was often considered a herrerasaurid and Tawa was often considered a theropod, this study suggested that neither position was correct. Instead, it placed the Chindesaurus + Tawa clade within basal Saurischia, prior to the split between sauropodomorphs and theropods.[18] A Chindesaurus + Tawa clade was also found in a revision to Baron et al. (2017)'s controversial Ornithoscelida hypothesis.[19]

The hypothesis of close relations to Tawa was elaborated upon in 2019, when the holotype specimen of Chindesaurus was redescribed by Adam D. Marsh, William G. Parker, Max C. Langer, and Sterling J. Nesbitt. They included a phylogenetic analysis which placed the Chindesaurus + Tawa clade in the base of Theropoda, a similar position to that first described for Tawa.Their sister-taxon relationship was supported by one apomorphy, or unique derived trait: a posterior margin of the proximal end of the tibia which is divided by two notches. It was also supported by the absence of an oblique ligament sulcus on the rear of the femoral head, a low cnemial crest and prominent posterolateral process of the tibia, and a low astragalus with a prominent anterior groove. The authors noted that two right tibiae from the Cooper Canyon Formation may be referable to this clade based on their possession of two notches on posterior margin of the proximal tibia. Guaibasaurus may also belong to the clade based on its tapering posterolateral process of the distal end of the tibia.[1]

The following cladogram represents the phylogenetic analysis of Marsh et al. (2019), recovering a Chindesaurus + Tawa clade in basal Theropoda:[1]

| Dinosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The Upper Petrified Forest National Park member of the Chinle Formation was an ancient floodplain where phytosaurs, rauisuchids, archosaurs, pseudosuchians, and other tetrapods lived and competed with the dinosaur Chindesaurus and its relative Coelophysis for resources. This paleoenvironment also had abundant lungfish and clams.

References

- Marsh, Adam D.; Parker, William G.; Langer, Max C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2019-05-04). "Redescription of the holotype specimen of Chindesaurus bryansmalli Long and Murry, 1995 (Dinosauria, Theropoda), from Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (3): e1645682. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1645682. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 202865005.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Long, Robert A.; Murry, Phillip A. (1995). "Late Triassic (Carnian and Norian) tetrapods from the Southwestern United States". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 4: 1–254.

- Bittencourt, J.; Kellner, W.A. (2004). "The phylogenetic position of Staurikosaurus pricei from the Triassic of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3, supplement): 39A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643. S2CID 220415208.

- Matthew G. Baron; Megan E. Williams (2018). "A re-evaluation of the enigmatic dinosauriform Caseosaurus crosbyensis from the Late Triassic of Texas, USA and its implications for early dinosaur evolution". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 63. doi:10.4202/app.00372.2017.

- Novas, Fernando E.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Temp Müller, Rodrigo; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Langer, Max C. (October 2021). "Review of the fossil record of early dinosaurs from South America, and its phylogenetic implications". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 110: 103341. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103341.

- Parker, William G.; Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2006). Parker, W. G.; Ash, S. R.; Irmis, R. B. (eds.). "Review of the Late Triassic dinosaur record from Petrified Forest National Park". Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin. 62: 160–161.

- Hunt, A.P.; Lucas, S.G.; Heckert, A.B.; Sullivan, R.M.; Lockley, M.G. (1998). "Late Triassic Dinosaurs from the Western United States". Geobios. 31 (4): 511–531. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(98)80123-X.

- Sterling J. Nesbitt, Randall B. Irmis and William G. Parker (2007). "A critical re-evaluation of the Late Triassic dinosaur taxa of North America". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (2): 209–243. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002040. S2CID 28782207.

- Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Padian, Kevin; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Woody, Daniel; Downs, Alex (2007). "A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs". Science. 317 (5836): 358–361. doi:10.1126/science.1143325. PMID 17641198. S2CID 6050601.

- Benson, R.B.J. & Brusatte, S. (2012). Prehistoric Life. London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- Meyer, (1986). "D-Day on the Painted Desert." Arizona Highways, 62(7): 3–13.

- Nesbitt, S. J.; Smith, N. D.; Irmis, R. B.; Turner, A. H.; Downs, A. & Norell, M. A. (2009), "A complete skeleton of a Late Triassic saurischian and the early evolution of dinosaurs", Science, 326 (5959): 1530–1533, doi:10.1126/science.1180350, PMID 20007898, S2CID 8349110.

- Hans-Dieter Sues; Sterling J. Nesbitt; David S. Berman; Amy C. Henrici (2011). "A late-surviving basal theropod dinosaur from the latest Triassic of North America". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1723): 3459–64. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0410. PMC 3177637. PMID 21490016.

- Baron, Matthew G.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513. S2CID 205254710.

- Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2003). "The Interrelationships and Evolution of Basal Theropod Dinosaur" (PDF). Special Papers in Palaeontology. 69: 1–213.

- Langer, Max C. (2004). "Basal Saurischia" (PDF). In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8. OCLC 55000644. OL 3305845M.

- Cabreira, S.F.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Dias-da-Silva, S.; da Silva, L.R.; Bronzati, M.; de Almeida Marsola, J.C.; Müller, R.T.; de Souza Bittencourt, J.; Batista, B.J.; Raugust, T.; Carrilho, R.; Brodt, A.; Langer, M.C. (2016). "A Unique Late Triassic Dinosauromorph Assemblage Reveals Dinosaur Ancestral Anatomy and Diet". Current Biology. 26 (22): 3090–3095. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.040. PMID 27839975.

- Matthew G. Baron; David B. Norman; Paul M. Barrett (2017). "Baron et al. reply". Nature. 551 (7678): E4–E5. Bibcode:2017Natur.551E...4B. doi:10.1038/nature24012. PMID 29094705. S2CID 205260360.

.jpg.webp)