City of London Corporation

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Kingdom's financial sector.

Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London City of London Corporation | |

|---|---|

Arms of the Corporation of the City of London: Argent, a cross gules in the first quarter a sword in pale point upwards of the last; Supporters: Two dragons with wings elevated and addorsed argent on each wing a cross gules; Crest: On a dragon's wing displayed sinister a cross gules;[1] Motto: Domine Dirige Nos ("O Lord direct us") | |

Corporation logo: a stylised version of the arms | |

| Type | |

| Type | of the City of London |

| Leadership | |

Nicholas Lyons since 11 November 2022 | |

Ian Thomas CBE since February 2023 | |

Policy chairman | Chris Hayward[2] since 5 May 2022 |

Chief Commoner | Ann Holmes |

| Structure | |

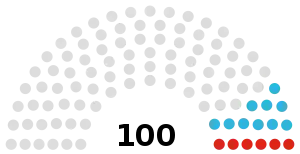

| Seats | 100 Common Councilmen 25 Aldermen |

| |

Court of Common Council political groups |

|

| Court of Aldermen committees | Privileges Committee, General Purposes Committee |

| Court of Common Council committees | List

|

| Elections | |

Last Court of Aldermen election | Varies – individual mandate, up to 6-year term of office |

Last Court of Common Council election | March 2022[3] |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Guildhall, London | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of England on the |

| Politics of London |

|---|

|

In 2006, the name was changed from Corporation of London as the corporate body needed to be distinguished from the geographical area to avoid confusion with the wider London local government, the Greater London Authority.[4]

Both businesses and residents of the City, or "Square Mile", are entitled to vote in City elections, and in addition to its functions as the local authority—analogous to those undertaken by the 32 boroughs that administer the rest of the Greater London region—it takes responsibility for supporting the financial services industry and representing its interests.[5] The corporation's structure includes the Lord Mayor, the Court of Aldermen, the Court of Common Council, and the Freemen and Livery of the City. The "Liberties and Customs" of the City of London are guaranteed in Magna Carta's clause IX, which remains in statute.[6]

History

In the Anglo-Saxon period, consultation between the City's rulers and its citizens took place at the Folkmoot. Administration and judicial processes were conducted at the Court of Husting and the administrative part of the court's work evolved into the Court of Aldermen.[7]

There is no surviving record of a charter first establishing the Corporation as a legal body, but the City is regarded as incorporated by prescription, meaning that the law presumes it to have been incorporated because it has for so long been regarded as such (e.g. Magna Carta states that "the City of London shall have/enjoy its ancient liberties").[8] The City of London Corporation has been granted various special privileges since the Norman Conquest,[9][10] and the Corporation's first recorded royal charter dates from around 1067, when William the Conqueror granted the citizens of London a charter confirming the rights and privileges that they had enjoyed since the time of Edward the Confessor. Numerous subsequent royal charters over the centuries confirmed and extended the citizens' rights.[11]

Around 1189, the City gained the right to have its own mayor, later being advanced to the degree and style of Lord Mayor of London. Over time, the Court of Aldermen sought increasing help from the City's commoners and this was eventually recognised with commoners being represented by the Court of Common Council, known by that name since at least as far back as 1376.[12] The earliest records of the business habits of the City's chamberlains and common clerks, and the proceedings of the courts of Common Council and Aldermen, begin in 1275, and are recorded in fifty volumes known as the Letter-Books of the City of London.[13]

The City of London Corporation had its privileges stripped by a writ quo warranto under Charles II in 1683, but they were later restored and confirmed by Act of Parliament under William III and Mary II in 1690, after the Glorious Revolution.[14]

With growing demands on the Corporation and a corresponding need to raise local taxes from the commoners, the Common Council grew in importance and has been the principal governing body of the City of London since the 18th century.

In January 1898, the Common Council gained the full right to collect local rates when the City of London Sewers Act 1897 transferred the powers and duties of the Commissioners of Sewers of the City of London to the Corporation. A separate Commission of Sewers was created for the City of London after the Great Fire in 1666, and as well as the construction of drains it had responsibility for the prevention of flooding; paving, cleaning and lighting the City of London's streets; and churchyards and burials. The individual commissioners were previously nominated by the Corporation, but it was a separate body. The Corporation had earlier limited rating powers in relation to raising funds for the City of London Police, as well as the militia rate and some rates in relation to the general requirements of the Corporation.

The Corporation is unique among British local authorities for its continuous legal existence over many centuries, and for having the power to alter its own constitution, which is done by an Act of Common Council.[15]

Local authority role

Local government legislation often makes special provision for the City to be treated as a London borough and for the Common Council to act as a local authority. The Corporation does not have general authority over the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple, two of the Inns of Court adjoining the west of the City which are historic extra-parochial areas, but many statutory functions of the Corporation are extended into these two areas.

The chief executive of the administrative side of the Corporation holds the ancient office of Town Clerk of London.

High Officers and other officials

Because of its accumulated wealth and responsibilities, the Corporation has a number of officers and officials unique to its structure who enjoy more autonomy than most local council officials, and each of whom has a separate budget:

- The Town Clerk, who is also the chief executive.

- The Chamberlain, the City Treasurer and Finance Officer.

- The City Remembrancer, who is responsible for protocol, ceremonial, and security issues as well as legislative matters that may affect the Corporation and is legally qualified (usually a barrister).[16]

- The City Surveyor, who is responsible for the central London commercial property portfolio

- The Comptroller and City Solicitor; legal officer.

- The Recorder of London, the senior judge at the Central Criminal Court 'Old Bailey' who is technically a member of the Court of Aldermen; but without precedence, he processes between the senior aldermen, i.e. former lord mayors, and the junior aldermen.

- The Common Serjeant, the second senior judge at the Central Criminal Court ('Old Bailey'), technically the legal adviser to the Common Council (i.e., Serjeant at Law to the Commoners).

There are others:

- The three Esquires at the Mansion House: The City Marshall, the Sword Bearer and the Mace Bearer (who is properly called 'the Common Cryer and Sergeant-at-Arms') run the lord mayor's official residence, his office, and accompany him on all occasions (they are usually senior military officers with diplomatic experience).

- The Chief Commoner who is elected by the Common Councilmen alone and serves for one year until recently chaired all of the Bridge House Estates and property committees but is now honorific.

- The ward beadles are each responsible to the ward by which they are elected, they give largely ceremonial support to their respective ward aldermen, and also perform a formal role at ward motes.

Elections

The first direct elections to Common Council took place in 1384.[17] Before that date the representatives of the wards had been elected by the livery companies; originally they were merely appointed by the aldermen.[18]

The City of London Corporation was not reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, because it had a more extensive electoral franchise than any other borough or city; in fact, it widened this further with its own equivalent legislation allowing one to become a freeman without being a liveryman. In 1801, the City had a population of about 130,000, but increasing development of the City as a central business district led to this falling to below 5,000 after the Second World War.[19] It has risen slightly to around 9,000 since, largely due to the development of the Barbican Estate. As it has not been affected by other municipal legislation over the period of time since then, its electoral practice has become increasingly anomalous.

Therefore, the non-residential vote (or business vote), abolished in the rest of the country in 1969, became an increasingly large part of the electorate. The non-residential vote system used disfavoured incorporated companies. The City of London (Ward Elections) Act 2002 greatly increased the business franchise, allowing many more businesses to be represented. In 2009, the business vote was about 24,000, greatly exceeding residential voters.[20]

Voters

Eligible voters[21] must be at least 18 years old and a citizen of the United Kingdom, or a Commonwealth country, and either:

- A resident;

- A sole trader, or a partner in an unlimited partnership, or;

- An appointee of a qualifying body.

Each body or organisation, whether unincorporated or incorporated, whose premises are within the City of London may appoint a number of voters based on the number of workers it employs. Limited liability partnerships fall into this category.

Bodies employing fewer than ten workers may appoint one voter, those employing ten to fifty workers may appoint one voter for every five; those employing more than fifty workers may appoint ten voters and one additional voter for every fifty workers beyond the first fifty.

Though workers count as part of a workforce regardless of nationality, only certain individuals may be appointed as voters. Under section 5 of the City of London (Ward Elections) Act 2002, the following are eligible to be appointed as voters (the qualifying date is 1 September of the year of the election):

- Those who have worked for the body for the past year at premises in the City;

- Those who have served on the body's board of directors for the past year at premises in the City;

- Those who have worked in the City for the body for an aggregate total of five years;

- Those who have worked mainly in the City for a total of ten years and still do so or have done within the last five years.[22]

Voters appointed by businesses who are also entitled to vote in a local authority district other than the City, due to their residence in that district, maintain the right to vote in their 'home' district.

Wards

The City of London is divided into twenty-five wards, each of which is an electoral division, electing one alderman and a number of councilmen based on the size of the electorate. The numbers below reflect the changes caused by the City of London (Ward Elections) Act and a recent ward boundary review.

| Ward | Common councilmen |

|---|---|

| Aldersgate | 6 |

| Aldgate | 5 |

| Bassishaw | 2 |

| Billingsgate | 2 |

| Bishopsgate | 6 |

| Bread Street | 2 |

| Bridge | 2 |

| Broad Street | 3 |

| Candlewick | 2 |

| Castle Baynard | 8 |

| Cheap | 3 |

| Coleman Street | 4 |

| Cordwainer | 3 |

| Cornhill | 3 |

| Cripplegate | 8 |

| Dowgate | 2 |

| Farringdon Within | 8 |

| Farringdon Without | 10 |

| Langbourn | 3 |

| Lime Street | 4 |

| Portsoken | 4 |

| Queenhithe | 2 |

| Tower | 4 |

| Vintry | 2 |

| Walbrook | 2 |

| Total | 100 |

Livery companies

There are over one hundred livery companies in London. The companies originated as guilds or trade associations. The senior members of the livery companies, known as liverymen, form a special electorate known as Common Hall. Common Hall is the body that chooses the lord mayor, the sheriffs and certain other City officers.

Court of Aldermen

Wards originally elected aldermen for life, but the term is now only six years. Aldermen may, if they so choose, submit to an election before the six-year period ends. In any case, an election must be held no later than six years after the previous election. The sole qualification for the office is that aldermen must be Freemen of the City; candidates are not required to be a resident, leaseholder or freehold owner of land in the ward in which they seek to run, nor even of the City of London.[23]

Alderman serve on the Court of Common Council concurrent with their service on the Court of Alderman. Additionally, they select the Recorder of London, the senior Circuit judge on the Central Criminal Court, who sits on the Court of Alderman, and serve of boards as governors and trustees for various institutions with connections to the city.[24] Alderman are also ex officio justices of the peace.

Court of Common Council

The Court of Common Council, also known as the Common Council of the City of London, is formally referred to as the Mayor, Aldermen, and Commons of the City of London in Common Council assembled.[25] The "Court" is the primary decision-making body of the City of London Corporation and meets nine times per year, though most of its work is carried out by committees.[26]

The Common Council is the police authority for the City of London,[27] a police area that covers the City including the Inner Temple and Middle Temple and which has its own police force – the City of London Police – separate from the Metropolitan Police, which polices the remainder of Greater London.

Each ward may choose a number of common councilmen. A common councilman must be a registered voter in a City ward, own a freehold or lease land in the City, or reside in the City for the year prior to the election. The individual must also be over 21; a Freeman of the City;[28] and a British, Irish, Commonwealth or EU citizen. Common Council elections are held every four years, most recently in March 2022.[3] Common councilmen may use the postnominals CC after their names.

Each year, the common councilmen elect one of their number to serve as Chief Commoner, an honorific office which 'serves to recognise the distinguished contribution the office holder is likely to have made to the City Corporation over a period of years.'[29] The Chief Commoner is expected to champion the Court of Common Council, to work to uphold its rights and privileges, and to offer advice and counsel to its members. They also represent the court on various different committees, support the lord mayor in the business of the Corporation and are prominently present on ceremonial occasions. The Chief Commoner is elected in October of each year and holds office for one year from the following April.

Following a by-election in the Ward of Portsoken on 20 March 2014 the political composition of the Court of Common Council was 99 independent members and one Labour Party member.[30][31] Since City of London Council elections in March 2017, the council has been composed of 95 independents and five Labour Party members.[32] In October 2018, the Labour Party gained its sixth seat on the Common Council with a by-election victory in Castle Baynard ward.[33]

Committees of the City of London

The work of the City of London Corporation is primarily carried out through a range of committees:[34]

- Audit and Risk Management Committee

- Barbican Centre Board

- Barbican Residential Committee

- Board of Governors of the City of London Freemen's School

- Board of Governors of the City of London School

- Board of Governors of the City of London School for Girls

- Board of Governors of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama

- Community & Children's Services Committee

- Culture, Heritage and Libraries Committee

- Education Board

- Epping Forest & Commons Committee

- Establishment Committee

- Finance Committee

- Freedom Applications Committee

- Gresham (City Side) Committee

- Hampstead Heath, Highgate Wood and Queen's Park Committee

- Health and Wellbeing Board

- Investment Committee

- Licensing Committee

- Livery Committee

- Local Government Pensions Board

- Markets Committee

- Open Spaces and City Gardens

- Planning and Transportation Committee

- Police Committee

- Policy and Resources Committee

- Port Health & Environmental Services Committee

- Standards Committee

- The City Bridge Trust Committee

- West Ham Park Committee

The lord mayor and the sheriffs

The Lord Mayor of London and the two sheriffs are chosen by liverymen meeting at Common Hall. Sheriffs, who serve as assistants to the lord mayor, are chosen on Midsummer Day. The lord mayor, who must have previously been a sheriff, is chosen on Michaelmas. Both the lord mayor and the sheriffs are chosen for terms of one year.

The lord mayor fulfills several roles:

- Chairs the Court of Aldermen and the Common Council

- Represents the City to foreign dignitaries

- Heads the Commission of Lieutenancy of the City

- Chief Magistrate of the City

- Admiral of the Port of London

- Chancellor of the City University

- President of Gresham College

- Trustee of Saint Paul's Cathedral

The ancient and continuing office of Lord Mayor of London (with responsibility for the City of London) should not be confused with the office of Mayor of London (responsible for the whole of Greater London and created in 2000). The role of Lord Mayor of London is largely ceremonial; the most senior political position on the City of London Corporation is the chair of the policy and resources committee (also called the policy chairman), sometimes described as the "de facto political leader" of the corporation.[2] The policy chairman represents the City on the leaders' committee of London Councils, alongside the leaders of the 32 London Boroughs.[35]

Ceremonies and traditions

Stuart Fraser, the Corporation's Deputy Policy chairman wrote in 2011 "it is undoubtedly the case that we have more tradition and pageantry than most",[36] for example the yearly Lord Mayor's Show.

There are eight formal ceremonies involving the Corporation:

- Midsummer Common Hall for the election of the sheriffs (24 June or nearest weekday);

- Admission of the Sheriffs, their oath-taking (the nearest weekday to the Michaelmas date);

- Michaelmas Common Hall for the election of the lord mayor (29 September or nearest weekday);

- Admission of the Lord Mayor, the so-called "Silent Ceremony" (Friday before the Lord Mayor's Show);

- Lord Mayor's Show; formally, "the Procession of the Lord Mayor for Presentation to the Lord Chief Justice and King's Remembrancer at the Royal Courts of Justice" (the Saturday after the second Friday in November);

- The Ward Motes; elections in the City wards and general meeting of the ward in non-election years (third Friday in March);

- The Spital Sermon; literally a sermon given in the Guildhall church (St Lawrence Jewry next Guildhall),[37] delivered by a senior cleric on behalf of the Christ's Hospital and Bridewell Hospital (now King Edward's School, Witley) (a day in school term between March and May);

- United Guilds Service involves all of the livery company masters, the lord mayor, sheriffs, the aldermen and high officers. This is the newest having been instituted in 1943, it is the responsibility of a special trust fund operating from Fishmongers' Hall (usually in March but so long as not conflicting with Holy Week).

Temple Bar Ceremony

The historic ceremony of the monarch halting at Temple Bar and being met by the lord mayor, also called the Pearl Sword Ceremony, has often featured in art and literature. It is commented on in televised coverage of modern-day royal ceremonial processions.

Tax journalist Nicholas Shaxson described the ceremony in an article in the New Statesman:[38]

Whenever The Queen makes a State entry to the City, she meets a red cord raised by City police at Temple Bar, and then engages in a colourful ceremony involving the Lord Mayor, his Sword, assorted Aldermen and Sheriffs, and a character called the Remembrancer. In this ceremony, the Lord Mayor recognises The Queen's authority, but the relationship is complex: as the corporation itself says: "The right of the City to run its own affairs was gradually won as concessions were gained from the Crown.

Both the Guildhall Historical Association[39] and Paul Jagger, author of The City of London Freeman's Guide[40] and City of London: Secrets of the Square Mile[41] explain that it is incorrect to say that this is a symbol of the submission of the Crown to the City, with Jagger writing:

The Sovereign does not ask to be admitted. The carriage bearing the King or Queen does not halt without the bar, but drives straight across the boundary and halts just within the City. [...] Can the Press be deflected from their story of the Sovereign asking permission to enter the City! It has been repeated for well over a century. [...] The ceremony is an acknowledgement by the Mayer of the Queen's sovereignty in the City and may take place at the point of entry where it may be. It so happens the entry is most usually at Temple Bar. Wherever the Lord Mayor meets the Sovereign, if the sword is present, it should be surrendered.

Of all the myth and lore that envelopes the Square Mile perhaps none is more persistent than the idea that the Monarch has to ask to enter the City of London and may not do so without the permission of the Lord Mayor. [...] The genesis of this myth is likely to be the Ceremony of the Pearl Sword which has, from time to time, been held at the former site of Temple Bar on Fleet Street. During the ceremony the Monarch's carriage procession draws up, the City Police pull a red cord across the street where Temple Bar once stood, the royal procession stops, the Lord Mayor approaches the carriage and presents the hilt of the City's Pearl Sword to the Monarch who touches it and symbolically returns the sword to the Lord Mayor. This is act of feudal fealty in which the Lord Mayor surrenders his principal symbol of authority to the Monarch, who in turn (assuming she finds him suitably qualified to continue in office) returns the sword.[42]

Conservation areas and green spaces

The City of London Corporation maintains around 10,000 acres (40 km2) of public green spaces[43] – mainly conservation areas / nature reserves – in Greater London and the surrounding counties. The most well-known of the conservation areas are Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest. Other areas include Ashtead Common, Burnham Beeches, Highgate Wood and the City Commons (seven commons in south London).[44][45]

The Corporation also runs the unheated Parliament Hill Lido, in Hampstead Heath which the London Residuary Body with the agreement of the London Boroughs gave into the safekeeping of the City, for the benefit of the public, in 1989.

The City also owns and manages two traditional inner city parks: Queen's Park and West Ham Park as well as over 150 smaller public green spaces. All these green spaces are funded principally by the City of London.[46]

Education

The City of London has a single primary school,[47] The Aldgate School (ages 4 to 11),[48] which is voluntary aided by the Church of England and maintained by the Education Service of the City of London.

City of London residents may send their children to schools in neighbouring local education authorities (LEAs). Some secondary school children enrol in schools in Islington, Tower Hamlets, Westminster or Southwark. Children who are permanent residents of the City of London are eligible for transfer to the City of London Academy, Southwark, a state-funded secondary school sponsored by the City of London located in Bermondsey. The City of London Corporation also sponsors City Academy, Hackney and City of London Academy Islington.

The City of London controls three other private schools – the City of London School (for boys), the City of London School for Girls, and the co-educational City of London Freemen's School. The Lord Mayor also holds the posts of Rector of City University and President of Gresham College, an educational institution for advanced study.

The Guildhall School of Music and Drama is owned and funded by the Corporation.

Criticism

Writing in The Guardian, George Monbiot claimed that the corporation's power "helps to explain why regulation of the banks is scarcely better than it was before the crash, why there are no effective curbs on executive pay and bonuses and why successive governments fail to act against the UK's dependent tax havens" and suggested that its privileges could not withstand proper "public scrutiny".[49]

In December 2012, following criticism that it was insufficiently transparent about its finances, the City of London Corporation revealed that its "City's Cash" account – an endowment fund built up over the past 800 years that it says is used "for the benefit of London as a whole"[50] – holds more than £1.3bn. As of March 2016, it had net assets of £2.3bn.[51] The fund collects money made from the corporation's property and investment earnings.[52]

See also

References

- "The Heraldic Dragon". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "New political leader for Square Mile as Hayward takes vital Corporation role". City A.M. 5 May 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "2022 City elections results". The City of London Corporation. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- The body was popularly known as the Corporation of London but on 10 November 2005 the Corporation announced Archived 23 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine that its informal title would from 3 January 2006 be the City of London (or the City of London Corporation where the corporate body needed to be distinguished from the geographical area). This may reduce confusion between the Corporation and the Greater London Authority.

- "History and Heritage". City of London website. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "Magna Carta (1297)". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "The Civic Courts of the City of London". London Metropolitan Archives. p. 2. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Lambert, Matthew (2010). "Emerging First Amendment Issues. Beyond Corporate Speech: Corporate Powers in a Federalist System" (PDF). Rutgers Law Record. 37 (Spring): 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "Development of local government". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "The Corporation of London, its rights and privileges". Wattpad.com. 6 January 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "Corporation of London: Administrative history". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "History of the Government of the City of London". Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Sharpe, Reginald R., ed. (1899). Introduction. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Statute of William and Mary, confirming the Privileges of the Corporation". A New History of London Including Westminster and Southwark. London: R. Baldwin. 1773. pp. 860–863. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012 – via British History Online.

- "Information Leaflet Number 13" (PDF). London Metropolitan Archives. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2012.

- "About the City". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Stevens, Andrew (12 August 2014). "The City of London offers on one square mile history, feudal governance and global finance". City Mayors. The City Mayors Foundation.

- "The Court of Common Council" (PDF). London Metropolitan Archives. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "City of London: Total Population". Vision of Britain Through Time. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- René Lavanchy (12 February 2009). "Labour runs in City of London poll against 'get-rich' bankers". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- "Voting and Registration FAQ". City of London Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- "Worker Registration". City of London Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012.

- "City of London Wardmote Book (2021)" (PDF). City of London Corporation. cityoflondon.gov.uk/. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Guidance for election as an Alderman and Guidance on Progression to the Offices of Sheriff and Lord Mayor" (PDF). cityoflondon.uk.gov/. City of London Corporation. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- Example usage: interpretation clause in the Open Spaces Act 1906 Archived 10 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Committee details – Court of Common Council". democracy.cityoflondon. City of London. 28 October 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011". Government of the United Kingdom. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Qualifying criteria for a Common Councillor" (PDF). City of London Corporation.

A person must also be a Freeman of the City of London, this can be granted quickly for potential candidates.

- "Job description" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "Election results". Archived from the original on 25 September 2014.

- "Your Councillors". 15 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Thompson, Jennifer (24 March 2017). "Labour scores record win in City of London election". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "Natasha Lloyd-Owen wins Castle Baynard by-election". Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Committee details – Court of Aldermen". Government of the United Kingdom. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Your Councillors". City of London Corporation. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Fraser, Stuart (28 September 2007). "Response: The City of London is not above the law. Our elections are free and fair". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Spital Sermon". St Lawrence Jewry. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Shaxson, Nicholas (24 February 2011). "The tax haven in the heart of Britain". New Statesman issue, The offshore City. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Jones, P. E. (11 July 1955). The Surrender of the Sword (PDF). Guildhall Historical Association.

- Jagger, Paul David (2017). The City of London Freeman's Guide. The Information Technologists' Company. ISBN 978-0-9566011-2-4.

- Jagger, Paul (2018). City of London: Secrets of the Square Mile. Pitkin. ISBN 978-1-84165-803-2.

- Jagger, Paul (15 January 2018). "The City's relationship with the Monarch and the Royal Family". City and Livery.

- Ramblers. "Corporation of London Open Spaces | Ramblers, Britain's Walking Charity". Ramblers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 August 2002. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Ramblers. "Corporation of London Open Spaces". Ramblers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Green spaces". City of London. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Management of our Green Spaces". City of London Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- Cityoflondon.gov.uk Archived 5 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Cityoflondon.gov.uk Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Monbiot, George (31 October 2011). "The medieval, unaccountable Corporation of London is ripe for protest". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "City of London funds". City of London website. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015.

- "City's Cash Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year ended 31 March 2016" (PDF). www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. Corporation of the City of London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Rawlinson, Kevin (20 December 2012). "City of London Corporation to reveal details of £1.3bn private account". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Green spaces run by the City of London

- London Metropolitan Archives Leaflet on the Court of Common Council