Gifford Pinchot National Forest

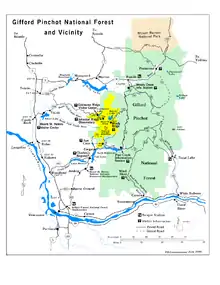

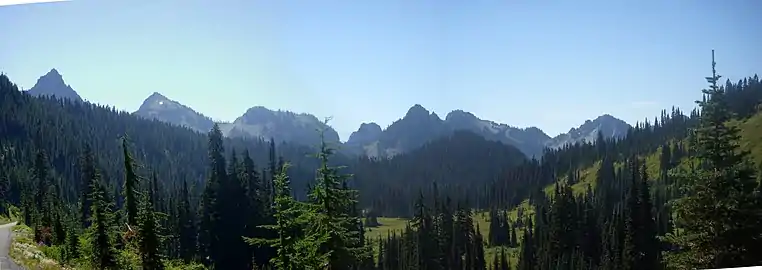

Gifford Pinchot National Forest is a National Forest located in southern Washington, managed by the United States Forest Service. With an area of 1.32 million acres (5300 km2), it extends 116 km (72 mi) along the western slopes of Cascade Range from Mount Rainier National Park to the Columbia River. The forest straddles the crest of the South Cascades of Washington State, spread out over broad, old growth forests, high mountain meadows, several glaciers, and numerous volcanic peaks. The forest's highest point is at 12,276 ft (3,742 m) at the top of Mount Adams, the second tallest volcano in the state after Rainier. Often found abbreviated GPNF on maps and in texts, it includes the 110,000-acre (450 km2) Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, established by Congress in 1982.

| Gifford Pinchot National Forest | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Washington, US |

| Nearest city | Amboy, Washington |

| Coordinates | 46°10′N 121°49′W[1] |

| Area | 1,321,506 acres (5,347.95 km2)[2] |

| Established | July 1, 1908[3] |

| Visitors | 1,800,000 (in 2005) |

| Governing body | U.S. Forest Service |

| Website | https://www.fs.usda.gov/giffordpinchot/ |

History

Gifford Pinchot National Forest is one of the older national forests in the United States. Included as part of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve in 1897, 941,440 acres (3,809.9 km2) was set aside as the Columbia National Forest on July 1, 1908.

In 1855, the US government commissioned Washington Territory to negotiate land cession treaties with tribes around the forest. The Yakama tribe signed a treaty agreement that stipulated their moving to a reservation while maintaining off-reservation resource rights; however, the original treaty was then broken in 1916 when the Washington State Supreme Court ruled that Yakamas' hunting off the reservation had to subscribe to state fish and game laws. Many tribes in the area have continued to use the area's resources while encountering non-Native hunters, fishers, and recreation users.[4]

It was later renamed the Gifford Pinchot National Forest on June 15, 1949, in honor of Gifford Pinchot, one of the leading figures in the creation of the national forest system of the United States. His widow and fellow conservationist, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, was one of the speakers who addressed the audience assembled that day.[5] In 1985 the non-profit Gifford Pinchot Task Force formed to promote conservation of the forest.

Geography

Gifford Pinchot National Forest is located in a mountainous region approximately between Mount St. Helens to the west, Mount Adams to the east, Mount Rainier National Park to the north, and the Columbia River to the south. This region of Southwest Washington is noted for its complex topography and volcanic geology. About 65 percent of the forest acreage is located in Skamania County. In descending order of land area the others are Lewis, Yakima, Cowlitz, and Klickitat counties.[6]

Major rivers

The Pacific Northwest brings abundant rainfall to the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, feeding an extensive network of rivers. The forest has only one river currently designated as Wild and Scenic, the White Salmon River, fed from glaciers high on Mount Adams. The Gifford Pinchot National Forest recommends four rivers to be added to the Wild and Scenic System. They are the Lewis River, the Cispus River, the Clear Fork and the Muddy Fork of the Cowlitz River. There are an additional thirteen rivers in the forest being studied for consideration into the national Wild and Scenic River System.[7]

The following listed are the major streams and rivers of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Many of these provide excellent fishing.[8]

- Cispus River

- Cowlitz River

- White Salmon River

- Little White Salmon River

- Wind River

- Lewis River

- Muddy River

- East Canyon Creek

- Skate Creek

- Iron Creek

- Trout Lake Creek

- Cultus Creek

- Quartz Creek

- Butter Creek

- Clear Creek

- Siouxon Creek

- Canyon Creek

- Johnson Creek

Major lakes

The Gifford Pinchot National Forest includes many popular and secluded backcountry lakes. Most of the lakes offers excellent fishing. Goose Lake is known for the best fishing in the State of Washington.

The following table lists the major lakes of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest:[9]

Congressional action

Congressional action since 1964 has established one national monument and seven wilderness areas in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

National Monuments

On August 26, 1982, congressional action established the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, after the cataclysmic eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980.

Wilderness Areas

Congressional action since 1964 has established the following wilderness areas:

- Glacier View Wilderness – 3,060 acres (12.4 km2)[10]

- Goat Rocks – 108,020 acres (437.1 km2), part of which lies in neighboring Wenatchee NF[11]

- Indian Heaven – 20,782 acres (84.1 km2)

- Mount Adams – 47,078 acres (190.5 km2)

- Tatoosh – 15,725 acres (63.6 km2)

- Trapper Creek – 5,969 acres (24.2 km2)

- William O. Douglas – 168,955 acres (683.7 km2), most of which lies in neighboring Wenatchee NF[12]

- The Shark Rock Wilderness was proposed in the mid-1970s by E.M. Sterling for the 75,000 acre Dark Divide Roadless Area in his book, The South Cascades. It is the largest unprotected roadless area (allowing motorized access) in the Washington Cascades, featuring sharp peaks and deep canyons, old growth forests, and delicate subalpine meadows.[13]

Points of interest

The forest also offers the following special areas and points of interest:[14]

- Dark Divide Roadless Area

- Silver Star Scenic Area

- Lava tubes, caves, and casts (notably the Ice Caves)

- Ape Caves

- Midway High Lakes Area

- Big Lava Bed

- Packwood Lake

- Sawtooth Berry Fields, huckleberry fields reserved for Yakima tribe use.[15] Designated in 1932 through a handshake agreement between forest supervisor J.R. Bruckart and Yakima Chief William Yallup.[16]

- Lone Butte Wildlife Emphasis Area

- Layser cave, a dwelling for Native Americans 7,000 years ago and a former archeological site.[17]

Forest Service management

The forest supervisor's office is located in Vancouver, Washington. There are local ranger district offices in Randle, Amboy, and Trout Lake.[18] The forest is named after the first chief of the United States Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot. Washington towns near entrances of the forest include Cougar, Randle, Packwood, Trout Lake, and Carson.

Ecology

A 1993 Forest Service study estimated that the extent of old growth in the Forest was 198,000 acres (80,000 ha), some of which is contained within its wilderness areas.[19]

The Gifford Pinchot National Forest is the native habitat for several threatened species which include the spotted owl (threatened 2012)[20] as well as multiple species of Northwest fish like the bull trout (threatened 1998),[21] chinook salmon (threatened 2011), coho salmon (threatened 2011) and steelhead (threatened 2011).[22]

People for over 6,000 years have made an impact in the ecology of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.[14] Native Americans hunted in high meadows below receding glaciers. The natives then began to manage the forest to meet their own needs. One method they used was to burn specific areas to help in the huckleberry production. About 338 spots more than 6,000 culturally modified trees were identified, of which 3,000 are protected now. Archaeological investigations are supported by the United States Forest Service.[14]

The forest was home to the Big Tree at the southern flank of Mt Adams, one of the world's largest Ponderosa Trees.

See also

References

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- "Land Areas of the National Forest System" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service. January 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- "The National Forests of the United States" (PDF). ForestHistory.org. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- Catton, Theodore (2017). American Indians and National Forests. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816536511.

- Davis, Richard C. (September 29, 2005), National Forests of the United States (PDF), The Forest History Society, archived from the original (PDF) on October 28, 2012

- "Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County". United States Forest Service. October 10, 2007. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest – Wild and Scenic Rivers". Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest – Streams and Rivers". Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest - Recreation".

- "Glacier View Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- "Goat Rocks Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- "William O. Douglas Wilderness". Wilderness Connect. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- "Dark Divide". Washington Trails Association. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- "About the Forest". Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- "Indian Heaven Wilderness – Subsection: Northwest Tribes". Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Otto, Terry (5 September 2018). "Sawtooth Berry Fields offer late-season treats for huckleberry hunters". The Columbian. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- "Gifford Pinchot National Forest - Interpretive Site: Layser Cave".

- "USFS Ranger Districts by State" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- Bolsinger, Charles L.; Waddell, Karen L. (1993), Area of old-growth forests in California, Oregon, and Washington (PDF), United States Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Resource Bulletin PNW-RB-197

- "Species Profile-Northern Spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- "Species Profile-Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- "5-Year Review: Summary & Evaluation of Lower Columbia River Chinook, Columbia River Chum, Lower Columbia River Coho, Lower Columbia River Steelhead" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-03.