Destination sign

A destination sign (North American English) or destination indicator/destination blind (British English) is a sign mounted on the front, side or rear of a public transport vehicle, such as a bus, tram/streetcar or light rail vehicle, that displays the vehicle's route number and destination, or the route's number and name on transit systems using route names. The main such sign, mounted on the front of the vehicle, usually located above (or at the top of) the windshield, is often called the headsign, most likely from the fact that these signs are located on the front, or head, end of the vehicle. Depending on the type of the sign, it might also display intermediate points on the current route, or a road that comprises a significant amount of the route, especially if the route is particularly long and its final terminus by itself is not very helpful in determining where the vehicle is going.

Technology types

Several different types of technology have been used for destination signs, from simple rigid placards held in place by a frame or clips, to rollsigns, to various types of computerized, and more recently electronically controlled signs, such as flip-dot, LCD or LED displays. All of these can still be found in use today, but most transit-vehicle destination signs now in use in North America and Europe are electronic signs. In the US, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 specifies certain design criteria for transit-vehicle destination signs, such as maximum and minimum character height-to-width ratio and contrast level, to ensure the signs are sufficiently readable to visually impaired persons.[1][2] In the 2010s, LED signs have replaced flip-dot signs as the most common type of destination sign in new buses and rail transit vehicles.[3]

Rollsign

For many decades, the most common type of multiple-option destination sign was the rollsign (or bus blind, curtain sign, destination blind, or tram scroll): a roll of flexible material with pre-printed route number/letter and destinations (or route name), which is turned by the vehicle operator at the end of the route when reversing direction, either by a hand crank or by holding a switch if the sign mechanism is motorized. These rollsigns were usually made of linen until Mylar (a type of PET film) became the most common material used for them,[4] in the 1960s/70s. They can also be made of other material, such as Tyvek.

In the 1990s rollsigns were still commonly seen in older public transport vehicles, and were sometimes used in modern vehicles of that time.[1] Since the 1980s, they have largely been supplanted by electronic signs.[1] A digital display may be somewhat less readable, but is easier to change between routes/destinations and to update for changes to a transit system's route network. However, given the long life of public transit vehicles and of sign rolls, if well made, some transit systems continue to use these devices in the present day.

The roll is attached to metal tubes at the top and bottom, and flanges at the ends of the tubes are inserted into a mechanism which controls the rolling of the sign. The upper and lower rollers are positioned sufficiently far apart to permit a complete "reading" (a destination or route name) to be displayed, and a strip light is located behind the blind to illuminate it at night.

When the display needs to be changed, the driver/operator/conductor turns a handle/crank—or holds a switch if the sign mechanism is motorized—which engages one roller to gather up the blind and disengages the other, until the desired display is found. A small viewing window in the back of the signbox (the compartment housing the sign mechanism) permits the driver to see an indication of what is being shown on the exterior.

Automatic changing of rollsign/blind displays, through electronic control, has been possible since at least the 1970s, but is an option that primarily has been used on rail systems—where a metro train or articulated tram can have several separate signboxes each—and only infrequently on buses, where it is comparatively easy for the driver to change the display. These signs are controlled by a computer through an interface in the driver's cabin. Barcodes are printed on the reverse of the blind, and as the computer rolls the blind an optical sensor reads the barcodes until reaching the code for the requested display. The on-board computer is normally programmed with information on the order of the displays, and can be programmed using the non-volatile memory should the blind/roll be changed. Although these sign systems are normally accurate, over time the blind becomes dirty and the computer may not be able to read the markings well, leading occasionally to incorrect displays. For buses, this disadvantage is outweighed by the need (compared to manual) to change each destination separately; if changing routes, this could be up to seven different blinds. Automatic-setting rollsigns are common on many light rail and subway/metro systems in North America. Most Transport for London buses use a standard system with up & down buttons to change the destination shown on the blinds & a manual override using a crank. The blind system is integrated with a system controlling announcements & passenger information, which uses satellites to download stop data in a sequential order. It uses GPS to determine that a bus has departed a stop, and announce the next stop.

Plastic sign

Plastic signs are inserted by the driver into the slot at the front of the bus before a service run. In Hong Kong, plastic signs had been used since the mid-90s on Kowloon Motor Bus (KMB) and Long Win Bus (LWB) buses to replace rollsigns on the existing fleet, and became a standard equipment until 2000 when electronic display became mainstream, with the exception of single decker buses, presumably because the number of destinations in the network was so large that rolling the destination between every trip was impractical.

These buses were equipped with a destination sign slot which 2 plastic destination signs could be placed in it, such that the driver could press a button to flip them at the terminus, and one slot at the front, side and back of the bus respectively for the route number only.

All buses with plastic signs were retired in 2017 upon completing 18 years of service.

Flip-disc display

In the United States, the first electronic destination signs for buses were developed by Luminator in the mid-1970s[1] and became available to transit operators in the late 1970s, but did not become common until the 1980s. These were flip-disc, or "flip-dot", displays. Some transit systems still use these today.

Flap display

Another technology that has been employed for destination signs is the split-flap display, or Solari display, but outside Italy, this technology was never common for use in transit vehicles. Such displays were more often used at transit hubs to display arrival and departure information, rather than as destination signs on transit vehicles.

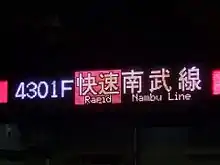

Electronic displays

Starting in the early 1990s, and becoming the primary type of destination sign by the end of the decade, electronic displays consist of liquid crystal display (LCD) or light-emitting diode (LED) panels that can show animated text, colors (in the case of LED signs), and a potentially unlimited number of routes (so long as they are programmed into the vehicle's sign controller unit; some sign controller units may also allow the driver to write the route number and the destination text through a keypad if required). In many systems, the vehicle has three integrated signs in the system, the front sign over the windshield, the side sign over the passenger entrance, both showing the route number and destination, and a rear sign usually showing the route number. An internal sign, that could also provide different kinds of information such as the current stop and the next one, aside from the route number and destination, may also be installed.

Some such signs also have the capability of changing on-the-fly as the vehicle moves along its route, with the help of GPS technology, serial interfaces and a vehicle tracking system.[3]

See also

References

- "Sign of the Times: Transit signs have evolved from curtain signs to the first electronic sign introduced by Luminator to the present ADA-regulated visual and audio signs". Mass Transit magazine, January–February 1993, pp. 30–32. Fort Atkinson, WI (USA): Cygnus Publishing. ISSN 0364-3484.

- Destination and route signs (guidelines for), section 39 within Part 38 (Accessibility Specifications for Transportation Vehicles) of the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

- Tucker, Joanne (September 2011). "The Wireless Age for Digital Destination Signage Arrives". Metro Magazine. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Krambles, George (Winter 1996–97). "Helvetica and Transit". The New Electric Railway Journal. p. 38. ISSN 1048-3845.

External links

Rollsign Gallery, showing the history of public transit through their destination signs – USA, Canada, overseas: www.rollsigngallery.com

.jpg.webp)