Hackney carriage

A hackney or hackney carriage (also called a cab, black cab, hack or London taxi) is a carriage or car for hire.[5] A hackney of a more expensive or high class was called a remise.[6] A symbol of London and Britain, the black taxi is a common sight on the streets of the UK.[7] The hackney carriages carry a roof sign TAXI that can be illuminated at night to indicate their availability for passengers.[8]

In the UK, the name hackney carriage today refers to a taxicab licensed by the Public Carriage Office, local authority (non-metropolitan district councils, unitary authorities) or the Department of the Environment depending on region of the country.[9]

In the United States, the police department of the city of Boston has a Hackney Carriage Unit, analogous to taxicab regulators in other cities, that issues Hackney Carriage medallions to its taxi operators.[10]

Etymology

The origins of the word hackney in connection with horses and carriages are uncertain. The origin is often attributed to the London borough of Hackney, whose name likely originated in Old English meaning 'Haka's Island'. There is some doubt whether the word for a horse was derived from this place-name, as the area was historically marshy and not well-suited for keeping horses.[11] The American Hackney Horse Society favours an alternative etymology stemming from the French word haquenée—a horse of medium size recommended for lady riders—which was brought to England with the Norman Conquest and became fully assimilated into the English language by the start of the 14th century. The word became associated with an ambling horse, usually for hire.

The place-name, through its famous association with horses and horse-drawn carriages, is also the root of the Spanish word jaca, a term used for a small breed of horse[12] and the Sardinian achetta horse. The first documented hackney coach—the name later extended to the newer and smaller carriages—operated in London in 1621.

The New York City colloquial terms "hack" (taxi or taxi-driver), hackstand (taxi stand), and hack license (taxi licence) are probably derived from hackney carriage. Such cabs are now regulated by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission.

History

| Hackney Coaches, etc. Act 1694 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act for the lycenseing and regulateing Hackney-Coaches and Stage-Coaches. |

| Citation | 5 & 6 Will. & Mar. c. 22 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 25 April 1694 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Statute Law Revision Act 1867 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Hackney Chairs Act 1712 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act for explaining the Acts for licensing Hackney Chairs. |

| Citation | 12 Ann. c. 15

|

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 16 July 1713 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Hackney Coaches, etc. Act 1715 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1771 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Hackney Coachmen Act 1771 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1772 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to explain and amend an Act, made in the Seventh Year of the Reign of His present Majesty, intituled, "An Act for altering the Stamp Duties upon Policies of Assurances; and for reducing the Allowance to be made in respect of the Prompt Payment of the Stamp Duties on Licences for retailing Beer, Ale, and other exciseable Liquors; and for explaining and amending several Acts of Parliament relating to Hackney Coaches and Chairs;" so far as the same relates to Hackney Coaches. |

| Citation | 12 Geo. 3. c. 49 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1784 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act for laying an additional Duty on Hackney Coaches, and for explaining and amending several Acts of Parliament relating to Hackney Coaches. |

| Citation | 24 Geo. 3. Sess. 2. c. 27 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 13 August 1784 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1786 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1792 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| London Hackney Carriage Act 1800 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Citation | 39 & 40 Geo. 3. c. 47 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Hackney Coaches Act 1804 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act for explaining and amending several Acts relating to Hackney Coaches employed as Stage Coaches, and for indemnifying the Owners of Hackney Coaches who have omitted to take out Licences, pursuant to an Act made in the twenty-fifth Year of his present Majesty. |

| Citation | 44 Geo. 3. c. 88 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 20 July 1804 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Hackney Carriages Act 1815 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act to amend several Acts relating to Hackney Coaches; for authorizing the licensing of an additional Number of Hackney Chariots; and for licensing Carriages drawn by One Horse. |

| Citation | 55 Geo. 3. c. 159 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 11 July 1815 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 |

Status: Repealed | |

| London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to amend the Laws relating to Hackney Carriages, and to Waggons, Carts, and Drays, used in the Metropolis; and to place the Collection of the Duties on Hackney Carriages and on Hawkers and Pedlars in England under the Commissioners of Stamps. |

| Citation | 1 & 2 Will. 4. c. 22 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 22 September 1831 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repeals/revokes |

|

| Amended by |

|

Status: Amended | |

| Text of the London Hackney Carriage Act 1831 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. | |

| London Hackney Carriages Act 1843 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| London Cab Act 1968 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

| London Cab Act 1973 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) |

The widespread use of private coaches by the English aristocracy began to be seen in the 1580s; within fifty years hackney coaches were regularly to be seen on the streets of London. In the 1620s there was a proliferation of coaches for hire in the metropolis, so much so that they were seen as a danger to pedestrians in the narrow streets of the city, and in 1635 an Order in Council was issued limiting the number allowed. Two years later a system for licensing hackney coachmen was established (overseen by the Master of the Horse).[13]

"An Ordinance for the Regulation of Hackney-Coachmen in London and the places adjacent" was approved by Parliament in 1654, to remedy what it described as the "many Inconveniences [that] do daily arise by reason of the late increase and great irregularity of Hackney Coaches and Hackney Coachmen in London, Westminster and the places thereabouts".[14] The first hackney-carriage licences date from a 1662 Act of Parliament (the Streets, London and Westminster Act 1662, 14 Cha. 2. c. 2) establishing the Commissioners of Scotland Yard to regulate them. Licences applied literally to horse-drawn carriages, later modernised as hansom cabs (1834), that operated as vehicles for hire. The 1662 act limited the licences to 400; when it expired in 1679, extra licences were created until a 1694 act imposed a limit of 700.[15] The limit was increased to 800 in 1715, 1,000 in 1770 and 1,100 in 1802, before being abolished in 1832.[16] The 1694 Act established the Hackney Coach Commissioners to oversee the regulation of fares, licences and other matters; in 1831 their work was taken over by the Stamp Office and in 1869 responsibility for licensing was passed on to the Metropolitan Police. In the 18th and 19th centuries, private carriages were commonly sold off for use as hackney carriages, often displaying painted-over traces of the previous owner's coat of arms on the doors.[17]

There was a distinction between a general hackney carriage and a hackney coach, which was specifically a hireable vehicle with four wheels, two horses and six seats: four on the inside for the passengers and two on the outside (one for a servant and the other for the driver, who was popularly termed the Jarvey (also spelled jarvie)). For many years only coaches, to this specification, could be licensed for hire; but in 1814 the licensing of up to 200 hackney chariots was permitted, which carried a maximum of three passengers inside and one servant outside (such was the popularity of these new faster carriages that the number of licences was doubled the following year).

Shortly afterwards even lighter carriages began to be licensed: the two-wheel, single-horse cabriolets or 'cabs', which were licensed to carry no more than two passengers.[13] Then, in 1834, the hansom cab was patented by Joseph Hansom: a jaunty single-horse, two-wheel carriage with a distinctive appearance, designed to carry passengers safely in an urban environment. The hansom cab quickly established itself as the standard two-wheel hackney carriage and remained in use into the 20th century.[17]

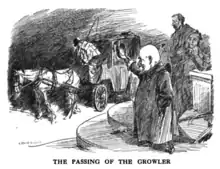

In 1836 the Clarence was introduced to London's streets: a type of small four-wheel enclosed carriage drawn by one or two horses.[18][19] These became known as 'growlers' because of the sound they made on the cobbled streets. Much slower than a hansom cab, they nevertheless had room for up to four passengers (plus one servant) and space on the roof for luggage. As such they remained in use as the standard form of four-wheeled hackney carriage until replaced by motorised taxi cabs in the early 20th century.

A small, usually two-wheeled, one-horse hackney vehicle called a noddy once plied the roads in Ireland and Scotland. The French had a small hackney coach called a fiacre.

Motorisation

Electric hackney carriages appeared before the introduction of the internal combustion engine to vehicles for hire in 1897. In fact there was even London Electrical Cab Company: the cabs were informally called Berseys after the manager who designed them, Walter Bersey. Another nickname was Hummingbirds from the sound that they made.[20] In August 1897, 25 were introduced, and by 1898, there were 50 more. During the early 20th century, cars generally replaced horse-drawn models. In 1910, the number of motor cabs on London streets outnumbered horse-drawn growlers and hansoms for the first time. At the time of the outbreak of World War I, the ratio was seven to one in favor of motorized cabs.[21] The last horse-drawn hackney carriage ceased service in London in 1947.[22]

UK regulations define a hackney carriage as a taxicab allowed to ply the streets looking for passengers to pick up, as opposed to private hire vehicles (sometimes called minicabs), which may pick up only passengers who have previously booked or who visit the taxi operator's office. In 1999, the first of a series of fuel cell powered taxis were tried out in London. The "Millennium Cab" built by ZeTek gained television coverage and great interest when driven in the Sheraton Hotel ballroom in New York by Judd Hirsch, the star of the television series Taxi. ZeTek built three cabs but ceased activities in 2001.

Continuing horse-drawn cab services

Horse-drawn hackney services continue to operate in parts of the UK, for example in Cockington, Torquay.[23] The town of Windsor, Berkshire, is believed to be the last remaining town with a continuous lineage of horse-drawn hackney carriages, currently run by Orchard Poyle Carriages, the licence having been passed down from driver to driver since 1830.

The Royal Borough now licences the carriage for rides around Windsor Castle and the Great Park; however, the original hackney licence is in place, allowing for passenger travel under the same law that was originally passed in 1662. The city of Bath has an occasional horse-drawn Hackney, principally for tourists, but still carrying hackney plates.

Black cabs

Though there has never been law requiring London's taxis to be black, they were, since the end of the Second World War, sold in a standard colour of black. This, in the 1970s gave rise within the minicab trade to the nickname 'black cab' and it has become common currency. However, before Second World War, London's cabs were seen in a variety of colours. They are produced in a variety of colours, sometimes in advertising brand liveries (see below). Fifty golden cabs were produced for the Queen's Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002.[24]

Vehicle design

In Edwardian times, French-manufactured automobiles represented the overwhelming majority of London's motor cab trade, with Renault and Unic being the most common. Not only Renault and Unic, but also smaller players like Charron and Darracq were to be found.[21] Fiat was also a presence, with their importer d'Arcy Baker running a fleet of 400 cars of the brand. In the 1920s, Beardmore cabs were introduced and became for a while the most popular. They were nicknamed 'the Rolls-Royce of cabs' for their comfort and robustness. The American Yellow Cabs also appeared, though only in small numbers. Maxwell Monson introduced Citroën cabs, which were cheaper, but crude in comparison to the Beardmore. In 1930 dealers Mann and Overton struck a deal with the Austin to bring modified version of the Austin 12/4 car to the London taxi market. This established the Austin make as dominant until the end of the 1970s and Mann and Overton until 2012. Morrises cabs were also seen, in small numbers, but after the Second World War, produced the Oxford, made by Wolseleys,[21]

Outside of London, the regulations governing the hackney cab trade are different. Four-door saloon cars have been highly popular as hackney carriages, but with disability regulations growing in strength and some councils offering free licensing for disabled-friendly vehicles, many operators are now opting for wheelchair-adapted taxis such as the LEVC TX of London Electric Vehicle Company (LEVC). London taxis have broad rear doors that open very wide (or slide), and an electrically controlled ramp that is extended for access.[25] Other models of specialist taxis include the Peugeot E7 and rivals from Fiat, Ford, Volkswagen, and Mercedes-Benz. These vehicles normally allow six or seven passengers, although some models can accommodate eight. Some of these minibus taxis include a front passenger seat next to the driver, while others reserve this space solely for luggage.

London taxis must have a turning circle not greater than 8.535 m (28 ft). One reason for this is the configuration of the famed Savoy Hotel: the hotel entrance's small roundabout meant that vehicles needed the small turning circle in order to navigate it. That requirement became the legally required turning circles for all London cabs, while the custom of a passenger's sitting on the right, behind the driver, provided a reason for the right-hand traffic in Savoy Court, allowing hotel patrons to board and alight from the driver's side.[26]

The design standards for London taxis are set out in the Conditions of Fitness, which are now published by Transport for London. The first edition was published in May 1906, by the Public Carriage Office, which was then part of the Metropolitan Police. These regulations set out the conditions under which a taxi may operate and have been updated over the years to keep pace with motor car development and legislation. Changes include regulating the taximeter (made compulsory in 1907), advertisements and the turning circle of 8.535 m (28 ft).[20][27] Until the beginning of the 1980s, London Taxis were not allowed to carry any advertisements.[21] The London Taxis fleet has been fully accessible since 1 January 2000,[28][29] following the introduction of the first accessible taxi in 1987.[30]

As part of the Transported by Design programme of activities,[31] on 15 October 2015, after two months of public voting, the black cab was elected by Londoners as their favourite transport design icon.[32][33]

Driver qualification

In London, hackney-carriage drivers have to pass a test called The Knowledge to demonstrate that they have an intimate knowledge of the geography of London streets, important buildings, etc. Learning The Knowledge allows the driver to become a member of the Worshipful Company of Hackney Carriage Drivers. There are two types of badge, a yellow one for the suburban areas and a green one for all of London. The latter is considered far more difficult. Drivers who own their cabs as opposed to renting from a garage are known as "mushers" and those who have just passed the "knowledge" are known as "butter boys".[34] There are currently around 21,000 black cabs in London, licensed by the Public Carriage Office.[35]

Elsewhere, councils have their own regulations. Some merely require a driver to pass a DBS disclosure and have a reasonably clean driving licence, while others use their own local versions of London's The Knowledge test.

Notable drivers

- Alfred Collins, who retired in 2007 at the age of 92, was the oldest cab driver and had been driving for 70 years.[36]

- Fred Housego is a former London taxi driver who became a television and radio personality and presenter after winning the BBC television quiz Mastermind in 1980.[37][38]

- Clive Efford, Labour MP for the London constituency of Eltham, was a cab driver for 10 years before entering parliament in 1997.

Private users

Oil millionaire Nubar Gulbenkian owned an Austin FX3 Brougham Sedanca taxi, with custom coachwork by FLM Panelcraft Ltd as he was quoted "because it turns on a sixpence whatever that is."[39] Gulbenkian had two such taxis built, the second of which was built on an FX4 chassis and was sold at auction by Bonhams for $39,600 in 2015.[40] Other celebrities are known to have used hackney carriages both for their anonymity and their ruggedness and manoeuvrability in London traffic. Users included Prince Philip, whose cab was converted to run on liquefied petroleum gas,[41] author and actor Stephen Fry,[42] and the Sheriffs of the City of London. A black cab was used in the band Oasis's video for the song "Don't Look Back in Anger." Black cabs were used as recording studios for indie band performances and other performances in the Black Cab Sessions internet project.

Ghosthunting With... featured a black cab owned by host of the show, Yvette Fielding. Bez of the Happy Mondays owns one, shown on the UK edition of Pimp My Ride. Noel Edmonds used a black cab to commute from his home to the Deal or No Deal studios in Bristol. He placed a dressed mannequin in the back so that he could use special bus/taxi lanes, and so that people would not attempt to hail his cab.[43]

The official car of the Governor of the Falkland Islands between 1976 and 2010 was a London taxi.[44]

In other countries

Between 2003 and 1 August 2009 the London taxi model TXII could be purchased in the United States. Today there are approximately 250 TXIIs in the US, operating as taxis in San Francisco, Dallas, Long Beach, Houston, New Orleans, Las Vegas, Newport, Rhode Island, Wilmington, North Carolina and Portland, Oregon. There are also a few operating in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The largest London taxi rental fleet in North America is in Wilmington, owned by The British Taxi Company. There are London cabs in Saudi Arabia, Romania, South Africa, Lebanon, Egypt, Bahrain and Cyprus, and in Israel, where a Chinese-made version of LTI's model TX4 built by Geely Automobile is available. In February 2010, a number of TX4s started operating in Pristina, the capital of Kosovo, and are known as London Taxi.[45]

Singapore has used London-style cabs since 1992; starting with the "Fairway". The flag-down fares for the London Taxis are the same as for other taxis. SMRT Corporation, the sole operator, had by March 2013 replaced its fleet of 15 ageing multi-coloured (gold, pink, etc.) taxis with new white ones. They are the only wheelchair-accessible taxis in Singapore, and were brought back following an outcry after the removal of the service.

By 2011 a thousand of a Chinese-made version of LTI's latest model, TX4, had been ordered by Baku Taxi Company. The plan is part of a program originally announced by Azerbaijan's Ministry of Transportation to introduce London cabs to the capital, Baku.[46][47] The move was part of a £16 million agreement between the London Taxi Company and Baku Taxi Company.[48][49]

Although the LEVC TX is more expensive and exceeds the Japanese size classifications to gain the tax advantages Japanese livery drivers enjoy with the similarly designed but smaller Toyota JPN Taxi, Geely has attempted to break into the Japanese market.[50] Alternatively, while the Toyota JPN Taxi doesn't meet the passenger capacity or turning radius Conditions of Fitness required by Transport for London, it does meet the emissions and accessibility requirements that may make it an ideal option for cities outside of London without the seating requirements or as a private hire vehicle while still evoking the familiar black cab profile.[51]

Variety of models

There have been different makes and types of hackney cab through the years,[52] including:

- Mann & Overton - including Carbodies, The London Taxi Company and currently London EV Company

- Unic sold in London from 1906 to 1930s

- Austin London Taxicab

- Austin FX3

- Austin/Carbodies/LTI FX4 and Fairway

- LTI TX1, TXII and TX4

- LEVC TX (plug-in hybrid range-extender)

- Mercedes-Benz

- Morris

- London General Cab Co.

- Beardmore

- Metrocab (originally formed by Metro Cammell Weymann)

- Dynamo Motor Company

- Dynamo Taxi(Nissan NV200 based)

Use in advertising

An example of an Eyetease digital screen on top of a hackney carriage

An example of an Eyetease digital screen on top of a hackney carriage Primelocation livery

Primelocation livery Vodafone livery

Vodafone livery Vita Coco livery

Vita Coco livery

The unique body of the London taxi is occasionally wrapped with all-over advertising, known as a "livery".

In October 2011 the company Eyetease Ltd. introduced digital screens on the roofs of London taxis for dynamically changing location-specific advertising.[54]

Future

On 14 December 2010, Mayor of London Boris Johnson released an air quality strategy paper encouraging phasing out of the oldest of the LT cabs, and proposing a £1m fund to encourage taxi owners to upgrade to low-emission vehicles. From 2018, all newly licensed taxis in London must be zero emission capable.[55]

In 2017, the LEVC TX was introduced - a purpose built hackney carriage, built as a plug-in hybrid range-extender electric vehicle.[56] By April 2022, over 5,000 TX's had been sold in London, around a third of London's taxi fleet.[57] In October 2019 the first fully electric cab since the Bersey in 1897, the Dynamo Taxi, was launched with a 187-mile range and with the bodywork based on Nissan's NV200 platform.[58][59]

Digital hailing

2011 saw the launch of many digital hailing applications for hackney carriages that operate through smartphones, including GetTaxi and Hailo. Many of these applications also facilitate payment and tracking of the taxicabs.

United Kingdom law

Laws about the definition, licensing and operation of hackney carriages have a long history.[60] The most significant pieces of legislation by region are:

- In England and Wales: the Town Police Clauses Act 1847, and the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976. In Wales, responsibility for licensing is now devolved to the National Assembly for Wales. In September 2017, a consultation started about the future of such licensing.

- In London: the Metropolitan Public Carriage Act 1869 and the London Cab Order 1934.

- In Scotland: the Civic Government (Scotland) Act 1982.

- In Northern Ireland: the Taxis Act (Northern Ireland) 2008[60]

See also

- Cabmen's Shelter Fund

- Cabvision

- Illegal taxicab operation

- M4 bus lane

- Toyota JPN Taxi

- VPG Standard Taxi

- Wagon

- Black Cab Rapist, a driver of a black cab

References

- "Fairway History". British Black Cab. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Transport Act 1985 - Legislation.gov.uk

- "London Taxi History". LVTA. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Absolon, John (1940). "Taxi". WW2 People's War. Sough, East England: BBC. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Definition of "hackney"". Onlinedictionary.datasegment.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Definition of remise by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "We know where we're going: London's women black cab drivers". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

Black cabs are synonymous with Britain; as strong a symbol of the London traffic-scape as red double-decker buses.

- "London taxis, black cabs and minicabs". Visit London. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- "Where to, Guv?", London Assembly Transport Committee report into the Public Carriage Office, November 2005

- "Boston Police Hackney Carriage Unit". Cityofboston.gov. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- 'Oxford English Dictionary' online pay site accessed 18 April 2018

- "jaca". Diccionario de la lengua española. Real Academia Española. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Dowell, Stephen (1884). A History of Taxes and Taxation in England: volume III. London: Longmans, Green & co. pp. 40–45.

- An Ordinance for the Regulation of Hackney-Coachmen in London and the places adjacent, June 1654, british-history.ac.uk; accessed 26 May 2017.

- "William and Mary, 1694: An Act for the lycenseing and regulateing Hackney-Coaches and Stage-Coaches [Chapter XXII Rot. Parl. pt. 5. nu. 2.]". Statutes of the Realm: Volume 6, 1685-94. Great Britain Record Commission. 1819. pp. 502–505. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "The Omnibuses of London". The Gentleman's Magazine. R. Newton: 663. December 1857.

- McCausland, Hugh (1948). The English Carriage. London: Batchworth Press.

- Knox, Thomas Wallace (1888) The pocket guide for Europe: hand-book for travellers on the Continent and the British Isles, and through Egypt, Palestine, and northern Africa G. Putnam, New York, page 34, OCLC 28649833

- Busch, Noel F. (1947) "Life's Reports: Restful Days in Dublin" " Life Magazine 15 September 1947 page 9, includes a photograph of a growler.

- "Taxi History - London Vintage Taxi Association". lvta.co.uk. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Lord Montagu of Beaulieu (5 June 1982). "London's Taxis". Autocar. Vol. 156, no. 4459. IPC Business Press Ltd. p. 42.

- Drozdz, Gregory (1990). Cab and Coach. p. 26. OCLC 841903541.

- "Cockington Carriages plan for the future - Cockington Court". www.cockingtoncourt.org.

- Golden times for black cabs, bbc.co.uk, 13 March 2002

- "London Wheelchair Taxis with Ramps". Wheelchair Travel. 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- "Why does traffic entering and leaving the Savoy Hotel in London drive on the right?". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Construction and Licensing of Motor Taxis for Use in London: Conditions of Fitness, as updated 17 September 2019" (PDF). Transport for London: Public Carriage Office. 17 September 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "London Taxis - Monday 16 January 1989 - Hansard - UK Parliament". hansard.parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- Mashburn, Rick (18 April 2004). "Rolling Along in London". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- "Taxicab History". London-Taxi. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

It was the first London cab to fully wheelchair accessible and to be licensed by the Public Carriage Office to carry four passengers.

- "Transported by Design". Archived from the original on 17 April 2016.

- London's transport ‘Design Icons’ announced Archived 31 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, ltmuseum.co.uk; accessed 26 May 2017.

- Transported By Design: Vote for your favourite part of London transport, timeout.com; accessed 26 May 2017.

- The history of London's black cabs, theguardian.com, 9 December 2012.

- About the Public Carriage Office, "Taxi and Private Hire Vehicle Statistics, England: 2018" (PDF). p. 2.

- Longest serving cabbie honoured, bbc.co.uk; accessed 26 May 2017.

- de Garis, Kirsty (9 February 2003). "What happened next?". The Observer. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Take our Mastermind quiz". BBC News. 7 July 2003. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- The sixpence was the smallest coin in circulation, so the phrase was a hyperbole meaning that it had a tight turning radius.

- "Bonhams The millionairee Paul Mellon wants to buy Gulbenkian's FX3, but Gulbenkian would not sell, but did allow Mellon to have replica built. This was also constructed by FLM Panelcraft, but on an FX4 chassis and was fitted with an American Ford 6-cylinder engine and automatic gearbox, as Mellon kept it in the USA: The ex-Nubar Gulbenkian,1960 AUSTIN FX4 BROUGHAM SEDANCA Chassis no. FX4AT033U010". www.bonhams.com.

- "Prince Philip's taxi". Royal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Stephen Fry in America, stephenfry.com, 10 October 2008.

- "Noel Edmonds dodged traffic by illegally driving a taxi in Bristol". motor1.com. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "Rex Hunt, Governor of the Falkland Islands". Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Ben-Gedalyahu, Dubi (18 August 2009). "Eldan to sell Chinese 'London taxi'". Globes. Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- Meidment, Neil. "Manganese Bronze seals biggest London taxi order". Reuters. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Jaglom, Ben. "Manganese takes black cab to Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "1,000 London taxis for Azerbaijan". Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "British firm wins £16m Azerbaijan order for its Chinese built taxis". Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Mihalascu, Dan (17 January 2020). "LEVC TX Electrified London Black Cab Lands In Japan, Targets Toyota's JPN Taxi". Carscoops.

- Richardson, Perry (29 January 2019). "The Toyota JPN Taxi: Changing the Asian landscape, can it change the UK's?". Taxi Point.

- "Taxicab Make And Model History". London-taxi.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012.

- "London Black-Cab Crisis Opens Road to Mercedes Minivans". Bloomberg. 3 December 2012.

- Mark Prigg (11 October 2011). "The video screen coming to a cab near you". ThisIsLondon. London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- "Emissions standards for taxis". Transport for London. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- "2,500th LEVC TX taxi rolls off production line". Auto Express. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- "LEVC CELEBRATES SALE OF 5000TH TX ELECTRIC TAXI IN LONDON". LEVC. 27 April 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- "Electric London black cab launches with 187-mile range | Autocar". www.autocar.co.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "First 100% electric black cab for 120 years launches in London". The Guardian. 23 October 2019.

- Butcher, Louise (2018). "Taxi and private hire vehicle licensing in England. House of Commons Briefing Paper CBP 2005" (PDF). Parliament. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

External links

- Fairway Owners Club and Forum

- Taxi fare calculator based on fares set by local authorities

- Taxis and private hire Transport for London Public Carriage Office

- London hackney coach regulations, 1819. Genealogy UK Genealogy and Family History.

- Roberts, Andy (22 November 2018). "20 Fascinating Facts About The Austin FX4". Lancaster Insurance.