English overseas possessions

The English overseas possessions, also known as the English colonial empire, comprised a variety of overseas territories that were colonised, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England during the centuries before the Acts of Union of 1707 between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland created the Kingdom of Great Britain. The many English possessions then became the foundation of the British Empire and its fast-growing naval and mercantile power, which until then had yet to overtake those of the Dutch Republic, the Kingdom of Portugal, and the Crown of Castile.

The first English overseas settlements were established in Ireland, followed by others in North America, Bermuda, and the West Indies, and by trading posts called "factories" in the East Indies, such as Bantam, and in the Indian subcontinent, beginning with Surat. In 1639, a series of English fortresses on the Indian coast was initiated with Fort St George. In 1661, the marriage of King Charles II to Catherine of Braganza brought him as part of her dowry new possessions which until then had been Portuguese, including Tangier in North Africa and Bombay in India.

In North America, Newfoundland and Virginia were the first centres of English colonisation. During the 17th century, Maine, Plymouth, New Hampshire, Salem, Massachusetts Bay, New Scotland, Connecticut, New Haven, Maryland, and Rhode Island and Providence were settled. In 1664, New Netherland and New Sweden were taken from the Dutch, becoming New York, New Jersey, and parts of Delaware and Pennsylvania.

Origins

The Kingdom of England is generally dated from the rule of Æthelstan from 927.[1] During the rule of the House of Knýtlinga, from 1013 to 1014 and 1016 to 1042, England was part of a personal union that included domains in Scandinavia. In 1066, William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, conquered England, making the Duchy a Crown land of the English throne. Through the remainder of the Middle Ages the kings of England held extensive territories in France, based on their history in this Duchy. Under the Angevin Empire, England formed part of a collection of lands in the British Isles and France held by the Plantagenet dynasty. The collapse of this dynasty led to the Hundred Years' War between England and France. At the outset of the war the Kings of England ruled almost all of France, but by the end of it in 1453 only the Pale of Calais remained to them.[2] Calais was eventually lost to the French in 1558. The Channel Islands, as the remnants of the Duchy of Normandy, retain their link to the Crown to the present day.

The first English overseas expansion occurred as early as 1169, when the Norman invasion of Ireland began to establish English possessions in Ireland, with thousands of English and Welsh settlers arriving in Ireland.[3] As a result of this the Lordship of Ireland was claimed for centuries by the English monarch; however, English control mostly was resigned to an area of Ireland known as The Pale, most of Ireland, large swaths of Munster, Ulster and Connaught remained free of English rule until the Tudor and Stuart period. It was not until the 16th century that the English began to colonize Ireland with protestant English settlers with the plantations of Ireland[4][5][6][7] One such overseas colony was the colony of King's County, now Offaly, and Queen's County, now Laois, in 1556.[8] A joint stock colony was planted in the late 1560s, at Kerrycurrihy near Cork city, on land leased from the Earl of Desmond.[9] Grenville also seized lands for colonization at Tracton, to the west of Cork harbour in 1569. In the early 17th century the Plantation of Ulster began.[10] English control of Ireland fluctuated for centuries until Ireland was incorporated into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.

The voyages of Christopher Columbus began in 1492, and he sighted land in the West Indies on 12 October that year. In 1496, excited by the successes in overseas exploration of the Portuguese and the Spanish, King Henry VII of England commissioned John Cabot to lead a voyage to find a route from the Atlantic to the Spice Islands of Asia, subsequently known as the search for the North West Passage. Cabot sailed in 1497, successfully making landfall on the coast of Newfoundland. There, he believed he had reached Asia and made no attempt to found a permanent colony.[11] He led another voyage to the Americas the following year, but nothing was heard of him or his ships again.[12]

The Reformation had made enemies of England and Spain, and in 1562 Elizabeth sanctioned the privateers Hawkins and Drake to attack Spanish ships off the coast of West Africa.[13] Later, as the Anglo-Spanish Wars intensified, Elizabeth approved further raids against Spanish ports in the Americas and against shipping returning to Europe with treasure from the New World.[14] Meanwhile, the influential writers Richard Hakluyt and John Dee were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own overseas empire. Spain was well established in the Americas, while Portugal had built up a network of trading posts and fortresses on the coasts of Africa, Brazil, and China, and the French had already begun to settle the Saint Lawrence River, which later became New France.[15]

The first English overseas colonies

The first English overseas colonies started in 1556 with the plantations of Ireland after the Tudor conquest of Ireland. One such overseas joint stock colony was established in the late 1560s, at Kerrycurrihy near Cork city[16] Several people who helped establish colonies in Ireland also later played a part in the early colonisation of North America, particularly a group known as the West Country men.[17]

The first English colonies overseas in America was made in the last quarter of the 16th century, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.[18] The 1580s saw the first attempt at permanent English settlements in North America, a generation before the Plantation of Ulster and occurring a little bit after the plantation of Munster. Soon there was an explosion of English colonial activity, driven by men seeking new land, by the pursuit of trade, and by the search for religious freedom. In the 17th century, the destination of most English people making a new life overseas was in the West Indies rather than in North America.

Early claims

Financed by the Muscovy Company, Martin Frobisher set sail on 7 June 1576, from Blackwall, London, seeking the North West Passage. In August 1576, he landed at Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island and this was marked by the first Church of England service recorded on North American soil. Frobisher returned to Frobisher Bay in 1577, taking possession of the south side of it in Queen Elizabeth's name. In a third voyage, in 1578, he reached the shores of Greenland and also made an unsuccessful attempt at founding a settlement in Frobisher Bay.[19][20] While on the coast of Greenland, he also claimed that for England.[21]

At the same time, between 1577 and 1580, Sir Francis Drake was circumnavigating the globe. He claimed Elizabeth Island off Cape Horn for his queen, and on 24 August 1578 claimed another Elizabeth Island, in the Straits of Magellan.[22] In 1579, he landed on the north coast of California, claiming the area for Elizabeth as "New Albion".[23] However, these claims were not followed up by settlements.[24]

In 1578, while Drake was away on his circumnavigation, Queen Elizabeth granted a patent for overseas exploration to his half-brother Humphrey Gilbert, and that year Gilbert sailed for the West Indies to engage in piracy and to establish a colony in North America. However, the expedition was abandoned before the Atlantic had been crossed. In 1583, Gilbert sailed to Newfoundland, where in a formal ceremony he took possession of the harbour of St John's together with all land within two hundred leagues to the north and south of it, although he left no settlers behind him. He did not survive the return journey to England.[25][26]

The first overseas settlements

arriving in Virginia, 1607

On 25 March 1584, Queen Elizabeth I granted Sir Walter Raleigh a charter for the colonization of an area of North America which was to be called, in her honour, Virginia. This charter specified that Raleigh had seven years in which to establish a settlement, or else lose his right to do so. Raleigh and Elizabeth intended that the venture should provide riches from the New World and a base from which to send privateers on raids against the treasure fleets of Spain. Raleigh himself never visited North America, although he led expeditions in 1595 and 1617 to the Orinoco River basin in South America in search of the golden city of El Dorado. Instead, he sent others to found the Roanoke Colony, later known as the "Lost Colony".[27]

On 31 December 1600, Elizabeth gave a charter to the East India Company, under the name "The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies".[28] The Company soon established its first trading post in the East Indies, at Bantam on the island of Java, and others, beginning with Surat, on the coasts of what are now India and Bangladesh.

Most of the new English colonies established in North America and the West Indies, whether successfully or otherwise, were proprietary colonies with Proprietors, appointed to found and govern settlements under Royal charters granted to individuals or to joint stock companies. Early examples of these are the Virginia Company, which created the first successful English overseas settlements at Jamestown in 1607 and Bermuda, unofficially in 1609 and officially in 1612, its spin-off, the Somers Isles Company, to which Bermuda (also known as the Somers Isles) was transferred in 1615, and the Newfoundland Company which settled Cuper's Cove near St John's, Newfoundland in 1610. Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts Bay, each incorporated during the early 1600s, were charter colonies, as was Virginia for a time. They were established through land patents issued by the Crown for specified tracts of land. In a few instances the charter specified that the colony's territory extended westward to the Pacific Ocean. The charter of Connecticut, Massachusetts Bay and Virginia each contained this "sea to sea" provision.

Bermuda, today the oldest-remaining British Overseas Territory, was settled and claimed by England as a result of the shipwreck there in 1609 of the Virginia Company's flagship Sea Venture. The town of St George's, founded in Bermuda in 1612, remains the oldest continuously-inhabited English settlement in the New World. Some historians state that with its formation predating the conversion of "James Fort" into "Jamestown" in 1619, St George's was actually the first successful town the English established in the New World. Bermuda and Bermudians have played important, sometimes pivotal, roles in the shaping of the English and British trans-Atlantic empires. These include roles in maritime commerce, settlement of the continent and of the West Indies, and the projection of naval power via the colony's privateers, among others.[29][30]

Between 1640 and 1660, the West Indies were the destination of more than two-thirds of English emigrants to the New World. By 1650, there were 44,000 English people in the Caribbean, compared to 12,000 on the Chesapeake and 23,000 in New England.[31] The most substantial English settlement in that period was at Barbados.

In 1660, King Charles II established the Royal African Company, essentially a trading company dealing in slaves, led by his brother James, Duke of York. In 1661, Charles's marriage to the Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza brought him the ports of Tangier in Africa and Bombay in India as part of her dowry. Tangier proved very expensive to hold and was abandoned in 1684.[32]

After the Dutch surrender of Fort Amsterdam to English control in 1664, England took over the Dutch colony of New Netherland, including New Amsterdam. Formalized in 1667, this contributed to the Second Anglo–Dutch War. In 1664, New Netherland was renamed the Province of New York. At the same time, the English also came to control the former New Sweden, in the present-day U.S. state of Delaware, which had also been a Dutch possession and later became part of Pennsylvania. In 1673, the Dutch regained New Netherland, but they gave it up again under the Treaty of Westminster of 1674.

Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations

In 1621, following a downturn in overseas trade which had created financial problems for the Exchequer, King James instructed his Privy Council to establish an ad hoc committee of inquiry to look into the causes of the decline. This was called The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of all matters relating to Trade and Foreign Plantations. Intended to be a temporary creation, the committee, later called a 'Council', became the origin of the Board of Trade which has had an almost continuous existence since 1621. The Committee quickly took a hand in promoting the more profitable enterprises of the English possessions, and in particular the production of tobacco and sugar.[33]

The Americas

List of English possessions in North America

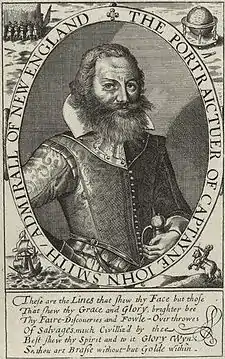

"Admiral of New England"

- St John's, Newfoundland, chartered in 1583 by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, was seasonally settled ca. 1520[34] and had settlers who remained all year round by 1620.[35][36]

- Roanoke Colony, in present-day North Carolina, was first founded in 1585 but was abandoned the next year. In 1587 a second attempt was made at establishing a settlement, but the colonists disappeared, leading to the name 'Lost Colony.' One of those lost was Virginia Dare.

- At Cuttyhunk, one of the Elizabeth Islands (named after Queen Elizabeth I) of present-day Massachusetts, a small fort and trading post was established by Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602, but the island was abandoned after only one month.

- The Virginia Company was chartered in 1606, and in 1624 its concessions became the royal Colony of Virginia.

- Jamestown, Virginia, was founded by the Virginia Company of London in 1607.

- Bermuda, also known as the Somers Isles, lying in the North Atlantic, were accidentally settled by the Virginia Company of London in 1609, due to the wrecking of the company's flagship Sea Venture; the company's possession was made official in 1612, when St George's, the oldest continually-inhabited, and the first proper, English town in the New World was established; in 1615 its administration passed to the Somers Isles Company, which was formed by the same shareholders; House of Assembly of Bermuda established in 1620; Bermudians' complaints to the Crown led to the revocation of the company's Royal charter in 1684.

- Henricus, also called Henricopolis, Henrico Town, and Henrico, was founded by the London Virginia Company in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy Jamestown, but it was largely destroyed in the Indian massacre of 1622.

- Popham Colony: on 13 August 1607, the Virginia Company of Plymouth settled the Popham Colony along the Kennebec River in present-day Maine. The company had a licence to establish settlements between the 38th parallel (the upper reaches of the Chesapeake Bay) and the 45th parallel (near the current US border with Canada). However, Popham was abandoned after about a year, and the Company then became inactive.

- The Society of Merchant Venturers of Bristol began to settle Newfoundland:

- Cuper's Cove, founded in 1610, was abandoned in the 1620s

- Bristol's Hope, founded in 1618, was abandoned in the 1630s

- London and Bristol Company (Newfoundland)

- Cambriol, founded in 1617. In 1616 Sir William Vaughan (1575–1641) bought from the Newfoundland Company all that land on the Avalon Peninsula located south of a line drawn from Caplin Bay (now Calvert) to Placentia Bay. The colony had been abandoned by 1637.

- Renews, founded in 1615, abandoned in 1619[37]

- Plymouth Council for New England

- Plymouth Colony, founded 1620, merged with Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691

- Ferryland, Newfoundland, granted to George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore in 1620, first settlers in August 1621[38]

- Province of Maine, granted 1622, sold to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1677

- South Falkland, Newfoundland, founded 1623 by Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland

- Province of New Hampshire, later New Hampshire settled in 1623, see also New Hampshire Grants

- Cape Ann was an unsuccessful fishing colony settled in 1624 by the Dorchester Company.

- Salem Colony, settled in 1628, merged with the Massachusetts Bay Colony the next year

- Massachusetts Bay Colony, later part of Massachusetts, founded in 1629

- New Scotland, in present Nova Scotia, 1629–1632

- Connecticut Colony, later part of Connecticut, founded in 1633

- Province of Maryland, later Maryland, founded in 1634

- Province of New Albion, chartered in 1634, but had failed by 1649–50.

- Saybrook Colony, founded in 1635, merged with Connecticut in 1644

- Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, first settled in 1636

- New Haven Colony, founded 1638, merged with Connecticut in 1665

- Gardiners Island, founded 1639, now part of East Hampton, New York

- The New England Confederation, formally the 'United Colonies of New England', was a short-lived military alliance of the English colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven, established in 1643, aiming to unite the Puritan colonies against the Native Americans. Its charter provided for the return of fugitive criminals and indentured servants.[39]

- Province of New York, captured from the Dutch in 1664

- Province of New Jersey, also captured in 1664

- Was divided into West Jersey and East Jersey after 1674, each held by its own company of Proprietors.

- Rupert's Land, named in honour of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the cousin of King Charles II. In 1668, Rupert commissioned two ships, the Nonsuch and the Eaglet, to explore possible trade into Hudson Bay. Nonsuch founded Fort Rupert at the mouth of the Rupert River. Prince Rupert became the first governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, which was established in 1670.

- Province of Pennsylvania, later Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 as an English colony, although first settled by the Dutch and the Swedes

- Delaware Colony, later Delaware, separated from Pennsylvania in 1704

- Province of Carolina, settled 1653 at the Albemarle Settlements, chartered 1663 as a single territory but soon functioning in practice as two separate colonies:

- Province of North Carolina, later North Carolina; first settled at Roanoke in 1586, permanently settled 1653, became a separate British colony in 1710.

- Province of South Carolina, later South Carolina; first permanently settled in 1670, became a separate British colony in 1710.

- One possession established after 1707 as a British colony rather than English:

- Province of Georgia, later Georgia; first settled in 1732.

List of English possessions in the West Indies

- Barbados, first visited by an English ship, the Olive Blossom, in 1605,[40] was not settled by England until 1625,[41] soon becoming the third major English settlement in the Americas after Jamestown, Virginia, and the Plymouth Colony.

- Saint Kitts was settled by the English in 1623, followed by the French in 1625. The English and French united to massacre the local Kalinago, pre-empting a Kalinago plan to massacre the Europeans, and then partitioned the island, with the English in the middle and the French at either end. In 1629 a Spanish force seized St Kitts, but the English settlement was rebuilt following the peace between England and Spain in 1630. The island then alternated between English and French control during the 17th and 18th centuries until it became permanently associated with Britain since 1783.

- Nevis, settled 1628

- Providence Island colony, settled by the Providence Island Company in 1629 and captured by Spain in 1641.

- Montserrat, settled 1632

- Antigua, settled in 1632 by a group of English colonists from Saint Kitts

- The Bahamas were mostly deserted from 1513 to 1648, when the Eleutheran Adventurers left Bermuda to settle on the island of Eleuthera.

- Anguilla, first colonized by English settlers from St Kitts in 1650; the French gained the island in 1666, but under the Treaty of Breda of 1667 it was returned to England

- Jamaica, formerly a Spanish possession known as Santiago, it was conquered by the English in 1655.

- Barbuda, first settled by the Spanish and French, was colonized by the English in 1666.

- The Cayman Islands were visited by Sir Francis Drake in 1586, who named them. They were largely uninhabited until the 17th century, when they were informally settled by pirates, refugees from the Spanish Inquisition, shipwrecked sailors, and deserters from Oliver Cromwell's army in Jamaica. England gained control of the islands, together with Jamaica, under the Treaty of Madrid of 1670.

List of English possessions in Central and South America

- Elizabeth Island off Cape Horn, and another Elizabeth Island in the Straits of Magellan, were claimed for England by Sir Francis Drake in August 1578.[22] However, no settlements were made and it is no longer possible to identify the islands with certainty.

- Guiana: an attempt in 1604 to establish a colony failed in its main objective to find gold and lasted only two years.[42]

- Mosquito Coast: the Providence Island Company occupied a small part of this area in the 17th century.

- Falkland Islands: Claimed for England by mariner John Strong in 1690, who made the first recorded landing on the islands.

English possessions in India and the East Indies

- Bantam: The English started to sail to the East Indies about the year 1600, which was the date of the foundation in the City of London of the East India Company ("the Governour and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies") and in 1602 a permanent "factory" was established at Bantam on the island of Java.[43] At first, the factory was headed by a Chief Factor, from 1617 by a President, from 1630 by Agents, and from 1634 to 1652 by Presidents again. The factory then declined.

- Surat: The East India Company's traders settled at Surat in 1608, followed by the Dutch in 1617. Surat was the first headquarters town of the East India Company, but in 1687 it transferred its command centre to Bombay.

- Machilipatnam: a trading factory was established here on the Coromandel Coast of India in 1611, at first reporting to Bantam.[44]

- Run, a spice island in the East Indies. On 25 December 1616, Nathaniel Courthope landed on Run to defend it against the claims of the Dutch East India Company and the inhabitants accepted James I as sovereign of the island. After four years of siege by the Dutch and the death of Courthope in 1620, the English left. According to the Treaty of Westminster of 1654, Run should have been returned to England, but was not. After the Second Anglo-Dutch War, England and the United Provinces agreed to the status quo, under which the English kept Manhattan, which the Duke of York had occupied in 1664, while in return Run was formally abandoned to the Dutch. In 1665 the English traders were expelled.

- Fort St George, at Madras (Chennai), was the first English fortress in India, founded in 1639. George Town was the accompanying civilian settlement.

- Bombay: On 11 May 1661, the marriage treaty of King Charles II and Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal, transferred Bombay into the possession of England, as part of Catherine's dowry.[45] However, the Portuguese kept several neighbouring islands. Between 1665 and 1666, the English acquired Mahim, Sion, Dharavi, and Wadala.[46] These islands were leased to the East India Company in 1668. The population quickly rose from 10,000 in 1661, to 60,000 in 1675.[47] In 1687, the East India Company transferred its headquarters from Surat to Bombay, and the city eventually became the headquarters of the Bombay Presidency.[48]

- Bencoolen was an East India Company pepper-trading centre with a garrison on the coast of the island of Sumatra, established in 1685.

- Calcutta on the Hooghly River in Bengal was settled by the East India Company in 1690.

English possessions in Africa

.jpg.webp)

- The Gambia River: in 1588, António, Prior of Crato, claimant to the Portuguese throne, sold exclusive trade rights on the Gambia River to English merchants, and Queen Elizabeth I confirmed his grant by letters patent. In 1618, King James I granted a charter to an English company for trade with the Gambia and the Gold Coast. The English captured Fort Gambia from the Dutch in 1661, who ceded it in 1664. The island on which the Fort stood was renamed James Island, and the fort Fort James, after James, Duke of York, later King James II. At first the chartered Company of Royal Adventurers in Africa administered the territory, which traded in gold, ivory, and slaves. In 1684, the Royal African Company took over the administration.

- English Tangier: this was another English possession gained by King Charles II in 1661 as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza. While it was strategically important, Tangier proved very expensive to garrison and defend and was abandoned in 1684.[32]

- Saint Helena, an island in the South Atlantic, was settled by the English East India Company in 1659 under a charter of Oliver Cromwell granted in 1657. (The associated islands of Ascension and Tristan da Cunha were not settled until the 19th century.)

English possessions in Europe

- Duchy of Normandy: Normandy became associated with the English crown in 1066 when the Duke of Normandy William the Conqueror became King of England. The mainland duchy was conquered by Philip II of France in 1204 and English claims finally relinquished in the Treaty of Paris in 1259. The Channel Islands remained English.

- County of Anjou and County of Maine: Anjou and Maine merged with the English crown when the Count of Anjou became Henry II of England in 1154. They were lost to the French in 1204.

- Duchy of Aquitaine: Aquitaine, a fief of the Kingdom of France, passed to the English through the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to the future Henry II of England in 1152. The duchy was declared forfeit by Philip VI of France in 1337, beginning the Hundred Years' War, but Edward III of England was recognised as sovereign Lord of Aquitaine by the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. The French reconquest of Aquitaine began in 1451 and was complete with the Battle of Castillon in 1453.

- Kingdom of France: Edward III of England first claimed the French throne in 1340 but abandoned it under the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. He resumed his claim in 1369 and Henry V of England was recognised as heir to the French throne by the Treaty of Troyes in 1420; his son Henry VI of England succeeded as de facto King of France in 1422. Between 1429 and 1453 the French drove the English out of France, and the Hundred Years' War was finally ended by the Treaty of Picquigny in 1475, when Edward IV of England agreed not to pursue his claim further. English and later British monarchs continued to use the title of King or Queen of France until 1801.

- Pale of Calais: Calais had been captured by Edward III in 1347 and English possession was confirmed by the Treaty of Brétigny. It was the only remaining English possession on the Continent after the effective end of the Hundred Years' War in 1453. Calais was recaptured by the French in 1558 and French occupation recognised by the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. English claims were finally abandoned by the Treaty of Troyes in 1564.

- Tournai: Tournai was occupied by Henry VIII of England following the Battle of the Spurs in 1513. It was returned to France in 1519 under the terms of the Treaty of London.

- Le Havre: English troops occupied Le Havre under the Treaty of Hampton Court in 1562. The town was reconquered by the French the following year.

- Cautionary Towns: English possession of Flushing and Brill was confirmed by the Treaty of Nonsuch in 1585. The towns were sold to the Dutch Republic in 1616.

- Dunkirk: French and English forces captured Dunkirk from the Spanish in 1658, and the town was granted to England by the Treaty of the Pyrenees the next year. Dunkirk was sold back to France in 1662.

- Gibraltar: In 1704, Gibraltar was captured for England by an Anglo-Dutch fleet, becoming the country's first European overseas possession since the sale of Dunkirk to France in 1662. The Naval operation was commanded by George Rooke. Gibraltar later became a strategic naval base for the Royal Navy and was officially ceded to Great Britain in 1713. It remains a British possession.

Transformation into British Empire

The Treaty of Union of 1706, which with effect from 1707 combined England and Scotland into a new sovereign state called Great Britain, provided for the subjects of the new state to "have full freedom and intercourse of trade and navigation to and from any port or place within the said united kingdom and the Dominions and Plantations thereunto belonging". While the Treaty of Union also provided for the winding up of the Scottish African and Indian Company, it made no such provision for the English companies or colonies. In effect, with the Union they became British colonies.[49]

List of English possessions which are still British Overseas Territories

North America and the West Indies

Africa

- The island of Saint Helena in Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

Europe

Timeline

- 1607 Jamestown, Virginia

- 1609 Bermuda

- 1612 Surat, India

- 1620 East coast of Newfoundland (island) and Plymouth, Massachusetts

- 1625 Barbados and Saint Kitts, Caribbean

- 1628 Nevis

- 1630 Boston, North America and Mosquito Coast, Central America

- 1632 Antigua and Montserrat, Caribbean

- 1638 Belize (British Honduras)

- 1639 Chennai (Madras), India

- 1648 The Bahamas

- 1650 Anguilla

- 1660 Jamaica and Cayman Islands, Caribbean

- 1661 Mumbai, India and Dog Island, Gambia

- 1663 Saint Lucia

- 1664 New Netherland, North America

- 1666 Barbuda

- 1670 Turks and Caicos Islands and Rupert's Land

- 1672 British Virgin Islands

- 1673 Fort James, Ghana

- 1682 Philadelphia

- 1690 Kolkata (Calcutta), India

- 1704 Gibraltar

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- Keynes, Simon. "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons" in N. J. Higham & D. H. Hill, Edward the Elder 899-924 (London: Routledge, 2001), p. 61.

- Griffiths, Ralph A. King and Country: England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century (2003, ISBN 1852850183), p. 53

- Bartlett, Thomas. Ireland: A History (2010, ISBN 0521197201) p. 40.

- Falkiner, Caesar Litton (1904). Illustrations of Irish history and topography, mainly of the 17th century. London: Longmans, Green, & Co. p. 117. ISBN 1-144-76601-X.

- Moody, T. W.; Martin, F. X., eds. (1967). The Course of Irish History. Cork: Mercier Press. p. 370.

- Ranelagh, John (1994). A Short History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 36.

- Ruth Dudley Edwards; Bridget Hourican (2005). An Atlas of Irish History. Psychology Press. pp. 33–34.

- 3 & 4 Phil & Mar, c.2 (1556). The Act was repealed in 1962 Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland, the Incomplete Conquest, pp. 211–213

- Hill, George. The Fall of Irish Chiefs and Clans and the Plantation of Ulster (2004, ISBN 094013442X)

- Kenneth Andrews, Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630 (Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-521-27698-5) p. 45.

- Ferguson, Niall. Colossus: The Price of America's Empire (Penguin, 2004, p. 4)

- Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade: the History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (Picador, 1997), pp. 155–158.

- Ferguson (2004), p. 7.

- Lloyd, Trevor Owen. The British Empire 1558–1995 (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-873134-5), pp. 4–8.

- Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland, the Incomplete Conquest, pp. 211–213

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies, The Settling of North America. Penguin. pp. 119, 123. ISBN 0-14-200210-0.

- Nicholas Canny, The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire, vol. I (Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-924676-9), p. 35

- The Nunavut Voyages of Martin Frobisher at web site of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, accessed 5 August 2011

- Cooke, Alan (1979) [1966]. "Frobisher, Sir Martin". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- McDermott, James. Martin Frobisher: Elizabethan privateer (Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-300-08380-7.) p. 190

- Francis Fletcher, The World encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (1854 edition) by the Hakluyt Society, p. 75.

- Dell'Osso, John (October 12, 2016). "Drakes Bay National Historic Landmark Dedication". NPS.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Sugden, John. Sir Francis Drake (Barrie & Jenkins, 1990, ISBN 0-7126-2038-9), p. 118.

- Andrews (1984), pp. 188-189

- Quinn, David B. (1979) [1966]. "Gilbert, Sir Humphrey". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- David B. Quinn, Set fair for Roanoke: voyages and colonies, 1584–1606 (1985)

- The register of letters, &c: of the governour and company of merchants of London trading into the East Indies, 1600–1619 (B. Quaritch, 1893), p. 3.

- Delgado, Sally J. (2015). "Reviewed Work: In the Eye of All Trade by Michael J. Jarvis". Caribbean Studies. 43 (2): 296–299. doi:10.1353/crb.2015.0030. ISBN 978-0-8078-3321-6. S2CID 152211704. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- Lt. Col. Gavin Shorto, The Bermudian: Bermuda in the Privateering Business Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Alan Taylor, Colonial America: A Very Short Introduction (2012), p. 78

- John Wreglesworth, Tangier: England's Forgotten Colony (1661-1684), p. 6

- Encyclopædia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge (Volume 10, 1963), p. 583

- Nicholas Canny, The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume I, 2001, ISBN 0-19-924676-9.

- "Early Settlement Schemes". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site Project. Memorial University of Newfoundland. 1998. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- Paul O'Neill, The Oldest City: The Story of St. John's, Newfoundland, 2003, ISBN 0-9730271-2-6.

- "William Vaughan and New Cambriol". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site Project. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- Permanent Settlement at Avalon, Colony of Avalon Foundation, Revised March 2002, accessed 6 August 2011

- John Andrew Doyle, English Colonies in America: The Puritan colonies (1889) chapter 8, p. 220

- Sir Robert Schomburg, History of Barbados (2012 edition), p. 258

- Reuben Gold Thwaites, The Colonies, 1492-1750 (1927), p. 245

- Canny, p. 71

- East India Company, The Register of Letters &c. of the Governour and Company of Merchants of London Trading Into the East Indies, 1600-1619 (B. Quaritch, 1893), pp. lxxiv, 33

- N. S. Ramaswami, Fort St. George, Madras (Madras, 1980; Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology, No. 49)

- "Catherine of Bragança (1638–1705)". BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island (1978) p. 54

- M. D. David, History of Bombay, 1661–1708 (1973) p. 410

- F. L. Carsten, The New Cambridge Modern History V (The ascendancy of France 1648–88) (Cambridge University Press, 1961, ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5), p. 427

- Treaty of Union of the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England at scotshistoryonline.co.uk, accessed 2 August 2011

Sources

- Primary sources

- Crouch, Nathaniel. The English Empire in America: or a Prospect of His Majesties Dominions in the West-Indies (London, 1685).

Further reading

- Adams, James Truslow, The Founding of New England (1921), to 1690

- Andrews, Charles M., The Colonial Period of American History (4 vols. 1934–38), the standard political overview to 1700

- Andrews, Charles M., Colonial Self-Government, 1652–1689 (1904) full text online

- Bayly, C. A., ed., Atlas of the British Empire (1989), survey by scholars, heavily illustrated

- Black, Jeremy, The British Seaborne Empire (2004)

- Coelho, Philip R. P., "The Profitability of Imperialism: The British Experience in the West Indies 1768–1772", Explorations in Economic History, July 1973, Vol. 10 Issue 3, pp. 253–280.

- Dalziel, Nigel, The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire (2006), 144 pp

- Doyle, John Andrew, English Colonies in America: Virginia, Maryland and the Carolinas (1882) online edition

- Doyle, John Andrew, English Colonies in America: The Puritan colonies (1889) online edition

- Doyle, John Andrew, The English in America: The colonies under the House of Hanover (1907) online edition

- Ferguson, Niall, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (2002)

- Fishkin, Rebecca Love, English Colonies in America (2008)

- Foley, Arthur, The Early English Colonies (Sadler Phillips, 2010)

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 vol 1936–70), comprehensive scholarly overview

- Morris, Richard B., "The Spacious Empire of Lawrence Henry Gipson", William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 24, No. 2 (Apr., 1967), pp. 169–189 in JSTOR

- Green, William A., "Caribbean Historiography, 1600–1900: The Recent Tide", Journal of Interdisciplinary History Vol. 7, No. 3 (Winter, 1977), pp. 509–530. in JSTOR

- Greene, Jack P., Peripheries & Center: Constitutional Development in the Extended Polities of the British Empire & the United States, 1607–1788 (1986), 274 pages.

- James, Lawrence, The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997)

- Jernegan, Marcus Wilson, The American Colonies, 1492–1750 (1959)

- Koot, Christian J., Empire at the Periphery: British Colonists, Anglo-Dutch Trade, and the Development of the British Atlantic, 1621–1713 (2011)

- Knorr, Klaus E., British Colonial Theories 1570–1850 (1944)

- Louis, William, Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire, 5 vols (1998–99), vol. 1 "The Origins of Empire" ed. Nicholas Canny (1998)

- McDermott, James, Martin Frobisher: Elizabethan privateer (Yale University Press, 2001).

- Marshall, P. J., ed., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996)

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson, Empire Divided: The American Revolution & the British Caribbean (2000) 357pp

- Parker, Lewis K., English Colonies in the Americas (2003)

- Payne, Edward John, Voyages of the Elizabethan Seamen to America (vol. 1, 1893; vol. 2, 1900)

- Payne, Edward John, History of the New World called America (vol. 1, 1892; vol. 2, 1899)

- Quinn, David B., Set Fair for Roanoke: voyages and colonies, 1584–1606 (1985)

- Rose, J. Holland, A. P. Newton and E. A. Benians, gen. eds., The Cambridge History of the British Empire, 9 vols (1929–61); vol 1: "The Old Empire from the Beginnings to 1783" (online edition)

- Sheridan, Richard B., "The Plantation Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, 1625–1775", Caribbean Studies Vol. 9, No. 3 (Oct., 1969), pp. 5–25. in JSTOR

- Sitwell, Sidney Mary, Growth of the English Colonies (new ed. 2010)

- Thomas, Robert Paul, "The Sugar Colonies of the Old Empire: Profit or Loss for Great Britain" in Economic History Review April 1968, Vol. 21 Issue 1, pp. 30–45.

.jpg.webp)