French protectorate of Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia (French: Protectorat français de Tunisie; Arabic: الحماية الفرنسية في تونس al-Ḥimāya al-Fransīya fī Tūnis), commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial Empire era, and lasted until Tunisian independence in 1956.

French protectorate of Tunisia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1881–1956 | |||||||||

| Anthem: | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Protectorate | ||||||||

| Capital | Tunis | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Tunisian | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy under French protection | ||||||||

| Bey | |||||||||

• 1859–1882 (first) | Muhammad III | ||||||||

• 1943–1956 (last) | Muhammad VIII | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1881–1882 (first) | Mohamed Khaznadar | ||||||||

• 1954–1956 (last) | Tahar Ben Ammar | ||||||||

| Resident-General | |||||||||

• 1885–1886 (first) | Paul Cambon | ||||||||

• 1955–1956 (last) | Roger Seydoux[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

| 12 May 1881 | |||||||||

| 20 March 1956 | |||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Tunisia | ||||||||

The protectorate was established by the Bardo Treaty of 12 May 1881 after a military conquest,[1] despite Italian disapproval.[2] It was part of French North Africa with French Algeria and the Protectorate of Morocco, and more broadly of the French Empire.[3] Tunisian sovereignty was more reduced in 1883, the Bey was only signing the decrees and laws prepared by the Resident General of France in Tunisia. The Tunisian government at the local level remained in place, and was only coordinating between Tunisians and the administrations set up on the model of what existed in France. The Tunisian government's budget was quickly cleaned up, which made it possible to launch multiple infrastructure construction programs (roads, railways, ports, lighthouses, schools, hospitals, etc.) and the reforms that took place during the Beylik era contributed to this,[4] which completely transformed the country above all for the benefit of the settlers, mostly Italians whose numbers were growing rapidly. A whole land legislation was put in place allowing the acquisition or the confiscation of land in order to create lots of colonization resold to the French colonists.

The first nationalist party, Destour, was created in 1920, but its political activity decreased rapidly in 1922. However, Tunisians educated in French universities revived the nationalist movement. A new party, the Neo Destour, was created in 1934 whose methods quickly showed their effectiveness. Police repression only accentuated the mobilization of the Tunisian people. The occupation of the country in 1942 by Germany and the deposition of Moncef Bey in 1943 by the French authorities reinforced the exasperation of the population. After three years of guerrilla, internal autonomy was granted in 1955. The protectorate was finally abolished on 20 March 1956.

Context

Background

In 1859, Tunisia was ruled by the Bey Muhammad III, and the powerful Prime Minister, Mustapha Khaznadar, who according to Wesseling "had been pulling the strings ever since 1837."[5] Khaznadar was minister of finance and foreign affairs and was assisted by the interior, defence, and naval ministers. In 1861, Tunisia was granted a constitution with a clear division of ministerial powers and responsibilities, but in practice, Khaznadar was the absolute sovereign.[5] He pursued reformist policies promoting economic development, specifically aimed at improving, infrastructure, communication, and the armed forces. The Tunisian economy did not, however, generate enough revenue to sustain these reforms.[4] Central administration, additionally, was weak. Tax collection was devolved onto tax-farmers, and only one-fifth of the revenues ever reached the national treasury. Many hill tribes and desert nomads lived in quasi-independence. Economic conditions deteriorated through the 19th century, as foreign fleets curbed corsairs, and droughts perennially wreaked havoc on production of cereals and olives. Because of accords with foreign traders dating back to the 16th century, custom duties were limited to 3 per cent of the value of imported goods; yet manufactured products from overseas, primarily textiles, flooded Tunisia and gradually destroyed local artisan industries.

In 1861, Prime Minister Mustapha Khaznadar made an effort to modernise administration and increase revenues by doubling taxes. The primary effect, only fully felt by 1864, was widespread rural insurrection, coupled with great hardship for the general population. The government had to negotiate a new loan from foreign bankers. In 1867, an attempt to secure money failed; government revenues were insufficient to meet annual interest payments on the national debt. Tunisia plunged towards bankruptcy. Two years later France, Italy and Britain set up an international finance commission to sort out Tunisia's economic problems and safeguard Western interests. Their actions enjoyed only partial success, largely because of opposition from foreign traders to increases in customs levies. In 1873, Khaznadar again undertook reforms and attacked the widespread financial abuses within the bureaucracy. The results were initially promising, but bad harvests and palace intrigue led to his downfall.

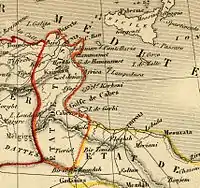

The Bey reigned over Tunisia, whose southern borders were ill-defined against the Sahara.[5] To the east lay Tripolitania, province of the Ottoman Empire, which had made itself practically independent until Sultan Mahmud II successfully restored his authority by force in 1835.[5] The Bey of Tunisia became worried of the strengthening of Ottoman authority in the east, and was therefore not too unhappy in 1830 when another country, France, had settled on his western borders. According to Wesseling, the bey considered the conquest of his country by the Porte would be worse than a possible conquest by France.[5]

At the time, Tunisia had just over a million inhabitants. Half of these were sedentary farmers who lived mainly in the northeast, and the other half were nomadic shepherds who roamed the interior. There were several towns, including Tunis with nearly 100,000 inhabitants, and Kairouan with 15,000, where traders and artisans were active, despite being severely affected by foreign competition. The traditional Tunisian textile industry couldn't compete with imported goods from industrialized Europe. The financial world was dominated by Tunisian Jews, while a growing number of Europeans, almost exclusively Italians and Maltese, settled in Tunisia. In 1870, there were 15,000 of them.[6] The economic situation of Tunisian townsmen may accordingly have been under pressure, but it was flourishing in comparison with that of the fellahin, peasants who laboured under a whole series of taxes and requisitions. From 1867 to 1868, crop failure, subsequent famine, and epidemics of cholera and typhus combined to kill some 20 percent of the population.[5]

These circumstances made the Tunisian government unable, despite all levies and demands, to collect the tax revenues they deemed necessary to modernise Tunisia.

Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin, held in 1878, convened to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia.

At the Congress arrangements were also understood, e.g., by Germany and Britain, wherein France would be allowed to incorporate Tunisia. Italy was promised Tripolitania in what became Libya. Britain supported French influence in Tunisia in exchange for its own protectorate over Cyprus (recently "purchased" from the Ottomans), and French cooperation regarding a nationalist revolt in Egypt.

In the meantime, however, an Italian company apparently bought the Tunis-Goulette-Marsa rail line; yet French strategy worked to circumvent this and other issues created by the sizable colony of Tunisian Italians. Direct attempts by the French to negotiate with the Bey their entry into Tunisia failed. France waited, searching to find reasons to justify the timing of a preemptive strike, now actively contemplated. Italians would call such strike the Schiaffo di Tunisi.[7]

Slap of Tunis

Italy had a strong interest in Tunisia since at least the early 19th century, and had briefly entertained the idea of invading the country in the 1860s.[8] Italian was the lingua franca of Tunisian diplomacy well into the 19th century, and of the various expatriate communities in Tunis that did not speak Arabic.[9]

For this reason, the first foreign policy objective of Benedetto Cairoli's government was the colonisation of Tunisia, to which both France and Italy aspired. Cairoli, like Agostino Depretis before him, never considered to proceed to occupation, being generally hostile towards a militarist policy.[10] However, they relied on a possible British opposition to an enlargement of the French sphere of influence in North Africa (while, if anything, London was hostile about a single country controlling the whole Strait of Sicily).[11]

In the beginning of 1881 France decided to militarily intervene in Tunisia. The motivations of this action were provided by Jules Ferry, who sustained that the Italians wouldn't have opposed it because some weeks before France had consented to a renewal of the Italo-French trade treaty, Italy was still paying debts contracted with France and primarily it was Italy that was politically isolated despite its tentatives towards the German Empire and Austria-Hungary (Ferry confirmed that it was Otto von Bismarck to invite Paris to act in Tunisia precising that, in case of action, Germany wouldn't have raised objections.[12] While in Italy there was a debate about the reliability of the news about a possible French action in Tunisia, a twenty-thousand-men expeditionary corps was preparing in the Toulon arsenal. On 3 May a French contingent of two thousand men landed in Bizerte, followed on 11 May by the rest of the forces.[13] The episode gave an ulterior confirm of the Italian political isolation, and rekindled the polemics that had followed the Congress of Berlin three years before. The events, in effect, demonstrated the irrealisability of the foreign policy of Cairoli and of Depretis, the impossibility of an alliance with France and the necessity of a rapprochement with Berlin and with Vienna, even if obtorto collo.

However, such an inversion of the foreign policy of the last decade couldn't be led by the same men, and Benedetto Cairoli resigned from office on 29 May 1881, thus avoiding that the Camera would openly distrust him; since then he de facto disappeared from the political scene. The Italians called these events The Schiaffo di Tunisi (literally Slap of Tunis).

After the establishment of French protectorate, Italian immigrants in Tunisia would have protested and caused serious difficulties to France. However, little at a time, the problem was solved and the immigrants could later opt for French nationality and benefit from the same vantages as French colonists. Italo-French relation dangerously fractured. Among the hypotheses weighed by the Italian military staff a possible invasion of the Italian Peninsula by French troops was not excluded.[14]

Conquest

First Campaign

Taking the pretext of border incidents between the Algerian tribe of Ouled Nahd and the Tunisian tribe of Kroumirs on 30 and 31 March 1881, the French government led by Jules Ferry decided to send a force of 24,000 soldiers placed under the command of General Léonard-Léopold Forgemol de Bostquénard on the border between Tunisia and French Algeria.

On 24 April 1881, French troops entered Tunisia from the north (Tabarka), the center of Kroumirie and Sakiet Sidi Youssef.[15] Tabarka was invaded on 26 April,[16] as well as Le Kef on the same day. The three armies can then join together to eliminate the mountain tribes who resisted until 26 May.[17]

Encouraged by the inertia of the Tunisian army, which had not moved to defend the town of Le Kef against the French attack, Jules Ferry decided to send a force of 6,000 soldiers under the command of General Jules Aimé Bréart to land at Bizerte from 1 May 1881. The city had no resistance and on 8 May 8, the military force took the road to Tunis. On May 12, the French soldiers encamped at La Manouba, not far from the Bardo Palace.

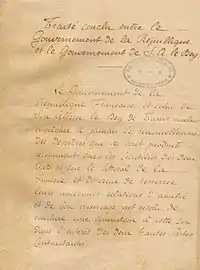

Bardo Treaty

At 4 p.m., escorted by two squadrons of hussars, Bréart presented himself in front of the Bey's palace accompanied by his entire staff and most of the senior military officers. Tunisian soldiers honored them. They are introduced into the living room where Sadok Bey and the French consul Théodore Roustan are waiting for them. Fearing being deposed and replaced by his brother Taïeb Bey, the monarch signed the treaty at 7:11 p.m. However, he managed to prevent the French troops from entering the capital.[18]

By this text, France deprived the Tunisian State of the right of active legation by entrusting diplomatic and consular agents of France in foreign countries with the protection of Tunisian interests and nationals of the Beylik. As for the Bey, he can no longer conclude any act of an international nature without having first informed the French State and without having its permission. By this treaty, France also undertook to ensure the durability of the monarchical regime and to preserve the Bey's status as sovereign and head of state; article 3 indicated that the Government of the French Republic undertakes to lend constant support to H.H the Bey of Tunis against any danger.

The last shots were fired on 26 May where 14 French soldiers and an unknown number of Tunisians died.[19]

Second Campaign

The return to France of half of the military force encouraged the country to take up arms. The signal for the revolt was given by Sfax on 27 June. The local authorities were overwhelmed and the Europeans have to evacuate the city in disaster. The rebellion was put down by marines from the Mediterranean squadron who retook the city on 16 July after four hours of street fighting, as well as Gabès on 30 July.

The whole country imitated the example of the Sfaxiens. In August, Kairouan was taken over by the rebels.

The Kef military camp was besieged by 5,000 fighters led by the chief of the Ouled Ayar tribe, Ali Ben Ammar. Near Hammamet, a French military force was harassed by 6,000 insurgents between 26 and 30 August and lost 30 soldiers. European civilians were not spared. On 30 September, the Oued Zarga station was attacked and nine employees were massacred. Following this massacre, Tunis was occupied on 7 October by French troops to reassure the foreign population.

Troops are sent as reinforcements from French Algeria. On 26 October, Kairouan was recaptured from the insurgents by the French forces. Ben Ammar's fighters were routed on 22 October; the last resisters were surrounded on 20 November. The last fighting stops at the end of December 1881.[20]

Occupation

In northwest Tunisia, the Khroumir tribe episodically launched raids into the surrounding countryside. In the spring of 1881, they raided across the border into French Algeria, attacking the Algerian Ouled-Nebed tribe. On 30 March 1881 French troops clashed with the raiders.[21] Using the pretext of droit de poursuite (right of pursuit) France responded by invading Tunisia, sending an army of about 36,000. Their advance to Tunis was rapidly executed, though tribal opposition in the far south and at Sfax continued until December.[22]

The Bey was soon compelled to come to terms with the French occupation of the country, signing the first of a series of treaties. These documents provided that the Bey continue as head of state, but with the French given effective control over a great deal of Tunisian governance, in the form of a protectorate.[23]

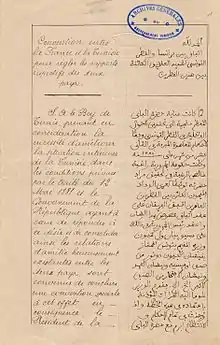

With her own substantial interests in Tunisia, Italy protested but would not risk a confrontation with France. Hence Tunisia officially became a French protectorate on May 12, 1881, when the ruling Sadik Bey (1859–1882) signed the Treaty of Bardo (Al Qasr as Sa'id). Later in 1883 his younger brother and successor 'Ali Bey signed the al-Marsa Convention.

French Protectorate (1881–1956)

France did not enlarge its Maghreb domain beyond Algeria for half a century. The next area for expansion, at the beginning of the 1880s, was Tunisia. With an area of 155,000 square kilometers, Tunisia was a small prize, but it occupied strategic importance, across the Algerian frontier and only 150 kilometers from Sicily; Tunisia offered good port facilities, especially at Bizerte. France and Italy, as well as Britain, counted significant expatriate communities in Tunisia and maintained consulates there. Ties were also commercial; France had advanced a major loan to Tunisia in the mid-19th century and had trading interests.

The opportunity to seize control of Tunisia occurred following the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). Paris did not act immediately; the French parliament remained in an anti-colonial mood and no groundswell of popular opinion mandated a takeover of Tunisia. Several developments spurred France to action. In 1880, the British owners of the railway linking Tunis with the coast put their company up for sale. An Italian concern successfully bid for the enterprise, leaving France worried about possible Italian intervention. Another incident, also in 1880, concerned the sale of a 100 000 hectare property by a former Tunisian prime minister. Negotiations involved complicated arrangements to forestall preemption of the sale by the Bey's government or by proprietors of adjacent tracts of land. A French consortium buying the property believed the deal had been completed, but a British citizen, ostensibly representing neighbouring landholders, preempted the sale and occupied the land (though without paying for it). A judge sent by London to investigate discovered that the British purchaser was acting on behalf of the Bey's government and Italian businessmen; moreover, he discovered that the Briton had used fraud to stake his claim. The sale was cancelled, and French buyers got the property. Paris moved to protect French claims, as London and Berlin gently warned that if France did not act, they might reconsider their go-ahead for French occupation.

French diplomats scrambled to convince unenthusiastic parliamentarians and bureaucrats, all the while looking for a new incident to precipitate intervention. In March 1881, a foray by Tunisian Khroumir tribesmen across the border into Algeria caused the deaths of several Algerians, and four French, providing a pretext for the French.[24] By mid-April, French troops had landed in Tunisia and, on 12 May 1881, forced Bey Muhammad III as-Sadiq to sign the Treaty of Bardo granting France a protectorate over Tunisia. Although soldiers took until May 1882 to occupy the whole country and stamp out resistance, Tunisia had become a new French holding. Germany and Britain remained silent; Italy was outraged but powerless. French public opinion was largely supportive, and the Treaty of Bardo was passed with only one dissenting vote in the Chamber of Deputies and unanimously in the Senate.[25]

As a protectorate, Tunisia's status differed from that of Algeria. The Bey remained in office as head of state, and Tunisia was deemed nominally independent, while existing treaties with other states stayed in force. France, however, took control of Tunisia's foreign affairs, finances, and maintained the right to station military troops within its territory.[25]

Organisation and administration

The Conventions of La Marsa, signed in 1883, by Bey Ali Muddat ibn al-Husayn, formally established the French protectorate. It deprived the Bey of Tunis of control over internal matters by committing him to implement administrative, judicial, and financial reform dictated by France.[26]

In Tunisia: Crossroads of the Islamic and European World, Kenneth J. Perkins writes: "Cambon carefully kept the appearance of Tunisian sovereignty while reshaping the administrative structure to give France complete control of the country and render the beylical government a hollow shell devoid of meaningful powers."[26]

French officials used several methods to control the Tunisian government. They urged the Bey to nominate members of the pre-colonial ruling elite to such key posts as prime-minister, because these people were personally loyal to the Bey and followed his lead in offering no resistance to the French.[27] At the same time, the rulers obtained the dismissal of Tunisians who had supported the 1881 rebellion or had otherwise opposed the extension of French influence.[27] A Frenchman held the office of Secretary-General of the Tunisian government, an office created in 1883 to advise the Prime Minister and oversee the work of the bureaucracy. French experts answerable only to the Secretary-General and the Resident-General managed and staffed those government offices, collectively called the Technical Services, which dealt with finances, public works, education, and agriculture.[27] To help him implement the reforms alluded to in the Conventions of La Marsa, the Resident-General had the power to promulgate executive decrees, reducing the Bey to little more than a figurehead.[27]

To advise the Resident-General, a consultative conference representing French colonists was set up in 1891,[28] and expanded to include appointed Tunisian representatives in 1907.[29] From 1922 until 1954, Tunisian delegates to the Tunisian Consultative Conference were indirectly elected.[30]

Local government

The French authorities left the framework of local government intact, but devised mechanisms to control it. Qaids, roughly corresponding to provincial governors, were the most important figures in local administration.[27] At the outset of the protectorate, some sixty of them had the responsibility of maintaining order and collecting taxes in districts either defined by tribal membership, or by geographical limits. The central government appointed the qaids, usually choosing a person from a major family of the tribe or district to ensure respect and authority. Below the qaids were cheikhs, the leaders of tribes, villages, and town quarters. The central government also appointed them but on the recommendation of the qaids.[27] After the French invasion, most qaids and cheikhs were allowed to retain their post, and therefore few of them resisted the new authorities.[27]

To keep a close watch on developments outside the capital, Tunisia's new rulers organised the contrôleurs civils. These French officials replicated, at the local level, the work of the Resident-General, closely supervising the qaids and sheikhs.[27] After 1884, a network of contrôleurs civils overlay the qaids' administration throughout the country, except in the extreme south. There, because of the more hostile nature of the tribes and the tenuous hold of the central government, military officers, making up a Service des Renseignements (Intelligence Service), fulfilled this duty.[27] Successive Residents-General, fearing the soldiers' tendency toward direct rule — which belied the official French myth that Tunisians continued to govern Tunisia — worked to bring the Service des Renseignements under their control, finally doing so at the end of the century.[27]

Shoring up the debt-ridden Tunisian treasury was one of Cambon's main priorities. In 1884, France guaranteed the Tunisian debt, paving the way for the termination of the International Debt Commission's stranglehold on Tunisian finances. Responding to French pressure, the Bey's government then lowered taxes. French officials hoped that their careful monitoring of tax assessment and collection procedures would result in a more equitable system and stimulate a revival in production and commerce, generating more revenue for the state.[31]

Judicial system

In 1883, French law and courts were introduced; thereafter, French law applied to all French and foreign residents. The other European powers agreed to give up the consular courts they had maintained to protect their nationals from the Tunisian judiciary. The French courts also tried cases in which one litigant was Tunisian, the other European.[31] The protectorate authorities made no attempt to alter Muslim religious courts in which judges, or qadis, trained in Islamic law heard relevant cases.[31] A beylical court handling criminal cases operated under French supervision in the capital. In 1896, similar courts were instituted in the provinces, also under French supervision.

Education

The protectorate introduced new ideas in education. The French director of public education looked after all schools in Tunisia, including religious ones. According to Perkins, "Many colonial officials believed that modern education would lay the groundwork for harmonious Franco-Tunisia relations by providing a means of bridging the gap between Arabo-Islamic and European cultures."[31] In a more pragmatic vein, schools teaching modern subjects in a European language would produce a cadre of Tunisians with the skills necessary to staff the growing government bureaucracy. Soon after the protectorate's establishment, the Directorate of Public Education set up a unitary school system for French and Tunisian pupils designed to draw the two peoples closer together. French was the medium of instruction in these Franco-Arab schools, and their curriculum imitated that of schools in metropolitan France. French-speaking students who attended them studied Arabic as a second language. Ethnic mixing rarely occurred in schools in the cities, in which various religious denominations continued to run elementary schools. The Franco-Arab schools attained somewhat greater success in rural areas but never enrolled more than a fifth of Tunisia's eligible students. At the summit of the modern education system was the Sadiki College, founded by Hayreddin Pasha. Highly competitive examinations regulated admission to Sadiki, and its graduates were almost assured government positions.[32]

World War II

Many Tunisians took satisfaction in France's defeat by Germany in June 1940,[33] but the nationalist parties derived no more substantive benefit from the fall of France. Despite his commitment to terminate the French protectorate, the pragmatic independence leader Habib Bourguiba had no desire to exchange the control of the French Republic for that of Fascist Italy or Nazi Germany, whose state ideologies he abhorred.[34] He feared that associating with the Axis would bring short-term benefit at the cost of long-term tragedy.[34] Following the Second Armistice at Compiègne between France and Germany, the Vichy Government of Marshal Philippe Pétain sent to Tunis as new Resident-General Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva, who had no intention of permitting a revival of Tunisian political activity. The arrests of Taieb Slim and Habib Thameur, central figures in the Neo-Destour party's political bureau were a result of this attitude.

The Bey Muhammad VII al-Munsif moved towards greater independence in 1942, but when the Axis were forced out of Tunisia in 1943, the Free French accused him of collaborating with the Vichy Government and deposed him.

Deposing the Bey

The accession of Muhammad VII on 19 June 1942 was a surprise for the Tunisians. Very popular since he convinced his father to defend the Destour in April 1922, he had a reputation for being close to the people. From 10 August, he did not hesitate to enter into conflict with Jean-Pierre Esteva by presenting him with a memorandum grouping together 16 demands inspired by his nationalist friends. On 15 September, the Vichy government sent an end of inadmissibility in response to the monarch. On 12 October, it was the absence of Tunisians among the French directors of the administration that provoked his anger.

The end of the World War II means the return in force of the French protectorate in Tunisia. The first victim was Moncef Bey who took advantage of the weakening of the French to publicize the Tunisian cause. Little suspected of having collaborated with the Axis powers, he can only be blamed for the decorations awarded on 12 April to German and Italian generals. He was however deposed by a decree of the general of Free France, Henri Giraud, on 13 May 1943 and exiled to Laghouat in the Franco-Algerian South.

He was replaced by Lamine Bey who accepted the throne despite the conditions under which his predecessor was forced to abdicate. Rejected by a large part of the Tunisian population, he only gained his legitimacy on the death of Moncef on 1 September 1948, which put an end to the hopes of Tunisians to see the Nationalist Bey return to the throne.

Independence

Decolonisation proved a protracted and controversial affair. In Tunisia, nationalists demanded the return of the deposed Bey and institutional reform.[35] In 1945, the two Destour parties joined other dissident groups to petition for autonomy. The following year, Habib Bourguiba and the Néo-Destour Party switched their aim to independence. Fearing arrest, Bourguiba spent much of the next three years in Cairo, where in 1950, he issued a seven-point manifesto demanding the restitution of Tunisian sovereignty and election of a national assembly.[35] A conciliatory French government acknowledged the desirability of autonomy, although it warned that this would come only at an unspecified time in the future; Paris proposed French and Tunisian ”co-sovereignty” over the protectorate. An accord signed the next year, which granted increased powers to Tunisian officials, fell short of satisfying nationalists and outraged settlers. New French prime ministers took a harder line and kept Bourguiba under house arrest from 1951 to 1954.[35]

A general strike in 1952 led to violent confrontation between the French and Tunisians, including guerrilla attacks by nationalists. Yet another change in French government, the appointment of Pierre Mendès-France as Prime Minister in 1954, brought a return to gentler approaches. International circumstances — the French defeat in the First Indochina War and insurgency of the Algerian War — spurred French efforts to solve the Tunisian question quickly and peacefully. In a speech in Tunis, Mendès-France solemnly proclaimed the autonomy of the Tunisian government, although France retained control of substantial areas of administration. In 1955, Bourguiba returned to Tunis in triumph. At the same time, the French protectorate of Morocco was terminated which further paved way for Tunisian independence, as decolonisation gained pace. The next year, the French revoked the clause of the Treaty of Bardo that had established the protectorate in 1881 and recognised the independence of the Kingdom of Tunisia under Muhammad VIII al-Amin on 20 March.[36]

See also

Notes and references

- as High Commissioner

- Notes

- References

- Holt & Chilton 1918, p. 220-221.

- Ling 1960, p. 398-99.

- Balch, Thomas William (November 1909). "French Colonization in North Africa". The American Political Science Review. 3 (4): 539–551. doi:10.2307/1944685. JSTOR 1944685. S2CID 144883559.

- Wesseling 1996, pp. 22–23

- Wesseling 1996, p. 22

- Ganiage 1985, pp. 174–75

- Italians in Tunisia (and Maghreb)

- Ling 1960, p. 399.

- Triulzi 1971, p. 155-158; 160–163.

- In August and again in October 1876 Austro-Hungarian minister Gyula Andrássy suggested to the Italian ambassador Robilant that Italy could have occupied Tunis, but Robilant rejected the invitation, and received comfort, along this line, by his Foreign Affairs minister: William L. Langer, The European Powers and the French Occupation of Tunis, 1878–1881, I, The American Historical Review, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Oct. 1925), p. 60.

- René Albrecht-Carrié, "Storia Diplomatica d'Europa 1815–1968", Editori Laterza, Bari-Roma, 1978, pp. 209–210.

- Antonello Battaglia, I rapporti italo-francesi e le linee d'invasione transalpina (1859–1882), Nuova Cultura, Roma, 2013, pp. 41–42.

- Antonello Battaglia, I rapporti italo-francesi e le linee d'invasione transalpina (1859–1882), Nuova Cultura, Roma, 2013, p. 43.

- Antonello Battaglia (Sapienza University of Rome), I rapporti italo-francesi e le linee d'invasione transalpina (1859–1882), Nuova Cultura, Roma, 2013, pp. 45–46.

- Camille Mifort, Combattre au Kef en 1881 quand la Tunisie devint française, ed. MC-Editions, Carthage, 2014, p. 49.

- Hachemi Karoui and Ali Mahjoubi, Quand le soleil s'est levé à l'ouest, ed. Cérès Productions, Tunis, 1983, p. 80.

- Ministère de la Guerre, L'expédition militaire en Tunisie. 1881–1882, éd. Henri-Charles Lavauzelle, Paris, 1898, p. 42

- d'Estournelles de Constant 2002, p. 167.

- Luc Galliot, Essai sur la fièvre typhoïde observée pendant l'expédition de Tunisie, ed. Imprimerie Charaire et fils, Sceaux, 1882, p. 7.

- d'Estournelles de Constant 2002, p. 221-225.

- General R. Hure, page 173 "L' Armee d' Afrique 1830–1962", Charles-Lavauzelle, Paris-Limoges 1977

- General R. Hure, page 175 "L' Armee d' Afrique 1830–1962", Charles-Lavauzelle, Paris-Limoges 1977

- General R. Hure, page 174 "L' Armee d' Afrique 1830–1962", Charles-Lavauzelle, Paris-Limoges 1977

- Ling 1960, p. 406.

- Ling 1960, p. 410.

- Perkins 1986, p. 86.

- Perkins 1986, p. 87.

- Arfaoui Khémais, Les élections politiques en Tunisie de 1881 à 1956, éd. L’Harmattan, Paris, 2011, pp.20–21

- Rodd Balek, La Tunisie après la guerre, éd. Publication du Comité de l’Afrique française, Paris, 1920–1921, p.373

- Arfaoui Khémais, op. cit, pp.45–51

- Perkins 1986, p. 88.

- Perkins 1986, pp. 88–89.

- Perkins 2004, p. 105.

- Perkins 1986, p. 180.

- Aldrich 1996, p. 289.

- Aldrich 1996, p. 290.

- Bibliography

- Aldrich, Robert (1996). Greater France. A history of French Expansion. Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-56740-4.

- d'Estournelles de Constant, Paul (2002). La conquête de la Tunisie. Récit contemporain couronné par l'Académie française (PDF). Paris: éditions Sfar.

- Ganiage, Jean (1985). "North Africa". In Olivier, Roland; Fage, J. D.; Sanderson, G. N. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905. Vol. VI. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22803-4.

- Holt, Lucius Hudson; Chilton, Alexander Wheeler (1918). A History of Europe. From 1862 to 1914. MacMillan.

- Ling, Dwight L. (August 1960). "The French Invasion of Tunisia, 1881". The Historian. 22 (4): 396–412. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1960.tb01666.x. JSTOR 24436566.

- Perkins, Kenneth J. (2004). A History of Modern Tunisia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81124-4.

- Perkins, Kenneth J. (1986). Tunisia. Crossroads of the Islamic and European World. Westview Press. ISBN 0-7099-4050-5.

- Triulzi, Alessandro (1971). "Italian-speaking Communities in Early Nineteenth Century Tunis". Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée. 9: 153–184. doi:10.3406/remmm.1971.1104.

- Wesseling, Henk (1996) [1991]. Verdeel en heers. De deling van Afrika, 1880–1914 [Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880–1914]. Arnold J. Pomerans (trans.). Praeger (Greenwood Publishing Group). ISBN 0-275-95138-3.

- Conte, Alessandro; Sabatini, Gaetano (2018). "Debt and Imperialism in Pre-Protectorate Tunisia, 1867-1870. A Political and Economic Analysis". Journal of European Economic History. 47: 9–32.

Further reading

- Andrew, Christopher. M.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1971). "The French 'Colonial Party'. Its Composition, Aims and Influences". Historical Journal (14): 99–128. doi:10.1017/S0018246X0000741X. S2CID 159549039.

- Andrew, Christopher. M.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1976). "French Business and the French Colonialist". Historical Journal (17): 837–866.

- Andrew, Christopher. M.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1974). "The groupe colonial in the French Chamber of Deputies, 1892–1932". Historical Journal (19): 981–1000.

- Andrew, Christopher. M.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1981). France Overseas. The Great War and the Climax of French Imperialism.

- Cohen, William B. (1971). Rulers of Empire. The French Colonial Service in Africa. Hoover Institution Press.

- Broadley, A. M. (1881). The Last Punic War: Tunis, Past and Present. Vol. I. William Blackwood and Sons.

- Broadley, A. M. (1882). The Last Punic War: Tunis, Past and Present. Vol. II. William Blackwood and Sons.

- Issawi, Charles (1982). An economic History of the Middle East and North Africa. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03443-1.

- Langer, W. (1925–1926). "The European Powers and the French Occupation of Tunis, 1878–1881". American Historical Review. 31 (31): 55–79 & 251–256. doi:10.2307/1904502. JSTOR 1904502.

- Ling, Dwight L. (1979). Morocco and Tunisia, a Comparative History. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-0873-1.

- Murphy, Agnès (1948). The Ideology of French Imperialism, 1871–1881. Catholic University of America Press.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1991). The Scramble for Africa. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81130-4.

- Persell, Stewart Michael (1983). The French Colonial Lobby, 1889–1938. Stanford University Press.

- Priestly, Herbert Ingram (1938). France Overseas. A study of Modern Imperialism.

- Roberts, Stephen Henry (1929). History of French Colonial Policy, 1870–1925.

- Wilson, Henry S. (1994). African Decolonization. Hooder Headline. ISBN 0-340-55929-2.

.svg.png.webp)