Gestrinone

Gestrinone, sold under the brand names Dimetrose and Nemestran among others, is a medication which is used in the treatment of endometriosis.[3][4] It has also been used to treat other conditions such as uterine fibroids and heavy menstrual bleeding and has been investigated as a method of birth control.[5][6][1] Gestrinone is used alone and is not formulated in combination with other medications.[7] It is taken by mouth or in through the vagina.[1][8]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dimetriose, Dimetrose, Nemestran, others |

| Other names | Ethylnorgestrienone; A-46745; R2323; R-2323; RU-2323; 17α-Ethynyl-18-methyl-δ9,11-19-nortestosterone; 17α-Ethynyl-18-methylestra-4,9,11-trien-17β-ol-3-one; 13β-Ethyl-18,19-dinor-17α-pregna-4,9,11-trien-20-yn-17β-ol-3-one |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, vaginal[1] |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Antiprogestogen; Androgen; Anabolic steroid; Steroidogenesis inhibitor; Antiestrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | To albumin[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver (hydroxylation)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 27.3 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine and bile[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.210.606 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H24O2 |

| Molar mass | 308.421 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of gestrinone include menstrual abnormalities, estrogen deficiency, and symptoms of masculinization like acne, seborrhea, breast shrinkage, increased hair growth, and scalp hair loss, among others.[1][8][9][10] Gestrinone has a complex mechanism of action, and is characterized as a mixed progestogen and antiprogestogen, a weak androgen and anabolic steroid, a weak antigonadotropin, a weak steroidogenesis inhibitor, and a functional antiestrogen.[11][1][12][13]

Gestrinone was introduced for medical use in 1986.[14] It has been used extensively in Europe but appears to remains marketed only in a few countries throughout the world.[10][15][7] The medication is not available in the United States.[16] Due to its anabolic effects, the use of gestrinone in competition has been banned by the International Olympic Committee.[17]

Medical uses

Gestrinone is approved for and used in the treatment of endometriosis. It is described as similar in action and effect to danazol, which is also used in the treatment of endometriosis, but is reported to have fewer androgenic side effects in comparison.[18][19] Gestrinone has also been used to shrink uterine fibroids and to reduce menorrhagia.[5][6]

Due to its antigonadotropic effects and ability to inhibit ovulation, gestrinone has been studied as a method of hormonal birth control in women.[1] Large studies across thousands of menstrual cycles have found it to be effective in preventing pregnancy.[1] However, although effective, the pregnancy rate in the largest study conducted was 4.6 per 100 woman-years, which is too high of a failure rate for the medication to be recommended as a safe method of birth control.[1] The medication has also been investigated as an emergency post-coital contraceptive.[20]

Contraindications

The medication is contraindicated in pregnancy, during lactation, and in patients with severe cardiac, chronic kidney disease or liver disease. It is also contraindicated in patients who experienced metabolic and/or vascular disorders during previous estrogen or progestogen therapy, or who are allergic to the medication. The medication is contraindicated in children.

Side effects

The main side effects of gestrinone are androgenic and antiestrogenic in nature.[1][10] In one study of 2.5 mg oral gestrinone twice per week in women, it caused seborrhea in 71%, acne in 65%, breast hypoplasia in 29%, hirsutism in 9%, and scalp hair loss in 9%.[1] In another study, the rate of androgenic side effects was similarly 50%.[1] Other androgenic side effects that have been reported include oily skin and hair, weight gain, voice deepening, and clitoral enlargement, the latter two of which as well as hirsutism may be irreversible.[8][9][10]

Gestrinone also inhibits gonadotropin secretion and causes amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea in a high percentage of women.[1] Similarly, circulating estradiol levels have been found to be reduced by 50%, which may result in estrogen deficiency and associated symptoms.[10] Studies of 2.5 mg oral gestrinone twice per week have found a rate of amenorrhea of 50 to 58%, while a study of 5 mg oral gestrinone per day found a rate of amenorrhea of 100%.[1]

It has been found that vaginal gestrinone shows fewer androgenic side effects and weight gain than oral gestrinone with equivalent effectiveness in endometriosis.[1] Gestrinone appears to show similar effectiveness to danazol in the treatment of endometriosis but with fewer side effects, in particular androgenic side effects.[1][18][19]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

The mechanism of action of gestrinone is complex and multifaceted.[1][18] It shows high affinity for the progesterone receptor (PR), as well as lower affinity for the androgen receptor (AR).[1][18] The medication has mixed progestogenic and antiprogestogenic activity – that is, it is a partial agonist of the PR or a selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM) – and is a weak agonist of the AR, or an anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS).[11][1][12][13] Similarly to danazol, gestrinone acts as a weak antigonadotropin via activation of the PR and AR in the pituitary gland and suppresses the mid-cycle surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during the menstrual cycle without affecting basal levels of these hormones.[1][18] It also inhibits ovarian steroidogenesis and, via activation of the AR in the liver, decreases circulating levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby resulting in increased levels of free testosterone.[1][18][21] In addition to the PR and AR, gestrinone has been found to bind to the estrogen receptor (ER) with relatively "avid" affinity.[22] The medication has functional antiestrogenic activity in the endometrium.[11][1][12][13] Unlike danazol, gestrinone does not appear to bind to SHBG or corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG).[22]

| Compound | PRTooltip Progesterone receptor | ARTooltip Androgen receptor | ERTooltip Estrogen receptor | GRTooltip Glucocorticoid receptor | MRTooltip Mineralocorticoid receptor | SHBGTooltip Sex hormone-binding globulin | CBGTooltip Corticosteroid binding globulin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norethisterone | 155–156 | 43–45 | <0.1 | 2.7–2.8 | 0.2 | ? | ? |

| Norgestrienone | 63–65 | 70 | <0.1 | 11 | 1.8 | ? | ? |

| Levonorgestrel | 170 | 84–87 | <0.1 | 14 | 0.6–0.9 | ? | ? |

| Gestrinone | 75–76 | 83–85 | <0.1, 3–10 | 77 | 3.2 | ? | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were progesterone for the PRTooltip progesterone receptor, testosterone for the ARTooltip androgen receptor, E2 for the ERTooltip estrogen receptor, DEXATooltip dexamethasone for the GRTooltip glucocorticoid receptor, aldosterone for the MRTooltip mineralocorticoid receptor, DHTTooltip dihydrotestosterone for SHBGTooltip sex hormone-binding globulin, and cortisol for CBGTooltip Corticosteroid-binding globulin. Sources: [23][24][25][26] | |||||||

Pharmacokinetics

Gestrinone is bound to albumin in the circulation.[1] It is metabolized in the liver mainly by hydroxylation.[1] Four hydroxylated active metabolites with reduced activity relative to gestrinone have been found to be formed.[1] The elimination half-life of gestrinone is 27.3 hours.[1] The medication is excreted in urine and bile.[1]

Chemistry

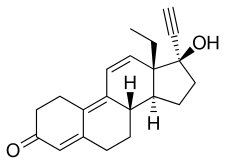

Gestrinone, also known as 17α-ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nor-δ9,11-testosterone, as well as 17α-ethynyl-18-methylestra-4,9,11-trien-17β-ol-3-one or as 13β-ethyl-18,19-dinor-17α-pregna-4,9,11-trien-20-yn-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of testosterone.[27][15] It is more specifically a derivative of norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone) and is a member of the gonane (18-methylestrane) subgroup of the 19-nortestosterone family of progestins.[28][11][29][30] Gestrinone is the C18 methyl derivative of norgestrienone (17α-ethynyl-19-nor-δ9,11-testosterone) and the δ9,11 analogue of levonorgestrel (17α-ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nortestosterone) and is also known as ethylnorgestrienone due to the fact that it is the C13β ethyl variant of norgestrienone.[10][31] It is also the C17α ethynyl and C18 methyl derivative of the AAS trenbolone.[32][33]

The androgenic properties of gestrinone are more exploited in its derivative tetrahydrogestrinone (THG; 17α-ethyl-18-methyl-δ9,11-19-nortestosterone), a designer steroid which is far more potent as both an AAS and progestogen in comparison.[34] THG was banned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003.[35]

History

Gestrinone was introduced for medical use in 1986.[14]

Society and culture

Generic names

Gestrinone is the generic name of the drug and its INNTooltip International Nonproprietary Name, USANTooltip United States Adopted Name, BANTooltip British Approved Name, and JANTooltip Japanese Accepted Name.[27][15][4][7] It is also known by its developmental code names A-46745 and R-2323 (or RU-2323).[27][15][4][7]

Brand names

Gestrinone is or has been marketed under the brand names Dimetriose, Dimetrose, Dinone, Gestrin, and Nemestran.[27][15][7]

Availability

Gestrinone is or has been marketed in Europe, Australia, Latin America, and Southeast Asia,[15][7] though notably not in the United States.[16]

References

- Thomas EJ, Rock J (6 December 2012). Modern Approaches to Endometriosis. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 228, 232, 234. ISBN 978-94-011-3864-2.

- Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- Coutinho EM (1990). "Therapeutic experience with gestrinone". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 323: 233–40. PMID 2406749.

- Morton IK, Hall JM (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- La Marca A, Giulini S, Vito G, Orvieto R, Volpe A, Jasonni VM (December 2004). "Gestrinone in the treatment of uterine leiomyomata: effects on uterine blood supply". Fertility and Sterility. 82 (6): 1694–1696. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.004. PMID 15589885.

- Roy SN, Bhattacharya S (2004). "Benefits and risks of pharmacological agents used for the treatment of menorrhagia". Drug Safety. 27 (2): 75–90. doi:10.2165/00002018-200427020-00001. PMID 14717620. S2CID 33841299.

- "Gestrinone".

- Carp HJ (9 April 2015). Progestogens in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Springer. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-3-319-14385-9.

Side effects [of gestrinone] are due to the androgenic and anti-estrogenic effects including, voice changes, hirsutism, and clittoral enlargement.

- Desai P, Patel P (15 May 2012). Current Practice in Obstetrics and Gynecology Endometriosis. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-93-5025-808-8.

The clinical side effects are dose dependent and similar but less intense than those caused by danazol.12 They include nausea, muscle cramps, and androgenic effects such as weight gain, acne, seborrhea, oily hair/skin, and irreversible voice changes.

- Blackwell RE, Olive DL (6 December 2012). Chronic Pelvic Pain: Evaluation and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-1-4612-1752-7.

Side-effects [of gestrinone] include androgenic and antiestrogenic sequelae. Although most side-effects are mild and transient, several, such as voice changes, hirsutism, and clitoral hypertrophy, are potentially irreversible.

- Berek JS (2007). Berek & Novak's Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1167–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6805-4.

- Carp HJ (9 April 2015). Progestogens in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Springer. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-3-319-14385-9.

- Bromham DR, Booker MW, Rose GL, Wardle PG, Newton JR (1995). "A multicentre comparative study of gestrinone and danazol in the treatment of endometriosis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 15 (3): 188–194. doi:10.3109/01443619509015498. ISSN 0144-3615.

- Ong HH, Allen RC (1 November 1988). "To Market – 1987". In Allen RC (ed.). Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-0-08-058367-9.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 488, 1288. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Ledger W, Schlaff WD, Vancaillie TG (11 December 2014). Chronic Pelvic Pain. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-1-316-21414-5.

- "Helping athletes compete drug-free" (PDF). Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport. May 2000. p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-17. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- Shaw RW, Luesley D, Monga AK (1 October 2010). Gynaecology: Expert Consult: Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2175–. ISBN 978-0-7020-4838-8.

- Gupta S (14 March 2011). A Comprehensive Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-93-5025-112-6.

- "Emergency Contraception Update". International Consortium for Emergency Contraception. October 2006. p. 5. Archived from the original (RTF) on 2006-06-20. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- Arakawa S, Mitsuma M, Iyo M, Ohkawa R, Kambegawa A, Okinaga S, Arai K (June 1989). "Inhibition of rat ovarian 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3 beta-HSD), 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20 lyase by progestins and danazol". Endocrinologia Japonica. 36 (3): 387–394. doi:10.1507/endocrj1954.36.387. PMID 2583058.

- Tamaya T, Fujimoto J, Watanabe Y, Arahori K, Okada H (1986). "Gestrinone (R2323) binding to steroid receptors in human uterine endometrial cytosol". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 65 (5): 439–441. doi:10.3109/00016348609157380. PMID 3490730. S2CID 9229704.

- Delettré J, Mornon JP, Lepicard G, Ojasoo T, Raynaud JP (January 1980). "Steroid flexibility and receptor specificity". J. Steroid Biochem. 13 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(80)90112-0. PMID 7382482.

- Raynaud JP, Bouton MM, Moguilewsky M, Ojasoo T, Philibert D, Beck G, Labrie F, Mornon JP (January 1980). "Steroid hormone receptors and pharmacology". J. Steroid Biochem. 12: 143–57. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(80)90264-2. PMID 7421203.

- Ojasoo T, Raynaud JP, Doé JC (January 1994). "Affiliations among steroid receptors as revealed by multivariate analysis of steroid binding data". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(94)90248-8. PMID 8136304. S2CID 21336380.

- Raynaud JP, Ojasoo T, Bouton MM, Philibert D (1979). Drug Design. pp. 169–214. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-060308-4.50010-X. ISBN 9780120603084.

- Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 595–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Carrell DT, Peterson CM (23 March 2010). Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-4419-1436-1.

- Bland KI, Copeland III EM (9 September 2009). The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-4377-1121-9.

- Lachelin GC (11 September 2013). Introduction to Clinical Reproductive Endocrinology. Elsevier Science. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-1-4831-9380-9.

- Gomel V, Brill A (27 September 2010). Reconstructive and Reproductive Surgery in Gynecology. CRC Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-84184-757-3.

- Thieme E, Hemmersbach P (18 December 2009). Doping in Sports. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-3-540-79088-4.

- Litwack G (2 December 2012). Biochemical Actions of Hormones. Elsevier. pp. 321–. ISBN 978-0-323-15344-7.

- Death AK, McGrath KC, Kazlauskas R, Handelsman DJ (May 2004). "Tetrahydrogestrinone is a potent androgen and progestin". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (5): 2498–2500. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0033. PMID 15126583.

- Hollinger MA (19 October 2007). Introduction to Pharmacology, Third Edition. CRC Press. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4.

Further reading

- Coutinho E, Gonçalves MT, Azadian-Boulanger G, Silva AR (1987). "Endometriosis therapy with gestrinone by oral, vaginal or parenteral administration". Contrib Gynecol Obstet. Contributions to Gynecology and Obstetrics. 16: 227–35. doi:10.1159/000414891. ISBN 978-3-8055-4627-0. PMID 3691096.

- Coutinho EM (1990). "Therapeutic experience with gestrinone". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 323: 233–40. PMID 2406749.