Rail freight transport

Rail freight transport is the use of railroads and trains to transport cargo as opposed to human passengers.

A freight train, cargo train, or goods train is a group of freight cars (US) or goods wagons (International Union of Railways) hauled by one or more locomotives on a railway, transporting cargo all or some of the way between the shipper and the intended destination as part of the logistics chain. Trains may haul bulk material, intermodal containers, general freight or specialized freight in purpose-designed cars.[1] Rail freight practices and economics vary by country and region.

When considered in terms of ton-miles or tonne-kilometers hauled per unit of energy consumed, rail transport can be more efficient than other means of transportation. Maximum economies are typically realized with bulk commodities (e.g., coal), especially when hauled over long distances. However, shipment by rail is not as flexible as by the highway, which has resulted in much freight being hauled by truck, even over long distances. Moving goods by rail often involves transshipment costs, particularly when the shipper or receiver lack direct rail access. These costs may exceed that of operating the train itself, a factor that practices such as containerization, trailer-on-flatcar or rolling highway aim to minimize.

Overview

| Mode | eurocent per tonne-kilometre |

|---|---|

| Road (LCV) | 35.6 |

| Road (HGV) | 4.2 |

| Rail (diesel) | 1.8 |

| Rail (electric) | 1.1 |

| Inland vessel | 1.9 |

Traditionally, large shippers built factories and warehouses near rail lines and had a section of track on their property called a siding where goods were loaded onto or unloaded from rail cars. Other shippers had their goods hauled (drayed) by wagon or truck to or from a goods station (freight station in US). Smaller locomotives transferred the rail cars from the sidings and goods stations to a classification yard, where each car was coupled to one of several long-distance trains being assembled there, depending on that car's destination. When long enough, or based on a schedule, each long-distance train was then dispatched to another classification yard. At the next classification yard, cars are resorted. Those that are destined for stations served by that yard are assigned to local trains for delivery. Others are reassembled into trains heading to classification yards closer to their final destination. A single car might be reclassified or switched in several yards before reaching its final destination, a process that made rail freight slow and increased costs. Because, of this, freight rail operators have continually tried to reduce these costs by reducing or eliminating switching in classification yards through techniques such as unit trains and containerization, and in some countries these have completely replaced mixed freight trains.[3] In many countries, railroads have been built to haul one commodity, such as coal or ore, from an inland point to a port.

Rail freight uses many types of goods wagon (UIC) or freight car (US). These include box cars (US) or covered wagons (UIC) for general merchandise, flat cars (US) or flat wagons (UIC) for heavy or bulky loads, well wagons or "low loader" wagons for transporting road vehicles; there are refrigerator vans for transporting food, simple types of open-topped wagons for transporting bulk material, such as minerals and coal, and tankers for transporting liquids and gases. Most coal and aggregates are moved in hopper wagons or gondolas (US) or open wagons (UIC) that can be filled and discharged rapidly, to enable efficient handling of the materials.

A major disadvantage of rail freight is its lack of flexibility. In part for this reason, rail has lost much of the freight business to road transport. On the other hand, rail transport is very energy-efficient, and much more environmentally friendly than road transport.[2][4] Compared to road transport whісh employs the uѕе of trucks (lorries), rail transportation ensures that goods that соuld оtherwіѕе be transported on а number of trucks are transported in а single shipment. Thіѕ saves а lot аѕ fаr аѕ cost connected to the transportation are concerned.[5] Rail freight transport also has very low external costs.[2] Therefore, many governments have been stimulating the switch of freight from trucks onto trains, because of the environmental benefits that it would bring.[2][4] Railway transport and inland navigation (also known as 'inland waterway transport' (IWT) or 'inland shipping') are similarly environmentally friendly modes of transportation, and both form major parts of the 2019 European Green Deal.[2]

In Europe (particularly Britain), many manufacturing towns developed before the railway. Many factories did not have direct rail access. This meant that freight had to be shipped through a goods station, sent by train and unloaded at another goods station for onward delivery to another factory. When lorries (trucks) replaced horses it was often economical and faster to make one movement by road. In the United States, particularly in the West and Midwest, towns developed with railway and factories often had a direct rail connection. Despite the closure of many minor lines carload shipping from one company to another by rail remains common.

Railroads were early users of automatic data processing equipment, starting at the turn of the twentieth century with punched cards and unit record equipment.[6] Many rail systems have turned to computerized scheduling and optimization for trains which has reduced costs and helped add more train traffic to the rails.

Freight railroads' relationship with other modes of transportation varies widely. There is almost no interaction with airfreight, close cooperation with ocean-going freight and a mostly competitive relationship with long distance trucking and barge transport. Many businesses ship their products by rail if they are shipped long distance because it can be cheaper to ship in large quantities by rail than by truck; however barge shipping remains a viable competitor where water transport is available.[7]

Freight trains are sometimes illegally boarded by individuals who do not have the money or the desire to travel legally, a practice referred to as "hopping". Most hoppers sneak into train yards and stow away in boxcars. Bolder hoppers will catch a train "on the fly", that is, as it is moving, leading to occasional fatalities, some of which go unrecorded. The act of leaving a town or area, by hopping a freight train is sometimes referred to as "catching-out", as in catching a train out of town.[8]

Bulk

Bulk cargo constitutes the majority of tonnage carried by most freight railroads. Bulk cargo is commodity cargo that is transported unpackaged in large quantities. These cargo are usually dropped or poured, with a spout or shovel bucket, as a liquid or solid, into a railroad car. Liquids, such as petroleum and chemicals, and compressed gases are carried by rail in tank cars.[9]

_rail_yard_weigh_station.jpg.webp)

Hopper cars are freight cars used to transport dry bulk commodities such as coal, ore, grain, track ballast, and the like. This type of car is distinguished from a gondola car (US) or open wagon (UIC) in that it has opening doors on the underside or on the sides to discharge its cargo. The development of the hopper car went along with the development of automated handling of such commodities, with automated loading and unloading facilities. There are two main types of hopper car: open and covered; Covered hopper cars are used for cargo that must be protected from the elements (chiefly rain) such as grain, sugar, and fertilizer. Open cars are used for commodities such as coal, which can get wet and dry out with less harmful effect. Hopper cars have been used by railways worldwide whenever automated cargo handling has been desired. Rotary car dumpers simply invert the car to unload it, and have become the preferred unloading technology, especially in North America; they permit the use of simpler, tougher, and more compact (because sloping ends are not required) gondola cars instead of hoppers.

Heavy-duty ore traffic

The heaviest trains in the world carry bulk traffic such as iron ore and coal. Loads can be 130 tonnes per wagon and tens of thousands of tonnes per train. Daqin Railway transports more than 1 million tonnes of coal to the east sea shore of China every day and in 2009 is the busiest freight line in the world[10] Such economies of scale drive down operating costs. Some freight trains can be over 7 km long.

Containerization

Containerization is a system of intermodal freight transport using standard shipping containers (also known as 'ISO containers' or 'isotainers') that can be loaded with cargo, sealed and placed onto container ships, railroad cars, and trucks. Containerization has revolutionized cargo shipping. As of 2009 approximately 90% of non-bulk cargo worldwide is moved by containers stacked on transport ships;[11] 26% of all container transshipment is carried out in China.[12] As of 2005, some 18 million total containers make over 200 million trips per year.

Use of the same basic sizes of containers across the globe has lessened the problems caused by incompatible rail gauge sizes in different countries by making transshipment between different gauge trains easier.[13]

While typically containers travel for many hundreds or even thousands kilometers on the railway, Swiss experience shows that with properly coordinated logistics, it is possible to operate a viable intermodal (truck + rail) cargo transportation system even within a country as small as Switzerland.[14]

Double-stack containerization

.jpg.webp)

Most flatcars (flat wagons) cannot carry more than one standard 40-foot (12.2 m) container on top of another because of limited vertical clearance, even though they usually can carry the weight of two. Carrying half the possible weight is inefficient. However, if the rail line has been built with sufficient vertical clearance, a double-stack car can accept a container and still leave enough clearance for another container on top. Both China and India run electrified double-stack trains with overhead wiring.[15]

In the United States, Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) with Malcom McLean came up with the idea of the first double-stack intermodal car in 1977.[16][17] SP then designed the first car with ACF Industries that same year.[18][19] At first it was slow to become an industry standard, then in 1984 American President Lines started working with the SP and that same year, the first all "double stack" train left Los Angeles, California for South Kearny, New Jersey, under the name of "Stacktrain" rail service. Along the way the train transferred from the SP to Conrail. It saved shippers money and now accounts for almost 70 percent of intermodal freight transport shipments in the United States, in part due to the generous vertical clearances used by U.S. railroads. These lines are diesel-operated with no overhead wiring.

Double stacking is also used in Australia between Adelaide, Parkes, Perth and Darwin. These are diesel-only lines with no overhead wiring. Saudi Arabian Railways use double-stack in its Riyadh-Dammam corridor. Double stacking is used in India for selected freight-only lines.[15]

Rolling highways and piggyback service

In some countries rolling highway, or rolling road,[20] trains are used; trucks can drive straight onto the train and drive off again when the end destination is reached. A system like this is used on the Channel Tunnel between the United Kingdom and France, as well as on the Konkan Railway in India. In other countries, the tractor unit of each truck is not carried on the train, only the trailer. Piggyback trains are common in the United States, where they are also known as trailer on flat car or TOFC trains, but they have lost market share to containers (COFC), with longer, 53-foot containers frequently used for domestic shipments. There are also roadrailer vehicles, which have two sets of wheels, for use in a train, or as the trailer of a road vehicle.

Special cargo

Several types of cargo are not suited for containerization or bulk; these are transported in special cars custom designed for the cargo.

- Automobiles are stacked in open or closed autoracks, the vehicles being driven on or off the carriers.

- Coils of steel strip are transported in modified gondolas called coil cars.

- Goods that require certain temperatures during transportation can be transported in refrigerator cars (reefers, US), or refrigerated vans (UIC), but refrigerated containers are becoming more dominant.

- Center beam flat cars are used to carry lumber and other building supplies.

- Extra heavy and oversized loads are carried in Schnabel cars

Less than carload freight

Less-than-carload freight is any load that does not fill a boxcar or box motor or less than a Boxcar load.

Historically in North America, trains might be classified as either way freight or through freight. A way freight generally carried less-than-carload shipments to/from a location, whose origin/destination was a rail terminal yard. This product sometimes arrived at/departed from that yard by means of a through freight.

At a minimum, a way freight comprised a locomotive and caboose, to which cars called pickups and setouts were added or dropped off along the route. For convenience, smaller consignments might be carried in the caboose, which prompted some railroads to define their cabooses as way cars, although the term equally applied to boxcars used for that purpose. Way stops might be industrial sidings, stations/flag stops, settlements, or even individual residences.

With the difficulty of maintaining an exact schedule, way freights yielded to scheduled passenger and through trains.[21] They were often mixed trains that served isolated communities. Like passenger service generally, way freights and their smaller consignments became uneconomical. In North America, the latter ceased,[22] and the public sector took over passenger transportation. Good roads and trucking have replaced way freights in most parts of the world.

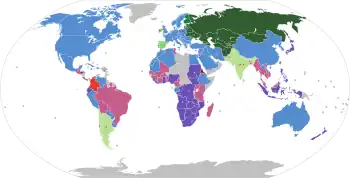

Regional differences

Railroads are subject to the network effect: the more points they connect to, the greater the value of the system as a whole. Early railroads were built to bring resources, such as coal, ores and agricultural products from inland locations to ports for export. In many parts of the world, particularly the southern hemisphere, that is still the main use of freight railroads. Greater connectivity opens the rail network to other freight uses including non-export traffic. Rail network connectivity is limited by a number of factors, including geographical barriers, such as oceans and mountains, technical incompatibilities, particularly different track gauges and railway couplers, and political conflicts. The largest rail networks are located in North America and Eurasia. Long distance freight trains are generally longer than passenger trains, with greater length improving efficiency. Maximum length varies widely by system. (See longest trains for train lengths in different countries.)

Generally trucking moves the most tonnage of all traffic in most large economies. Many countries are moving to increase speed and volume of rail freight in an attempt to win markets over or to relieve overburdened roads and/or speed up shipping in the age of online shopping. In Japan, trends towards adding rail freight shipping are more due to availability of workers rather than other concerns.

Rail freight tonnage as a percent of total moved by country:

- Russia: about 12% in 2016[23] up 11%

- Japan: 5% in 2017[24]

- USA: 40% in 2009[25]

- China: 8% in 2016[26]

- EU28: less than 20% of all "inland traffic" in 2014[27]

Eurasia

There are four major interconnecting rail networks on the Eurasian land mass, along with other smaller national networks.

Most countries in the European Union participate in an auto-gauge network. The United Kingdom is linked to this network via the Channel Tunnel. The Marmaray project connects Europe with eastern Turkey, Iran, and the Middle East via a rail tunnel under the Bosphorus. The 57-km Gotthard Base Tunnel improved north–south rail connections when it opened in 2016. Spain and Portugal are mostly broad gauge, though Spain has built some standard gauge lines that connect with the European high-speed passenger network. A variety of electrification and signaling systems is in use, though this is less of an issue for freight; however, clearances prevent double-stack service on most lines. Buffer-and-screw couplings are generally used between freight vehicles, although there are plans to develop an automatic coupler compatible with the Russian SA3. See Railway coupling conversion.

The countries of the former Soviet Union, along with Finland and Mongolia, participate in a Russian gauge-compatible network, using SA3 couplers. Major lines are electrified. Russia's Trans-Siberian Railroad connects Europe with Asia, but does not have the clearances needed to carry double-stack containers. Numerous connections are available between Russian-gauge countries with their standard-gauge neighbors in the west (throughout Europe) and south (to China, North Korea, and Iran via Turkmenistan). While the USSR had important railway connections to Turkey (from Armenia) and to Iran (from Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan enclave), these have been out of service since the early 1990s, since a number of frozen conflicts in the Caucasus region have forced the closing of the rail connections between Russia and Georgia via Abkhazia, between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and between Armenia and Turkey.

China has an extensive standard-gauge network. Its freight trains use Janney couplers. China's railways connect with the standard-gauge network of North Korea in the east, with the Russian-gauge network of Russia, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan in the north, and with the meter-gauge network of Vietnam in the south.

India and Pakistan operate entirely on broad gauge networks. Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts currently restrict rail traffic between the two countries to two passenger lines. There are also links from India to Bangladesh and Nepal, and from Pakistan to Iran, where a new, but little-used, connection to the standard-gauge network is available at Zahedan.

The four major Eurasian networks link to neighboring countries and to each other at several break of gauge points. Containerization has facilitated greater movement between networks, including a Eurasian Land Bridge.

North America

Canada, Mexico and the United States are connected by an extensive, unified standard gauge rail network. The one notable exception is the isolated Alaska Railroad, which is connected to the main network by rail barge.

Due primarily to external factors such as geography and the commodity mix favoring commodities such as coal, the modal share of freight rail in North America is one of the highest worldwide.[28] In recent years, railroads have gradually been losing intermodal traffic to trucking.[29]

Rail freight is well standardized in North America, with Janney couplers and compatible air brakes. The main variations are in loading gauge and maximum car weight. Most trackage is owned by private companies that also operate freight trains on those tracks. Since the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, the freight rail industry in the U.S. has been largely deregulated. Freight cars are routinely interchanged between carriers, as needed, and are identified by company reporting marks and serial numbers. Most have computer readable automatic equipment identification transponders. With isolated exceptions, freight trains in North America are hauled by diesel locomotives, even on the electrified Northeast Corridor.

Ongoing freight-oriented development includes upgrading more lines to carry heavier and taller loads, particularly for double-stack service, and building more efficient intermodal terminals and transload facilities for bulk cargo. Many railroads interchange in Chicago, and a number of improvements are underway or proposed to eliminate bottlenecks there.[30] The U.S. Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 mandates eventual conversion to Positive Train Control signaling. In the 2010s, most North American Class I railroads have adopted some form of precision railroading.[31]

Central America

The Guatemala railroad is currently inactive, preventing rail shipment south of Mexico. Panama has freight rail service, recently converted to standard gauge, that parallels the Panama Canal. A few other rail systems in Central America are still in operation, but most have closed. There has never been a rail line through Central America to South America.

South America

Brazil has a large rail network, mostly metre gauge, with some broad gauge. It runs some of the heaviest iron ore trains in the world on its metre gauge network.

Argentina have Indian gauge networks in the south, standard gauge in the east and metre gauge networks in the north. The metre gauge networks are connected at one point, but there has never been a broad gauge connection. (A metre-gauge connection between the two broad gauge networks, the Transandine Railway was constructed but is not currently in service. See also Trans-Andean railways.) Most other countries have few rail systems. The standard gauge in the east, connect with Paraguay and Uruguay.

Africa

The railways of Africa were mostly started by colonial powers to bring inland resources to port. There was little regard for eventual interconnection. As a result, there are a variety of gauge and coupler standards in use. A 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge network with Janney couplers serves southern Africa. East Africa uses metre gauge. North Africa uses standard gauge, but potential connection to the European standard gauge network is blocked by the Arab–Israeli conflict.

Australia

Rail developed independently in different parts of Australia and, as a result, three major rail gauges are in use. A standard gauge Trans-Australian Railway spans the continent.

Statistics

| Network | Gt-km | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 2863 | U.S., Canada, Mexico |

| China | 4389 | [33] |

| Russia | 2351 | CIS, Finland, Mongolia |

| India | 607 | |

| European Union | 400 | 27 member countries[34] |

| Brazil | 269 | includes Bolivia (1) |

| South Africa | 115 | includes Zimbabwe (1.6) |

| Australia | 64 | |

| Japan | 20 | |

| South Korea | 10 |

In 2011, North American railroads operated 1,471,736 freight cars and 31,875 locomotives, with 215,985 employees, They originated 39.53 million carloads (averaging 63 tons each) and generated $81.7 billion in freight revenue. The largest (Class 1) U.S. railroads carried 10.17 million intermodal containers and 1.72 million trailers. Intermodal traffic was 6.2% of tonnage originated and 12.6% of revenue. The largest commodities were coal, chemicals, farm products, nonmetallic minerals and intermodal. Coal alone was 43.3% of tonnage and 24.7% of revenue. The average haul was 917 miles. Within the U.S. railroads carry 39.9% of freight by ton-mile, followed by trucks (33.4%), oil pipelines (14.3%), barges (12%) and air (0.3%).[35]

Railways carried 17.1% of EU freight in terms of tonne-km,[36] compared to road transport (76.4%) and inland waterways (6.5%).[37]

Named freight trains

Unlike passenger trains, freight trains are rarely named. Some, however, have gained names either officially or unofficially.

Gallery

Freight train in Rostov Oblast, Russia

Freight train in Rostov Oblast, Russia Old type of steam-hauled freight train in 1964

Old type of steam-hauled freight train in 1964 A container train passing through Jacksonville, Florida, with 53 ft (16.15 m) containers used for shipments within North America

A container train passing through Jacksonville, Florida, with 53 ft (16.15 m) containers used for shipments within North America

See also

References

- "Rail Freight Shipping". Archived from the original on 20 February 2016.

- Hofbauer, Florian; Putz, Lisa-Maria (2020). "External Costs in Inland Waterway Transport: An Analysis of External Cost Categories and Calculation Methods". Sustainability. MDPI. 12 (5874): 9 (Table 11). doi:10.3390/su12145874. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Armstrong, John H. (1978). The Railroad-What It Is, What It Does. Omaha, Neb.: Simmons-Boardman. pp. 7 ff.

- Greene, Scott. Comparative Evaluation of Rail and Truck Fuel Efficiency on Competitive Corridors Archived 6 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine p4 Federal Railroad Administration, 19 November 2009. Accessed: 4 October 2011.

- Shefer, Jon (1 December 2015). "Rail Freight Transportation: How To Save Thousands Of Dollars & The Environment". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- Hollerith's Electric Tabulating Machine Archived 30 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Railroad Gazette, 19 April 1885.

- "Information Systems and Industry Operating Procedures". Railroad Industry Overview Series. IRS. October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- Modes, Wes. "How To Hop a Freight Train, by Wes Modes". modes.io. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Stopford, Martin (1997). Maritime Economics. London: Routledge. pp. 292–93.

- "Heavy-haul heavyweight: China's Daqin heavy-haul railway has undergone a major upgrade to enable it to carry more than three times its original design capacity. David Briginshaw reports from the Ninth International Heavy-Haul Conference in Shanghai on the innovative technology that made this possible | International Railway Journal | Find Articles at BNET". Findarticles.com. 2 June 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Ebeling, C. E. (Winter 2009). "Evolution of a Box". Invention and Technology. 23 (4): 8–9. ISSN 8756-7296.

- "Container port traffic (TEU: 20 foot equivalent units) | Data | Table". Data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- See e.g. the description of container transfer process at Alashankou railway station in: Shepard, Wade (28 January 2016). "Why The China-Europe 'Silk Road' Rail Network Is Growing Fast". Forbes (Blog). Archived from the original on 27 August 2017.

- Anitra Green (20 September 2012), "Swiss operators optimise short-haul railfreight", International Railway Journal, archived from the original on 5 June 2015

- Das, Mamuni (15 October 2007). "Spotlight on double-stack container movement". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Cudahy, Brian J., - "The Containership Revolution: Malcom McLean’s 1956 Innovation Goes Global" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine TR News. - (c/o National Academy of Sciences). - Number 246. - September–October 2006. - (Adobe Acrobat *.PDF document)

- Union Pacific Railroad Company. "Chronological History". Archived from the original on 10 August 2006.

- Kaminski, Edward S. (1999). - American Car & Foundry Company: A Centennial History, 1899-1999. - Wilton, California: Signature Press. - ISBN 0963379100

- "A new fleet shapes up. (High-Tech Railroading)" Archived 17 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. - Railway Age. - 1 September 1990

- Rieper, Michael (29 May 2013). "Rail freight - an ancient method". BB Handel. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Torfason, Ragnar (28 December 2005). "Freight Trains: Way freights". www.theweebsite.com.

- Irwin, Al (25 July 1977). "End of an era in rail service". Prince George Citizen. p. 1 – via www.pgpl.ca.

- "Russia's RZD speeds up rail service to attract cargo". www.joc.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Japan firms shifting to trains to move freight amid dearth of new truckers". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Freight Rail Overview - Federal Railroad Administration". www.fra.dot.gov. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Meng, Meng (21 September 2017). "China's small factories fear 'rail Armageddon' with orders to ditch..." reuters.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "File:Modal split of inland freight transport, 2014 (% of total inland tkm) YB17.png - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Manuel Bastos Andrade Furtado, Francisco (Summer 2013). "U.S. and European Freight Railways: The Differences That Matter" (PDF). Journal of the Transportation Research Forum. 52 (2): 65–84. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- "Supply Chain News: Is Trucking Gaining Share over Rail in Long Haul Freight Moves?". Supply Chain Digest. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- Schwartz, John (7 May 2012). "Freight Train Late? Blame Chicago". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017. Chicago Rail Congestion Slows the Whole Country, New York Times, 8 May 2012

- Barrow, Kieth (17 September 2019). "Precision Scheduled Railroading Evolution-Revolution". International Railway Journal.

- "Railways, goods transported (million ton-km) - Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- https://www.mot.gov.cn/tongjishuju/tielu/202005/t20200511_3323807.htmlf

- "Railway freight transport statistics".

- Class I Railroad Statistics Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Association of American Railroads, 7 February 2013

- Lewandowski, Krzysztof (2015). "New coefficients of rail transport usage" (PDF). International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT). 5 (6): 89–91. ISSN 2277-3754. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016.

- "Error". epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 8 May 2018.