Kadazan-Dusun

Kadazan-Dusun (also written as Kadazandusun or Mamasok Kadazan-Dusun) are an amalgamation of the two closely related indigenous peoples in Sabah, Malaysia that is Kadazan and Dusun people. The Kadazandusun is the largest ethnic group in the state.[2] They are also known as Mamasok Sabah, meaning "indigenous people of Sabah". The traditional worldview according to Kadazan-Dusun tradition mentiones that they are the descendants of Nunuk Ragang. Kadazan-Dusun is recognised as an indigenous nation of Borneo with documented heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) since 2004.[3] Kadazan-Dusun is part of bumiputera group in Malaysia and has its own special rights from land rights, rivers, education and maintaining their own customs.

Kadazandusun priests and priestesses attires during the opening ceremony of Kaamatan 2014 at Hongkod Koisaan, the unity hall of KDCA | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 555,647 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Sabah, Federal Territory of Labuan, Peninsular Malaysia) | |

| Languages | |

| Dusunic languages (especially Dusun and Kadazan), Sabah Malay, Malaysian, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Mainly Roman Catholic) (74.8%), Sunni Islam (22.6%), Momolianism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dusun, Rungus, Kadazan, Orang Sungai, Murut, Lun Bawang/Lun Dayeh | |

a Yearbook of Statistics: Sabah, 2002 & Sabah Statistics 2020 Data |

Several organisations have been established to safeguard the privileges of Kadazan-Dusun in Malaysia and one of them is Pertubuhan Kadazan-Dusun Murut (KDM) Malaysia based in Donggongon, Penampang, Sabah, Malaysia.

Etymology

In 2004, Richard Francis Tunggolou of Kg. Maang, Penampang wrote an article The Origins and Meanings of the terms “Kadazan” and “Dusun"[4] and carried out an extensive research exploring the many possible explanations and theories about the origins and meanings of the word ‘Kadazan’ and ‘Dusun’. The article may very well confirm that there is no such race as ‘Kadazandusun’ as being propagated by some. Therefore, the Kadazan and Dusun may be as identical to each other but are vastly different in many ways.

The "Kadazan" term is popular among the Tangara/Tangaa' tribe on the west coast of Sabah to refer all the native Sabahan tribes while non-Tangara tribes in the interior and eastern part of the state prefer the term "Dusun". Administratively, the Kadazans were called 'Orang Dusun' by the Sultanate (or more specifically the tax-collector), but in reality, the 'Orang Dusun' were Kadazans. An account of this fact was written by the first census made by the North Borneo Company in Sabah, 1881. Administratively, all Kadazans were categorised as Dusuns.[5][6]

Through the establishment of the KCA – Kadazan Cultural Association (KCA was later renamed to KDCA – Kadazan-Dusun Cultural Association) in 1960, this terminology was corrected and replaced by 'Kadazan', which was also used as the official assignation of the non-Muslim natives by the first Chief Minister of North Borneo, Tun Fuad Stephens @ Donald Stephens. When the Federation of Malaysia was formed in 1963, administratively all Dusuns were referred to as Kadazans which sparked opposition from both Kadazan and Dusun sides who wanted the ethnicity term to be officialised and administrate separately. Initially, there were no conflicts with regard to 'Kadazan' as the identity of the 'Orang Dusun' between 1963 and 1984. However, in 1985 through the KCA, the term Dusun was reintroduced after much pressure from various parties desiring a division between the Kadazan and the 'Orang Dusun' once again. This action only worsened the conflict by developing the "Kadazan or Dusun identity crisis" into "Kadazan versus Dusun feud". It was also a largely successful and a precursor to the fall of the ruling political state party Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS).[5]

In November 1989, through the KCA, PBS coined the new term 'Kadazandusun' to represent both the 'Orang Dusun' and 'Kadazan'. This unified term "Kadazandusun" was unanimously passed as a resolution during the 5th Kadazan Cultural Association's Delegates Conference. During the conference, it was decided that this was the best alternative approach to resolve the "Kadazan versus Dusun" conflicts that had impeded the growth and development of the Kadazan-Dusun since "Kadazan versus Dusun" sentiments were politicised in the early 1960s. It was the best alternative generic identity as well as the most appropriate approach in resolving the "Kadazan versus Dusun" conflicts. Although this action is seen as the best alternative to resolving the ongoing "Kadazan versus Dusun" conflicts since the 1960s, its positive effect is only seen by the year 2000 to the present day when the new generation is no longer in the "Kadazan versus Dusun" feudalism mentality. The unification has since strengthened the ties and brought the Kadazandusun community together as an ethnic group towards more positive and prosperous growth in terms of urbanisation, socio-cultural, economic and political development.[5]

The Orang Sungai or Paitanic group welcomed this resolution, however, the Rungus tribe refused to be called neither as Kadazan, Dusun or any combination of the two. They prefer to be called "Momogun," which means "indigenous people" in Kadazan, Dusun, and Rungus because the three groups belong to the same language family that is Dusunic. Meanwhile, the Muruts and Lundayeh also refused the term, but remain their warm relationship with KDCA and responded positively in ways to unite the two largest Sabahan native groups.

Nowadays, the umbrella term "KDMR" (an acronym for Kadazan, Dusun, Murut, and Rungus) is very popular among the younger generations of the three native groups in Sabah to differ themselves from the Malay or Muslim Bumiputra in the state. Another modification of this term is "Momogun KDMR" in Kadazan-Dusun and Rungus or "Mamagun KDMR" in Murut.

Origins of the term 'Kadazan'

There is no proper historical record that exists pertaining to the origins of the term or its originator. Between the late 1950s and early 1960s, the term "Kadazan" has always been theorised by local folks as derivatives from the word "kakadazan" which means towns, or "kadai" which means shops, the term itself is of a Tangaa' dialect (see Tangga language). The derived term was speculated as a reference to townies, or communities living near shops. This has also been explained in an article by Richard Francis Tunggolou. However, there is evidence that the term has been used long before the 1950s. According to Owen Rutter (The Pagans of North Borneo, 1929, p31), "The Dusun usually describes himself generically as a tulun Tindal (landsman), or on the West Coast, particularly at Papar, as a Kadazan".[7] Rutter started working in Sabah from 1910, and left Sabah in 1914. During this time interval, both Penampang and Papar district was yet to be developed as towns, therefore rejects the derivation theory altogether. To seek better information of the true meaning of the term "Kadazan", two high priestesses of Borneo or locally referred to as Bobohizan (Kadazan) or Bobolian (Dusun) was interviewed. When the Bobolian of Dusun Lotud descent was asked on the meaning and definition of "Kadazan", her answer was, "people of the land". This definition was endorsed when Bobohizan Dousia Moujing of Kadazan Penampang descent confirmed that the Kadazan has always been used to describe the real people of the land. That substantiated Rutter's remark on Kadazan people in his book.[5][6]

Origins of the term 'Dusun'

One interesting fact about the Dusuns is that they do not have the word 'Dusun' in their vocabulary, and the term Dusun is an exonym. Unlike the term "Kadazan," which means "people of the land", "Dusun" means "farm/orchard" in the Malay language. It has been suggested that the term 'Orang Dusun' was a term used by the Sultan of Brunei, who was a Malay to refer to the ethnic groups of inland farmers in present-day Sabah.[8] Since most of the west coast of North Borneo was under the influence of the Sultan of Brunei, taxes called 'Duis' (also referred to as the 'River Tax' on the area of southeast of North Borneo) were collected by the sultanate from the 'Orang Dusun', or 'Dusun people'. Hence, since 1881, after the establishment of the British North Borneo Company, the British administration categorised the linguistically similar, 12 main and 33 sub-tribes collectively as 'Dusun' though among themselves they are simply known in their own dialect as just "human" or in their Bobolian term "kadayan" or "kadazan" (in Tangaa version). The Tambanuo and Bagahak, who had converted to Islam for religious reasons, had preferred to be called "Sungei" and "Idaan" respectively although they come from the same sub-tribes. It was also suggested that "Orang Dusun" or "Dusun People" also being used as a term to refer to the forest-dwellers, and farming primitive tribes in the interior of northern Borneo. The usage of this term was then continued by the North Borneo Chartered Company and British colonial governments

Genetic relatedness

According to a Genome-wide SNP genotypic data studies by human genetics research team from University Malaysia Sabah (2018),[9] the Northern Borneon Dusun (Sonsogon, Rungus, Lingkabau and Murut) are closely related to Taiwan natives (Ami, Atayal) and non–Austro-Melanesian Filipinos (Visayan, Tagalog, Ilocano, Minanubu), rather than populations from other parts of Borneo Island.

Origins of the Kadazandusun people

Since the 90s, it has been said that the Kadazandusun people are descendants from China. Most recently, rumour has it that Kadazandusun is closely related, or might be a descendant of the Bunun tribe in Taiwan. Such speculations were made from observed similarities of physical features, and cultures between the Kadazandusun and the Bunun people. However, these rumours were proven irrelevant through both mtDNA and Y-DNA studies.

mtDNA studies

Maternal or Matrilineal Studies Using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), is a test used to explore genetic ancestry from the mother using mtDNA that is obtained from outside of a nucleus cell that isn't contaminated by the presence of Y-chromosome. According to a study published in 2014, by Kee Boon Pin on 150 volunteers from the Kadazandusun people all over the Sabah region, the Kadazandusun people belongs to 9 mtDNA Haplogroups (subjected to the numbers and types of samples involved in the study), with Haplogroup M being the highest frequency, where it represents (60/150 40%) of all maternal lineages. Followed by Haplogroup R (26/150 17.33%), Haplogroup E (22/150 14.67%), Haplogroup B (20/150 13.33%), Haplogroup D (9/150 6%), Haplogroup JT (6/150 4%), Haplogroup N (4/150 2.67%), Haplogroup F (2/150 1.33) and Haplogroup HV (1/150 0.67%). These mtDNA Haplogroups have multiple subgroup distribution into several subclades due to genome mutations for thousands of years. The Haplogroup M subclades founded were: M7b1'2'4'5'6'7'8 (22%), M7c3c (12.67%), M31a2 (0.67%), and M80 (3.33%). The Haplogroup E subclades founded were: E1a1a (8%), E1b+16261 (4.67%), and E2 (2%). The Haplogroup B subclades founded were: B4a1a (3.33%), B4b1 (1.33%), B4b1a+207 (3.33%), B4c2 (0.67%), B4j (0.67%), B5a (2%), and B5a1d (1.33%). The Haplogroup D subclades founded were: D4s (1.33%), and D5b1c1 (4.67%). For Haplogroup F, H, JT, R and N, there were only 1 subclade founded for each haplogroup: F1a4a1 (1.33%), HV2 (0.67%), JT (4%), R9c1a (17.33%), N5 (2.67%).[10] Kee Boon Pin studies confirmed the mtDNA studies conducted by S. G. Tan, on his claim of genetic relation between Kadazandusun to another Taiwan aboriginal, the Paiwan people through the sharing of Haplogroup N as the fundamental DNA.[11] However, in his studies published in 1979, S.G. Tan did not emphasise the significant of this finding to the Out Of Taiwan theory due to the very small percentage of Haplogroup N found in the Kadazandusun test subjects that is insufficient to represent the whole Kadazandusun ethnicity. S.G. Tan did state that the Kadazandusun ethnic have close genome relation to the other ethnics currently present in Borneo, Peninsular Malaysia and the Philippines, including the Ibans, Visayan, Ifugao, Jakun Aboriginal Malays, Dayak Kalimantan, and Tagalog.[11][10]

According to Ken-ichi Shinoda in his study published in November 2014, the Bunun ethnic have the mtDNA of haplogroup B (41.5%), followed by F (30.3%), E (23.6%), M (3.4%) and N (1.1%).[12] Although the Kadazandusun ethnic group shared some of maternal mtDNA haplogroups with the Bunun and Paiwan ethnic groups of Taiwan, the high frequency results of haplogroup M and low frequencies of haplogroups B, E, F and N (insignificant to represent the entire said nation) in the genetics of Kadazandusun ethnicity is enough to refute the theory of Kadazandusun ethnic origin from Taiwan. Kee Boon Pin studies also mentioned that the mtDNA of the Kadazandusun ethnic are more diverse with plenty of variability that is missing which might have depleted (through mutations) in the mtDNA of the Bunun ethnic. Genetic depletion indicates newer mutation from the maternal DNA group. Professor Hirofumi Matsumura, who studies in Genetics and Anthropology, stated that mtDNA sub-haplogroup M7b1'2'4'5'6'7'8 founded in majority of Kadazandusun DNA is one of the oldest mutations from M7 series from haplogroup M that was founded in ancient graveyards in the jungles of Borneo, with estimated age around 12,700 years. It is even older than most discovered ancient M7 series, and spread throughout the Southeast Asia continent creating more M7 mutation series. The mutation series products from M7b1'2'4'5'6'7'8 are present today in several ethnics including Jakun the aboriginal of peninsular Malaysia, Dusun in Brunei, Tagalog and Visayas in the Philippines, and Dayak in Kalimantan and Riau Islands of Indonesia.[13]

Y-DNA studies

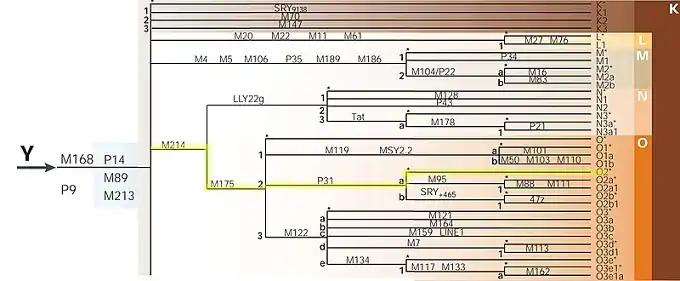

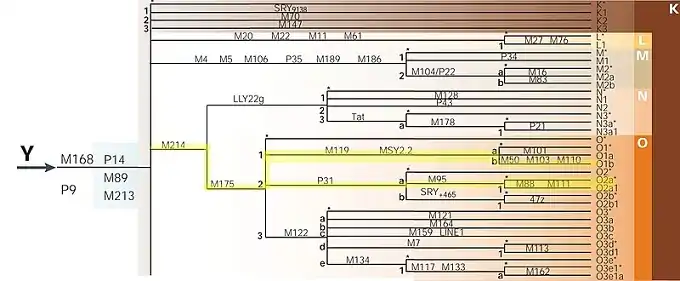

Y chromosome DNA test (Y-DNA test) is a genealogical DNA test that is used to explore a man's patrilineal or direct father's-line ancestry. According to a study by Prof. Dr. Zafarina Zainuddin from Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kadazandusun ethnic belongs to Y-DNA haplogroup of O2-P31 (O-268), which she believes plays an important role in the modern Malay genome sequence.[14][15] O2-P31 is a mutation product of M214 as a maternal haplogroup with the following mutation sequences: M214> M175> P31> O2. This study was also validated by a genetic study group from National Geographic that revealed STR test results through samples taken from Kadazandusun residents of Belud City in 2011. The STR results were: DYS393: 15 DYS439: 12 DYS388: 12 DYS385a: 16 DYS19: 15 DYS389-1: 13 DYS390: 25 DYS385b: 20 DYS391: 11 DYS389-2: NaN DYS426: 11 DYS392: 13, which explains the specific composition of the Y chromosome according to the Y-DNA haplogroup of O2-P31 (O-M268). Mutation sequences for O2-P31 are shown in the Phylogenetic tree below.

According to the Y-DNA study by Jean A Trejaut, Estella S Poloni, and Ju-Chen Yen, the Bunun ethnic in Taiwan belongs to Y-DNA haplogroups of O1a2-M50 and O2a1a-M88. Both of these Y-DNA haplogroups are also the result of mutations of M214 as their maternal Y-DNA haplogroups with the following mutation sequences: M214> M175> MSY2.2> M119> M50> O1a2, and M214> M175> P31> M95> M88> M111 / M88> PK4> O2a1a.[16] Mutation sequences for O1a2-M50 and O2a1a-M88 shown in the Phylogenetic tree below.

The age of Y-DNA haplogroup O2-P31 (O-M268) is estimated to be at around 34,100 years through conducted DNA ageing tests on the ancient human bones discovered in Niah Cave, Sarawak.[17][15] The mean ages of Y-DNA haplogroups of O1a2-M50 and O2a1a-M88 are 33,103 and 28,500, respectively. From the study's result, the claims related to Kadazandusun being ancient migrants from Taiwan are completely irrelevant. This is because the age of the Y-DNA haplogroup O2-P31 belong to the Kadazandusun ethnic group is older compared to the Bunun Y-DNA haplogroups in Taiwan.

Conclusion

Initially, the purpose of starting the genetic haplogroup lineage was to determine the origin of the human lineage. However, the objective is yet to be verified to this day due to a lack of pure evidences that is free from contamination. The results obtained from genetic studies so far can only prove the human global travelling activities, but not as evidence to determine the place of origin of migrating humans.[13] For example, the discovery of the Tianyuan man that has no conclusive answer to his place of origin.[18] Based on the mtDNA and Y-DNA studies, as well as philosophies from genetic and anthropology experts, it is plausible to conclude that Kadazandusun people are indeed the aboriginals of Sabah, and Borneo, as well as one of the leading genetic contributors to Southeast Asian societies.

Culture and society

Religion

The majority of the Kadazandusuns are Christians, mainly Roman Catholics[20] and some Protestants.[21] Islam is also practised by a growing minority.[22][23][24]

The influence of the English-speaking missionaries in British North Borneo during the late 19th century, particularly the Catholic Mill Hill mission,[25] resulted in Christianity, in its Roman Catholic form, rising to prominence amongst Kadazans.[26] A minority are from other Christian denominations, such as Anglicanism and Borneo Evangelical Church (SIB).

Before the missionaries came, animism was widely practiced. The religion is Momolianism i.e. the two-way communication between the unseen spirit world and the seen material world facilitated by the services of a category of Kadazan-Dusun people called Bobohizans/Bobolians. The Kadazan-Dusun belief system centers around the spirit or entity called Bambarayon. It revolved around the belief that spirits ruled over the planting and harvesting of rice, a profession that had been practised for generations. Special rituals would be performed before and after each harvest by a tribal priestess known as a Bobohizan.

Harvest Festival

Harvest Festival or Pesta Kaamatan is an annual celebration by the people of Kadazandusun in Sabah. It is a one-month celebration starting from 1 to 31 May. In modern-day of Kaamatan Festival celebration, 30 and 31 May are the climax dates for the state-level celebration that happens at the place of the yearly Kaamatan Festival host. Today's Kaamatan celebration is very synonymous with beauty pageant competition known as Unduk Ngadau, a singing competition known as Sugandoi, Tamu, non-halal food and beverages stalls, and handicraft arts and cultural performances in traditional houses.[27]

During the old days, Kaamatan was celebrated to give thanks to ancient God and rice spirits for the bountiful harvesting to ensure continuous paddy yield for the next paddy plantation season. Nowadays, the majority of the Kadazan-dusun people have embraced Christianity and Islam. Although the Kaamatan is still celebrated as an annual tradition, it is no longer celebrated for the purpose to meet the demands of the ancestral spiritual traditions and customs, but rather in honouring the customs and traditions of the ancestors. Today, Kaamatan is more symbolic as a reunion time with family and loved ones. Domestically, modern Kaamatan is celebrated as per individual personal aspiration with the option of whether or not to serve the Kadazandusun traditional food and drinks which are mostly non-halal.[28]

Traditional foods and drinks

A few of the most well known traditional food of the Kadazandusun people are hinava, noonsom, pinaasakan, bosou, tuhau, kinoring, sinalau, pork soup and lihing (rice wine) chicken soup. Some of the well known traditional drinks of Kadazandusun are tapai, tumpung, lihing and bahar.[29]

Traditional costumes

The traditional costume of the Kadazandusun is generally called the Koubasanan costume, made out of black velvet fabric with various decorations using beads, flowers, coloured buttons, golden laces, linen, and unique embroidery designs.[30] The traditional costume that is commonly commercialised as the cultural icon of the Kadazandusun people is the Koubasanan costume from the Penampang district. The koubasanan costume from the Penampang district consists of Sinuangga worn by women and Gaung for men. Sinuangga comes with a waistband called Himpogot (made out of connected silver coins, also known as the money belt), Tangkong (made out of copper loops or rings fastened by strings or threads), Gaung (decorated with gold lace and silver buttons) and a hat that is called Siga (made out of weaved dastar fabric). The decorations and designs of the koubasanan costume are usually varied by region.[30] For example, the koubasanan dress design for Kadazandusun women of Penampang usually comes in a set of sleeveless blouse combined with long skirts and no hats, while the koubasanan dress design for Kadazandusun women of Papar comes in a set of long sleeves blouse combined with knee-length skirts and wore with a siung hat. There are over 40 different designs of the Koubasanan costume across Sabah that belongs to different tribes of the Kadazandusun community.[29]

Traditional dance

Sumazau dance is the traditional dance of Kadazandusun. Usually, the sumazau dance is performed by a pair of men and women dancers wearing traditional costumes. Sumazau dance is usually accompanied by the beats and rhythms of seven to eight gongs. The opening movement for sumazau dance is the parallel swing of the arms back and forth at the sides of the body, while the feet springs and move the body from left to right. Once the opening dance moves are integrated with the gong beats and rhythms, the male dancer will chant "heeeeee!" (mamangkis) indicating that it is time to change the dance moves. Upon hearing this chant, dancers will raise their hands to the sides of their body and in line with their chest, and move their wrists and arms up and down resembling the movement of a flying bird. There is plenty of choreography of sumazau dance, but the signature dance move of the sumazau will always be the flying bird arms movement, parallel arms swinging back and forth at the sides of the body, and the springing feet.[29][31]

Traditional music

The Kadazandusun traditional music is usually orchestrated in the form of a band consist of musicians using traditional musical instruments, such as the bamboo flute, sompoton, togunggak, gong, and kulintangan. Musical instruments in Sabah are classified into Cordophones (tongkungon, gambus, sundatang or gagayan), Erophon (suling, turali or tuahi, bungkau, sompoton), and Idofon (togunggak, gong or tagung, kulintangan) and membranophones (kompang, gendang or tontog). The most common musical instruments in Kadazandusun ceremonies are gong and kulintangan. The gong beats usually varies by regions and districts, and the gong beats that is often played at the official Kaamatan celebration in KDCA is the gong beats from the Penampang district.[29][31]

Traditional handicrafts

Kadazandusun people use natural materials as resources in producing handicrafts, including the bamboo, rattan, lias, calabash, and woods. Few of the many handicrafts that are synonym to the Kadazandusun people are wakid, barait, sompoton, pinakol, siung hat, parang, paddy cutter linggaman, and gayang.

Before the mentioned handicrafts were promoted and commercialised to represent the Kadazandusun cultures, they were once tools that were used in daily lives. In fact, some of these handicrafts are still used for its original purpose to this day. Wakid and barait are used to carry harvested crops from farms. Sompoton is a musical instrument. Pinakol is an accessory used in ceremonials and rituals. Parang/machetes, gayang/swords and tandus (a kind of spear) are used as farming and hunting tools, as well as weapons in series of civil wars of the past, which indirectly made the Kadazandusun known as headhunters in the past.[29]

Headhunting practice

The practice of headhunting is one of the ancient traditions practiced by the Kadazan-Dusun community during the times of the civil wars. The Kadazan-Dusun refer to this practice as mangayau and the beheader as pangayou or pangait and tonggorib. In the past, Kadazan-Dusun people often go to sangod (war) and behead their enemy's and keep their skull as trophy and for spiritual reason.

The heads of the beheaded enemies were collected not only as triumph trophies but also for spiritual and traditional medicinal practices. The beheading tradition was not intended for the purpose of war alone, but rather to meet the society's cultural demands and expectations, and to fulfill the sacrificial requirements of the ancient rituals.

In the olden times, a Kadazan-Dusun man's pride and power were measured by his courage and physical strength in combat, as well as the number of heads of fallen enemies that were brought home. The "rule of thumb" for headhunting practice was that the defeated enemy had to be alive during the time of the beheading, as it would be meaningless to behead the deceased. This is due to the traditional Kadazan-Dusun belief that man's intelligence, spirit and courage are in his head (called tandahau), while the heart functions as the life source to the body. In other words, a dead heart means dead (useless) head. Shall any beheader go against this rule, the beheader will be condemned by a curse that will bring unfortunate fate upon him.

Kadazan-Dusun tribes keep their enemy's skulls in a house called bangkawan. Bobolian perform ritual to speak with the spirits in the skulls, now as servants, to ask them to protect their community as they believed the deceased spirits still alive inside the skulls. Before placed in bangkawan, the heads hanged under a huge tree until only the skull remained. A huge rock will placed under the tree. This rock called Sagindai and marked whenever a head hanged under the tree. For example, 10 totok (marks) on the Sagindai rock indicate that ten heads had hanged in that tree.

The three main ethnic groups in Sabah that are known for headhunting practices history are the Kadazan-Dusun, Rungus and the Murut.[32][33]

There are five objectives for the headhunting practices.

- In a great war

- To prove the strength of the heroes and clans over the fallen enemies

- As war victory evidence

- The head will be kept in the house of the skull (bangkawan) of the victorious clan

- For small scale civil war or family feud

- To cease the existence of the enemies and their families

- The head of the enemy will be kept in the victorious family home for the purpose to enslave the enemy's spirit as a housekeeping talisman/amulet

- Empowering manhood

- Beheading is a practice that proves courage and bravery

- A man with no courage and bravery will be out of place in the society and end up spouseless

- Self-promotion as the village head

- A man must obtain at least 10 heads of the enemy clan in order to gain honour and approvals from his own clan

- These 10 heads are also important in convincing his clan that he is worthy as a war leader

- Promoting the bravery of a hero

- The ancient Kadazan-Dusun believed that the strength and spirit of the beheaded enemy would be gained by the beheader

- Enemies beheading is also a way in proving the clan that a hero is worthy as a mighty warrior

The beheaded heads will be kept and maintained using ancient practices and rituals. One of the uses of the beheaded heads is as a housekeeper amulet or talisman. The ancient Kadazan-Dusun people believed that every house should have its guardians. Thus, they will use the "tandahau" spirit from the beheaded head for the purpose of protecting the house and its inhabitants from the attacks of enemies and wild animals. It is also important to place beheaded heads under the newly constructed bridge. The ancient people of Kadazandusun believed that every river had a spirit of water that is called tambaig. The beheaded heads will be placed or hung below the bridge as a peace offering for the tambaig so that the tambaig will not demolish the bridge. Beheaded heads are also used by bobohizan or bobolian for medical purposes, as well as the worship of the ancestors' spirits. The most common weapons used by the ancient headhunters of the Kadazandusun are Ilang, sakuit/mandau machetes, gayang swords, tandus/adus spears, and a taming wood as a shield. This gruesome practice has been banned and no longer practice today. However, there is a rumour saying that primitive Kadazandusun clans living in isolation in the deep jungles are still actively practising the headhunting culture today. Yet, there has been no evidence to support this claim.[32][33]

Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah

The Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah (KDCA), previously known as Kadazan Cultural Association (KCA), is a non-political association of 40 indigenous ethnic communities of Sabah, registered under the Malaysian Societies Act 1966, on 29 April 1966 by the then Deputy Registrar of Societies Malaysia, J. P. Rutherford. It is headed by Huguan Siou Honorable Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Joseph Pairin Kitingan.

The title "Huguan Siou" Office is an institutionalised Paramount Leadership of the Koisaan. The power and responsibility to bestow the Kadazandusun Paramount Leadership Title "Huguan Siou" rests with the KDCA, which, upon the vacancy of the Huguan Siou's Office, may hold an Extraordinary Delegate's Conference to specifically resolve the installation of their Huguan Siou.

However, if no leader is considered worthy of the Huguan Siou's title, the office would rather be left vacant (out of respect for the highly dignified and nearly sacred office of the Kadazandusun's Huguan Siou), until such time as a deserving Kadazandusun leader is undoubtedly established.

The birth of the Society of Kadazan Penampang in 1953 paved the way for the formation of the Kadazan Cultural Association Sabah (KCA) in 1963, which in turn was transformed into the present KDCA on 25 September 1991.

From its inception in the early 1950s, the KDCA has focused much of its efforts on the preservation, development, enrichment, and promotion of the Kadazandusun multi-ethnic cultures. The KDCA's Triennial Delegates Conference provides a forum where the various Kadazandusun multi-ethnic representatives discuss major issues affecting them and their future and take up both individual and collective stands and actions to resolve common challenges.

The KDCA is involved in various activities related to research and documentation, preservation, development, and promotions of the Kadazandusun culture: language and literary works; Bobolians & Rinaits; traditional medicine, traditional food, and beverages; music, songs, dances, and dramas; traditional arts, crafts, and designs; traditional sports; traditional wears and costumes. Lately, along with the growing international co-operation of the world's indigenous peoples, indigenous knowledge, intellectual property, and traditional resource rights conservation, enhancement and protection have also become new areas of the KDCA's concern and responsibility. The KDCA fosters unity, friendship, and co-operation among the multi-racial population of Sabah through its participatory cultural programs and celebrations such as the Village, District and State levels Annual "Kaamatan Festival". It has sent Cultural Performance Troupes on goodwill tours to the other Malaysian States, to neighbouring Asian Countries, to Europe, America, Canada and New Zealand.

KDCA has a youth and students' wing, Kadazandusun Youth Development Movement (KDYDM). The movement's main aims are to encourage more participation of the young generation in the activities of the association and be empowered in various fields so that they would be able to help develop the Kadazandusun community in general.

Kadazandusun sub-ethnic groups

Kadazandusun is the unification term and collective name for more than 70 sub-tribes or suku (payat in Kadazan-Dusun language) who call themselves as Dusun or Kadazan. Before the terms "Kadazan" and exonym "Dusun" coined, there is no name for the nation and every tribes and sub-tribes named after their place of origins or the name of their ancestor or their past leader.

"Ethnicity" or "nation" and "people" or "man" in Dusunic languages is known as tinaru/tina'uh and tulun/tuhun respectively. In Paitanic languages, "people" is lobu. So Kadazan-Dusun people in their native languages called as Tinaru Kadazan-Dusun.

Linguistically, all Kadazan-Dusun tribes (including Rungus) belong to Dusunic languages family except Dusun Bonggi (variety of Molbog language) and Lahad Datu Dusuns who spoke Idaanic languages, while all Orang Sungai tribes spoke Paitanic languages. Paitanic and Dusunic languages families are closely related, together they formed Greater Dusunic languages family.

General classification of Kadazan-Dusun nation :

- Kadazan, or Tangaa', or Tangara

- Dusun

- Rungus or Momogun

- Orang Sungai, or Lobu, or Paitan

However, only the Kadazans and Dusun classified as a single ethnic group by the government while Rungus and Orang Sungai grouped as "Bumiputera Lain" along with Bisaya, Tidong, Sino-natives and other Sabahan natives ethnic group.

List of Kadazan-Dusuns tribes and sub-tribes :

Kadazan, Tangaa', Tangara

- Kadazan Penampang

- Kadazan Papar

- Kadazan Membakut

Dusun

Central Dusun or Bunduliwan :

- Liwan

- Klias River Dusun

- Tindal

- Bundu

- Tinagas

- Talantang

Non-Bunduliwan Dusun :

Northern Dusun :

- Kimaragang

- Sonsogon

- Tagaro or Garo

- Luba

- Tonduk

- Tobilung

- Gobukon

- Sandayo

Eastern Dusun or Labuk-Kinabatangan Kadazan :

- Longgom

- Putih

- Sangau

- Tindakon

- Bayok

- Tanggal

- Tilan-Ilan

- Tandaa'

- Lolobuon

- Kirulu

- Kisayap

- Kisoko

- Koroli

- Kivulu

- Turavid

- Tompulung

- Kotoring

- Sogilitan

- Sungangon

- Dalamason

- Sogo

- Puawang

- Malapi

- Minokok Tompizos

- Mangkaak

- Kunatong

- Korizou/Porizou

- Sukang

Lahad Datu Dusun :

- Subpan or Sagamo

- Begahak

- Buludupi

Momogun Rungus

- Rungus (consist of Kirangavan, Pilapazan, Nuluw, Gandahon, and Tupak clan)

- Gonsomon (sub-tribe of Rungus)

History

Kadazan-Dusun languages

Most of the Kadazan and Dusun languages belong to Dusunic languages family. Dusun Lotud, Dusun Kwijau, and Dusun Tatana came from the Bisayic-branch of the language group. Bonggi language is a variety of Molbog language of Palawan Islands, Philippines. Lahad Datu Dusuns belong to Idaan language family. The Orang Sungai speaks Paitanic languages, closely related to Dusunic languages family, together they form Greater Dusunic languages family. Dusun Gana language belong to Murutic languages family.

Dusunic languages family split into two branches, Dusunic and Bisayic. All Dusunic languages are highly mutually intelligible among each other's but lowly mutually intelligible with Bisayic languages. However, now Bisayic-speaking tribes and other non-Dusunic tribes also know Bunduliwan dialect, a standard Kadazan-Dusun language.

Under the efforts of the Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah, the standard Kadazan-Dusun language is of the central Bundu-Liwan dialect spoken in Bundu and Liwan (now parts of the present-day districts of Ranau, Tambunan, and Keningau). Dusun Bundu-liwan's selection was based on it being the most mutually intelligible when conversing with other Dusun or Kadazan dialect.

| English | Kadazan | Dusun |

|---|---|---|

| What is your name? | Isai ngaan nu? | Isai ngaran nu? |

| My name is John | Ngaan ku nopo nga i John. | Ngaran ku nopo nga i John. |

| How are you? | Onu abal nu? | Nunu kabar nu? |

| I am fine. | Noikot vinasi. | Osonong kopio. |

| Where is Mary? | Nombo zi Mary? | Nonggo i Mary? |

| Thank you | Kotohuadan | Pounsikou/Kotoluadan |

| How much is this? | Pio hoogo/gatang diti? | Piro gatang diti? |

| I don't understand | Au zou kalati | Au oku karati. |

| I miss you | Hangadon zou diau | Langadon oku dika |

| Do you speak English? | Koiho ko moboos do Onggilis? | Koilo ko mimboros do Inggilis? |

| Where are you from? | Nombo o nontodonon nu? | Honggo tadon nu? |

| River | Bavang | Bawang |

Notable Kadazan-Dusun people

- Anifah Aman, former cabinet minister.

- Arthur Joseph Kurup, current Deputy Minister of Science Technology and Innovation, president for United Sabah People's Party (PBRS) and current member of parliament for Pensiangan.

- Bernard Giluk Dompok, Malaysian ambassador to the Vatican from 2016 to 2018, former chief minister of Sabah and former federal minister.

- Clarence Mansul, former deputy minister of Malaysia and former member of parliament for Penampang.[34]

- Cornelius Piong, Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Keningau.

- Darell Leiking, former Malaysian cabinet minister and state assemblyman for Moyog.

- Ewon Benedick, current member of parliament for Penampang.

- Ewon Ebin, former federal minister of Malaysia.

- Fuad Stephens, former first and third chief minister of Sabah and former third Sabah state governor.

- Gunsanad Kina, famous Sabah tribal native chief from Keningau.

- Mohd Hamdan Abdullah, former fourth Sabah state governor.

- Musa Aman, Sabah chief minister from 2003 to 2018.

- Ahmad Koroh, former fifth Sabah governor.

- Mohamad Adnan Robert, former sixth Sabah state governor.

- Jeffrey Kitingan, deputy chief minister of Sabah, current member of Malaysian Parliament for Keningau and state assemblyman for Tambunan.

- Isnaraissah Munirah Majilis, a current member of the Malaysian Parliament for Kota Belud (half Bajau maternal ancestry).

- James Ongkili, former cabinet minister in the 1980s.

- Jonathan Yasin, current member of parliament for Ranau.

- Julius Dusin Gitom, Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Sandakan.

- Juhar Mahiruddin, state governor of Sabah since 2011.

- Joseph Kurup, former federal minister of Malaysia.

- Joseph Pairin Kitingan, former chief minister of Sabah.

- Kasitah Gaddam, former federal Cabinet minister and senator.

- Maximus Ongkili, former minister in the prime minister's Department for Sabah and Sarawak Affairs.

- Peter Anthony, former Sabah state cabinet minister.

- Richard Malanjum, 9th chief justice of Malaysia and the 4th chief judge of the High Court in Sabah and Sarawak.

- Ronald Kiandee, former deputy speaker for the Dewan Rakyat and current member of parliament for Beluran.

- Sedomon Gunsanad Kina, tribal chief of Sabah's interior division during the colonial and early nationhood eras in 1963.

- Wilfred Madius Tangau, former federal minister of Sabah and former deputy chief minister of Sabah.

- Stacy, Malaysian singer.

- Marsha Milan, Malaysian singer and actress.

- Adira, Malaysian singer.

See also

References

- "Taburan Penduduk dan Ciri-ciri asas demografi (Population Distribution and Basic demographic characteristics 2010)" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2015. p. 13 [26/156]

- "People & History". Official Website of the Sabah State Government. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "Language: Kadazandusun, Malaysia". Discovery Channel. 2004 – via UNESCO Multimedia Video & Sound Collections.

- Richard F. Tunggolou (31 October 2004). "The Origins and Meanings of the Terms "Kadazan" and "Dusun"". Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah (KDCA). Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Luping, Herman (7 August 2016). "A History of the Term Kadazandusun". Daily Express. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Origins of the Kadazan People English Literature Essay". UKEssays.com. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Rutter, Owen (1929). The Pagans of North Borneo. London: Hutchinson and Co.

- Staal, J. (1923). "The Dusuns of North Borneo: Their Social Life". Anthropos. 18/19 (4/6): 958–977. JSTOR 40444627.

- Yew, Chee Wei; Hoque, Mohd Zahirul; Pugh‐Kitingan, Jacqueline; et al. (2018). "Genetic Relatedness of Indigenous Ethnic Groups in Northern Borneo to Neighboring Populations from Southeast Asia, as Inferred from Genome‐Wide SNP Data". Annals of Human Genetics. 82 (4): 216–226. doi:10.1111/ahg.12246. PMID 29521412. S2CID 3780230.

- Kee, Boon Pin (2014). Assessment and Analysis of Genomic Diversity and Biomarkers in Sabahan Indigenous Populations (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Malaya.

- Tan, S. G. (1979). "Genetic Relationship between Kadazans and Fifteen other Southeast Asian Races" (PDF). Pertanika. 2 (1): 28–33.

- Shinoda, Ken-ichi; Kakuda, Tsuneo; Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Hideaki; et al. (2014). "Mitochondrial Genetic Diversity of Pingpu Tribes in Taiwan" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Museum of Nature and Science, Series D. 40: 1–12.

- Matsumura, Hirofumi; Shinoda, Ken-ichi; Shimanjuntak, Truman; et al. (2018). Yao, Yong-Gang (ed.). "Cranio-Morphometric and aDNA Corroboration of the Austronesian Dispersal Model in Ancient Island Southeast Asia: Support from Gua Harimau, Indonesia". PLOS ONE. 13 (6). Article e0198689. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398689M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198689. PMC 6014653. PMID 29933384.

- "Kaum Dusun Sabah Bukan Berasal dari China, Tibet Maupun Taiwan". BorneoMail (in Malay). 25 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Karafet, Tatiana M.; Mendez, Fernando L.; Sudoyo, Herawati; et al. (2015). "Improved Phylogenetic Resolution and Rapid Diversification of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup K-M526 in Southeast Asia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (3): 369–373. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.106. PMC 4326703. PMID 24896152.

- Trejaut, Jean A.; Poloni, Estella S.; Yen, Ju-Chen; et al. (2014). "Taiwan Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation and Its Relationship with Island Southeast Asia". BMC Genetics. 15. Article 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-15-77. PMC 4083334. PMID 24965575.

- Curnoe, Darren; Datan, Ipoi; Taçon, Paul S. C.; et al. (2016). "Deep Skull from Niah Cave and the Pleistocene Peopling of Southeast Asia". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. Article 75. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00075.

- Fu, Qiaomei; Meyer, Matthias; Gao, Xing; et al. (2013). "DNA Analysis of an Early Modern Human from Tianyuan Cave, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (6): 2223–2227. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2223F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221359110. PMC 3568306. PMID 23341637.

- "2010 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia" (PDF) (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. p. 107. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Assessment for Kadazans in Malaysia". MAR. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012.

- Koepping, Elizabeth (2004). Paper on Mission to Kadazan of Sabah, Malaysia. IAMS 2004 Conference (Abstract). Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- "Voices of the Earth". Our Planet.

- "More Foreigners In Brunei Embrace Islam". BruneiDirect.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

- "Malay Ultras Diluted Borneo Autonomy". GeoCities. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009.

- Lindsay, Jennifer; Tan, Ying Ying, eds. (2003). Babel or Behemoth: Language Trends in Asia. Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. p. 15. ISBN 981-04-9075-5.

- "Prefectures Apostolic of Borneo". New Advent. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Estelle (29 May 2017). "Kaamatan: Tale of Harvest". AmazingBorneo. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Petronas (29 May 2017). "11 Things About Kaamatan and Gawai You Should Know Before Going to Sabah or Sarawak". Says. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Crystal. "Kadazandusun Food & Art". Padlet. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Traditional Costume of the Penampang Kadazan". Kadazandusun Cultural Association Sabah (KDCA). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Kadazan Traditional Music and Dances". KadazanHomeland.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Bedford, Sam (25 March 2018). "The History of Borneo's Headhunters". Culturetrip. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "The Headhunters of Borneo". KadazanHomeland.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - John Anthony (15 July 2018). "Huguan Siou Legacy of the Kadazandusuns". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 15 July 2018 – via PressReader.

- Tangit, Trixie M. (2005). Planning Kadazandusun (Sabah, Malaysia): Labels, Identity, and Language (MA thesis). University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/11691.