List of Indian inventions and discoveries

This list of Indian inventions and discoveries details the inventions, scientific discoveries and contributions of India, including those from the historic Indian subcontinent and the modern-day republic of India. It draws from the whole cultural and technological history of India, during which architecture, astronomy, cartography, metallurgy, logic, mathematics, metrology and mineralogy were among the branches of study pursued by its scholars.[1] During recent times science and technology in the Republic of India has also focused on automobile engineering, information technology, communications as well as research into space and polar technology.

|

| History of science and technology in the Indian subcontinent |

|---|

| By subject |

For the purpose of this list, the inventions are regarded as technological firsts developed in India, and as such does not include foreign technologies which India acquired through contact. It also does not include technologies or discoveries developed elsewhere and later invented separately in India, nor inventions by Indian emigres in other places. Changes in minor concepts of design or style and artistic innovations do not appear in the lists.

Ancient India

Discoveries

- Indigo (dye): Indigo, a blue pigment and a dye, was used in India, which was also the earliest major centre for its production and processing.[2] The Indigofera tinctoria variety of Indigo was domesticated in India.[2] Indigo, used as a dye, made its way to the Greeks and the Romans via various trade routes, and was valued as a luxury product.[2]

- Jute cultivation: Jute has been cultivated in India since ancient times.[3] Raw jute was exported to the western world, where it was used to make ropes and cordage.[3] The Indian jute industry, in turn, was modernised during the British Raj in India.[3] The region of Bengal was the major centre for Jute cultivation, and remained so before the modernisation of India's jute industry in 1855, when Kolkata became a centre for jute processing in India.[3]

- Power Series: The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics or the Kerala school was a school of mathematics and astronomy founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama in Tirur, Malappuram, Kerala, India. Their work, completed two centuries before the invention of calculus in Europe, provided what is now considered the first example of a power series (apart from geometric series). However, they did not formulate a systematic theory of differentiation and integration.[4]

- Refined sugar: Sugarcane was originally from tropical South Asia and Southeast Asia,[5] with different species originating in India, and S. edule and S. officinarum from New Guinea.[5] The process of producing crystallised sugar from sugarcane was discovered by the time of the Imperial Guptas,[6] and the earliest reference of candied sugar comes from India.[7] The process was soon transmitted to China with travelling Buddhist monks.[7] Chinese documents confirm at least two missions to India, initiated in 647 CE, for obtaining technology for sugar-refining.[8] Each mission returned with results on refining sugar.[8]

Administration

- Local government: presence of municipality in Indus Valley Civilization is characterised by rubbish bins and drainage system throughout urban areas. Megasthenes also mentions presence of a local government in the Mauryan city of Pataliputra.[9][10]

Construction, civil engineering and architecture

- English Bond: The English bond is a form of brickwork with alternating stretching and heading courses, with the headers centred over the midpoint of the stretchers, and perpends in each alternate course aligned. Harappan architecture in South Asia was the first to use the so-called English bond in building with bricks.

- Plumbing: Standardized earthen plumbing pipes with broad flanges making use of asphalt for preventing leakages appeared in the urban settlements of the Indus Valley Civilization by 2700 BC. Earthen pipes were used in the Indus Valley c. 2700 BC for a city-scale urban drainage system,[11]

- Squat toilet: Toilet platforms above drains, in the proximity of wells, are found in several houses of the cities of Mohenjodaro and Harappa from the 3rd millennium BCE.[12]

- Stepwell: Earliest clear evidence of the origins of the stepwell is found in the Indus Valley Civilisation's archaeological site at Mohenjodaro in Pakistan[13] and Dholavira in India.[14] The three features of stepwells in the subcontinent are evident from one particular site, abandoned by 2500 BCE, which combines a bathing pool, steps leading down to water, and figures of some religious importance into one structure.[13] The early centuries immediately before the common era saw the Buddhists and the Jains of India adapt the stepwells into their architecture.[13] Both the wells and the form of ritual bathing reached other parts of the world with Buddhism.[13] Rock-cut step wells in the subcontinent date from 200 to 400 CE.[15] Subsequently, the wells at Dhank (550–625 CE) and stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850–950 CE) were constructed.[15]

- Stupa: The origin of the stupa can be traced to 3rd-century BCE India.[16] It was used as a commemorative monument associated with storing sacred relics.[16] The stupa architecture was adopted in Southeast and East Asia, where it evolved into the pagoda, a Buddhist monument used for enshrining sacred relics.[16]

- Residential University – Nalanda (Nālandā, pronounced [naːlən̪d̪aː]) was a renowned mahavihara (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), eastern India.[17][18][19] Considered by historians to be the world's first residential university[20] and among the greatest centers of learning in the ancient world, it was located near the city of Rajagriha (now Rajgir) and about 90 kilometres (56 mi) southeast of Pataliputra (now Patna). Operating from 427 until 1197 CE,{{sfn| Pinkney|

Music

- Musical Notation: Samaveda text (1200 BC – 1000 BC) contains notated melodies, and these are probably the world's oldest surviving ones.[21]

Finance and banking

- Cheque: There is early evidence of using cheques. In India, during the Maurya Empire (from 321 to 185 BC), a commercial instrument called the adesha was in use, which was an order on a banker desiring him to pay the money of the note to a third person.[22]

Games

- Atya-patya: This variation of tag was being played as early as 100 CE, and was possibly invented by farmers as a way of practicing driving away birds. It was later used as a form of military training in the Chola Dynasty in close relation to the martial art of kalaripayattu.[23]

- Badminton: The game may have originally developed among expatriate officers in British India[24][25]

- Blindfold Chess: Games prohibited by Buddha includes a variant of ashtapada game played on imaginary boards. Akasam astapadam was an ashtapada variant played with no board, literally "astapadam played in the sky". A correspondent in the American Chess Bulletin identifies this as likely the earliest literary mention of a blindfold chess variant.[26]

- Carrom: The game of carrom originated in India.[27] One carrom board with its surface made of glass is still available in one of the palaces in Patiala, India.[28] It became very popular among the masses after World War I. State-level competitions were being held in the different states of India during the early part of the twentieth century. Serious carrom tournaments may have begun in Sri Lanka in 1935 but by 1958, both India and Sri Lanka had formed official federations of carrom clubs, sponsoring tournaments and awarding prizes.[29]

- Chaturanga: The precursor of chess originated in India during the Gupta dynasty (c. 280–550 CE).[30][31][32][33] Both the Persians and Arabs ascribe the origins of the game of Chess to the Indians.[32][34][35] The words for "chess" in Old Persian and Arabic are chatrang and shatranj respectively – terms derived from caturaṅga in Sanskrit,[36][37] which literally means an army of four divisions or four corps.[38][39] Chess spread throughout the world and many variants of the game soon began taking shape.[40] This game was introduced to the Near East from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of Persian nobility.[38] Buddhist pilgrims, Silk Road traders and others carried it to the Far East where it was transformed and assimilated into a game often played on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares.[40] Chaturanga reached Europe through Persia, the Byzantine empire and the expanding Arabian empire.[39][41] Muslims carried Shatranj to North Africa, Sicily, and Spain by the 10th century where it took its final modern form of chess.[40]

- Kabaddi: The game of kabaddi originated in India during prehistory.[42] Suggestions on how it evolved into the modern form range from wrestling exercises, military drills, and collective self-defence but most authorities agree that the game existed in some form or the other in India during the period between 1500 and 400 BCE.[42]

- Kalaripayattu: One of the world's oldest form of martial arts is Kalaripayattu that developed in the southwest state of Kerala in India.[43] It is believed to be the oldest surviving martial art in India, with a history spanning over 3,000 years.[44]

- Kho-kho: This is one of the oldest variations of tag in the world, having been played since as early as the fourth century BCE.[45]

- Ludo: Pachisi originated in India by the 6th century.[46] The earliest evidence of this game in India is the depiction of boards on the caves of Ajanta.[46] A variant of this game, called Ludo, made its way to England during the British Raj.[46]

- Mallakhamba: It is a traditional sport, originating from the Indian subcontinent, in which a gymnast performs aerial yoga or gymnastic postures and wrestling grips in concert with a vertical stationary or hanging wooden pole, cane, or rope.The earliest literary known mention of Mallakhamb is in the 1135 CE Sanskrit classic Manasollasa, written by Someshvara III. It has been thought to be the ancestor of Pole Dancing.

- Nuntaa, also known as Kutkute.[47]

- Seven Stones: An Indian subcontinent game also called Pitthu is played in rural areas has its origins in the Indus Valley Civilization.[48]

- Snakes and ladders: Vaikunta pali Snakes and ladders originated in India as a game based on morality.[49] During British rule of India, this game made its way to England, and was eventually introduced in the United States of America by game-pioneer Milton Bradley in 1943.[49]

- Suits game: Kridapatram is an early suits game, made of painted rags, invented in Ancient India. The term kridapatram literally means "painted rags for playing."[50][51][52][53][54] Paper playing cards first appeared in East Asia during the 9th century.[50][55] The medieval Indian game of ganjifa, or playing cards, is first recorded in the 16th century.[56]

- Table Tennis: It has been suggested that makeshift versions of the game were developed by British military officers in India around the 1860s or 1870s, who brought it back with them.[57]

- Vajra-mushti: refers to a wrestling where knuckleduster like weapon is employed.The first literary mention of vajra-musti comes from the Manasollasa of the Chalukya king Someswara III (1124–1138), although it has been conjectured to have existed since as early as the Maurya dynasty[58][59]

Textile and material production

- Button: Ornamental buttons—made from seashell—were used in the Indus Valley civilisation for ornamental purposes by 2000 BCE.[60] Some buttons were carved into geometric shapes and had holes pierced into them so that they could be attached to clothing by using a thread.[60] Ian McNeil (1990) holds that: "The button, in fact, was originally used more as an ornament than as a fastening, the earliest known being found at Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley. It is made of a curved shell and about 5000 years old."[61]

- Calico: Calico had originated in the subcontinent by the 11th century and found mention in Indian literature, by the 12th-century writer Hemachandra. He has mentioned calico fabric prints done in a lotus design.[62] The Indian textile merchants traded in calico with the Africans by the 15th century and calico fabrics from Gujarat appeared in Egypt.[62] Trade with Europe followed from the 17th century onward.[62] Within India, calico originated in Kozhikode.[62]

- Carding devices: Historian of science Joseph Needham ascribes the invention of bow-instruments used in textile technology to India.[63] The earliest evidence for using bow-instruments for carding comes from India (2nd century CE).[63] These carding devices, called kaman and dhunaki would loosen the texture of the fibre by the means of a vibrating string.[63]

- Cashmere: The fibre cashmere fibre also known as pashm or pashmina for its use in the handmade shawls of Kashmir, India.[64] The woolen shawls made from wool in Indian administered Kashmir find written mention between the 3rd century BCE and the 11th century CE.[65]

- Charkha (Spinning wheel): invented in India, between 500 and 1000 CE.[66]

- Chintz: The origin of Chintz is from the printed all cotton fabric of calico in India.[67] The origin of the word chintz itself is from the Hindi language word चित्र् (chitr), which means an image.[67][68]

- Cotton cultivation: Cotton was cultivated by the inhabitants of the Indus Valley civilisation by the 5th millennium BCE – 4th millennium BCE.[69] The Indus cotton industry was well developed and some methods used in cotton spinning and fabrication continued to be practised until the modern industrialisation of India.[70] Well before the Common Era, the use of cotton textiles had spread from India to the Mediterranean and beyond.[71]

- Single roller cotton gin: The Ajanta Caves of India yield evidence of a single roller cotton gin in use by the 5th century.[72] This cotton gin was used in India until innovations were made in form of foot powered gins.[73] The cotton gin was invented in India as a mechanical device known as charkhi, more technically the "wooden-worm-worked roller". This mechanical device was, in some parts of India, driven by water power.[63]

- Worm drive Cotton gin: The worm drive later appeared in the Indian subcontinent, for use in roller cotton gins, during the Delhi Sultanate in the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries.[74]

- Palampore: पालमपोर् (Hindi language) of Indian origin[75] was imported to the western world—notable England and Colonial America—from India.[76][77] In 17th-century England these hand painted cotton fabrics influenced native crewel work design.[76] Shipping vessels from India also took palampore to colonial America, where it was used in quilting.[77]

- Prayer flags: The Buddhist sūtras, written on cloth in India, were transmitted to other regions of the world.[78] These sutras, written on banners, were the origin of prayer flags.[78] Legend ascribes the origin of the prayer flag to the Shakyamuni Buddha, whose prayers were written on battle flags used by the devas against their adversaries, the asuras.[79] The legend may have given the Indian bhikku a reason for carrying the 'heavenly' banner as a way of signyfying his commitment to ahimsa.[80] This knowledge was carried into Tibet by 800 CE, and the actual flags were introduced no later than 1040 CE, where they were further modified.[80] The Indian monk Atisha (980–1054 CE) introduced the Indian practice of printing on cloth prayer flags to Tibet.[79]

- Tanning (leather): Ancient civilizations used leather for waterskins, bags, harnesses and tack, boats, armour, quivers, scabbards, boots, and sandals. Tanning was being carried out by the inhabitants of Mehrgarh in Ancient India between 7000 and 3300 BCE.[81]

- Roller Sugar Mill: Geared sugar rolling mills first appeared in Mughal India, using the principle of rollers as well as worm gearing, by the 17th century.[82]

Wellbeing

- Indian clubs: The Indian club—which appeared in Europe during the 18th century—was used long by India's native soldiery before its introduction to Europe.[83] During the British Raj the British officers in India performed calisthenic exercises with clubs to keep in physical condition.[83] From Britain the use of club swinging spread to the rest of the world.[83]

- Meditation: The oldest documented evidence of the practice of meditation are wall arts in the Indian subcontinent from approximately 5,000 to 3,500 BCE, showing people seated in meditative postures with half-closed eyes.[84]

- Shampoo: The word shampoo in English is derived from Hindustani chāmpo (चाँपो Hindustani pronunciation: [tʃãːpoː]),[85] and dates to 1762.[86] A variety of herbs and their extracts were used as shampoos since ancient times in India, evidence of early herbal shampoo have been discovered from Indus Valley Civilization site of Banawali dated to 2750–2500 BCE.[87] A very effective early shampoo was made by boiling Sapindus with dried Indian gooseberry (aamla) and a few other herbs, using the strained extract. Sapindus, also known as soapberries or soapnuts, is called Ksuna (Sanskrit: क्षुण)[88] in ancient Indian texts and its fruit pulp contain saponins, a natural surfactant. The extract of Ksuna, creates a lather which Indian texts identify as phenaka (Sanskrit: फेनक),[89] leaves the hair soft, shiny and manageable. Other products used for hair cleansing were shikakai (Acacia concinna), soapnuts (Sapindus), hibiscus flowers,[90][91] ritha (Sapindus mukorossi) and arappu (Albizzia amara).[92] Guru Nanak, the founding prophet and the first Guru of Sikhism, made references to soapberry tree and soap in 16th century.[93] Washing of hair and body massage (champu) during a daily strip wash was an indulgence of early colonial traders in India. When they returned to Europe, they introduced their newly learnt habits, including the hair treatment they called shampoo.[94]

- Yoga: Yoga as a physical, mental, and spiritual practice originated in ancient India.[95]

Medicine

- Ancient Dentistry: The Indus Valley civilisation (IVC) has yielded evidence of dentistry being practised as far back as 7000 BCE. An IVC site in Mehrgarh indicates that this form of dentistry involved curing tooth related disorders with bow drills operated, perhaps, by skilled bead crafters[96][97][98]

- Angina pectoris: The condition was named "hritshoola" in ancient India and was described by Sushruta (6th century BCE).[99]

- Ayurvedic and Siddha medicine: Ayurveda and Siddha are ancient systems of medicine practised in South Asia. Ayurvedic ideas can be found in the Hindu text[100] (mid-first millennium BCE). Ayurveda has evolved over thousands of years, and is still practised today. In an internationalised form, it can be thought of as a complementary and alternative medicine. In village settings, away from urban centres, it is simply "medicine." The Sanskrit word आयुर्वेदः (āyur-vedaḥ) means "knowledge (veda) for longevity (āyur)".[101] Siddha medicine is mostly prevalent in South India, and is transmitted in Tamil, not Sanskrit, texts. Herbs and minerals are basic raw materials of the Siddha therapeutic system whose origins may be dated to the early centuries CE.[102][103]

- Cataract surgery: Cataract surgery was known to the Indian physician Sushruta (6th century BCE).[104] In India, cataract surgery was performed with a special tool called the Jabamukhi Salaka, a curved needle used to loosen the lens and push the cataract out of the field of vision.[105] The eye would later be soaked with warm butter and then bandaged.[105] Though this method was successful, Susruta cautioned that cataract surgery should only be performed when absolutely necessary.[105] Greek philosophers and scientists traveled to India where these surgeries were performed by physicians.[105] The removal of cataract by surgery was also introduced into China from India.[106]

- Leprosy cure: Kearns & Nash (2008) state that the first mention of leprosy is described in the Indian medical treatise Sushruta Samhita (6th century BCE).[107] However, The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine holds that the mention of leprosy, as well as ritualistic cures for it, were described in the Atharva-veda (1500–1200 BCE), written before the Sushruta Samhita.[108]

- Lithiasis treatment: The earliest operation for treating lithiasis, or the formations of stones in the body, is also given in the Sushruta Samhita (6th century BCE).[109] The operation involved exposure and going up through the floor of the bladder.[109]

- Visceral leishmaniasis, treatment of: The Indian (Bengali) medical practitioner Upendranath Brahmachari (19 December 1873 – 6 February 1946) was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929 for his discovery of 'ureastibamine (antimonial compound for treatment of kala azar) and a new disease, post-kalaazar dermal leishmanoid.'[110] Brahmachari's cure for Visceral leishmaniasis was the urea salt of para-amino-phenyl stibnic acid which he called Urea Stibamine.[111] Following the discovery of Urea Stibamine, Visceral leishmaniasis was largely eradicated from the world, except for some underdeveloped regions.[111]

- Ganja was used as herb for ayurverdic medicine development for last 2,000 years. The Sushruta Samhita, an ancient medical treatise, recommends cannabis plant extract for treating respiratory ailments and diarrhoea.

- Plastic surgery – Sushruta's treatise provides the first written record of a cheek flap rhinoplasty, a technique still used today to reconstruct a nose.[112]

- Veterinary Medicine – Shalihotra Samhita is the first text to talk about cures for elephants and equines.

- Otoplasty – Otoplasty (surgery of the ear) was developed in ancient India and is described in the medical compendium, the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta's Compendium, c. 500 AD). The book discussed otoplastic and other plastic surgery techniques and procedures for correcting, repairing and reconstructing ears, noses, lips, and genitalia that were amputated as criminal, religious, and military punishments. The ancient Indian medical knowledge and plastic surgery techniques of the Sushruta Samhita were practiced throughout Asia until the late 18th century; the October 1794 issue of the contemporary British Gentleman's Magazine reported the practice of rhinoplasty, as described in the Sushruta Samhita. Moreover, two centuries later, contemporary practices of otoplastic praxis were derived from the techniques and procedures developed and established in antiquity by Sushruta.[113][114]

- Tonsillectomy - Tonsillectomies have been practiced for over 2,000 years, with varying popularity over the centuries.[115] The earliest mention of the procedure is in "Hindu medicine" from about 1000 BCE

Science

- Fibonacci number: The Fibonacci numbers were first described in Indian mathematics, as early as 200 BC in work by Pingala on enumerating possible patterns of Sanskrit poetry formed from syllables of two lengths.

- Toe stirrup: The earliest known manifestation of the stirrup, which was a toe loop that held the big toe was used in India in as early as 500 BCE[116] or perhaps by 200 BCE according to other sources.[117][118] This ancient stirrup consisted of a looped rope for the big toe which was at the bottom of a saddle made of fibre or leather.[118] Such a configuration made it suitable for the warm climate of most of India where people used to ride horses barefoot.[118] A pair of megalithic double bent iron bars with curvature at each end, excavated in Junapani in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh have been regarded as stirrups although they could as well be something else.[119] Buddhist carvings in the temples of Sanchi, Mathura and the Bhaja caves dating back between the 1st and 2nd century BCE figure horsemen riding with elaborate saddles with feet slipped under girths.[120][121][122] Sir John Marshall described the Sanchi relief as "the earliest example by some five centuries of the use of stirrups in any part of the world".[122] In the 1st century CE horse riders in northern India, where winters are sometimes long and cold, were recorded to have their booted feet attached to hooked stirrups.[117] However the form, the conception of the primitive Indian stirrup spread west and east, gradually evolving into the stirrup of today.[118][121]

Metallurgy, Gems and other Commodities

- Crucible steel: Perhaps as early as 300 BCE—although certainly by 200 BCE—high quality steel was being produced in southern India, by what Europeans would later call the crucible technique.[123] In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.[123]

- Dockyard: The world's earliest enclosed dockyard was built in the Harappan port city of Lothal circa 2600 BC in Gujarat, India.

- Diamond drills: in the 12th century BCE or 7th century BCE, Indians not only innovated use of diamond tipped drills but also invented double diamond tipped drills for bead manufacturing.[124]

- Diamond cutting and polishing: The technology of cutting and polishing diamonds was invented in India, Ratnapariksha, a text dated to 6th century talks about diamond cutting and Al-Beruni speaks about the method of using lead plate for diamond polishing in the 11th century CE.[125]

- Etched Carnelian beads: are a type of ancient decorative beads made from carnelian with an etched design in white. They were made according to a technique of alkaline-etching developed by the Harappans during the 3rd millennium BCE and were widely disperced from China in the east to Greece in the west.[126][127][128]

- Glass blowing: Rudimentary form of glass blowing from Indian subcontinent is attested earlier than Western Asian counterparts(where it is attested not earlier than 1st century BCE) in the form of Indo-Pacific beads which uses glass blowing to make cavity before being subjected to tube drawn technique for bead making dated more than 2500 BP.[129][130] Beads are made by attaching molten glass gather to the end of a blowpipe, a bubble is then blown into the gather.[131] The glass blown vessels were rarely attested and were imported commodity in 1st millennium CE though.

- Iron pillar of Delhi: The world's first iron pillar was the Iron pillar of Delhi—erected at the time of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (375–413).[132] The pillar has attracted attention of archaeologists and materials scientists and has been called "a testament to the skill of ancient Indian blacksmiths" because of its high resistance to corrosion.[133]

- Lost-wax casting: Metal casting by the Indus Valley civilization began around 3500 BC in the Mohenjodaro area,[134] which produced one of the earliest known examples of lost-wax casting, an Indian bronze figurine named the "dancing girl" that dates back nearly 5,000 years to the Harappan period (c. 3300–1300 BC).[134][135] Other examples include the buffalo, bull and dog found at Mohenjodaro and Harappa,[136][135][137] two copper figures found at the Harappan site Lothal in the district of Ahmedabad of Gujarat,[134] and likely a covered cart with wheels missing and a complete cart with a driver found at Chanhudaro.[136][137]

- Lost wax Casting: It is the process by which a duplicate metal sculpture (often silver, gold, brass or bronze) is cast from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved by this method.The oldest known example of this technique is a 6,000-year old amulet from the Indus Valley Civilization.[2]

- Seamless celestial globe: Considered one of the most remarkable feats in metallurgy, it was invented in India in between 1589 and 1590 CE.[138][139] Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce metal globes without any seams, even with modern technology.[139]

- Stoneware: Earliest stonewares, predecessors of porcelain have been recorded at Indus Valley Civilization sites of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, they were used for making stoneware bangles.[140][141][142]

- Tube drawn technology: Indians used tube drawn technology for glass bead manufacturing which was first developed in the 2nd century BCE.[143][144][131]

- Tumble polishing: Indians innvoted polishing method in the 10th century BCE for mass production of polished stone beads.[145][124][146][147]

- Wootz steel: Wootz steel is an ultra-high carbon steel and the first form of crucible steel manufactured by the applications and use of nanomaterials in its microstructure and is characterised by its ultra-high carbon content exhibiting properties such as superplasticity and high impact hardness.[148] Archaeological and Tamil language literary evidence suggests that this manufacturing process was already in existence in South India well before the common era, with wootz steel exported from the Chera dynasty and called Seric Iron in Rome, and later known as Damascus steel in Europe.[149][150][151][152] Reproduction research is undertaken by scientists Dr. Oleg Sherby and Dr. Jeff Wadsworth and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have all attempted to create steels with characteristics similar to Wootz, but without success. J.D Verhoeven and Al Pendray attained some success in the reconstruction methods of production, proved the role of impurities of ore in the pattern creation, and reproduced Wootz steel with patterns microscopically and visually identical to one of the ancient blade patterns.[153]

- Bhāskara's wheel -Bhāskara's wheel was a hypothetical perpetual-motion machine design created around 1150 CE by the Indian mathematician Bhāskara II. The wheel consisted of curved or tilted spokes partially filled with mercury.[154] Once in motion, the mercury would flow from one side of the spoke to another, thus forcing the wheel to continue motion, in constant dynamic equilibrium.

Metrology

- Incense clock: The incense clock is a timekeeping device used to measure minutes, hours, or days, incense clocks were commonly used at homes and temples in dynastic times. Although popularly associated with China the incense clock is believed to have originated in India, at least in its fundamental form if not function.[155][156] Early incense clocks found in China between the 6th and 8th centuries CE—the period it appeared in China all seem to have Devanāgarī carvings on them instead of Chinese seal characters.[155][156] Incense itself was introduced to China from India in the early centuries CE, along with the spread of Buddhism by travelling monks.[157][158][159] Edward Schafer asserts that incense clocks were probably an Indian invention, transmitted to China, which explains the Devanāgarī inscriptions on early incense clocks found in China.[155] Silvio Bedini on the other hand asserts that incense clocks were derived in part from incense seals mentioned in Tantric Buddhist scriptures, which first came to light in China after those scriptures from India were translated into Chinese, but holds that the time-telling function of the seal was incorporated by the Chinese.[156]

- Standardisation: The oldest applications and evidence of standardisation come from the Indus Valley Civilisation in the 5th millennium BCE characterised by the existence of weights in various standards and categories as[160] well as the Indus merchants usage of a centralised weight and measure system. Small weights were used to measure luxury goods, and larger weights were used for buying bulkier items, such as food grains etc.[160] The weights and measures of the Indus civilisation also reached Persia and Central Asia, where they were further modified.[161]

A total of 558 weights were excavated from Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Chanhu-daro, not including defective weights. They did not find statistically significant differences between weights that were excavated from five different layers, each about 1.5 m in thickness. This was evidence that strong control existed for at least a 500-year period. The 13.7-g weight seems to be one of the units used in the Indus valley. The notation was based on the binary and decimal systems. 83% of the weights which were excavated from the above three cities were cubic, and 68% were made of chert.[162]

- Technical standards: Technical standards were being applied and used in the Indus Valley civilisation since the 5th millennium BCE to enable gauging devices to be effectively used in angular measurement and measurement in construction.[163] Uniform units of length were used in the planning and construction of towns such as Lothal, Surkotada, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Harappa, and Mohenjo-daro.[162] The weights and measures of the Indus civilisation also reached Persia and Central Asia, where they were further modified.[161]

Weapons

- Catapult by Ajatashatru in Magadha, India.[164]

- Mysorean rockets: One of the first iron-cased and metal-cylinder rockets were deployed by Tipu Sultan's army, ruler of the South Indian Kingdom of Mysore, and that of his father Hyder Ali, in the 1780s. He successfully used these iron-cased rockets against the larger forces of the British East India Company during the Anglo-Mysore Wars. The Mysore Rockets of this period were much more advanced than what the British had seen, chiefly because of the use of iron tubes for holding the propellant; this enabled higher thrust and longer range for the missile (up to 2 km range). After Tipu's eventual defeat in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War and the capture of the Mysore iron rockets, they were influential in British rocket development, inspiring the Congreve rocket, and were soon put into use in the Napoleonic Wars.[165]

- Scythed chariot by Ajatashatru in Magadha, India.[164]

Indigenisation and improvements

- Proto-writing: The Indus script is a symbol system that emerged during the end of the 4th millennium BC in the Indus Valley civilization.

- India ink: Known in Asia since the third millennia BCE, and used in India since at least the 4th century BCE.[166] Masi, an early ink in India was an admixture of several chemical components.,[166] with the carbon black from which India ink is produced obtained by burning bones, tar, pitch, and other substances.[167][168][169] Documents dating to the 3rd century CE, written in Kharosthi, with ink have been unearthed in East Turkestan, Xinjiang.[170] The practice of writing with ink and a sharp pointed needle was common in ancient South India.[171] Several Jain sutras in India were compiled in ink.[172]

Philosophy

- Catuskoti (Tetralemma): The four-cornered system of logical argumentation with a suite of four distinct functions that refers to a logical proposition P, with four possibilities that can arise. The tetralemma has many logico-epistemological applications and has been made ample use of by the Indian philosopher Nāgarjuna in the Madhyamaka school. The tetralemma also features prominently in the Greek skepticist school of Pyrrhonism, the teachings of which are based on Buddhism. The founder of the Pyrrhonist school lived in India for 18 months and likely learned the language, which allowed him to carry these teachings to Greece.[173]

Mathematics

| Number System | Numbers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Tamil | ೦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

| Gurmukhi | o | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Odia | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Bengali | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Assamese | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Devanagari | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Gujarati | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Tibetan | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ |

| Brahmi | ||||||||||

| Telugu | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Kannada | ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ |

| Malayalam | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

| Burmese | ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ |

| Khmer | ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ |

| Thai | ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ |

| Lao | ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ |

| Balinese | ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ |

| Santali | ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ |

| Javanese | ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ |

- Zero: Zero and its operation are first defined by (Hindu astronomer and mathematician) Brahmagupta in 628.[174] The Babylonians used a space, and later a zero glyph, in their written Sexagesimal system, to signify the 'absent',[175] the Olmecs used a positional zero glyph in their Vigesimal system, the Greeks, from Ptolemy's Almagest, in a Sexagesimal system. The Chinese used a blank, in the written form of their decimal Counting rods system. A dot, rather than a blank, was first seen to denote zero, in a decimal system, in the Bakhshali manuscript.[176] The usage of the zero in the Bakhshali manuscript was dated from between 3rd and 4th centuries, making it the earliest known usage of a written zero, in a decimal place value system.[177]

- Square root of 2 : early approximation is given in ancient Indian mathematical texts, the Sulbasutras (c. 800–200 BC), as follows: Increase the length [of the side] by its third and this third by its own fourth less the thirty-fourth part of that fourth.[178] That is,

- Quadratic equations: Indian mathematician Śrīdharācārya derived the quadratic formula used for solving quadratic equations.[179][180]

- Finite Difference Interpolation: The Indian mathematician Brahmagupta presented what is possibly the first instance[181][182] of finite difference interpolation around 665 CE.[183]

- Algebraic abbreviations: The mathematician Brahmagupta had begun using abbreviations for unknowns by the 7th century.[184] He employed abbreviations for multiple unknowns occurring in one complex problem.[184] Brahmagupta also used abbreviations for square roots and cube roots.[184]

- systematic generation of all permutations – The method goes back to Narayana Pandita in 14th century India, and has been rediscovered frequently.[185]

- Brahmagupta–Fibonacci identity,

- Brahmagupta formula

- Brahmagupta theorem

Discovered by the Indian mathematician, Brahmagupta (598–668 CE).[186][187][188][189]

- Combinatorics – the Bhagavati Sutra had the first mention of a combinatorics problem; the problem asked how many possible combinations of tastes were possible from selecting tastes in ones, twos, threes, etc. from a selection of six different tastes (sweet, pungent, astringent, sour, salt, and bitter). The Bhagavati is also the first text to mention the choose function.[190] In the second century BC, Pingala included an enumeration problem in the Chanda Sutra (also Chandahsutra) which asked how many ways a six-syllable meter could be made from short and long notes.[191][192] Pingala found the number of meters that had long notes and short notes; this is equivalent to finding the binomial coefficients.

- Jain theory of infinity : their texts define five different types of infinity: the infinite in one direction, the infinite in two directions, the infinite in area, the infinite everywhere, and the infinite perpetually.[193] and the Satkhandagama

- Chakravala method: The Chakravala method, a cyclic algorithm to solve indeterminate quadratic equations is commonly attributed to Bhāskara II, (c. 1114 – 1185 CE)[194][195][196] although some attribute it to Jayadeva (c. 950~1000 CE).[197] Jayadeva pointed out that Brahmagupta's approach to solving equations of this type would yield infinitely large number of solutions, to which he then described a general method of solving such equations.[198] Jayadeva's method was later refined by Bhāskara II in his Bijaganita treatise to be known as the Chakravala method, chakra (derived from cakraṃ चक्रं) meaning 'wheel' in Sanskrit, relevant to the cyclic nature of the algorithm.[198][199] With reference to the Chakravala method, E. O. Selenuis held that no European performances at the time of Bhāskara, nor much later, came up to its marvellous height of mathematical complexity.[194][198][200]

- Hindu number system: With decimal place-value and a symbol for zero, this system was the ancestor of the widely used Arabic numeral system. It was developed in the Indian subcontinent between the 1st and 6th centuries CE.[201][202]

- Fibonacci numbers: This sequence was first described by Virahanka (c. 700 CE), Gopāla (c. 1135), and Hemachandra (c. 1150),[203] as an outgrowth of the earlier writings on Sanskrit prosody by Pingala (c. 200 BCE).

- Law of signs in multiplication: The earliest use of notation for negative numbers, as subtrahend, is credited by scholars to the Chinese, dating back to the 2nd century BCE.[204] Like the Chinese, the Indians used negative numbers as subtrahend, but were the first to establish the "law of signs" with regards to the multiplication of positive and negative numbers, which did not appear in Chinese texts until 1299.[204] Indian mathematicians were aware of negative numbers by the 7th century,[204] and their role in mathematical problems of debt was understood.[205] Mostly consistent and correct rules for working with negative numbers were formulated,[206] and the diffusion of these rules led the Arab intermediaries to pass it on to Europe.,[205] for example (+)×(-)=(-),(-)×(-)=(+) etc.

- Bhāskara I's sine approximation formula

- Madhava series: The infinite series for π and for the trigonometric sine, cosine, and arctangent is now attributed to Madhava of Sangamagrama (c. 1340 – 1425) and his Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.[207][208] He made use of the series expansion of to obtain an infinite series expression for π.[207] Their rational approximation of the error for the finite sum of their series are of particular interest. They manipulated the error term to derive a faster converging series for π.[209] They used the improved series to derive a rational expression,[209] for π correct up to eleven decimal places, i.e. .[210][211] Madhava of Sangamagrama and his successors at the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics used geometric methods to derive large sum approximations for sine, cosine, and arctangent. They found a number of special cases of series later derived by Brook Taylor series. They also found the second-order Taylor approximations for these functions, and the third-order Taylor approximation for sine.[212][213][214]

- Madhava's correction terms; Madhava's correction term is a mathematical expression attributed to Madhava of Sangamagrama (c. 1340 – c. 1425), the founder of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, that can be used to give a better approximation to the value of the mathematical constant π (pi) than the partial sum approximation obtained by truncating the Madhava-Leibniz infinite series for π. The Madhava-Leibniz infinite series for π

- Pascal's triangle: Described in the 6th century CE by Varahamihira[215] and in the 10th century by Halayudha,[216] commenting on an obscure reference by Pingala (the author of an earlier work on prosody) to the "Meru-prastaara", or the "Staircase of Mount Meru", in relation to binomial coefficients. (It was also independently discovered in the 10th or 11th century in Persia and China.)

- Pell's equation, integral solution for: About a thousand years before Pell's time, Indian scholar Brahmagupta (598–668 CE) was able to find integral solutions to vargaprakṛiti (Pell's equation):[217][218] where N is a non-square integer, in his Brâhma-sphuṭa-siddhânta treatise.[219]

- Binary Logarithm; Earlier than Stifel, the 8th century Jain mathematician Virasena is credited with a precursor to the binary logarithm. Virasena's concept of ardhacheda has been defined as the number of times a given number can be divided evenly by two. This definition gives rise to a function that coincides with the binary logarithm on the powers of two,[220] but it is different for other integers, giving the 2-adic order rather than the logarithm.[221]

- Mean value theorem; A special case of this theorem for inverse interpolation of the sine was first described by Parameshvara (1380–1460), from the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics in India, in his commentaries on Govindasvāmi and Bhāskara II.[222]

- Sign convention: Symbols, signs and mathematical notation were employed in an early form in India by the 6th century when the mathematician-astronomer Aryabhata recommended the use of letters to represent unknown quantities.[184] By the 7th century Brahmagupta had already begun using abbreviations for unknowns, even for multiple unknowns occurring in one complex problem.[184] Brahmagupta also managed to use abbreviations for square roots and cube roots.[184] By the 7th century fractions were written in a manner similar to the modern times, except for the bar separating the numerator and the denominator.[184] A dot symbol for negative numbers was also employed.[184] The Bakhshali Manuscript displays a cross, much like the modern '+' sign, except that it symbolised subtraction when written just after the number affected.[184] The '=' sign for equality did not exist.[184] Indian mathematics was transmitted to the Islamic world where this notation was seldom accepted initially and the scribes continued to write mathematics in full and without symbols.[223]

- Modern elementary arithmetic: Modum indorum or the method of the Indians for arithmetic operations was popularised by Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Kindi by means of their respective works such as in Al-Khwarizmi's on the Calculation with Hindu Numerals (ca. 825), On the Use of the Indian Numerals (ca. 830)[224] as early as the 8th and 9th centuries.They, amongst other works, contributed to the diffusion of the Indian system of arithmetic in the Middle-East and the West.The significance of the development of the positional number system is described by the French mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace (1749–1827) who wrote:

"It is India that gave us the ingenuous method of expressing all numbers by the means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position, as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit, but its very simplicity, the great ease which it has lent to all computations, puts our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions, and we shall appreciate the grandeur of this achievement when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest minds produced by antiquity."

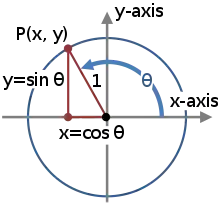

- Trigonometric functions : The trigonometric functions sine and versine originated in Indian astronomy along with the cosine and inversine , adapted from the full-chord Greek versions (to the modern half-chord versions). They were described in detail by Aryabhata in the late 5th century, but were likely developed earlier in the Siddhantas, astronomical treatises of the 3rd or 4th century.[225][226] Later, the 6th-century astronomer Varahamihira discovered a few basic trigonometric formulas and identities, such as sin^2(x) + cos^2(x) = 1.[215]

- Kuṭṭaka – The Kuṭṭaka algorithm has much similarity with and can be considered as a precursor of the modern day extended Euclidean algorithm. The latter algorithm is a procedure for finding integers x and y satisfying the condition ax + by = gcd(a, b).[227]

- Differential calculus- Preliminary concept of differentiation and the differential coefficient were known to bhaskaracharyaCooke, Roger (1997). The history of mathematics : a brief course. Internet Archive. New York : Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-18082-1.</ref>

- Formal systems: Panini is credited with the creation of the first Formal System in the world.

Mining

- Diamond mining and diamond tools: Diamonds were first recognised and mined in central India,[228][229][230] where significant alluvial deposits of the stone could then be found along the rivers Penner, Krishna and Godavari. It is unclear when diamonds were first mined in India, although estimated to be at least 5,000 years ago.[231] India remained the world's only source of diamonds until the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in the 18th century.[232][233][234] Golconda served as an important centre for diamonds in central India.[235] Diamonds then were exported to other parts of the world, including Europe.[235] Early references to diamonds in India come from Sanskrit texts.[236] The Arthashastra of Kautilya mentions diamond trade in India.[234] Buddhist works dating from the 4th century BCE mention it as a well-known and precious stone but don't mention the details of diamond cutting.[228] Another Indian description written at the beginning of the 3rd century describes strength, regularity, brilliance, ability to scratch metals, and good refractive properties as the desirable qualities of a diamond.[228] A Chinese work from the 3rd century BCE mentions: "Foreigners wear it [diamond] in the belief that it can ward off evil influences".[228] The Chinese, who did not find diamonds in their country, initially used diamonds as a "jade cutting knife" instead of as a jewel.[228]

- Zinc mining and medicinal zinc: Zinc was first smelted from zinc ore in India.[237] Zinc mines of Zawar, near Udaipur, Rajasthan, were active during early Christian era.[238][239] There are references of medicinal uses of zinc in the Charaka Samhita (300 BCE).[240] The Rasaratna Samuccaya which dates back to the Tantric period (c. 5th – 13th century CE) explains the existence of two types of ores for zinc metal, one of which is ideal for metal extraction while the other is used for medicinal purpose.[240][241] India was to melt the first derived from a long experience of the old alchemy zinc by the distillation process, an advanced technique. The ancient Persians had also tried to reduce zinc oxide in an open stove, but had failed. Zawar in Tiri valley of Rajasthan is the first known old zinc smelting site in the world. The distillation technique of zinc production dates back to the 12th century CE and is an important contribution of India in the world of science.

Innovations

- Flush deck: The flushed deck design was introduced with rice ships built in Bengal Subah, Mughal India (modern Bangladesh), resulting in hulls that were stronger and less prone to leak than the structurally weak hulls of stepped deck design.This was a key innovation in shipbuilding at the time.

- Iron working: Iron works were developed in India, around the same time as, but independently of, Anatolia and the Caucasus. Archaeological sites in India, such as Malhar, Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila and Lahuradewa in present-day Uttar Pradesh show iron implements in the period between 1800 BCE—1200 BCE.[242] Early iron objects found in India can be dated to 1400 BCE by employing the method of radiocarbon dating. Spikes, knives, daggers, arrow-heads, bowls, spoons, saucepans, axes, chisels, tongs, door fittings etc. ranging from 600 BCE to 200 BCE have been discovered from several archaeological sites of India.[243] Some scholars believe that by the early 13th century BCE, iron smelting was practised on a bigger scale in India, suggesting that the date the technology's inception may be placed earlier.[242] In Southern India (present day Mysore) iron appeared as early as 11th to 12th centuries BCE; these developments were too early for any significant close contact with the northwest of the country.[244] In the time of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (375–413 CE), corrosion-resistant iron was used to erect the Iron pillar of Delhi, which has withstood corrosion for over 1,600 years.[245]

Space

- Earth's orbit (Sidereal year): The Hindu cosmological time cycles explained in the Surya Siddhanta (c.600 CE), give the average length of the sidereal year (the length of the Earth's revolution around the Sun) as 365.2563627 days, which is only a negligible 1.4 seconds longer than the modern value of 365.256363004 days.[246] This calculation was the most accurate estimate for the length of the sidereal year anywhere in the world for over a thousand years.

- Periodicity of comets: Indian astronomers by the 6th century believed that comets were celestial bodies that re-appeared periodically. This was the view expressed in the 6th century by the astronomers Varahamihira and Bhadrabahu, and the 10th-century astronomer Bhattotpala listed the names and estimated periods of certain comets, but it is unfortunately not known how these figures were calculated or how accurate they were.[247]

Linguistics

- Formal grammar: In his treatise Astadhyayi, Panini gives formal production rules and definitions to describe the formal grammar of Sanskrit.[248] In formal language theory, a grammar (when the context is not given, often called a formal grammar for clarity) is a set of production rules for strings in a formal language. The rules describe how to form strings from the language's alphabet that are valid according to the language's syntax. A grammar does not describe the meaning of the strings or what can be done with them in whatever context—only their form.

Miscellaneous

- Punch (drink) a mixed drink containing fruits or fruit juice that can be both alcoholic and non-alcoholic originated in the Indian subcontinent before making its way into England by passage through the East India Company.[249] This beverage is very popular among the world with many varietal flavors and brands throughout the beverage industry.

Modern India

Communication

- Crystal detector by Jagadish Chandra Bose. Crystals were first used as radio wave detectors in 1894 by Bose in his microwave experiments. Bose first patented a crystal detector in 1901.[250][251][252]

- Horn antenna or microwave horn, One of the first horn antennas was constructed by Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1897.[253][254]

- Microwave Communication: The first public demonstration of microwave transmission was made by Jagadish Chandra Bose, in Calcutta, in 1895, two years before a similar demonstration by Marconi in England, and just a year after Oliver Lodge's commemorative lecture on Radio communication, following Hertz's death. Bose's revolutionary demonstration forms the foundation of the technology used in mobile telephony, radars, satellite communication, radios, television broadcast, WiFi, remote controls and countless other applications.[255][256]

- Low Mobility Large cell (LMLC), is a feature of 5G and is designed to enhance the signal transmission range of a basestation several times, helping service providers cost-effectively expand coverage in rural areas.[257]

Computers and programming languages

- J Sharp: Visual J# programming language was a transitional language for programmers of Java and Visual J++ languages, so they could use their existing knowledge and applications on .NET Framework. It was developed by the Hyderabad-based Microsoft India Development Center at HITEC City in India.[258][259]

- Julia is a high-level, dynamic programming language. Its features are well suited for numerical analysis and computational science. Viral B. Shah an Indian computer scientist contributed to the development of the language in Bangalore while also actively involved in the initial design of the Aadhaar project in India using India Stack.[260]

- Kojo: Kojo is a programming language and integrated development environment (IDE) for computer programming and learning. Kojo is an open-source software. It was created, and is actively developed, by Lalit Pant, a computer programmer and teacher living in Dehradun, India.[261][262]

- RISC-V ISA (microprocessor) implementations:

- SHAKTI – Open Source, Bluespec System Verilog definitions, for FinFET implementations of the ISA, have been created at IIT Madras, and are hosted on GitLab.[263]

- VEGA Microprocessors: India's first indigenous 64-bit, superscalar, out-of-order, multi-core RISC-V Processor design, developed by C-DAC.[264]

Construction, civil engineering and architecture

- BharatNet(National Optical Fibre Network) is establishment, management, and operation of the National Optical Fibre Network as an Infrastructure to provide a minimum of 100 Mbit/s broadband connectivity to all rural and remote areas. BBNL was established in 2012 to lay the optical fiber.

- Rib & spine/Spine & Wing technique, NHAI has developed a flyover design which allows to save cost, time, minimum material usage and allows light under the flyover using the same technique.

- Dedicated Freight Corridors, is a new kind of railway lines that solely serve high-speed electric freight trains, thus making the freight service in India faster and more efficient.

- Genome Valley is world's first organized cluster for Life Sciences R&D and Clean Manufacturing activities, with Industrial / Knowledge Parks, Special Economic Zones (SEZs), Multi-tenanted dry and wet laboratories and incubation facilities.

- (I)-TM Tunneling technique:(I)-TM as Himalayan tunnelling method for tunnelling through the Himalayan geology to build tunnels in Jammu and Kashmir. Engineers decided to provide rigid supports using 'ISHB' as against the lattice girder method used in the New Austrian Tunnelling Method.ISHB uses nine-metre pipes in the mountains. It is called pipe roofing. Engineers made an umbrella using these perforated poles and filled them with PU grout.[265][266]

- KOLOS: KOLOS is a wave-dissipating concrete block intended to protect coastal structures like seawalls and breakwaters from the ocean waves. These blocks were first developed in India by Navayuga Engineering Company(NEC)[267] and were first adopted for the breakwaters of the Krishnapatnam Port

- Plastic road are made entirely of plastic or of composites of plastic with other materials. Plastic roads are different from standard roads in the respect that standard roads are made from asphalt concrete, which consists of mineral aggregates and asphalt. Most plastic roads sequester plastic waste within the asphalt as an aggregate. Plastic roads first developed by Rajagopalan Vasudevan in 2001[268][269][270]

- Regional Rapid Transit System(RRTS) is a new kind of elevated transit system, which can provide connectivity to long distances(60km to 80kms) in a short time for large megapolis. RRTS provides semi-high speeds which ranges from 100 km/hr to 160km/hr.

- Chenab Bridge is world's highest rail bridge and world's first blast-proof steel bridge.The bridge is built using 63mm-thick special blast-proof steel.[271]

- Soil Health Card under the scheme, the government plans to issue soil cards to farmers which will carry crop-wise recommendations of nutrients and fertilisers required for the individual farms to help farmers to improve productivity through judicious use of inputs. All soil samples are to be tested in various soil testing labs across the country.

Finance and banking

- Direct Benefit Transfer, This program aims to transfer subsidies directly to the people through their bank accounts. It is hoped that crediting subsidies into bank accounts will reduce leakages, delays, etc.

- Digital Banking Unit(DBU) is a specialised fixed point business unit/hub housing certain minimum digital infrastructure for delivering digital banking products and services as well as servicing existing financial products & services digitally, in both self-service and assisted mode.[272]

- Payments bank is an Indian new model of banks conceptualised by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) without issuing credit.

- Small Finance Bank are a type of niche banks in India. Banks with a small finance bank (SFB) license can provide basic banking service of acceptance of deposits and lending. The aim behind these is to provide financial inclusion to sections of the economy not being served by other banks.

- Payment Soundbox comes with a portable speaker that gives you an instant audio confirmation on receiving digital payments in your preferred regional language. This ensures that you do not miss even a single payment during peak times at work.

- Micro Finance Institutions(MFI) is an organization that offers financial services to low income populations.

Genetics

- Amrapali mango is a named mango cultivar introduced in 1971 by Dr. Pijush Kanti Majumdar at the Indian Agriculture Research Institute in Delhi.

- Mynvax is world's first "warm" COVID-19 vaccine, developed by IISc, capable of withstanding 37C for a month and neutralise all coronavirus variants of concern.[273]

- ZyCoV-D vaccine, World's First DNA Based Covid-19 Vaccine. [274]

Metallurgy , Manufacturing and Industrial

- 2G-Ethanol technology, which produces ethanol from agricultural residue feedstock, has the potential to significantly reduce emissions from the transportation and agricultural sectors in India.The IP belongs to Praj Industries.

- Carbon Nitride Solar reactor for hydrogen production, In September 2021, A team from the Institute of Nano Science and Technology (INST), Mohali, has fabricated a prototype reactor which operates under natural sunlight to produce hydrogen at a scale of around 6.1 litres in eight hours. They have used an earth-abundant chemical called carbon nitrides as a catalyst for the purpose.[275][276]

- High ash coal gasification(Coal to Methanol), The Central Government gave the country world's first 'coal to methanol' (CTM) plant built by the Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL). The plant was inaugurated in BHEL's Hyderabad unit, The pilot project is the first that uses the gasification method for converting high-ash coal into methanol. Handling of high ash and heat required to melt this high amount of ash is a challenge in the case of Indian coal, which generally has high ash content. Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited has developed the fluidized bed gasification technology suitable for high ash Indian coals to produce syngas and then convert syngas to methanol with 99% purity.[277]

- CBM in Blast Furnace, Tata Steel has initiated the trial for continuous injection of Coal Bed Methane (CBM) gas in one of the Blast Furnaces at its Jamshedpur Works, making it the first such instance in the world where a steel company has used CBM as injectant. This process is expected to reduce coke rate by 10 kg/thm, which will be equivalent to reducing 33 kg of CO2 per tonne of crude steel.[278]

- Controlled Shunt Reactor, In 2002 Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited has successfully developed a first-of-its-kind in the world device for improving power transfer capability and reducing transmission losses in the country's highest rating (400 kV) transmission lines.The device is called Controlled Shunt Reactor. [279][280]

- DMR grade steels for several high-technology applications, such as military hardware and aerospace, need to possess ultrahigh strength (UHS; minimum yield strength of 1380 MPa (200 ksi)) coupled with high fracture toughness in order to meet the requirement of minimum weight while ensuring high reliability.

- Fortified Cabin, is a car designing technique by TATA Motors such that the high-strength steel structure absorbs impact energy and protects the passenger during an unfortunate collision.Tata Nexon has the fortified cabin design for achieving full 5 star safety ratings.

- HIsarna a new process for production of steel, one it says "results in enormous efficiency gains" and reduces energy use and carbon dioxide emissions by a fifth of that in the conventional blast furnace route.It's IP belongs to TATA Steel.

- Sorption Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming (SESMR), In April 2022, the scientists from CSIR-Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (CSIR-IICT), Hyderabad developed a fluidized bed reactor (FBR) facility in Hyderabad to perform sorption enhanced steam methane reforming (SESMR) to achieve clean hydrogen in its purest form. The team of scientists have designed a hybrid material to simulate capturing carbon dioxide in-situ (onsite) and converting it into clean hydrogen from non-fuel grade bioethanol.[281]

- Spray-drying Buffalo milk, The collective consensus of dairy experts worldwide was that buffalo milk could not be spray-dried due to its high fat content. Harichand Megha Dalaya & his invention of the spray dry equipment, led to the world's first buffalo milk spray-dryer, at Amul Dairy in Gujarat.

- Jackal steel is an advanced grade high strength low alloy steel, The technology of Jackal steel has been passed on to Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL) and MIDHANI for its bulk production.

- High-Rise Pantograph, The new-design world record pantograph, developed completely in-house for use in DFC & other Freight routes with height of 7.5 meters.[282]

- 1200 kV UHDVC Transformer, world's first ultra high voltage ac 1200kV transformer through in-house R&D by BHEL in 2011.[283]

- Commercial CCU plant: Tuticorin Alkali Chemicals and Fertilizers Limited (TFL) partnered with Carbon Clean to create the world’s first fully commercial CCU plant. The 10MW facility captures coal-fired boiler flue gas and uses it to deliver industrial quality CO2.The 10MW facility captures coal-fired boiler flue gas and uses it to deliver industrial quality CO2.[284]The technology has been developed by Carbon Clean Solutions, headquartered in London – a start-up by two Indian engineers focusing on carbon dioxide separation technology.There are many chemicals exported out of India where CO2 is the raw material.[285]

- Triple stack container freight train[286]: In order to ensure new streams of traffic and commodities and to bring about a modal shift, the DFC is undertaking trials for running smaller than usual containers, known as dwarf containers (where the container height is lower by 660 mm than normal containers), in triple-stack formation to further improve the profitability of train operations. It may be possible to run these as double-stack on conventional routes and triple-stack on routes with high-rise OHE, once the trials are successfully completed.[287]

Metrology

- Crescograph: The crescograph, a device for measuring growth in plants, was invented in the early 20th century by the Bengali scientist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose.[288][289]

- Shearing Interferometer: Invented by M.V.R.K. Murty, a type of Lateral Shearing Interferometer utilises a laser source for measuring refractive index.[290][291]

Science and technology

- Bipyrazole Organic Crystals, the piezoelectric molecules developed by IISER scientists recombine following mechanical fracture without any external intervention, autonomously self-healing in milliseconds with crystallographic precision.[292]

- Single-crystalline Scandium Nitride, that has the ability to convert infrared light into energy, Scientists based in Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR), Bengaluru have discovered a novel material that can emit, detect, and modulate infrared light with high efficiency making it useful for solar and thermal energy harvesting and for optical communication devices.[293][294]

- e-mode HEMT, In 2019 scientists from Bangalore have developed a highly reliable, High Electron Mobility Transistor (HEMTs) that is a normally OFF device and can switch currents up to 4A and operates at 600V. This first-ever indigenous HEMT device made from gallium nitride (GaN). Such transistors are called e-mode or enhancement mode transistors.[295][296]

- Nano Urea, the size of one nano urea liquid particle is 30 nanometre and compared to the conventional granular urea it has about 10,000 times more surface area to volume size. Due to the ultra-small size and surface properties, the nano urea liquid gets absorbed by plants more effectively when sprayed on their leaves.Ramesh Raliya of IFFCO is the inventor of nano urea.

- Locomotive with Regenerative braking, BHEL has developed world's first ever DC electric locomotive with a regenerative braking system through its in-house R&D centre, First proposed by the Railway Ministry, the concept involving the energy-efficient regeneration system was put into shape by BHEL in a 5,000 HP WAG-7 electric locomotive.[297]

- In2Se3 transistor developed by the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering (CeNSE), a ferroelectric channel semiconductor FET, i.e., FeS-FET, whose gate-triggered and polarization-induced resistive switching is then exploited to mimic an artificial synapse.

- Indian Ocean Dipole is an unusual pattern in the ocean-atmosphere system of the equatorial Indian Ocean that influences the monsoon and can offset the adverse impact of El Nino. It is typically characterized by cooler than normal eastern equatorial Indian Ocean and warmer than normal west and unusual equatorial easterly winds. It was discovered in Centre for Atmospheric And Oceanic Sciences, IISc. team led by NH Saji in 1999.[298]

- Wireless Railway Signaling System: Nokia partnered with Alstom to implement the 4.9G/LTE private wireless network to support the ETCS L2 signalling in Regional Rapid Transit System. This is a “world-first application” of an LTE network that is being used along with ETCS Level 2 signaling to provide high-speed, high-reliability commuter service. In addition, ETCS Level 2-based system allows trains to report their precise location in real-time.[299]

- Solution combustion synthesis (SCS) was accidentally discovered in 1988 at Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, India. SCS involves an exothermic redox chemical reaction between an oxidizer like metal nitrate and a fuel in an aqueous medium.[300]

- Three-stage nuclear power programme was formulated by Homi Bhabha, the well-known physicist, in the 1950s to secure the country's long term energy independence, through the use of uranium and thorium reserves found in the monazite sands of coastal regions of South India.

- Rare earth free motor, deep-tech startup Chara has built scalable, cloud-controlled electric vehicle motors free of toxic rare-earth metals, thus cutting a massive dependency on imports to accelerate electric mobility in India.[301]

Weapon systems

- ASMI, Indian submachine gun which means "pride, self respect and hard work", was first showcased in January 2021, and developed over the course of four months by Lieutenant Colonel Prasad Bansod. 3D printing was utilized to make parts of the gun[302][303]

- ATAGS, Bharat Forge and DRDO has developed world's first electric artillery gun[304]

- Critical Situation Response Vehicle(CSRV), Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) has made and inducted a bomb/bulletproof armoured vehicle. The latest all-terrain highly sophisticated vehicle 'CSRV' has given a shot in the arm to the Central Reserve Police Force engaged in counter-terror operations.

- E-bomb, Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has been developing an e-bomb which will emit electromagnetic shock waves that destroy electronic circuits and communication networks of enemy force.[305] The tow bodies in Lakshya-2 Weapon Delivery Configuration carry High Energy Weapon Payload.[306]

Indigenisation and improvements

- CNG car/vehicle, Bajaj Auto launched the first 'commercial' lot of its CNG (Compressed Natural Gas) autorickshaws in Delhi on 29 May 2000.

- Digital Rupee (e₹) or eINR or E-Rupee is a tokenised digital version of the Indian Rupee, to be issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as a central bank digital currency (CBDC). Digital Rupee is using blockchain distributed-ledger technology.Digital rupee users to hit 50,000 by Jan-end on better acceptance. [307]

- Electrified Flex-fuel ,World's first Electrified Flex-fuel vehicle was unveiled by Toyota in India, an Electrified Flex Fuel Vehicle has both a flex-fuel engine as well as an electric powertrain, thereby offering higher use of ethanol combined with better fuel efficiencies.[308]

- Unified Payments Interface is an instant real-time payment system developed by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) facilitating person-to-merchant (P2M) transactions through inter-bank peer-to-peer (P2P) mechanism. UPI doesn't needs Internet connection for financial transactions and card-less ATM transactions can also occur using UPI.UPI is not an alternative to Wallet, but more kind of solution to money printing problem.

Mathematics

- AKS primality test: The AKS primality test is a deterministic primality-proving algorithm created and published by three Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur computer scientists, Manindra Agrawal, Neeraj Kayal, and Nitin Saxena on 6 August 2002 in a paper titled PRIMES is in P.[309][310] Commenting on the impact of this discovery, Paul Leyland noted: "One reason for the excitement within the mathematical community is not only does this algorithm settle a long-standing problem, it also does so in a brilliantly simple manner. Everyone is now wondering what else has been similarly overlooked".[310][311]

- Seshadri constant: In algebraic geometry, a Seshadri constant is an invariant of an ample line bundle L at a point P on an algebraic variety.The name is in honour of the Indian mathematician C. S. Seshadri.

- Basu's theorem: The Basu's theorem, a result of Debabrata Basu (1955) states that any complete sufficient statistic is independent of any ancillary statistic.[312][313]

- Kosambi-Karhunen-Loève theorem (also known as the Karhunen–Loève theorem) The Kosambi-Karhunen-Loève theorem is a representation of a stochastic process as an infinite linear combination of orthogonal functions, analogous to a Fourier series representation of a function on a bounded interval. Stochastic processes given by infinite series of this form were first[314] considered by Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi.[315]

- Magical Indian Math discovery: Numbers 495 and 6174. The Indian mathematician Dattaraya Ramchandra Kaprekar discovered the number 6174 is reached after repeatedly subtracting the smallest number from the largest number that can be formed from any four digits not all the same. The number 495 is similarly reached for three digits number.

- Kosaraju's algorithm is a linear time algorithm to find the strongly connected components of a directed graph. Aho, Hopcroft and Ullman credit it to S. Rao Kosaraju and Micha Sharir. Kosaraju suggested it in 1978.

- Ramanujan theta function, Ramanujan prime, Ramanujan summation, Ramanujan graph and Ramanujan's sum: Discovered by the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan in the early 20th century.[316]

- Shrikhande graph: Graph invented by the Indian mathematician S.S. Shrikhande in 1959.

Sciences

- Gravity: Aryabhata first identified the force to explain why objects do not spin out when the earth rotates, Brahmagupta proposed (c. 628 CE) "bodies fall towards the earth as it is in the nature of the earth to attract bodies, just as it is in the nature of water to flow", using the term gurutvākarṣaṇ for this phenomenon.[317][318][319]

- Ammonium nitrite, synthesis in pure form: Prafulla Chandra Roy synthesised NH4NO2 in its pure form, and became the first scientist to have done so.[320] Prior to Ray's synthesis of Ammonium nitrite it was thought that the compound undergoes rapid thermal decomposition releasing nitrogen and water in the process.[320]

- Ashtekar variables: In theoretical physics, Ashtekar (new) variables, named after Abhay Ashtekar who invented them, represent an unusual way to rewrite the metric on the three-dimensional spatial slices in terms of a SU(2) gauge field and its complementary variable. Ashtekar variables are the key building block of loop quantum gravity.

- Bhatnagar-Mathur Magnetic Interference Balance: Invented jointly by Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar and K.N. Mathur in 1928, the so-called 'Bhatnagar-Mathur Magnetic Interference Balance' was a modern instrument used for measuring various magnetic properties.[321] The first appearance of this instrument in Europe was at a Royal Society exhibition in London, where it was later marketed by British firm Messers Adam Hilger and Co, London.[321]

- Bhabha scattering: In 1935, Indian nuclear physicist Homi J. Bhabha published a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series A, in which he performed the first calculation to determine the cross section of electron-positron scattering.[322] Electron-positron scattering was later named Bhabha scattering, in honour of his contributions in the field.[322]

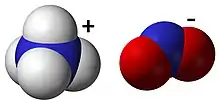

- Bose–Einstein statistics, condensate: On 4 June 1924 the Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose mailed a short manuscript to Albert Einstein entitled Planck's Law and the Light Quantum Hypothesis seeking Einstein's influence to get it published after it was rejected by the prestigious journal Philosophical Magazine.[323] The paper introduced what is today called Bose statistics, which showed how it could be used to derive the Planck blackbody spectrum from the assumption that light was made of photons.[323][324] Einstein, recognizing the importance of the paper translated it into German himself and submitted it on Bose's behalf to the prestigious Zeitschrift für Physik.[323][324] Einstein later applied Bose's principles on particles with mass and quickly predicted the Bose-Einstein condensate.[324][325]

- Boson: The name boson was coined by Paul Dirac[326] to commemorate the contribution of the Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose.[327][328] In quantum mechanics, a boson (/ˈboʊsɒn/,[329] /ˈboʊzɒn/[330]) is a particle that follows Bose–Einstein statistics. Bosons make up one of the two classes of particles, the other being fermions.[331]

- Braunstein-Ghosh-Severini Entropy: This modelling of entropy using network theory is used in the analysis of quantum gravity and is named after Sibasish Ghosh and his teammates, Samuel L. Braunstein and Simone Severini.

- Chandrasekhar limit and Chandrasekhar number: Discovered by and named after Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983 for his work on stellar structure and stellar evolution.[332] Subrrahmanyan Chandrasekhar discovered the calculation used to determine the future of what would happen to a dying star. If the star's mass is less than the Chandrasekhar Limit it will shrink to become a white dwarf, and if it is great the star will explode, becoming a supernova

- Galena, applied use in electronics of: Bengali scientist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose effectively used Galena crystals for constructing radio receivers.[333] The Galena receivers of Bose were used to receive signals consisting of shortwave, white light and ultraviolet light.[333] In 1904 Bose patented the use of Galena Detector which he called Point Contact Diode using Galena.[334]