Lugalbanda

Lugalbanda[lower-alpha 1] was a deified Sumerian king of Uruk who, according to various sources of Mesopotamian literature, was the father of Gilgamesh. Early sources mention his consort Ninsun and his heroic deeds in an expedition to Aratta by King Enmerkar.

| Lugalbanda 𒈗𒌉𒁕 | |

|---|---|

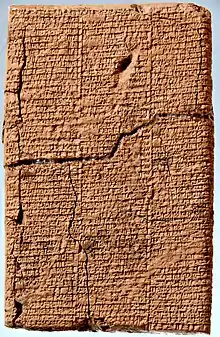

The story of Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave, Old-Babylonian period, from southern Iraq. Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan. | |

| King of the First dynasty of Uruk | |

| Reign | c. 3400-3100 BC (Late Uruk Period) |

| Predecessor | Enmerkar |

| Successor | Dumuzid, the Fisherman |

| Dynasty | Uruk I |

Lugalbanda is listed in the Sumerian King List as the second king of Uruk, saying he ruled for 1200 years, and providing him with the epithet of the Shepherd.[3] Lugalbanda's historicity is uncertain among scholars. Attempts to date him in the ED II period are based on an amalgamation of data from the epic traditions of the 2nd millennium with unclear archaeological observations.[4]

Mythology

Lugalbanda appears in Sumerian literary sources as early as the mid-3rd millennium, as attested by the incomplete mythological text Lugalbanda and Ninsuna, found in Abu Salabikh, that describes a romantic relationship between Lugalbanda and Ninsun.[5] In the earliest god-lists from Fara, his name appears separate and in a much lower ranking than the goddess; however, in later traditions until the Seleucid period, his name is often listed along with his consort Ninsun.[6]

There's evidence suggesting the worship of Lugalbanda as a deity originating from the Ur III period, as attested in tablets from Nippur, Ur, Umma and Puzrish-Dagan.[7] In the Old Babylonian period Sin-kashid of Uruk is known to have built a temple called É-KI.KAL dedicated to Lugalbanda and Ninsun, and to have assigned his daughter Niši-īnī-šu as the eresh-dingir priestess of Lugalbanda.[8]

At the same time, Lugalbanda would prominently feature as the hero of two Sumerian stories dated to the Third Dynasty of Ur, called by scholars Lugalbanda I (Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave) and Lugalbanda II (Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird). Both are known only in later versions, although there is an Ur III fragment that is quite different from either 18th century version[9]

These tales are part of a series of stories that describe the conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Uruk, and Ensuhkeshdanna, lord of Aratta, presumably in the Iranian highlands. In these two stories, Lugalbanda is a soldier in the army of Enmerkar, whose name also appears in the Sumerian King List as the first king of Uruk and predecessor of Lugalbanda. The extant fragments make no reference to Lugalbanda's succession as king following Enmerkar.[10]

In royal hymns of the Ur III period, Ur-Nammu of Ur and his son Shulgi describe Lugalbanda and Ninsun as their holy parents, and in the same context call themselves the brother of Gilgamesh.[11] Sin-Kashid of Uruk also refers to Lugalbanda and Ninsun as his divine parents, and names Lugalbanda as his god.[12]

In the Epic of Gilgamesh and in earlier Sumerian stories about the hero, Gilgamesh calls himself the son of Lugalbanda and Ninsun. In the Gilgamesh and Huwawa poem, the king consistently uses the assertive phrase: “By the life of my own mother Ninsun and of my father, holy Lugalbanda!”.[13][14] In Akkadian versions of the epic, Gilgamesh also refers to Lugalbanda as his personal god, and in one episode presents the oil filled horns of the defeated Bull of Heaven "for the anointing of his god Lugalbanda".[15]

See also

References

- "Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary Project". Archived from the original on 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- Vanstiphout, H. (2002) “Sanctus Lugalbanda” in Riches Hidden in Secret Places, T. Abusch (ed.), Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, p. 260; The name has no such connotations of 'crown prince'.

- English translation of Sumerian King List in The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Lugalbanda, Reallexikon der Assyriologie 7, p. 117.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1989) “Lugalbanda and Ninsuna”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 69-86

- Exceptions exist. For a full summary of the god-list references refer to Reallexikon der Assyriologie 7, p. 118.

- Reallexikon der Assyriologie 7, pp. 119–120. Nippur tablets indicate that all Ur III kings have made offerings to the deity Lugalbanda

- Reallexikon der Assyriologie 7, p. 120

- Michalowski, P. (2009) “Maybe Epic: The Origins and Reception of Sumerian Heroic Poetry” in Epic and History, D. Konstans and K. Raaflaub (eds.), Oxford: Blackwells. p. 13 and n.8; Tablet 6N-T638; as of March 2011 tablet awaits publication.

- For a detailed treatment of Enmerkar and Lugalbanda stories see: Vanstiphout, H. (2003). Epics of Sumerian Kings, Atlanta: SBL. ISBN 1-58983-083-0

- Reallexikon der Assyriologie 7, p. 131. See also Ur-Namma hymns and Shulgi hymns

- Sjöberg, Äke W. (1972) “Die Göttliche Abstammung der sumerisch-babylonischen Herrscher,” Orientalia Suecana 21, p. 98

- Ninsumun is another name for Ninsun. Both names Lugalbanda and Ninsun are written with divine determinatives. For two separate Sumerian versions of Gilgamesh and Huwawa see ETCSL.

- For a discussion of parentage of Gilgamesh and further references see: George, Andrew (2003), Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-814922-0, p. 107 ff.

- George, p. 629.

Scholarly literature

- Alster, Bendt. "Lugalbanda and the early epic tradition in Mesopotamia." In Lingering over Words: Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Literature in Honor of William L. Moran, pp. 59–72. Brill, 1990.

- Alster, Bendt. "Demons in the Conclusion of Lugalbanda in Hurrumkurra." Iraq 67, no. 2 (2005): 61–71.

- Falkowitz, Robert S. "Notes on" Lugalbanda and Enmerkar"." Journal of the American Oriental Society 103, no. 1 (1983): 103-114.

- Larson, Jennifer. "Lugalbanda and Hermes." Classical Philology 100, no. 1 (2005): 1-16.

- Noegel, Scott B. "Mesopotamian epic." A Companion to Ancient Epic (2005): 233–245.

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg.webp)