Manchu language

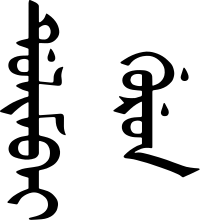

Manchu (Manchu:ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ

ᡤᡳᠰᡠᠨ, Romanization: manju gisun) is a critically endangered East Asian Tungusic language native to the historical region of Manchuria in Northeast China.[6] As the traditional native language of the Manchus, it was one of the official languages of the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) of China, although today the vast majority of Manchus speak only Mandarin Chinese. Several thousand can speak Manchu as a second language through governmental primary education or free classes for adults in classrooms or online.[3][4][5]

| Manchu | |

|---|---|

| ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᡳᠰᡠᠨ | |

Manju gisun written in Manchu script | |

| Native to | China |

| Region | Manchuria |

| Ethnicity | Manchus |

Native speakers | 20 native speakers[1] (2007)[2] Thousands of second language speakers[3][4][5] |

| Manchu alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mnc |

| ISO 639-3 | mnc |

| Glottolog | manc1252 |

| ELP | Manchu |

Manchu is classified as "Critically Endangered" by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The Manchu language enjoys high historical value for historians of China, especially for the Qing dynasty. Manchu-language texts supply information that is unavailable in Chinese, and when both Manchu and Chinese versions of a given text exist they provide controls for understanding the Chinese.[7]

Like most Siberian languages, Manchu is an agglutinative language that demonstrates limited vowel harmony. It has been demonstrated that it is derived mainly from the Jurchen language though there are many loan words from Mongolian and Chinese. Its script is vertically written and taken from the Mongolian script (which in turn derives from Aramaic via Uyghur and Sogdian). Although Manchu does not have the kind of grammatical gender found in most European languages, some gendered words in Manchu are distinguished by different stem vowels (vowel inflection), as in ama, 'father', and eme, 'mother'.

Names

The Qing dynasty used various Mandarin Chinese expressions to refer to the Manchu language, such as "Qingwen" (清文)[8] and "Qingyu" (清語) ("Qing language"). The term "national" was also applied to writing in Manchu, as in Guowen (國文), in addition to Guoyu (國語) ("national language"),[9] which was used by previous non-Han dynasties to refer to their languages and, in modern times, to the Standard Chinese language.[10] In the Manchu-language version of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the term "Chinese language" (Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to all three Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, not just one language.[11]

History and significance

Historical linguistics

Manchu is southern Tungusic. Whilst Northern Tungus languages such as Evenki retain traditional structure, the Chinese language is a source of major influence upon Manchu, altering its form and vocabulary.[12]

In 1635 Hong Taiji renamed the Jurchen people and Jurchen language as 'Manchu'. The Jurchen are the ancestors of the Manchu and ruled over the later Jin dynasty (1115–1234).

Decline of use

Manchu began as a primary language of the Qing dynasty Imperial court, but as Manchu officials became increasingly sinicized many started losing the language. Trying to preserve the Manchu identity, the imperial government instituted Manchu language classes and examinations for the bannermen, offering rewards to those who excelled in the language. Chinese classics and fiction were translated into Manchu and a body of Manchu literature accumulated.[13] As the Yongzheng Emperor (reigned 1722–1735) explained,

"If some special encouragement … is not offered, the ancestral language will not be passed on and learned."[14]

Still, the use of the language among the bannermen declined throughout the 1700s. Historical records report that as early as 1776, the Qianlong Emperor was shocked to see a high Manchu official, Guo'ermin, not understand what the emperor was telling him in Manchu, despite coming from the Manchu stronghold of Shengjing (now Shenyang).[15] By the 19th century even the imperial court had lost fluency in the language. The Jiaqing Emperor (reigned 1796–1820) complained that his officials were not proficient at understanding or writing Manchu.[14]

By the end of the 19th century the language had declined to such an extent that even at the office of the Shengjing general the only documents written in Manchu (rather than Chinese) would be the memorials wishing the emperor long life; during the same period the archives of the Hulan banner detachment in Heilongjiang show that only 1% of the bannermen could read Manchu and no more than 0.2% could speak it.[14] Nonetheless as late as 1906–1907 Qing education and military officials insisted that schools teach Manchu language and that the officials testing soldiers' marksmanship continue to conduct an oral examination in Manchu.[16]

The use of the language for the official documents declined throughout Qing history as well. In particular, at the beginning of the dynasty, some documents on sensitive political and military issues were submitted in Manchu but not in Chinese.[17] Later on, some Imperial records in Manchu continued to be produced until the last years of the dynasty.[14] In 1912 the Qing was overthrown, most Manchus could not speak their language, and the Beijing dialect replaced Manchu.[18]

Use of Manchu

A large number of Manchu documents remain in the archives, important for the study of Qing-era China. Today written Manchu can still be seen on architecture inside the Forbidden City, whose historical signs are written in both Chinese and Manchu. Another limited use of the language was for voice commands in the Qing army, attested as late as 1878.[14]

Bilingual Chinese-Manchu inscriptions appeared on many things.[19][20]

Manchu studies during the Qing dynasty

A Jiangsu Han Chinese named Shen Qiliang wrote books on Manchu grammar, including Guide to Qing Books (清書指南; Manju bithe jy nan) and Great Qing Encyclopedia (大清全書; Daicing gurun-i yooni bithe). His father was a naval officer for the Qing and his grandfather was an official of the Ming dynasty before rebels murdered him. Shen Qiliang himself fought against the Three Feudatories as part of the Qing army. He then started learning Manchu and writing books on Manchu grammar from Bordered Yellow Manchu Bannermen in 1677 after moving to Beijing. He translated the Hundred Family Names and Thousand Character Classic into Manchu and spent 25 years on the Manchu language. Shen wrote: "I am a Han. But all my life I have made a hobby of Manchu." Shen didn't have to learn Manchu as part of his job because he was never an official so he seems to have studied it voluntarily. Most Han people were not interested in learning non-Han languages so it is not known why Shen was doing it.[21]

A Hangzhou Han Chinese, Chen Mingyuan, helped edit the book Introduction to the Qing language (清文啟蒙; Cing wen ki meng bithe), which was co-written by a Manchu named Uge. Uge gave private Manchu language classes, which were attended by his friend Chen. Chen arranged for its printing.[22]

Hanlin

Han Chinese at the Hanlin Academy studied the Manchu language in the Qing. The Han Chinese Hanlin graduate Qi Yunshi knew the Manchu language and wrote a book in Chinese on the frontier regions of China by translating and using the Manchu-language sources in the Grand Secretariat's archives.[23] Hanlin Academy in 1740 expelled the Han Chinese Yuan Mei for not succeeding in his Manchus studies. Injišan, and Ortai, both Manchus, funded his work.[24] The Han Chinese Yan Changming had the ability to read Tibetan, Oirat, and Mongolian.[25] Han Chinese officials learned languages on the frontier regions and Manchu in order to be able to write and compile their writings on the region.[26]

A Manchu-language course over three years was required for the highest ranking Han degree holders from Hanlin but not all Han literati were required to study Manchu.[27] Towards the end of the Qing it was pointed out that a lot of Bannermen themselves did not know Manchu anymore and that Manchu was not able to be forced upon the people and minister of the country at the beginning of the Qing dynasty.[28]

Translation between Chinese and Manchu

Chinese fiction books were translated into Manchu.[29] Bannermen wrote fiction in the Chinese language.[30] Huang Taiji had Chinese books translated into Manchu.[31][32] Han Chinese and Manchus helped Jesuits write and translate books into Manchu and Chinese.[33] Manchu books were published in Beijing.[34]

The Qianlong Emperor commissioned projects such as new Manchu dictionaries, both monolingual and multilingual like the Pentaglot. Among his directives were to eliminate directly borrowed loanwords from Chinese and replace them with calque translations which were put into new Manchu dictionaries. This showed in the titles of Manchu translations of Chinese works during his reign which were direct translations contrasted with Manchu books translated during the Kangxi Emperor's reign which were Manchu transliterations of the Chinese characters.

The Pentaglot was based on the Yuzhi Siti Qing Wenjian (御製四體清文鑑; "Imperially-Published Four-Script Textual Mirror of Qing"), with Uyghur added as fifth language.[35] The four-language version of the dictionary with Tibetan was in turn based on an earlier three-language version with Manchu, Mongolian, and Chinese called the "Imperially-Published Manchu Mongol Chinese Three pronunciation explanation mirror of Qing" (御製滿珠蒙古漢字三合切音清文鑑), which was in turn based on the "Imperially-Published Revised and Enlarged mirror of Qing" (御製增訂清文鑑) in Manchu and Chinese, which used both Manchu script to transcribe Chinese words and Chinese characters to transcribe Manchu words with fanqie.[36]

Studies by outsiders

A number of European scholars in the 18th century were frustrated by the difficulties in reading Chinese, with its "complicated" writing system and classical writing style. They considered Manchu translations, or parallel Manchu versions, of many Chinese documents and literary works very helpful for understanding the original Chinese. De Moyriac de Mailla (1669–1748) benefited from the existence of the parallel Manchu text when translating the historical compendium Tongjian Gangmu (Tung-chien Kang-mu; 资治通鉴纲目). Jean Joseph Amiot, a Jesuit scholar, consulted Manchu translations of Chinese works as well, and wrote that the Manchu language "would open an easy entrance to penetrate … into the labyrinth of Chinese literature of all ages."[37]

Study of the Manchu language by Russian sinologists started in the early 18th century, soon after the founding of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Beijing, to which most early Russian sinologists were connected.[38] Illarion Kalinovich Rossokhin (died 1761) translated a number of Manchu works, such as The history of Kangxi's conquest of the Khalkha and Oirat nomads of the Great Tartary, in five parts (История о завоевании китайским ханом Канхием калкаского и элетского народа, кочующего в Великой Татарии, состоящая в пяти частях), as well as some legal treatises and a Manchu–Chinese dictionary. In the late 1830s, Georgy M. Rozov translated from Manchu the History of the Jin (Jurchen) Dynasty.[39] A school to train Manchu language translators was started in Irkutsk in the 18th century, and existed for a fairly long period.[39]

An anonymous author remarked in 1844 that the transcription of Chinese words in Manchu alphabet, available in the contemporary Chinese–Manchu dictionaries, was more useful for learning the pronunciation of Chinese words than the inconsistent romanizations used at the time by the writers transcribing Chinese words in English or French books.[37]

In 1930, the German sinologist Erich Hauer argued forcibly that knowing Manchu allows the scholar to render Manchu personal and place names that have been "horribly mutilated" by their Chinese transliterations and to know the meanings of the names. He goes on that the Manchu translations of Chinese classics and fiction were done by experts familiar with their original meaning and with how best to express it in Manchu, such as in the Manchu translation of the Peiwen yunfu. Because Manchu is not difficult to learn, it "enables the student of Sinology to use the Manchu versions of the classics […] in order to verify the meaning of the Chinese text".[40]

Current situation

Currently, several thousand people can speak Manchu as a second language through primary education or free classes for adults offered in China.[4][5] However very few native Manchu speakers remain. In what used to be Manchuria virtually no one speaks the language, the entire area having been completely sinicized. As of 2007, the last native speakers of the language were thought to be 18 octogenarian residents of the village of Sanjiazi (Manchu: ᡳᠯᠠᠨ

ᠪᠣᡠ᠋, Möllendorff: ilan boo, Abkai: ilan bou), in Fuyu County, in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Province.[41] A few speakers also remain in Dawujia village in Aihui District of Heihe Prefecture.

The Xibe (or Sibe) are often considered to be the modern custodians of the written Manchu language. The Xibe live in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County near the Ili valley in Xinjiang, having been moved there by the Qianlong Emperor in 1764. Modern written Xibe is very close to Manchu, although there are slight differences in the writing system which reflect distinctive Xibe pronunciation. More significant differences exist in morphological and syntactic structure of the spoken Xibe language. For one example among many, there is a "converb" ending, -mak, that is very common in modern spoken Xibe but unknown in Manchu.

Revitalization movements

Recently, there have been increased efforts to revive the Manchu language. Revival movements are linked to the reconstruction of ethnic Manchu identity in the Han-dominated country. The Manchus mainly lead the revival efforts, with support from the PRC state, NGOs and international efforts.[42][43]

Revivalism began in the post-Mao era when non-Han ethnic expression was allowed. By the 1980s, Manchus had become the second largest minority group in China. People began to reveal their ethnic identities that had been hidden due to 20th century unrests and the fall of the Qing Empire.[42][43]

Language revival was one method the growing numbers of Manchus used in order to reconstruct their lost ethnic identity. Language represented them and set them apart from other minority groups in the "plurality of ethnic cultures within one united culture". Another reason for revivalism lay in the archives of the Qing Empire–a way to translate and resolve historical conflicts between the Manchus and the state.[42] Lastly, the people wanted to regain their language for the rituals and communication to their ancestors–many shamans do not understand the words they use.[43]

Manchu associations can be found across the country, including Hong Kong, as well as abroad, in Taiwan. Consisting of mostly Manchus and Mongols, they act as the link between the people, their ethnic leaders and the state.[42]

NGOs provide large support through "Manchu classes". Manchu is now taught in certain primary schools as well as in universities.[43] Heilongjiang University Manchu language research center in no.74, Xuefu Road, Harbin, listed Manchu as an academic major. It is taught there as a tool for reading Qing-dynasty archival documents.[44] In 2009 The Wall Street Journal reported that the language is offered (as an elective) in one university, one public middle school, and a few private schools.[44] There are also other Manchu volunteers in many places of China who freely teach Manchu in the desire to rescue the language.[45][46][47][48] Thousands of non-Manchu speakers have learned the language through these measures.[49][50] Despite the efforts of NGOs, they tend to lack support from high-level government and politics.[43]

The state also runs programs to revive minority cultures and languages. Deng Xiaoping promoted bilingual education. However, many programs are not suited to the ethnic culture or to passing knowledge to the younger generations. If the programs were created via "top-down political processes" the locals tend to look at them with distrust. But if they were formed via specialized governmental organizations, they fare better. According to Katarzyna Golik:[43]

In Mukden, the historical Manchurian capital, there is a Shenyang Manchu Association (沈阳市满族联谊会) which is active in promoting Manchurian culture. The Association publishes books about Manchurian folklore and history and its activities are run independently from the local government. Among the various classes of the Manchurian language and calligraphy some turned out to be a success. Beijing has the biggest and most wealthy Beijing Daxing Regency Manchu Association (北京大兴御苑满族联谊会). (pp100-101)

Other support can be found internationally and on the Internet. Post-Cultural Revolution reform allowed for international studies to be done in China. The dying language and ethnic culture of Manchus gained attention, providing local support.[42] Websites facilitate communication of language classes or articles.[43] Younger generations also spread and promote their unique identity through popular Internet media.[42]

Despite the increased efforts to revive the Manchu language, there are many obstacles standing in the way. Even with increased awareness, many Manchus choose to give up their language, some opting to learn Mongolian instead. Manchu language is still thought of as a foreign language in a Han-dominated Chinese speaking country.[43] Obstacles are also found when gaining recognition from the state. Resistance through censorship prevented the performing of Banjin festivals, a festival in recognition of a new reconstructed Manchu identity, in Beijing.[42]

Phonology

Written Manchu was close to being called an "open syllable" language because the only consonant that came regularly at the end of native words was /n/, similar to Beijing Mandarin, Northeastern Mandarin, Jilu Mandarin and Japanese. This resulted in almost all native words ending in a vowel. In some words, there were vowels that were separated by consonant clusters, as in the words ilha ('flower') and abka ('heaven'); however, in most words, the vowels were separated from one another by only single consonants.

This open syllable structure might not have been found in all varieties of spoken Manchu, but it was certainly found in the southern dialect that became the basis for the written language. It is also apparent that the open-syllable tendency of the Manchu language had been growing ever stronger for the several hundred years since written records of Manchu were first produced: consonant clusters that had appeared in older forms, such as abka and abtara-mbi ('to yell'), were gradually simplified, and the words began to be written as aga or aha (in this form meaning 'rain') and atara-mbi ('to cause a commotion').

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ni⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | |

| Plosive | unaspirated | p ⟨b⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | tʃ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | tʃʰ ⟨c⟩[lower-alpha 1] | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | |

| Fricative | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩[lower-alpha 2] | x ⟨h⟩ | |

| Rhotic | r ⟨r⟩ | ||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | ||

- Or ⟨ch⟩, ⟨q⟩.

- Or ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ś⟩, ⟨x⟩.

Manchu has twenty consonants, shown in the table using each phoneme's representation in the IPA, followed by its romanization in italics. /pʰ/ was rare and found mostly in loanwords and onomatopoeiae, such as pak pik ('pow pow'). Historically, /p/ appears to have been common, but changed over time to /f/. /ŋ/ was also found mostly in loanwords and onomatopoeiae and there was no single letter in the Manchu alphabet to represent it, but rather a digraph of the letters for /n/ and /k/. [ɲ] is usually transcribed with a digraph ni, and has thus often been considered a sequence of phonemes /nj/ rather than a phoneme of its own, though work in Tungusic historical linguistics suggests that the Manchu palatal nasal has a very long history as a single segment, and so it is shown here as phonemic.

Early Western descriptions of Manchu phonology labeled Manchu b as "soft p", Manchu d as "soft t", and Manchu g as "soft k", whereas Manchu p was "hard p", t was "hard t", and k was "hard k". This suggests that the phonological contrast between the so-called voiced series (b, d, j, g) and the voiceless series (p, t, c, k) in Manchu as it was spoken during the early modern era was actually one of aspiration (as shown here) or tenseness, as in Mandarin.

/s/ was affricated to [ts] in some or all contexts. /tʃʰ/, /tʃ/, and /ʃ/ together with /s/ were palatalized before /i/ or /y/ to [tɕʰ], [tɕ], and [ɕ], respectively. /kʰ/ and /k/ were backed before /a/, /ɔ/, or /ʊ/ to [qʰ] and [q], respectively. Some scholars analyse these uvular realizations as belonging to phonemes separate from /kʰ/ and /k/, and they were distinguished in the Manchu alphabet, but are not distinguished in the romanization.

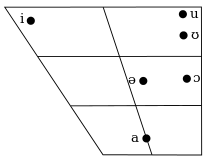

Vowels

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| mid-high | ʊ ⟨ū⟩ | ||

| mid | ə~ɤ ⟨e⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩ | |

| low | ɑ ⟨a⟩ |

In this vowel system, the "neutral" vowels (i and u) were free to occur in a word with any other vowel or vowels. The lone front vowel (e, but generally pronounced like Mandarin [ɤ] ) never occurred in a word with either of the regular back vowels (o and a), but because the rules of vowel harmony are not perceptible with diphthongs, the diphthong eo occurs in some words, i.e. deo, "younger brother", geo, "a mare", jeo, "department", leole, "to discuss", leose, "building", and šeole, "to embroider", "to collect".[52]

e is pronounced as /e/ after y, as in niyengniyeri /ɲeŋɲeri/.

Between n and y, i is absorbed into both consonants as /ɲ/.

The relatively rare vowel transcribed ū (pronounced [ʊ][53]) was usually found as a back vowel; however, in some cases, it was found occurring along with the front vowel e. Much disputation exists over the exact pronunciation of ū. Erich Hauer, a German sinologist and Manchurist, proposes that it was pronounced as a front rounded vowel initially, but a back unrounded vowel medially.[54] William Austin suggests that it was a mid-central rounded vowel.[55] The modern Xibe pronounce it identically to u.

Diphthongs

There are altogether eighteen diphthongs and six triphthongs. The diphthongs are ai, ao, ei, eo, ia, ie, ii, io, iu, oi, oo, ua, ue, ui, uo, ūa, ūe, ūi, and ūo. The triphthongs are ioa, ioo (which is pronounced as /joː/), io(w)an, io(w)en, ioi (/y/), and i(y)ao, and they exist in Chinese loanwords.[53]

The diphthong oo is pronounced as /oː/, and the diphthong eo is pronounced as /ɤo/.

Loanwords

Manchu absorbed a large number of non-native sounds into the language from Chinese. There were special symbols used to represent the vowels of Chinese loanwords. These sounds are believed to have been pronounced as such, as they never occurred in native words. Among these, was the symbol for the high unrounded vowel (customarily romanized with a y, /ɨ/) found in words such as sy (Buddhist temple) and Sycuwan (Sichuan); and the triphthong ioi which is used for the Chinese ü sound. Chinese affricates were also represented with consonant symbols that were only used with loanwords such as in the case of dzengse (orange) (Chinese: chéngzi) and tsun (inch) (Chinese: cùn). In addition to the vocabulary that was borrowed from Chinese, such as the word pingguri (apple) (Chinese: píngguǒ), the Manchu language also had a large amount of loanwords from other languages such as Mongolian, for example the words morin (horse) and temen (camel).

Vowel harmony

The vowel harmony found in the Manchu language was traditionally described in terms of the philosophy of the I Ching. Syllables with front vowels were described as being as "yin" syllables whereas syllables with back vowels were called "yang" syllables. The reasoning behind this was that the language had a kind of sound symbolism where front vowels represented feminine objects or ideas and the back vowels represented masculine objects or ideas. As a result, there were a number of word pairs in the language in which changing the vowels also changed the gender of the word. For example, the difference between the words hehe (woman) and haha (man) or eme (mother) and ama (father) was essentially a contrast between the front vowel, [e], of the feminine and the back vowel, [a], of the masculine counterpart.

Dialects

Dialects of Manchu include a variety of its historical and remaining spoken forms throughout Manchuria, and the city of Beijing (the capital). Notable historical Manchu dialects include Beijing, Ningguta, Alcuka and Mukden dialects.

Beijing Manchu dialect

Many of the Manchu words are now pronounced with some Chinese peculiarities of pronunciation, so k before i and e=ch', g before i and e=ch, h and s before i=hs, etc. H before a, o, u, ū, is the guttural Scotch or German ch.

A Manchu Grammar: With Analysed Texts, Paul Georg von Möllendorff, p. 1.[56]

The Chinese Northern Mandarin dialect spoken in Beijing had a major influence on the phonology of the dialect of Manchu spoken in that city, and because Manchu phonology was transcribed into Chinese and European sources based on the sinicized pronunciation of Manchus from Beijing, the original authentic Manchu pronunciation is unknown to scholars.[57][58]

The Manchus of Beijing were influenced by the Chinese dialect spoken in the area to the point where pronouncing Manchu sounds was hard for them, and they pronounced Manchu according to Chinese phonetics, whereas the Manchus of Aigun (in Heilongjiang) could both pronounce Manchu sounds properly and mimic the sinicized pronunciation of Manchus in Beijing, because they learned the Beijingese pronunciation from either studying in Beijing or from officials sent to Aigun from Beijing, and they could tell them apart, using the Chinese influenced Beijingese pronunciation when demonstrating that they were better educated or their superior stature in society.[59][60]

Changes in vowels

Phonetically, there are some characteristics that differentiate the Beijing accent from the standard spelling form of Manchu.

- There are some occasional vowel changes in a word. For example ᠴᡳᠮᠠᡵᡳ (cimari /t͡ʃʰimari/) is pronounced [t͡ʃʰumari], ᠣᠵᠣᡵᠠᡴᡡ (ojorakū /ot͡ʃoraqʰʊ/) is pronounced [ot͡ɕiraqʰʊ], and ᡤᡳᠰᡠᠨ (gisun /kisun/) is pronounced [kysun].

- In particular, when the vowel /o/ or diphthong /oi/ appears at the beginning of a word, it is frequently pronounced [ə] and [əi] respectively in Beijing accent. For example, ᠣᠩᡤᠣᠯᠣ (onggolo /oŋŋolo/) is pronounced [əŋŋolo], ᠣᡳᠯᠣ (oilo /oilo/) is pronounced [əilo].

- Diphthongization of vowels. /ə/ becomes /əi/ (such as ᡩᡝᡥᡳ dehi /təxi/ pronounced [təixi]), /a/ becomes [ai] (such as ᡩᠠᡤᡳᠯᠠᠮᠪᡳ dagilambi /takilampi/ pronounced [taikilami]), and /i/ becomes [iu] (such as ᠨᡳᡵᡠ niru /niru/ pronounced [niuru], and ᠨᡳᠴᡠᡥᡝ nicuhe /nit͡ʃʰuxə/ pronounced [niut͡ʃʰuxə]).

- /oi/ becomes [uai], especially after /q/ (g). For example, ᡤᠣᡳ᠌ᠮᠪᡳ goimbi /koimpi/ becomes [kuaimi].

- Loss of vowels under certain conditions. The vowel /i/ following consonant /t͡ʃʰ/ (c) or /t͡ʃ/ (j) usually disappears. For example, ᡝᠴᡳᡴᡝ ecike /ət͡ʃʰikʰə/ is pronounced [ət͡ʃʰkʰə], and ᡥᠣᠵᡳᡥᠣᠨ hojihon /χot͡ʃiχon/ is pronounced [χot͡ʃχon]. There are also other cases where a vowel disappears in Beijing accent. For example, ᡝᡴᡧᡝᠮᠪᡳ ekšembi /əkʰʃəmpi/ is pronounced [əkʰʃmi], and ᠪᡠᡵᡠᠯᠠᠮᠪᡳ burulambi /purulampi/ is pronounced [purlami].

Changes in Consonants

This section is primarily based upon Aisin Gioro Yingsheng's Miscellaneous Knowledge of Manchu (满语杂识).[61]

- Systemic merger of /q/ and /χ/ into [ʁ], and /k/ and /x/ into [ɣ] between voiced phonemes. For example, ᠰᠠᡵᡤᠠᠨ (sargan /sɑrqɑn/) is pronounced as [sɑrʁɑn], and ᡠᡵᡤᡠᠨ (urgun /urkun/) is pronounced as [urɣun].

- Conversely, /χ/ may be pronounced as [qʰ] at the beginning of a word. For example, ᡥᠠᠮᡳᠮᠪᡳ (hamimbi /χɑmimpi/) is pronounced as [qʰamimi].

- Assmilation of alveolar and postalveolar stops after /n/. For example, ᠪᠠᠨᠵᡳᠮᠪᡳ (banjimbi /pɑnt͡ʃimpi/) is pronounced as [pɑnnimi], and ᡥᡝᠨᡩᡠᠮᠪᡳ (hendumbi /xəntumpi/) is pronounced as [xənnumi].

- /si/ is pronounced as [ʃɨ] in the middle of a word. For example, ᡠᠰᡳᡥᠠ (usiha /usiχɑ/) is pronounced as [uʃɨʁɑ].

Grammar

Syntax

All Manchu phrases are head-final; the head-word of a phrase (e.g. the noun of a noun phrase, or the verb of a verb phrase) always falls at the end of the phrase. Thus, adjectives and adjectival phrases always precede the noun they modify, and the arguments to the verb always precede the verb. As a result, Manchu sentence structure is subject–object–verb (SOV).

Manchu uses a small number of case-marking particles that are similar to those found in Korean, but there is also a separate class of true postpositions. Case markers and postpositions can be used together, as in the following sentence:

bi

I

tere

that

niyalma-i

person-GEN

emgi

with

gene-he

go-PST

I went with that person

In this example, the postposition emgi, "with", requires its nominal argument to have the genitive case, which causes the genitive case marker i between the noun niyalma and the postposition.

Manchu also makes extensive use of converb structures and has an inventory of converbial suffixes to indicate the relationship between the subordinate verb and the finite verb that follows it. An example is these two sentences, which have finite verbs:

tere

that

sargan

woman

boo

house

ci

ABL

tuci-ke

go out-PST.FIN

That woman came out of the house.

tere

that

sargan

woman

hoton

town

de

DAT

gene-he

go-PST.FIN

That woman went to town.

Both sentences can be combined into a single sentence by using converbs, which relate the first action to the second:

tere

that

sargan

woman

boo

house

ci

ABL

tuci-fi,

go out-PST.CVB,

hoton

town

de

DAT

gene-he

go-PST.FIN

That woman, having come out of the house, went to town.

tere

that

sargan

woman

boo

house

ci

ABL

tuci-me,

go out-IMPERF.CVB,

hoton

town

de

DAT

gene-he

go-PST.FIN

That woman, coming out of the house, went to town.

tere

that

sargan

woman

boo

house

ci

ABL

tuci-cibe,

go out-CONC.CVB,

hoton

town

de

DAT

gene-he

go-PST.FIN

That woman, though she came out of the house, went to town.

Cases

Manchu has five cases, which are marked by particles:[62] nominative, accusative, genitive, dative-locative, and ablative. The particles can be written with the noun to which they apply or separately. They do not obey the rule of vowel harmony but are also not truly postpositions.

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | ||

| exclusive | inclusive | ||||||

| Nominative | bi | be | muse | si | suwe | i | ce |

| Accusative | mimbe | membe | musebe | simbe | suwembe | imbe | cembe |

| Genitive | mini | meni | musei | sini | suweni | ini | ceni |

| Dative | minde | mende | musede | sinde | suwende | inde | cende |

| Ablative | minci | menci | museci | sinci | suwenci | inci | cenci |

Nominative

One of the principal syntactic cases, it is used for the subject of a sentence and has no overt marking.[62]

Accusative

(be): one of the principal syntactic cases, it indicates participants/direct object of a sentence. Direct objects sometimes also take the nominative. It is commonly felt that the marked accusative has a definite sense, like using a definite article in English. It is written separate from the word that it follows.[62] The accusative can be used in the following ways:

- Nominative-accusative strategy – indicates opposition between syntactic roles (subject = nominative; object – accusative)

i

he

boo

house

be

ACC

weile-mbi

build-IMPERF

"He builds a house"

- Transitive verbs

fe

old

kooli

regulations

be

ACC

dahame

according.to

yabu-mbi

act-IMPERF

"(Someone) acts according to old regulations"

- Transitive verb (negative form)

- Indicate when agent is caused to perform an action

- Indicate motion that is happening[62]

Genitive

(i or ni): one of the principal syntactic cases, IT is used to indicate possession or the means by which something is accomplished.[62]

Its primary function is to indicate the possessor of an object:

boo

house

i

GEN

ejen

master

"the master of the house"

It can also indicate a person's relationships:

han

khan

i

GEN

jui

child

"the khan's child"

Other functions of genitive are:

- Attributive: nouns followed by genitive marker indicate attributives, which are also used for participles and verbs.

- Adverb: the noun is repeated with the addition of the genitive marker (i)[62]

Dative-locative

(de): indicates location, time, place, or indirect object.[62]

Its primary function is to indicate the semantic role of the recipient:

ere

this

niyalma

man

de

DAT

bu-mbi

give-IMPERF

"(Someone) gives to this man"

It also has other functions:

- Agent of a passive verb

- Indicate person who is in possession of something

- Indicate sources of something

- Indicate instrument of action (verbs in past tense, talking about others)[62]

Ablative

(ci): indicates the origin of an action or the basis for a comparison.[62]

That can be the starting point in space or time:

boo-ci

house-ABL

tuci-ke

go.away-PAST

"(Someone) went away from the house"

It can also be used to compare objects:

ere

this

erin

time

ci

ABL

oyonggo

important

ningge

NMLZ

akū

COP.NEG

"There is no time more important than the present"

The deri form was used in Classical Manchu, and different scholars have specified different meanings:

- Replace ci

- Comparisons

encu

other

hehe-ši

woman-PL

(ma. hehe-si)

deri

from

fulu

better

tua-mbi

consider-IMPERF

(ma. tuwa-mbi)

"(He) began to consider her better than other women"[62]

Less-used cases

- Terminative: indicates the ending point of an action by the suffix -tala/-tele/-tolo.

- Indefinite allative: indicates "to a place, to a situation" when it is unknown whether the action reaches exactly to the place or situation or around or near it by the suffix -si.

- Indefinite locative: indicates "at a place, in a situation" when it is unknown whether the action happens exactly at the place or situation or around or near it by the suffix -la/-le/-lo.

- Indefinite ablative: indicates "from a place, from a situation" when it is unknown whether the action is really from the exact place or situation or around or near it by the suffix -tin.

- Distributive: indicates every one of something by the suffix -dari.

- Essive-formal: indicates a simile ("as/like") by the suffix -gese.

- Identical: indicates that something is the same as something else by the suffix -ali/-eli/-oli (apparently derived from the word adali, meaning "same").

- Orientative: indicates "facing/toward" (something/an action) and shows only position and tendency, not movement into by the suffix -ru.

- Revertive: indicates "backward" or "against (something)" from the root 'ca' (see cargi, coro, cashu-n, etc.) by the suffix -ca/-ce/-co.

- Translative: indicates change in the quality or form of something by the suffix -ri.

- Indefinite accusative: indicates that the touch of the verb on the object is not surely complete by the suffix -a/-e/-o/-ya/-ye/-yo'.'

In addition, there were some suffixes, such as the primarily-adjective-forming suffix -ngga/-ngge/-nggo, that appear to have originally been case markers (in the case of -ngga, marking the genitive case) but had already lost their productivity to become fossilized in certain lexemes by the time of the earliest written records of the Manchu language: agangga "pertaining to rain" as in agangga sara (an umbrella), derived from Manchu aga (rain).

Verbs

There are 13 basic verb forms, some of which can be further modified with the verb bi (is), or the particles akū, i, o, and ni (negative, instrumental, and interrogatives).

| Form | Usual Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|

| imperative | ∅ | afa |

| imperfect participle | -ra/re/ro | afara |

| perfect participle | -ha/he/ho | afaha |

| imperfect converb | -me | afame |

| perfect converb | -fi | afafi |

| conditional | -ci | afaci |

| concessive | -cibe | afacibe |

| terminal converb | -tala/tele/tolo | afatala |

| prefatory converb | -nggala/nggele/nggolo | afanggala |

| desiderative 1 | -ki | afaki |

| desiderative 2 | -kini | afakini |

| optative | -cina | afacina |

| temeritive | -rahū | afarahū |

Imperfect Participle

The imperfect participle is formed by adding the variable suffix -ra, -re, -ro to the stem of the verb. Ra occurs when the final syllable of the stem contains an a. Re occurs when the final syllable of the stem contains e, i, u or ū. Ro occurs with stems containing all o's. An irregular suffix -dara, -dere, -doro is added to a limited group of irregular verbs (jon-, wen-, ban-) with a final -n. (The perfect participle of these verbs is also irregular). Three of the most common verbs in Manchu also have irregular forms for the imperfect participle:

- bi-, bisire — 'be'

- o-, ojoro — 'become'

- je-, jetere — 'eat'

Imperfect participles can be used as objects, attributes, and predicates. Using ume alongside the imperfect participle makes a negative imperative.

As an attribute:

habša-ra

complain-IPTC

niyalma

man

"A man who complains"

When this form is used predicatively it is usually translated as a future tense in English; it often carries an indefinite or conditional overtone when used in this fashion:

bi

1sg

sinde

2sg-ACC

ala-ra

tell-IPTC

"I'll tell you"

As an object:

gisure-re

speak-IPTC

be

ACC

han

king

donji-fi

hear-PCVB

"The king having heard what was being said"

Writing system

The Manchu language uses the Manchu script, which was derived from the traditional Mongol script, which in turn was based on the vertically written pre-Islamic Uyghur script. Manchu is now usually romanized according to the transliteration system employed by Jerry Norman in his Comprehensive Manchu-English Dictionary (2013). The Jurchen language, which is ancestral to Manchu, used the Jurchen script, which is derived from the Khitan script, which in turn was derived from Chinese characters. There is no relation between the Jurchen script and the Manchu script.

Chinese characters, employed as phonograms, can also be used to transliterate Manchu.[65] All the Manchu vowels and the syllables commencing with a consonant are represented by single Chinese characters as are also the syllables terminating in i, n, ng and o; but those ending in r, k, s, t, p, I, m are expressed by the union of the sounds of two characters, there being no Mandarin syllables terminating with these consonants. Thus the Manchu syllable am is expressed by the Chinese characters 阿木 a mù, and the word Manchu is, in the Kangxi Dictionary, written as 瑪阿安諸烏 mă ā ān zhū wū.[66]

Teaching

Mongols learned their script as a syllabary, dividing the syllables into twelve different classes,[67][68] based on the final phonemes of the syllables, all of which ended in vowels.[69][70] The Manchus followed the same syllabic method when learning Manchu script, also with syllables divided into twelve different classes based on the finals phonemes of the syllables. Today, the opinion on whether it is alphabet or syllabic in nature is still split between different experts. In China, it is considered syllabic and Manchu is still taught in this manner. The alphabetic approach is used mainly by foreigners who want to learn the language. Studying Manchu script as a syllabary takes a longer time.[71][72]

Despite the alphabetic nature of its script, Manchu was not taught phoneme per letter like western languages are; Manchu children were taught to memorize all the syllables in the Manchu language separately as they learned to write, like Chinese characters. To paraphrase Meadows 1849,[73]

Manchus when learning, instead of saying l, a—la; l, o—lo; &c., were taught at once to say la, lo, &c. Many more syllables than are contained in their syllabary might have been formed with their letters, but they were not accustomed to arrange them otherwise. They made, for instance, no such use of the consonants l, m, n, and r, as westerners do; hence if the Manchu letters s, m, a, r, t, are joined in that order a Manchu would not able to pronounce them as English speaking people pronounce the word 'smart'.

However this was in 1849, and more research should be done on the current teaching methods used in the PRC.

Further reading

Learning texts of historical interest

- Paul Georg von Möllendorff (1892). A Manchu grammar: with analysed texts. Printed at the American Presbyterian mission press. pp. 52. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- A. Wylie (1855). Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Thomas Taylor Meadows (1849). Translations from the Manchu: with the original texts, prefaced by an essay on the language. Canton: Press of S.W. Williams. pp. 54http://www.endangeredlanguages.com/lang/1205/guide/6302. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

For readers of Chinese

- Liu, Jingxian; Zhao, Aping; Zhao, Jinchun (1997). 满语研究通论 (General Theory of Manchu Language Research). Heilongjiang Korean Nationality Publishing House. ISBN 9787538907650.

- Ji, Yonghai (2011). 满语语法 (Manchu Grammar). Minzu University of China Press. ISBN 9787811089677.

- Aisin Gioro, Yingsheng (2004). 满语杂识 (Divers Knowledges of Manchu language). Wenyuan Publishing House. ISBN 7-80060-008-4.

Literature

- von Möllendorff, P. G. (1890). "Essay on Manchu Literature". Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The Branch. 24–25: 1–45.

- Wade, Thomas Francis (1898). Herbert Allen Giles (ed.). A catalog of the Wade collection of Chinese and Manchu books in the library of the University of Cambridge. University Press.

- Cambridge University Library (1898). A Catalogue of the Collection of Chinese and Manchu Books Given to the University of Cambridge. The University Press.

- James Summers, ed. (1872). Descriptive catalogue of the Chinese, Japanese, and Manchu books.

- Klaproth, Heinrich Julius (1822). Verzeichniss der chinesischen und mandshuischen Bücher und Handschriften der K. Bibliothek zu Berlin (in German). Paris: In der Königlichen Drunerel.

References

Citations

- "Manchu Ethnologue". 17 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016.

- Manchu at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 抢救满语振兴满族文化 (in Chinese). 26 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- China News (originally Beijing Morning Post): Manchu Classes in Remin University (Simplified Chinese)

- Phoenix Television: Jinbiao's 10-year Manchu Dreams

- Moseley, Christopher, ed. (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Memory of Peoples (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Fletcher (1973), p. 141.

- Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919. BRILL. 21 August 2014. p. 169. ISBN 978-90-04-27927-8.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley; Helen F. Siu; Professor of Anthropology Helen F Siu; Donald S. Sutton, Professor of History and Anthropology Donald S Sutton (19 January 2006). Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-520-23015-6.

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China: Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Modern China. Sage Publications. 32 (1): 12. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. S2CID 144587815. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- S. Robert Ramsey (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press. pp. 213–. ISBN 0-691-01468-X.

- von Möllendorff (1890).

- Edward J. M. Rhoads, Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press, 2000. Pages 52–54. ISBN 0-295-98040-0. Partially available on Google Books

- Yu Hsiao-jung, Manchu Rule over China and the Attrition of the Manchu Language Archived 19 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Rhoads (2000), p. 95.

- Lague, David (17 March 2007). "Manchu Language Lives Mostly in Archives". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Idema, Wilt L., ed. (2007). Books in Numbers: Seventy-fifth Anniversary of the Harvard-Yenching Library : Conference Papers. Vol. 8 of Harvard-Yenching Institute studies. Chinese University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-9629963316.

- Naquin, Susan (2000). Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900. University of California Press. p. 382. ISBN 0520923456.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2017). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928. University of Washington Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0295997483.

- Adolphson, Mikael S. (2003). Hanan, Patrick (ed.). Treasures of the Yenching: Seventy-fifth Anniversity of the Harvard-Yenching Library : Exhibition Catalogue. Vol. 1 of Harvard-Yenching Library studies: Harvard Yenching Library. Chinese University Press. p. 84. ISBN 9629961024.

- Adolphson, Mikael S. (2003). Hanan, Patrick (ed.). Treasures of the Yenching: Seventy-fifth Anniversity of the Harvard-Yenching Library : Exhibition Catalogue. Vol. 1 of Harvard-Yenching Library studies: Harvard Yenching Library. Chinese University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9629961024.

- Mosca, Mathew W. (December 2011). "The Literati rewriting of China in The QianLong-Jiaqing Transition". Late Imperial China. the Society for Qing Studies and The Johns Hopkins University Press. 32 (2): 106–107. doi:10.1353/late.2011.0012. S2CID 144227944.

- Mosca, Mathew W. (2010). "Empire and the Circulation of Frontier Intelligence Qing Conceptions of the Ottomans". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. The Harvard-Yenching Institute. 70 (1): 181. doi:10.1353/jas.0.0035. S2CID 161403630.

- Mosca, Mathew W. (2010). "Empire and the Circulation of Frontier Intelligence Qing Conceptions of the Ottomans". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. The Harvard-Yenching Institute. 70 (1): 182. doi:10.1353/jas.0.0035. S2CID 161403630.

- Mosca, Mathew W. (2010). "Empire and the Circulation of Frontier Intelligence Qing Conceptions of the Otomans". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. The Harvard-Yenching Institute. 70 (1): 176. doi:10.1353/jas.0.0035. S2CID 161403630.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2017). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0295997483.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2017). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0295997483.

- Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China. Vol. 27 of Studies on China. University of California Press. 2005. p. 321. ISBN 0520927796.

- Idema, Wilt L., ed. (2007). Books in Numbers: Seventy-fifth Anniversary of the Harvard-Yenching Library : Conference Papers. Vol. 8 of Harvard-Yenching Institute studies. Chinese University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-9629963316.

- Kuo, Ping Wen (1915). The Chinese System of Public Education, Issue 64. Vol. 64 of Teachers College New York, NY: Contrib. to education (2 ed.). Teachers College, Columbia University. p. 58.

- Contributions to Education, Issue 64. Bureau of Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. 1915. p. 58.

- Jami, Catherine (2012). The Emperor's New Mathematics: Western Learning and Imperial Authority During the Kangxi Reign (1662–1722) (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0199601400.

- Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China. Vol. 27 of Studies on China. University of California Press. 2005. p. 323. ISBN 0520927796.

- Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008). Chinese Lexicography : A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911: A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911. Oxford University Press. p. 398. ISBN 978-0191561672. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008). Chinese Lexicography : A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911: A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911. Oxford University Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-0191561672. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Anonymous, "Considerations on the language of communication between the Chinese and European governments", in The Chinese Repository, vol XIII, June 1844, no. 6, pp. 281–300. Available on Google Books. Modern reprint exists, ISBN 1-4021-5630-8

- Liliya M. Gorelova, "Manchu Grammar." Brill, Leiden, 2002. ISBN 90-04-12307-5

- История золотой империи. (The History of the Jin (Jurchen) Dynasty) Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch. Novosibirsk, 1998. 2 ISBN 5-7803-0037-2. Editor's preface (in Russian)

- Hauer (1930), p. 162-163.

- Lague, David (18 March 2007). "Chinese Village Struggles to Save Dying Language". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Identity reproducers beyond the grassroots: The middle class in the Manchu revival since 1980s". Asian Ethnicity. 6.

- "Facing the Decline of Minority Languages: The New Patterns of Education of Mongols and Manchus". The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities.

- Ian Johnson (5 October 2009), "In China, the Forgotten Manchu Seek to Rekindle Their Glory", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 5 October 2009

- "China Nationality Newspaper: the Rescue of Manchu Language (simplified Chinese)". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "iFeng: Jin Biao's 10-Year Dream of Manchu Language (traditional Chinese)". Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Shenyang Daily: Young Man Teaches Manchu For Free To Rescue the Language (simplified Chinese)". Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Beijing Evening News: the Worry of Manchu language (simplified Chinese)". 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Northeastern News: Don't let Manchu language and scripts become a sealed book (simplified Chinese)". Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- "Beijing Evening News: 1980s Generation's Rescue Plan of Manchu Language (simplified Chinese)". bjwb.bjd.com.cn. 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Tawney, Brian. "Reading Jakdan's Poetry: An Exploration of Literary Manchu Phonology". MA Thesis (Harvard, RSEA).

- Liliya M. Gorelova (1 January 2002). Manchu Grammar. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12307-6.

- Paul Georg von Möllendorff (1892). A Manchu Grammar: With Analysed Texts. Printed at the American Presbyterian mission Press. pp. 1–.

- Li (2000), p. 17.

- Austin, William M., "The Phonemics and Morphophonemes of Manchu", in American Studies in Altaic Linguistics, p. 17, Nicholas Poppe (ed.), Indiana University Publications, Vol. 13 of the Uralic and Altaic Series, Bloomington IN 1962

- Möllendorff, Paul Georg von (1892). A Manchu Grammar: With Analysed Texts (reprint ed.). Shanghai: American Presbyterian mission Press. p. 1.

- Gorelova, Liliya M., ed. (2002). Manchu Grammar, Part 8. Vol. 7. Brill. p. 77. ISBN 9004123075.

- Cahiers de linguistique: Asie orientale. Vol. 31–32. Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l'Asie orientale. 2002. p. 208.

- Shirokogoroff, S. M. (1934). "Reading and Transliteration of Manchu Lit.". Archives polonaises d'etudes orientales. Vol. 8–10. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. p. 122.

- Shirokogoroff, S. M. (1934). "Reading and Transliteration of Manchu Lit.". Rocznik orientalistyczny. Vol. 9–10. p. 122.

- Aisin Gioro, Yingsheng (2004). Miscellaneous Knowledge of Manchu [满语杂识] (in Chinese). Beijing: Xueyuan Press. pp. 221–230. ISBN 7-80060-008-4.

- Goreleva, Liliya (2002). Manchu grammar. Leiden: Brill. pp. 163–193.

- "Manchu Studies Group lesson 6 – noun cases" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2023.

- Norman, Jerry (1965). A grammatical sketch of Manchu. Berkeley: University of California Library.

- Asiatic journal and monthly miscellany. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. May–August 1837. p. 197.

- Asiatic journal and monthly miscellany. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. May–August 1837. p. 198.

- Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. 1855. pp. xxvii–.

- Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. pp. xxvii–.

- Chinggeltei. (1963) A Grammar of the Mongol Language. New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. p. 15.

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. University of Hawaii Press. p. 16. ISBN 0824822064. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one.

- Gertraude Roth Li (2010). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents (Second Edition) (2 ed.). Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr. p. 16. ISBN 978-0980045956. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one. Others see it as having an alphabet with individual letters, some of which differ according to their position within a word. Thus, whereas Denis Sinor argued in favor of a syllabic theory,30 Louis Ligeti preferred to consider the Manchu script and alphabetical one.31

() - Thomas Taylor Meadows (1849). Translations from the Manchu: with the original texts, prefaced by an essay on the language. Press of S.W. Williams. pp. 3–.

Sources

- Gorelova M., Liliya (2002). Manchu Grammar (PDF). Leiden; Boston; Köln.: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-12307-5.

- Elliott, Mark (2013). "Why Study Manchu?". Manchu Studies Group.

- Fletcher, Joseph (1973), "Manchu Sources", in Leslie Donald, Colin Mackerras and Wang Gungwu (ed.), Essays on the Sources for Chinese History, Canberra: ANU Press

- Haenisch, Erich. 1961. Mandschu-Grammatik. Leipzig: VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie (in German)

- Hauer, Erich (1930). "Why the Sinologue Should Study Manchu" (PDF). Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 61: 156–164.

- Li, Gertraude Roth (2000). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai`i Press. ISBN 0824822064.

- Erling von Mende. 2015. "In Defence of Nian Gengyao, Or: What to Do About Sources on Manchu Language Incompetence?". Central Asiatic Journal 58 (1-2). Harrassowitz Verlag: 59–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13173/centasiaj.58.1-2.0059.

- Möllendorff, Paul Georg von. 1892. Paul Georg von Möllendorff (1892). A Manchu Grammar: With Analysed Texts. Printed at the American Presbyterian mission Press. Shanghai.

The full text of A Manchu Grammar at Wikisource

The full text of A Manchu Grammar at Wikisource - Norman, Jerry. 1974. "Structure of Sibe Morphology", Central Asian Journal.

- Norman, Jerry. 1978. A Concise Manchu–English Lexicon, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

- Norman, Jerry. 2013. A Comprehensive Manchu–English Dictionary, Harvard University Press (Asia Center), Cambridge ISBN 9780674072138.

- Ramsey, S. Robert. 1987. The Languages of China. Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey ISBN 0-691-06694-9

- Tulisow, Jerzy. 2000. Język mandżurski (« The Manchu language »), coll. « Języki Azjii i Afryki » (« The languages of Asia and Africa »), Dialog, Warsaw, 192 p. ISBN 83-88238-53-1 (in Polish)

- Kane, Daniel. 1997. "Language Death and Language Revivalism the Case of Manchu". Central Asiatic Journal 41 (2). Harrassowitz Verlag: 231–49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41928113.

- Aiyar, Pallavi (26 April 2007). "Lament for a dying language". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

External links

ᡤᡳᠰᡠᠨ

(source texts in Manchu language)

- Manchu Swadesh vocabulary list of basic words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Abkai — Unicode Manchu/Sibe/Daur Fonts and Keyboards

- Manchu language Gospel of Mark

- Manchu alphabet and language at Omniglot

- Mini Buleku A Recorded Sibe Dictionary

- Manchu Test Page

- Manchu–Chinese–English Lexicon

- online Manchu–Chinese, Manchu–Japanese lexicon (in Chinese)

- Anaku Manchu Script Creator (in Chinese)

- "Video: A Dying Language". The New York Times. 15 March 2007. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- Contrast In Manchu Vowel Systems

- Manchu Word Of The Day, Open Source Manchu–English dictionary

- Manju Nikan Inggiri Gisun i Buleku Bithe (Manchu–Chinese–English dictionary)

- Manchu language guide

- The Manchu Studies Group

- Tawney, Brian. "Reading Jakdan's Poetry: An Exploration of Literary Manchu Phonology". AM Thesis (Harvard, RSEA).

- 清代满族语言文字在东北的兴废与影响

- Meadows, Thomas Taylor. 1849. A Manchu chrestomathy with translations

- Klaproth, Julius von. 1828. Chrestomathie mandchou : ou, Recueil de textes mandchou : destiné aux personnes qui veulent s'occuper de l'étude de cette langue (with some texts translated into French)

- Soldierly Methods: Vade Mecum for an Iconoclastic Translation of Sun Zi bingfa. 2008. By Victor H. Mair with a complete transcription and word-for-word glosses of the Manchu translation by H. T. Toh