Micodon

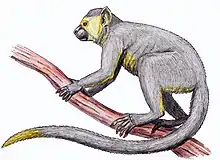

Micodon is an extinct genus of New World monkeys from the Middle Miocene (Laventan in the South American land mammal ages; 13.8 to 11.8 Ma). Its remains have been found at the Konzentrat-Lagerstätte of La Venta in the Honda Group of Colombia. The type species is M. kiotensis,[2] a very small monkey among the New World species.[3]

| Micodon | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Callitrichidae |

| Genus: | †Micodon Setoguchi & Rosenberger 1985[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Micodon kiotensis Setoguchi and Rosenberger 1985 | |

Description

Fossils of Micodon were discovered in the La Victoria Formation, that has been dated to the Laventan, about 13.5 Ma. Micodon is the smallest primate found in the La Venta fauna, and within size range of Saguinus and Callithrix. It differs from most callitrichines in the generally low-relief morphological pattern, large size of the talon basin, and particularly, the considerably large size of hypocone. The morphology and position of the hypocone is distinctly different from the conditions found in such genera as Callimico and Saimiri. By comparison with Micodon, the hypocone is far smaller in Callimico, where it appears as an excrescence of the lingual cingulum. This cusp is more developed in Saimiri. Overall, the Micodon M1 shows some gross resemblances to certain Saguinus, although none of the specimens examined hardly approach this fossil in hypocone development.[4]

Micodon is clearly within the size range of living marmosets but is well below the size range of larger marmosets, such as Callimico goeldii and Leontopithecus chrysopygus. Since the callitrichines are probably a modified radiation that underwent their major diversification at a small body size, it is considered very likely that Micodon is a marmoset. The Micodon M1 suggests that body size/tooth size reduction preceded the loss of the hypocone cusp. It has been argued that the combination of tricuspid molars and small size literally define a marmoset phyletically. On the other hand, Callimico is a four-cusped ceboid whose anatomy suggests that it is cladistically closest to the tricuspid marmosets, and alternative schemes of platyrrhine phylogeny place the four-cusped cebines, Cebus and Saimiri, as the sister-taxon of the entire group. The upshot of these latter views is that a four-cusped molar would be fully expectable in small, ancestral callitrichine, and even in callitrichin sister-group.[5] The upper first molar (M1) with a subtriangular outline with a narrow lingual side resembles that of the oldest New World primate discovered to date, the Late Eocene Perupithecus from the Peruvian Amazon.[6]

It has been suggested the specimens ascribed to Micodon, smaller than Aotus dindensis,[7] may actually be deciduous teeth of another primate species found at La Venta such as Saimiri annectens or S. fieldsi.[8] More material is needed for a better description of the genus.[9]

A body mass of 400 grams (0.88 lb) has been estimated for Micodon.[10]

Habitat

The Honda Group, and more precisely the "Monkey Beds", are the richest site for fossil primates in South America.[11] From the same level as where Micodon has been found, also fossils of Cebupithecia, Mohanamico, Saimiri annectens, Saimiri fieldsi and Stirtonia have been uncovered.[12][13] It has been argued that the monkeys of the Honda Group were living in habitat that was in contact with the Amazon and Orinoco Basins, and that La Venta itself was probably seasonally dry forest.[14] The evolutionary separation from Aotus of Micodon has been placed in the Early Miocene at 17.5 Ma.[15]

References

- T. Setoguchi and A. Rosenberger. 1985. Miocene marmosets; first fossil evidence. International Journal of Primatology 6(6):615-625

- Micodon kiotensis at Fossilworks.org

- Tejedor, 2013, p.29

- Setoguchi et al., 1986, p.764

- Setoguchi et al., 1986, p.766

- Bond et al., 2015, p.538

- Gebo et al., 1990, p.738

- Wheeler, 2010, p.133

- Defler, 2004, p.32

- Silvestro et al., 2017, p.14

- Rosenberger & Hartwig, 2001, p.3

- Luchterhand et al., 1986, p.1753

- Setoguchi et al., 1986, p.762

- Lynch Alfaro et al., 2015, p.520

- Takai et al., 2001, p.304

Bibliography

- Bond, Mariano; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Kenneth E. Campbell Jr.; Laura Chornogubsky; Nelson Novo, and Francisco Goin. 2015. Eocene primates of South America and the African origins of New World monkeys. Nature 520. 538–546. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Defler, Thomas. 2004. Historia natural de los primates colombianos, 1–613. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Gebo, Daniel L.; Marian Dagosto; Alfred L. Rosenberger, and Takeshi Setoguchi. 1990. New platyrrhine tali from La Venta, Colombia. Journal of Human Evolution 19. 737–746. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Luchterhand, Kubet; Richard F. Kay, and Richard H. Madden. 1986. Mohanamico hershkovitzi, gen. et sp. nov., un primate du Miocene moyen d' Amerique du Sud. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences 303. 1753–1758. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Lynch Alfaro, Jessica W.; Liliana Cortés Ortiz; Anthony Di Fiore, and Jean P. Boubli. 2015. Special issue: Comparative biogeography of Neotropical primates. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82. 518–529. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Rosenberger, Alfred L., and Walter Carl Hartwig. 2001. New World Monkeys. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences _. 1–4. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Setoguchi, Takeshi; Nobuo Shigehara; Alfred L. Rosenberger, and Alberto Cadena G. 1986. Primate fauna from the Miocene La Venta, in the Tatacoa Desert, Department of Huila, Colombia. Caldasia XV. 761–773. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Takai, Masanaru; Federico Anaya; Hisashi Suzuki; Nobuo Shigehara, and Takeshi Setoguchi. 2001. A New Platyrrhine from the Middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and the Phyletic Position of Callicebinae. Anthropological Science, Tokyo 109.4. 289–307. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Tejedor, Marcelo F. 2013. Sistemática, evolución y paleobiogeografía de los primates Platyrrhini. Revista del Museo de La Plata 20. 20–39. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Wheeler, Brandon. 2010. Community ecology of the Middle Miocene primates of La Venta, Colombia: the relationship between ecological diversity, divergence time, and phylogenetic richness. Primates 51.2. 131–138. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Further reading

- Fleagle, John G., and Alfred L. Rosenberger. 2013. The Platyrrhine Fossil Record, 1–256. Elsevier ISBN 9781483267074. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Hartwig, W.C., and D.J. Meldrum. 2002. The Primate Fossil Record - Miocene platyrrhines of the northern Neotropics, 175–188. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08141-2. Accessed 2017-09-24.