Mihrab

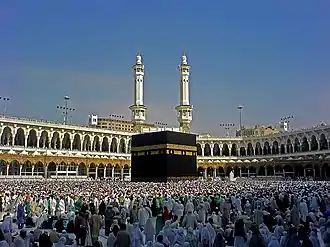

Mihrab (Arabic: محراب, miḥrāb, pl. محاريب maḥārīb) is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall".

.jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

The minbar, which is the raised platform from which an imam (leader of prayer) addresses the congregation, is located to the right of the mihrab.

Etymology

The origin of the word miḥrāb is complicated and multiple explanations have been proposed by different sources and scholars.[1][2] It may come from Old South Arabian (possibly Sabaic) 𐩣𐩢𐩧𐩨 mḥrb meaning a certain part of a palace,[3] as well as "part of a temple where 𐩩𐩢𐩧𐩨 tḥrb (a certain type of visions) is obtained,"[4][5] from the root word 𐩢𐩧𐩨 ḥrb "to perform a certain religious ritual (which is compared to combat or fighting and described as an overnight retreat) in the 𐩣𐩢𐩧𐩨 mḥrb of the temple."[4][5] It may also possibly be related to Ethiopic ምኵራብ məkʷrab "temple, sanctuary,"[6][7] whose equivalent in Sabaic is 𐩣𐩫𐩧𐩨 mkrb of the same meaning,[4] from the root word 𐩫𐩧𐩨 krb "to dedicate" (cognate with Akkadian 𒅗𒊒𒁍 karābu "to bless" and related to Hebrew כְּרוּב kerūḇ "cherub (either of the heavenly creatures that bound the Ark in the inner sanctuary)").

Arab lexicographers traditionally derive the word from the Arabic root ح ر ب (Ḥ-R-B) relating to "war, fighting or anger," (which, though cognate with the South Arabian root,[8] does not however carry any relation to religious rituals) thus leading some to interpret it to mean a "fortress", or "place of battle (with Satan),"[9] the latter due to mihrabs being private prayer chambers. The latter interpretation though bears similarity to the nature of the 𐩢𐩧𐩨 ḥrb ritual.

The word mihrab originally had a non-religious meaning and simply denoted a special room in a house; a throne room in a palace, for example. The Fath al-Bari (p. 458), on the authority of others, suggests the mihrab is "the most honorable location of kings" and "the master of locations, the front and the most honorable." The Mosques in Islam (p. 13), in addition to Arabic sources, cites Theodor Nöldeke and others as having considered a mihrab to have originally signified a throne room.

The term was subsequently used by the Islamic prophet Muhammad to denote his own private prayer room. The room additionally provided access to the adjacent mosque, and Muhammad entered the mosque through this room. This original meaning of mihrab – i.e. as a special room in the house – continues to be preserved in some forms of Judaism where mihrabs are rooms used for private worship. In the Qur'an, the word (when in conjunction with the definite article) is mostly used to indicate the Holy of Holies. The term is used, for example, in the verse "then he [i.e. Zechariah] came forth to his people from the mihrab"[19:11].[10]: 4

History

The earliest mihrabs generally consisted of a simple stripe of paint or a flat stone panel in the qibla wall.[lower-alpha 1] They may have originally had functions similar to a maqsura, denoting not only the place where the imam led prayers but also where some official functions, such as the dispensation of justice, were carried out.[2] In the Mosque of the Prophet (Al-Masjid al-Nabawi) in Medina, a large block of stone initially marked the north wall which was oriented towards Jerusalem (the first qibla), but this was moved to the south wall in the second year of the hijra period (2 AH or 624 CE), when the orientation of the qibla was changed towards Mecca.[11] This mihrab also marked the spot where Muhammad would plant his lance ('anaza or ḥarba) prior to leading prayers.[2]

During the reign of the Umayyad caliph Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik (Al-Walid I, r. 705–715), the Mosque of the Prophet was renovated and the governor (wāli) of Medina, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, ordered that a niche be made to designate the qibla wall (which identifies the direction of Mecca), which became the first concave mihrab niche.[12]: 24 [11] This type of mihrab was called miḥrāb mujawwaf in historical Arabic texts.[2][1] The origin of this architectural feature has been debated by scholars.[2] Some trace it to the apse of Christian churches, others to the alcove shrines or niches of Buddhist architecture.[11][2] Niches were already a common feature of Late Antique architecture prior to the rise of Islam, either as hollow spaces or to house statues. The mihrab niche could have also been related to the recessed area or alcove that sheltered the throne in some royal audience halls.[2]

The next earliest concave mihrab to be documented is the one that was added to the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus when it was built by Al-Walid between 706 and 715.[12]: 24 This was then followed by a mihrab added to the Mosque of 'Amr ibn al-'As in Fustat in 710–711.[11] Subsequently, concave mihrabs became widespread across the Muslim world and were adopted as a standard feature of mosques.[11][12]: 24 The oldest surviving concave mihrab today is a marble mihrab housed at the Iraq Museum. It is believed to date from the 8th century, possibly made in northern Syria before being moved by the Abbasids to the Great Mosque of al-Mansur in Baghdad. It was then moved again to the al-Khassaki Mosque built in the 17th century, where it was later found and transferred to the museum.[11][2][13]: 29 This mihrab features a combination of Classical or Late Antique motifs, with the niche flanked by two spiral columns and crowned by a scalloped shell-like hood.[11][13]: 29 [10]: 5

Eventually, the niche came to be universally understood to identify the qibla wall, and so came to be adopted as a feature in other mosques. A sign was no longer necessary. Today, mihrabs vary in size, but are usually ornately decorated. It was common for mihrabs to be flanked with pairs of candlesticks, though they would not have lit candles.[14] In Ottoman mosques, these were made of brass, bronze or beaten copper and their bases had a distinctive bell shape.[15]

In exceptional cases, the mihrab does not follow the qibla direction, such as is the Masjid al-Qiblatayn, or the Mosque of the Two Qiblas, where Muhammad received the command to change the direction of prayer from Jerusalem to Mecca, thus it has two prayer niches. In 1987 century the mosque was renovated, and the old prayer niche facing Jerusalem was removed, and the one facing Mecca was left.[16]

Architecture

Mihrabs are a relevant part of Islamic culture and mosques. Since they are used to indicate the direction for prayer, they serve as an important focal point in the mosque. They are usually decorated with ornamental detail that can be geometric designs, linear patterns, or calligraphy. This ornamentation also serves a religious purpose. The calligraphy decoration on the mihrabs are usually from the Qur'an and are devotions to God so that God's word reaches the people.[17] Common designs amongst mihrabs are geometric foliage that are close together so that there is no empty space in-between the art.[17]

Great Mosque of Córdoba

The mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordoba is a highly decorated piece of art that draws one's attention. It is a contribution made by Al-Hakam II that is not just used for prayer.[18] It is used as a place of convergence in the mosque, where visitors could be amazed by its beauty and gilded designs. The entrance is covered in mosaics "which links to the Byzantium tradition, produced by the craftsmen sent by Emperor Nicephorus II. These mosaics extend along the voussoirs with a geometric and plant-based design, but also in the inscriptions which record verses from the Koran".[18] This mihrab is also a bit different from a normal mihrab due to its scale. It takes up a whole room instead of just a niche.[19] This style of mihrab set a standard for other mihrab construction in the region.[20] The use of the horseshoe arch, carved stucco, and glass mosaics made an impression for the aesthetic of mihrabs, "although no other extant mihrab in Spain or western North Africa is as elaborate."[20]

Great Mosque of Damascus

The Great Mosque of Damascus was started by al-Walid in 706.[21] It was built as a hypostyle mosque, built with a prayer hall leading to the mihrab, "on the back wall of the sanctuary are four mihrabs, two of which are the mihrab of the Companions of the Prophet in the eastern half and the great mihrab at the end of the transept".[21] The mihrab is decorated similarly to the rest of the mosque in golden vines and vegetal imagery. The lamp that once hung in the mihrab has been theorized as the motif of a pearl, due to the indications that dome of the mihrab has scalloped edges.[22] There have been other mosques that have mihrabs similar to this that follow the same theme, with scalloped domes that are "concave like a conch or mother of pearl shell.[22] The original main mihrab of the mosque has not been preserved, having been renovated many times, and the current one is a replacement dating from renovations after a destructive 1893 fire.[22][23][11]

Gallery

A mihrab in Sultan Ibrahim Mosque in Rethymno

A mihrab in Sultan Ibrahim Mosque in Rethymno_MET_DP235035.jpg.webp) Mihrab (prayer niche); 1354–1355; mosaic of polychrome-glazed cut tiles on stonepaste body, set into mortar; 343.1 x 288.7 cm, weight: 2041.2 kg; from Isfahan (Iran); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mihrab (prayer niche); 1354–1355; mosaic of polychrome-glazed cut tiles on stonepaste body, set into mortar; 343.1 x 288.7 cm, weight: 2041.2 kg; from Isfahan (Iran); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Mihrab in the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan; this mihrab dates in its present state from the 9th century, Kairouan, Tunisia

Mihrab in the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan; this mihrab dates in its present state from the 9th century, Kairouan, Tunisia

-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Chain_(Mihrab).jpg.webp) Mihrab in the Dome of the Chain, Temple Mount, Jerusalem.

Mihrab in the Dome of the Chain, Temple Mount, Jerusalem. Mihrab in the Qila-i-Kuhna Mosque, in Delhi

Mihrab in the Qila-i-Kuhna Mosque, in Delhi Mihrab in the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, in Roxbury, Boston.

Mihrab in the Islamic Society of Boston Cultural Center, in Roxbury, Boston.

This mihrab is from a shrine at the tomb of Imamzada Yayha in Veramin, Iran and now is installed at a museum in Hawaii.

This mihrab is from a shrine at the tomb of Imamzada Yayha in Veramin, Iran and now is installed at a museum in Hawaii.

Notes

- K. A. C. Creswell and some later scholars argued that the oldest surviving mihrab is a flat marble panel, known as the Mihrab of Sulayman, found in the rock-cut chamber under the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which he attributed to the construction of Abd al-Malik in the late 7th century.[11] However, more recent scholarship has dated this mihrab to the 9th or 10th centuries based on stylistic, paleographic, and other historical grounds.[2] Flat mihrabs were occasionally popular in these periods under the Tulunid and Fatimid dynasties.[11][2]

References

- Khoury, Nuha N. N. (1998). "The Mihrab: From Text to Form". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 30 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0020743800065545. S2CID 161470520.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Mihrab". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Peeters Publishers. p. 224. ISBN 978-90-429-0815-4. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- Biella, Joan Copeland (2018). Dictionary of Old South Arabic, Sabaean Dialect. BRILL. ISBN 9789004369993.

- American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language - mihrabs (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2016. ISBN 978-0544454453.

- Dillmann, August; Munzinger, Werner (1865). Lexicon linguae aethiopicae cum indice latino. Lipsiae, T.O. Weigel. pp. 835–836. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- Nöldeke, Theodor (1910). Neue Beiträge zur semitischen Sprachwissenschaft / von Theodor Nöldeke. Straßburg: Karl J. Trübner. p. 52. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- "Semitic Roots Repository - View Root". www.semiticroots.net. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- Sheikho, Mohammad Amin (October 2011). Unveiling the Secrets of Magic and Magicians. Amin-sheikho.com. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- Kuban, Doğan (1974). Muslim Religious Architecture, Part I: The Mosque and Its Early Development. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-03813-4.

- Fehérvári, G. (1960–2007). "Miḥrāb". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088670.

- Brend, Barbara (1991). Islamic Art. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-46866-5.

- Rogers, J. M. (2008). The arts of Islam : treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili collection (Revised and expanded ed.). Abu Dhabi: Tourism Development & Investment Company (TDIC). p. 295. OCLC 455121277.

- Khalili, Nasser D. (2005). The timeline history of Islamic art and architecture. London: Worth. p. 117. ISBN 1-903025-17-6. OCLC 61177501.

- "Masjid al-Qiblatain - Madain Project (en)". madainproject.com. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- Terasaki, Steffie. "Mihrab". courses.washington.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "Mihrab". Mihrab. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "Mezquita de Córdoba | The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century". Archnet. p. 83. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Sheila S., Blair (2009). Bloom, Jonathan M; Blair, Sheila S (eds.). "The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195309911.001.0001. ISBN 9780195309911. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Grafman, Rafi; Rosen-Ayalon, Myriam (1999). "The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus". Muqarnas. 16: 8. doi:10.2307/1523262. JSTOR 1523262.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2001). The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Ummayyad Visual Culture. BRILL. ISBN 9789004116382.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (1997). "Umayyad Survivals and Mamluk Revivals: Qalawunid Architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus". Muqarnas. Boston: Brill. 14: 57–79. doi:10.2307/1523236. JSTOR 1523236.