Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew (עִבְרִית חֲדָשָׁה ʿĪvrīt ḥadašá [ivˈʁit χadaˈʃa]), also called Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. Developed as part of Hebrew's revival in the late 19th century and early 20th century, it is the official language of the State of Israel. It is the world's only Canaanite language that is still in use.[7]

| Modern Hebrew | |

|---|---|

| "Hebrew" / "Israeli Hebrew" | |

| עברית חדשה | |

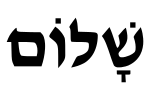

Render of the word "shalom" in Modern Hebrew, including vowel diacritics | |

| Region | Southern Levant |

| Ethnicity | Jews |

Native speakers | 9 million (2014)[1][2][3] |

Early forms | |

| Hebrew alphabet Hebrew Braille | |

| Signed Hebrew (national form)[4] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academy of the Hebrew Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | he |

| ISO 639-2 | heb |

| ISO 639-3 | heb |

| Glottolog | hebr1245 |

| |

Spoken since antiquity, Hebrew, a Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic language family, was the vernacular of the Jewish people until the 3rd century BCE, when it was supplanted by Western Aramaic, a dialect of the Aramaic language. However, it continued to be used for Jewish liturgy and for some genres of Jewish literature. By the late 19th century, Russian-Jewish linguist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda had begun a popular movement to revive Hebrew as a living language, motivated by his desire to preserve Hebrew literature and a distinct Jewish nationality in the context of Zionism.[8][9][10]

Currently, Hebrew is spoken by approximately 9–10 million people, counting native, fluent, and non-fluent speakers.[11][12] Half of this figure comprises Israelis who speak it as their native language, while the other half is split: 1.5 million are immigrants to Israel; 1.5 million are Israeli Arabs, whose first language is usually Arabic; and half a million are expatriate Israelis or diaspora Jews.

Under Israeli law, the organization that officially directs the development of Modern Hebrew is the Academy of the Hebrew Language, headquartered at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Name

The most common scholarly term for the language is "Modern Hebrew" (עברית חדשה ʿivrít ħadašá[h]). Most people refer to it simply as Hebrew (עברית Ivrit).[13]

The term "Modern Hebrew" has been described as "somewhat problematic"[14] as it implies unambiguous periodization from Biblical Hebrew.[14] Haiim B. Rosén (חיים רוזן) supported the now widely used[14] term "Israeli Hebrew" on the basis that it "represented the non-chronological nature of Hebrew".[13][15] In 1999, Israeli linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann proposed the term "Israeli" to represent the multiple origins of the language.[16]: 325 [13]

Background

The history of the Hebrew language can be divided into four major periods:[17]

- Biblical Hebrew, until about the 3rd century BCE; the language of most of the Hebrew Bible

- Mishnaic Hebrew, the language of the Mishnah and Talmud

- Medieval Hebrew, from about the 6th to the 13th century CE

- Modern Hebrew, the language of the modern State of Israel

Jewish contemporary sources describe Hebrew flourishing as a spoken language in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, during about 1200 to 586 BCE.[18] Scholars debate the degree to which Hebrew remained a spoken vernacular following the Babylonian captivity, when Old Aramaic became the predominant international language in the region.

Hebrew died out as a vernacular language somewhere between 200 and 400 CE, declining after the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136 CE, which devastated the population of Judea. After the exile, Hebrew became restricted to liturgical use.[19]

Revival

Hebrew had been spoken at various times and for a number of purposes throughout the Diaspora, and during the Old Yishuv it had developed into a spoken lingua franca among the Jews of Palestine.[20] Eliezer Ben-Yehuda then led a revival of the Hebrew language as a mother tongue in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Modern Hebrew used Biblical Hebrew morphemes, Mishnaic spelling and grammar, and Sephardic pronunciation. Many idioms and calques were made from Yiddish. Its acceptance by the early Jewish immigrants to Ottoman Palestine was caused primarily by support from the organisations of Edmond James de Rothschild in the 1880s and the official status it received in the 1922 constitution of the British Mandate for Palestine.[21][22][23][24] Ben-Yehuda codified and planned Modern Hebrew using 8,000 words from the Bible and 20,000 words from rabbinical commentaries. Many new words were borrowed from Arabic, due to the language's common Semitic roots with Hebrew, but changed to fit Hebrew phonology and grammar, for example the words gerev (sing.) and garbayim (pl.) are now applied to 'socks', a diminutive of the Arabic ğuwārib ('socks').[25][26] In addition, early Jewish immigrants, borrowing from the local Arabs, and later immigrants from Arab lands introduced many nouns as loanwords from Arabic (such as nana, zaatar, mishmish, kusbara, ḥilba, lubiya, hummus, gezer, rayḥan, etc.), as well as much of Modern Hebrew's slang. Despite Ben-Yehuda's fame as the renewer of Hebrew, the most productive renewer of Hebrew words was poet Haim Nahman Bialik.

One of the phenomena seen with the revival of the Hebrew language is that old meanings of nouns were occasionally changed for altogether different meanings, such as bardelas (ברדלס), which in Mishnaic Hebrew meant 'hyena',[27] but in Modern Hebrew it now means 'cheetah'; or shezīph (שְׁזִיף) which is now used for 'plum', but formerly meant 'jujube'.[28] The word kishū’īm (formerly 'cucumbers')[29] is now applied to a variety of summer squash (Cucurbita pepo var. cylindrica), a plant native to the New World. Another example is the word kǝvīš (כביש), which now denotes a street or a road, but is actually an Aramaic adjective meaning 'trodden down' or 'blazed', rather than a common noun. It was originally used to describe a blazed trail.[30][31] The flower Anemone coronaria, called in Modern Hebrew kalanit, was formerly called in Hebrew shoshanat ha-melekh ('the king's flower').[32][33]

For a simple comparison between the Sephardic and Yemenite versions of Mishnaic Hebrew, see Yemenite Hebrew.

Classification

Modern Hebrew is classified as an Afroasiatic language of the Semitic family, the Canaanite branch of the Northwest Semitic subgroup.[34][35][36][37] While Modern Hebrew is largely based on Mishnaic and Biblical Hebrew as well as Sephardi and Ashkenazi liturgical and literary tradition from the Medieval and Haskalah eras and retains its Semitic character in its morphology and in much of its syntax,[38][39] the consensus among scholars is that Modern Hebrew represents a fundamentally new linguistic system, not directly continuing any previous linguistic state.[40]

Modern Hebrew is considered to be a koiné language based on historical layers of Hebrew that incorporates foreign elements, mainly those introduced during the most critical revival period between 1880 and 1920, as well as new elements created by speakers through natural linguistic evolution.[40][34] A minority of scholars argue that the revived language had been so influenced by various substrate languages that it is genealogically a hybrid with Indo-European.[41][42][43][44] Those theories have not been met with general acceptance, and the consensus among a majority of scholars is that Modern Hebrew, despite its non-Semitic influences, can correctly be classified as a Semitic language.[35][45] Although European languages have had an impact on Modern Hebrew, the impact may often be overstated. Although Modern Hebrew has more of the features attributed to Standard Average European than Biblical Hebrew, it is still quite distant, and has fewer such features than Modern Standard Arabic.[46]

Alphabet

Modern Hebrew is written from right to left using the Hebrew alphabet, which is an abjad, or consonant-only script of 22 letters based on the "square" letter form, known as Ashurit (Assyrian), which was developed from the Aramaic script. A cursive script is used in handwriting. When necessary, vowels are indicated by diacritic marks above or below the letters known as Nikkud, or by use of Matres lectionis, which are consonantal letters used as vowels. Further diacritics like Dagesh and Sin and Shin dots are used to indicate variations in the pronunciation of the consonants (e.g. bet/vet, shin/sin). The letters "צ׳", "ג׳", "ז׳", each modified with a Geresh, represent the consonants [t͡ʃ], [d͡ʒ], [ʒ]. The consonant [t͡ʃ] may also be written as "תש" and "טש". [w] is represented interchangeably by a simple vav "ו", non-standard double vav "וו" and sometimes by non-standard geresh modified vav "ו׳".

| Name | Alef | Bet | Gimel | Dalet | He | Vav | Zayin | Chet | Tet | Yod | Kaf | Lamed | Mem | Nun | Samech | Ayin | Pe | Tzadi | Kof | Resh | Shin | Tav |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printed letter | א | ב | ג | ד | ה | ו | ז | ח | ט | י | כ | ל | מ | נ | ס | ע | פ | צ | ק | ר | ש | ת |

| Cursive letter | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation | [ʔ], ∅ | [b], [v] | [g] | [d] | [h] | [v] | [z] | [x]~[χ] | [t] | [j] | [k], [x]~[χ] | [l] | [m] | [n] | [s] | [ʔ], ∅ | [p], [f] | [t͡s] | [k] | [ɣ]~[ʁ] | [ʃ], [s] | [t] |

| Transliteration | a,e,i,o,u,' | b, v | g | d | h | v | z | h, ch | t | y | k, kh | l | m | n | s | a,e,i,o,u,' | p, f | ts | k | r | sh, s | t |

Phonology

Modern Hebrew has fewer phonemes than Biblical Hebrew but it has developed its own phonological complexity. Israeli Hebrew has 25 to 27 consonants, depending on whether the speaker has pharyngeals. It has 5 to 10 vowels, depending on whether diphthongs and long and short vowels are counted, varying with the speaker and the analysis.

This table lists the consonant phonemes of Israeli Hebrew in IPA transcription:[2]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palato-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstru- ents |

Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ʔ2 | |||||||

| Affricate | t͡s | (t͡ʃ)5 | (d͡ʒ)4 | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | (ʒ)4 | x~χ1 | ɣ~ʁ3 | h2 | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | (w)4 | ||||||||||||

- 1 In modern Hebrew /ħ/ for ח has been absorbed by /x~χ/ that was traditionally only for fricative כ, but some (mainly older) Mizrahi speakers still separate them.[47]

- 2 The glottal consonants are elided in most unstressed syllables and sometimes also in stressed syllables, but they are pronounced in careful or formal speech. In modern Hebrew, /ʕ/ for ע has merged with /ʔ/ (א), but some speakers (particularly older Mizrahi speakers) still separate them.[47]

- 3 Commonly transcribed /r/. This is usually pronounced as a uvular fricative or approximant [ʁ] or velar fricative [ɣ], and sometimes as a uvular [ʀ] or alveolar trill [r] or alveolar flap [ɾ], depending on the background of the speaker.[47]

- 4 The phonemes /w, dʒ, ʒ/ were introduced through borrowings.

- 5 The phoneme /tʃ/ צ׳ was introduced through borrowings,[48] but it can appear in native words as a sequence of /t/ ת and /ʃ/ שׁ as in תְּשׁוּקָה /tʃuˈka/.

Obstruents often assimilate in voicing: voiceless obstruents (/p t ts tʃ k, f s ʃ x/) become voiced ([b d dz dʒ ɡ, v z ʒ ɣ]) when they appear immediately before voiced obstruents, and vice versa.

Hebrew has five basic vowel phonemes:

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i | u | |

| mid | e | o | |

| low | a |

Long vowels occur unpredictably if two identical vowels were historically separated by a pharyngeal or glottal consonant, and the first was stressed.

Any of the five short vowels may be realized as a schwa [ə] when it is far from lexical stress.

There are two diphthongs, /aj/ and /ej/.[2]

Most lexical words have lexical stress on one of the last two syllables, the last syllable being more frequent in formal speech. Loanwords may have stress on the antepenultimate syllable or even earlier.

Pronunciation

While the pronunciation of Modern Hebrew is based on Sephardi Hebrew, the pronunciation has been affected by the immigrant communities that have settled in Israel in the past century and there has been a general coalescence of speech patterns. The pharyngeal [ħ] for the phoneme chet (ח) of Sephardi Hebrew has merged into [χ], which Sephardi Hebrew only used for fricative chaf (כ). The pronunciation of the phoneme ayin (ע) has merged with the pronunciation of aleph (א), which is either [ʔ] or unrealized [∅] and has come to dominate Modern Hebrew, but in many variations of liturgical Sephardi Hebrew, it is [ʕ], a voiced pharyngeal fricative. The letter vav (ו) is realized as [v], which is the standard for both Ashkenazi and most variations of Sephardi Hebrew. The Jews of Iraq, Aleppo, Yemen and some parts of North Africa pronounced vav as [w]. Yemenite Jews, during their liturgical readings in the synagogues, still use the latter, older pronunciation. The pronunciation of the letter resh (ר) has also largely shifted from Sephardi [r] to either [ɣ] or [ʁ].

Morphology

Modern Hebrew morphology (formation, structure, and interrelationship of words in a language) is essentially Biblical.[49] Modern Hebrew showcases much of the inflectional morphology of the classical upon which it was based. In the formation of new words, all verbs and the majority of nouns and adjectives are formed by the classically Semitic devices of triconsonantal roots (shoresh) with affixed patterns (mishkal). Mishnaic attributive patterns are often used to create nouns, and Classical patterns are often used to create adjectives. Blended words are created by merging two bound stems or parts of words.

Syntax

The syntax of Modern Hebrew is mainly Mishnaic[49] but also shows the influence of different contact languages to which its speakers have been exposed during the revival period and over the past century.

Word order

The word order of Modern Hebrew is predominately SVO (subject–verb–object). Biblical Hebrew was originally verb–subject–object (VSO), but drifted into SVO.[50] Modern Hebrew maintains classical syntactic properties associated with VSO languages: it is prepositional, rather than postpositional, in making case and adverbial relations, auxiliary verbs precede main verbs; main verbs precede their complements, and noun modifiers (adjectives, determiners other than the definite article ה-, and noun adjuncts) follow the head noun; and in genitive constructions, the possessee noun precedes the possessor. Moreover, Modern Hebrew allows and sometimes requires sentences with a predicate initial.

Lexicon

Modern Hebrew has expanded its vocabulary effectively to meet the needs of casual vernacular, of science and technology, of journalism and belles-lettres. According to Ghil'ad Zuckermann:

The number of attested Biblical Hebrew words is 8198, of which some 2000 are hapax legomena (the number of Biblical Hebrew roots, on which many of these words are based, is 2099). The number of attested Rabbinic Hebrew words is less than 20,000, of which (i) 7879 are Rabbinic par excellence, i.e. they did not appear in the Old Testament (the number of new Rabbinic Hebrew roots is 805); (ii) around 6000 are a subset of Biblical Hebrew; and (iii) several thousand are Aramaic words which can have a Hebrew form. Medieval Hebrew added 6421 words to (Modern) Hebrew. The approximate number of new lexical items in Israeli is 17,000 (cf. 14,762 in Even-Shoshan 1970 [...]). With the inclusion of foreign and technical terms [...], the total number of Israeli words, including words of biblical, rabbinic and medieval descent, is more than 60,000.[51]: 64–65

Loanwords

Modern Hebrew has loanwords from Arabic (both from the local Palestinian dialect and from the dialects of Jewish immigrants from Arab countries), Aramaic, Yiddish, Judaeo-Spanish, German, Polish, Russian, English and other languages. Simultaneously, Israeli Hebrew makes use of words that were originally loanwords from the languages of surrounding nations from ancient times: Canaanite languages as well as Akkadian. Mishnaic Hebrew borrowed many nouns from Aramaic (including Persian words borrowed by Aramaic), as well as from Greek and to a lesser extent Latin.[52] In the Middle Ages, Hebrew made heavy semantic borrowing from Arabic, especially in the fields of science and philosophy. Here are typical examples of Hebrew loanwords:

| loanword | derivatives | origin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | IPA | meaning | Hebrew | IPA | meaning | language | spelling | meaning |

| ביי | /baj/ | goodbye | English | bye | ||||

| אגזוז | /eɡˈzoz/ | exhaust system | exhaust system | |||||

| דיג׳יי | /ˈdidʒej/ | DJ | דיג׳ה | /diˈdʒe/ | to DJ | to DJ | ||

| ואללה | /ˈwala/ | really!? | Arabic | والله | really!? | |||

| כיף | /kef/ | fun | כייף | /kiˈjef/ | to have fun[w 1] | كيف | pleasure | |

| תאריך | /taʔaˈriχ/ | date | תארך | /teʔeˈreχ/ | to date | تاريخ | date, history | |

| חנון | /χnun/ | geek, wimp, nerd, "square" | Moroccan Arabic | خنونة | snot | |||

| אבא | /ˈaba/ | dad | Aramaic | אבא | the father/my father | |||

| דוּגרִי | /ˈdugri/ | forthright | Ottoman Turkish | طوغری doğrı | correct | |||

| פרדס | /parˈdes/ | orchard | Avestan | 𐬞𐬀𐬌𐬭𐬌⸱𐬛𐬀𐬉𐬰𐬀 | garden | |||

| אלכסון | /alaχˈson/ | diagonal | Greek | λοξός | slope | |||

| וילון | /viˈlon/ | curtain | Latin | vēlum | veil, curtain | |||

| חלטורה | /χalˈtura/ | shoddy job | חלטר | /χilˈteʁ/ | to moonlight | Russian | халтура | shoddy work[w 2] |

| בלגן | /balaˈɡan/ | mess | בלגן | /bilˈɡen/ | to make a mess | балаган | chaos[w 2] | |

| תכל׳ס | /ˈtaχles/ | directly/ essentially | Yiddish | תכלית | goal (Hebrew word, only pronunciation is Yiddish) | |||

| חרופ | /χʁop/ | deep sleep | חרפ | /χaˈʁap/ | to sleep deeply | כראָפ | snore | |

| שפכטל | /ˈʃpaχtel/ | putty knife | German | Spachtel | putty knife | |||

| גומי | /ˈɡumi/ | rubber | גומיה | /ɡumiˈja/ | rubber band | Gummi | rubber | |

| גזוז | /ɡaˈzoz/ | carbonated beverage | Turkish from French | gazoz[w 3] from eau gazeuse | carbonated beverage | |||

| פוסטמה | /pusˈtema/ | stupid woman | Ladino | פּוֹשׂטֵימה postema | inflamed wound[w 4] | |||

| אדריכל | /adʁiˈχal/ | architect | אדריכלות | /adʁiχaˈlut/ | architecture | Akkadian | 𒀵𒂍𒃲 | temple servant[w 5] |

| צי | /t͡si/ | fleet | Ancient Egyptian | ḏꜣy | ship | |||

- bitFormation. "Loanwords in Hebrew from Arabic". Safa-ivrit.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- bitFormation. "Loanwords in Hebrew from Russian". Safa-ivrit.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- bitFormation. "Loanwords in Hebrew from Turkish". Safa-ivrit.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- bitFormation. "Loanwords in Hebrew from Ladino". Safa-ivrit.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2005. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- אתר השפה העברית. "Loanwords in Hebrew from Akkadian". Safa-ivrit.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

See also

References

- "Hebrew". UCLA Language Materials Project. University of California. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Dekel 2014

- "Hebrew". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Meir & Sandler, 2013, A Language in Space: The Story of x Sign Language

- אוכלוסייה, לפי קבוצת אוכלוסייה, דת, גיל ומין, מחוז ונפה [Population, by Population Group, Religion, age and sex, district and sub-district] (PDF) (in Hebrew). Central Bureau of Statistics. 6 September 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "The Arab Population in Israel" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. November 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Huehnergard, John; Pat-El, Na'ama (2019). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. p. 571. ISBN 9780429655388. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Mandel, George (2005). "Ben-Yehuda, Eliezer [Eliezer Yizhak Perelman] (1858–1922)". Encyclopedia of modern Jewish culture. Glenda Abramson ([New ed.] ed.). London. ISBN 0-415-29813-X. OCLC 57470923. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

In 1879 he wrote an article for the Hebrew press advocating Jewish immigration to Palestine. Ben-Yehuda argued that only in a country with a Jewish majority could a living Hebrew literature and a distinct Jewish nationality survive; elsewhere, the pressure to assimilate to the language of the majority would cause Hebrew to die out. Shortly afterwards he reached the conclusion that the active use of Hebrew as a literary language could not be sustained, notwithstanding the hoped-for concentration of Jews in Palestine, unless Hebrew also became the everyday spoken language there.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fellman, Jack (19 July 2011). The Revival of Classical Tongue : Eliezer Ben Yehuda and the Modern Hebrew Language. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-087910-0. OCLC 1089437441. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- Kuzar, Ron (2001), Hebrew and Zionism, Berlin, Boston: DE GRUYTER, doi:10.1515/9783110869491.vii, archived from the original on 1 July 2023, retrieved 10 May 2023

- Klein, Zeev (18 March 2013). "A million and a half Israelis struggle with Hebrew". Israel Hayom. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Nachman Gur; Behadrey Haredim. "Kometz Aleph – Au• How many Hebrew speakers are there in the world?". Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Dekel 2014; quote: "Most people refer to Israeli Hebrew simply as Hebrew. Hebrew is a broad term, which includes Hebrew as it was spoken and written in different periods of time and according to most of the researchers as it is spoken and written in Israel and elsewhere today. Several names have been proposed for the language spoken in Israel nowadays, Modern Hebrew is the most common one, addressing the latest spoken language variety in Israel (Berman 1978, Saenz-Badillos 1993:269, Coffin-Amir & Bolozky 2005, Schwarzwald 2009:61). The emergence of a new language in Palestine at the end of the nineteenth century was associated with debates regarding the characteristics of that language.... Not all scholars supported the term Modern Hebrew for the new language. Rosén (1977:17) rejected the term Modern Hebrew, since linguistically he claimed that 'modern' should represent a linguistic entity that should command autonomy towards everything that preceded it, while this was not the case in the new emerging language. He also rejected the term Neo-Hebrew, because the prefix 'neo' had been previously used for Mishnaic and Medieval Hebrew (Rosén 1977:15–16), additionally, he rejected the term Spoken Hebrew as one of the possible proposals (Rosén 1977:18). Rosén supported the term Israeli Hebrew as in his opinion it represented the non-chronological nature of Hebrew, as well as its territorial independence (Rosén 1977:18). Rosén then adopted the term Contemporary Hebrew from Téne (1968) for its neutrality, and suggested the broadening of this term to Contemporary Israeli Hebrew (Rosén 1977:19)"

- Matras & Schiff 2005; quote: The language with which we are concerned in this contribution is also known by the names Contemporary Hebrew and Modern Hebrew, both somewhat problematic terms as they rely on the notion of an unambiguous periodization separating Classical or Biblical Hebrew from the present-day language. We follow instead the now widely-used label coined by Rosén (1955), Israeli Hebrew, to denote the link between the emergence of a Hebrew vernacular and the emergence of an Israeli national identity in Israel/Palestine in the early twentieth century."

- Haiim Rosén (1 January 1977). Contemporary Hebrew. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-3-11-080483-6.

- Zuckermann, G. (1999), "Review of the Oxford English-Hebrew Dictionary", International Journal of Lexicography, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 325-346

- Hebrew language Archived 2015-06-11 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica

- אברהם בן יוסף ,מבוא לתולדות הלשון העברית (Avraham ben-Yosef, Introduction to the History of the Hebrew Language), page 38, אור-עם, Tel Aviv, 1981.

- Sáenz-Badillos, Ángel and John Elwolde: "There is general agreement that two main periods of RH (Rabbinical Hebrew) can be distinguished. The first, which lasted until the close of the Tannaitic era (around 200 CE), is characterized by RH as a spoken language gradually developing into a literary medium in which the Mishnah, Tosefta, baraitot and Tannaitic midrashim would be composed. The second stage begins with the Amoraim and sees RH being replaced by Aramaic as the spoken vernacular, surviving only as a literary language. Then it continued to be used in later rabbinic writings until the tenth century in, for example, the Hebrew portions of the two Talmuds and in midrashic and haggadic literature."

- Tudor Parfitt; The Contribution of the old Yishuv to the Revival of Hebrew, Journal of Semitic Studies, Volume XXIX, Issue 2, 1 October 1984, Pages 255–265, https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/XXIX.2.255 Archived 2023-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Hobsbawm, Eric (2012). Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-39446-9., "What would the future of Hebrew have been, had not the British Mandate in 1919 accepted it as one of the three official languages of Palestine, at a time when the number of people speaking Hebrew as an everyday language was less than 20,000?"

- Swirski, Shlomo (11 September 2002). Politics and Education in Israel: Comparisons with the United States. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-58242-5.: "In retrospect, [Hobsbawm's] question should be rephrased, substituting the Rothschild house for the British state and the 1880s for 1919. For by the time the British conquered Palestine, Hebrew had become the everyday language of a small but well-entrenched community."

- Palestine Mandate (1922): "English, Arabic and Hebrew shall be the official languages of Palestine"

- Benjamin Harshav (1999). Language in Time of Revolution. Stanford University Press. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-0-8047-3540-7.

- Even-Shoshan, A., ed. (2003). Even-Shoshan Dictionary (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. ha-Milon he-ḥadash Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 965-517-059-4. OCLC 55071836.

- Cf. Rabbi Hai Gaon's commentary on Mishnah Kelim 27:6, where אמפליא (ampalya) was used formerly for the same, and had the equivalent meaning of the Arabic word ğuwārib ('stockings'; 'socks').

- Maimonides' commentary and Rabbi Ovadiah of Bartenura's commentary on Mishnah Baba Kama 1:4; Rabbi Nathan ben Abraham's Mishnah Commentary, Baba Metzia 7:9, s.v. הפרדלס; Sefer Arukh, s.v. ברדלס; Zohar Amar, Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings, Kefar Darom 2015, pp. 177–178; 228

- Zohar Amar, Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings, Kfar Darom 2015, p. 157, s.v. שזפין OCLC 783455868, explained to mean 'jujube' (Ziziphus jujuba); Solomon Sirilio's Commentary of the Jerusalem Talmud, on Kila'im 1:4, s.v. השיזפין, which he explained to mean in Spanish azufaifas ('jujubes'). See also Saul Lieberman, Glossary in Tosephta - based on the Erfurt and Vienna Codices (ed. M.S. Zuckermandel), Jerusalem 1970, s.v. שיזפין (p. LXL), explained in German as meaning Brustbeerbaum ('jujube').

- Thus explained by Maimonides in his Commentary on Mishnah Kila'im 1:2 and in Mishnah Terumot 2:6. See: Zohar Amar, Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings, Kefar Darom 2015, pp. 111, 149 (Hebrew) OCLC 783455868; Zohar Amar, Agricultural Produce in the Land of Israel in the Middle Ages (Hebrew title: גידולי ארץ-ישראל בימי הביניים), Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 2000, p. 286 ISBN 965-217-174-3 (Hebrew)

- Compare Rashi's commentary on Exodus 9:17, where he says the word mesillah is translated in Aramaic oraḥ kevīsha ('a blazed trail'), the word kevīsh being only an adjective or descriptive word, but not a common noun as it is used today. It is said that Ze'ev Yavetz (1847–1924) is the one who coined this modern Hebrew word for 'road'. See Haaretz, Contributions made by Ze'ev Yavetz Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine; Maltz, Judy (25 January 2013). "With Tu Bishvat Near, a Tree Grows in Zichron Yaakov". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Roberto Garvio, Esperanto and its Rivals, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 164

- Amar, Z. (2015). Flora and Fauna in Maimonides' Teachings (in Hebrew). Kfar Darom. p. 156. OCLC 783455868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), s.v. citing Maimonides on Mishnah Kil'ayim 5:8 - Matar – Science and Technology On-line, the Common Anemone (in Hebrew)

- Hebrew at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Weninger, Stefan, Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet CE Watson, Gábor Takács, Vermondo Brugnatelli, H. Ekkehard Wolff et al. The Semitic Languages. An International Handbook. Berlin–Boston (2011).

- Robert Hetzron (1997). The Semitic Languages. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415057677. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Hadumod Bussman (2006). Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 9781134630387.

- Robert Hetzron. (1987). "Hebrew". In The World's Major Languages, ed. Bernard Comrie, 686–704. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Patrick R. Bennett (1998). Comparative Semitic Linguistics: A Manual. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060217. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Reshef, Yael. Revival of Hebrew: Grammatical Structure and Lexicon. Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. (2013).

- Olga Kapeliuk (1996). "Is Modern Hebrew the only "Indo-Europeanied" Semitic Language? And what about Neo-Aramaic?". In Shlomo Izre'el; Shlomo Raz (eds.). Studies in Modern Semitic Languages. Israel Oriental Studies. BRILL. p. 59. ISBN 9789004106468.

- Wexler, Paul, The Schizoid Nature of Modern Hebrew: A Slavic Language in Search of a Semitic Past: 1990.

- Izre'el, Shlomo (2003). "The Emergence of Spoken Israeli Hebrew." In: Benjamin H. Hary (ed.), Corpus Linguistics and Modern Hebrew: Towards the Compilation of The Corpus of Spoken Israeli Hebrew (CoSIH)", Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, The Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies, 2003, pp. 85–104.

- See p. 62 in Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2006), "A New Vision for 'Israeli Hebrew': Theoretical and Practical Implications of Analysing Israel's Main Language as a Semi-Engineered Semito-European Hybrid Language", Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 5 (1), pp. 57–71.

- Yael Reshef. "The Re-Emergence of Hebrew as a National Language" in Weninger, Stefan, Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet CE Watson, Gábor Takács, Vermondo Brugnatelli, H. Ekkehard Wolff et al. (eds) The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin–Boston (2011). p. 551

- Amir Zeldes (2013). "Is Modern Hebrew Standard Average European? The View from European" (PDF). Linguistic Typology. 17 (3): 439–470. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- Dekel 2014.

- Bolozky, Shmuel (1997). "Israeli Hebrew phonology". Israeli Hebrew Phonology. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- R. Malatesha Joshi; P. G. Aaron, eds. (2013). Handbook of Orthography and Literacy. Routledge. p. 343. ISBN 9781136781353. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Li, Charles N. Mechanisms of Syntactic Change. Austin: U of Texas, 1977. Print.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232 Archived 2019-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- The Latin "familia", from which English "family" is derived, entered Mishnaic Hebrew - and thence, Modern Hebrew - as "pamalya" (פמליה) meaning "entourage". (The original Latin "familia" referred both to a prominent Roman's family and to his household in general, including the entourage of slaves and freedmen which accompanied him in public - hence, both the English and the Hebrew one are derived from the Latin meaning.)

Bibliography

- Choueka, Yaakov (1997). Rav-Milim: A comprehensive dictionary of Modern Hebrew. Tel Aviv: CET. ISBN 978-965-448-323-0.

- Ben-Ḥayyim, Ze'ev (1992). The Struggle for a Language. Jerusalem: The Academy of the Hebrew Language.

- Dekel, Nurit (2014). Colloquial Israeli Hebrew: A Corpus-based Survey. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-037725-5.

- Gila Freedman Cohen; Carmia Shoval (2011). Easing Into Modern Hebrew Grammar: A User-friendly Reference and Exercise Book. Magnes Press. ISBN 978-965-493-601-9.

- Shlomo Izreʾel; Shlomo Raz (1996). Studies in Modern Semitic Languages. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10646-8.

- Matras, Yaron; Schiff, Leora (2005). "Spoken Israeli Hebrew revisited: Structures and variation" (PDF). Studia Semitica. 16: 145–193.

- Ornan, Uzzi (2003). "The Final Word: Mechanism for Hebrew Word Generation". Hebrew Studies. Haifa University. 45: 285–287. JSTOR 27913706.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf (1983). Peter T. Daniels (ed.). Introduction to the Semitic Languages: Text Specimens and Grammatical Sketches. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0-931464-10-2.

- Haiim B. Rosén [in Hebrew] (1962). A Textbook of Israeli Hebrew. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72603-8.

- Stefan Weninger (23 December 2011). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Wexler, Paul (1990). The Schizoid Nature of Modern Hebrew: A Slavic Language in Search of a Semitic Past. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03063-2.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

External links

- Modern Hebrew Swadesh list

- The Corpus of Spoken Israeli Hebrew - introduction by Tel Aviv University

- Hebrew Today – Should You Learn Modern Hebrew or Biblical Hebrew?

- History of the Ancient and Modern Hebrew Language by David Steinberg

- Short History of the Hebrew Language by Chaim Menachem Rabin

- Academy of the Hebrew Language: How a Word is Born