Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (usually referred to as the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, abbreviated MUTCD) is a document issued by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) of the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) to specify the standards by which traffic signs, road surface markings, and signals are designed, installed, and used. In the United States, all traffic control devices must legally conform to these standards. The manual is used by state and local agencies as well as private construction firms to ensure that the traffic control devices they use conform to the national standard. While some state agencies have developed their own sets of standards, including their own MUTCDs, these must substantially conform to the federal MUTCD.

Cover of the 2009 edition | |

| Authors |

|

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Published | August 2022 (2009 edition with Revisions 1, 2 and 3) |

| Publisher | Federal Highway Administration |

Publication date | 1935 |

| ISBN | 9781560514732 |

| OCLC | 777002425 |

| Website | mutcd |

The MUTCD defines the content and placement of traffic signs, while design specifications are detailed in a companion volume, Standard Highway Signs and Markings. This manual defines the specific dimensions, colors, and fonts of each sign and road marking. The National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD) advises the FHWA on additions, revisions, and changes to the MUTCD.

The United States is among the countries that have not ratified the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals. The first edition of the MUTCD was published in 1935, 33 years before the Vienna Convention was signed in 1968. The MUTCD differs significantly from the European-influenced Vienna Convention, and an attempt to adopt several of the Vienna Convention's standards during the 1970s led to confusion among many US drivers.

History

At the start of the 20th century—the early days of the rural highway—each road was promoted and maintained by automobile clubs of private individuals, who generated revenue through club membership and increased business along cross-country routes. However, each highway had its own set of signage, usually designed to promote the highway rather than to assist in the direction and safety of travelers. In fact, conflicts between these automobile clubs frequently led to multiple sets of signs—sometimes as many as eleven—being erected on the same highway.

Government action to begin resolving the wide variety of signage that had cropped up did not occur until the late 1910s and early 1920s when groups from Indiana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin began surveying existing road signs in order to develop road signage standards. They reported their findings to the Mississippi Valley Association of Highway Departments, which adopted their suggestions in 1922 for the shapes to be used for road signs. These suggestions included the familiar circular railroad crossing sign and octagonal stop sign.[1]

In January 1927, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) published the Manual and Specifications for the Manufacture, Display, and Erection of U.S. Standard Road Markers and Signs to set standards for traffic control devices used on rural roads.[2] Despite the title, this manual did not have any guidance on pavement markings.[2] In the archaic American English of the 1920s, the term "road marker" was sometimes used to describe traffic control devices which modern speakers would now call "signs."[2] In 1930, the National Conference on Street and Highway Safety (NCSHS) published the Manual on Street Traffic Signs, Signals, and Markings, which set similar standards for urban settings, but also added specific guidance on traffic signals, pavement markings, and safety zones.[2] Although the two manuals were quite similar, both organizations immediately recognized that the existence of two slightly different manuals was unnecessarily awkward, and in 1931 AASHO and NCSHS formed a Joint Committee to develop a uniform standard for both urban streets and rural roads. This standard was the MUTCD.[1]

The original edition of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways was published in 1935.[1] Since that time, subsequent editions of the manual have been published with numerous minor updates occurring between, each taking into consideration changes in usage and size of the nation's system of roads as well as improvements in technology.

In 1942, the Joint Committee was expanded to include the Institute of Transportation Engineers, then known as the Institute of Traffic Engineers.[1] The single most controversial and heavily debated issue during the early years of the MUTCD was the color of center lines on roads. The 1948 version of the MUTCD settled the debate in favor of white, and also changed the standard color of stop signs from yellow to red.[2] However, the 1948 MUTCD also allowed for two major exceptions to white center lines: yellow was recommended but not mandatory for double center lines on multi-lane highways and for center lines in no-passing zones.[2]

In 1949, the United Nations Conference on Road and Motor Transport launched a research project to develop a worldwide uniform scheme for highway signs.[1] In 1951, the UN conducted experiments in the U.S. to compare the effectiveness of national traffic sign standards from around the world. Signs from six countries were placed along the road for test subjects to gauge their legibility at a distance.[3] The test strips were located along Ohio State Route 104 near Columbus,[4] U.S. Route 250 and Virginia State Route 53 near Charlottesville,[5] Minnesota State Highway 101 near Minneapolis,[6] and other roads in New York. France, Chile, Turkey, India, and Southern Rhodesia reciprocated by installing MUTCD signs on their roads.[7] In the U.S., the experiments attracted unexpected controversy and curious onlookers who posed a hazard.[8][9] By September 1951, the experts working on the project were in favor of the American proposals for stop signs (at the time, black "STOP" text on a yellow octagon), "cross road", "left or right curve", and "intersection", but were still struggling to reach consensus on symbols for "narrow road", "bumpy or uneven surface", and "steep hill".[10]

In 1953, after cooperating with the UN conference's initial experiments, the United States declined to sign or ratify the UN's then-proposed protocol for a worldwide system of uniform road signs.[1] There were two major reasons behind this decision.[1] First, most U.S. roads and streets were (and still are) under state jurisdiction.[1][7] Second, the United States was developing modern controlled-access highways at the time (culminating in the creation of the Interstate Highway System in 1956), and the novel problems presented by such new high-speed highways required rapid innovations in road signing and marking "that would definitely be impaired by adherence to any international code".[1] Despite the Americans' withdrawal from the research project, the experiments eventually resulted in the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals of 1968.

In 1960, the National Joint Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices was again reorganized to include representatives of the National Association of Counties and the National League of Cities, then known as the American Municipal Association.[1] In 1961, the MUTCD was again revised to make yellow center lines mandatory for the two exceptions where they had previously been recommended.[2] The 1961 edition was the first edition to provide for uniform signs and barricades to direct traffic around road construction and maintenance operations.[1]

In 1966, Congress passed the Highway Safety Act, Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 89–564, 72 Stat. 885, which is now codified at 23 U.S.C. § 401 et seq. It required all states to create a highway safety program by December 31, 1968, and to adhere to uniform standards promulgated by the U.S. Department of Transportation as a condition of receiving federal highway-aid funds.[11] The penalty for non-compliance was a 10% reduction in funding. In turn, taking advantage of broad rulemaking powers granted in 23 U.S.C. § 402, the Department simply adopted the entire MUTCD by reference at 23 CFR 655.603. (5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1), also enacted in 1966, authorizes federal agencies to incorporate by reference technical standards published elsewhere, which means the agency may merely cite the standard and need not republish its entire text as part of the appropriate regulation.) Thus, what was formerly a quasi-official project became an official one. States are allowed to supplement the MUTCD but must remain in "substantial conformance" with the national MUTCD and adopt changes within two years after they are adopted by FHWA.

The 1971 edition of the MUTCD included several significant standards. The MUTCD imposed a consistent color code for road surface markings by requiring all center lines dividing opposing traffic on two-way roads to be always painted in yellow (instead of white, which was to always demarcate lanes moving in the same direction),[2][12] and also required that all highway guide signs (not just those on Interstate Highways) contain white text on a green background.[13]

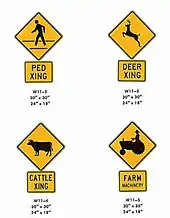

Another major change, inspired by the Vienna Convention,[14] was that the 1971 MUTCD expressed a preference for a transition to adoption of symbols on signs in lieu of words "as rapidly as public acceptance and other considerations permit."[15] During what was then expected to be a transition period, the MUTCD allowed state highway departments to use optional explanatory word plaques with symbol signs and to continue using the previous standard word message signs in certain cases.[15] Robert Conner, the chief of the traffic control systems division of the Federal Highway Administration during the 1970s, believed that symbol signs were "usually more effective than words in situations where reaction time and comprehension are important."[16] Conner was active in the Joint Committee and also represented the United States at international meetings on road traffic safety.[17] However, several American traffic safety experts were concerned that American drivers would not understand the Vienna Convention's unintuitive symbols, which is why the MUTCD allowed for explanatory word plaques.[18] Most of the repainting to the 1971 standard was done between 1971 and 1974, with a deadline of 1978 for the changeover of both the markings and signage.

The U.S. adoption of several Vienna Convention-inspired symbol signs during the 1970s was a failure. For example, the lane drop symbol sign was criticized as baffling to U.S. drivers—who saw a "big milk bottle"—and therefore quite dangerous, since by definition it was supposed to be used in situations where drivers were about to run out of road and needed to merge into another lane immediately.[19] American highway safety experts ridiculed it as the "Rain Ahead" sign.[19] Many American motorists were bewildered by the Vienna Convention's symbol sign with two children on it, requiring it to be supplemented with a "School Xing" plaque.[20] (The American "School Xing" symbol was later redesigned to depict an adult crossing together with a child.) The 1971 MUTCD's preference for a rapid transition to symbols over words quietly disappeared in the 1978 MUTCD.[21] The 2000 and 2003 MUTCDs each eliminated a symbol sign that had long been intended to replace a word message sign: "Pavement Ends" (in 2000) and "Narrow Bridge" (in 2003).[22]

On January 2, 2008, FHWA published a Notice of Proposed Amendment in the Federal Register containing a proposal for a new edition of the MUTCD, and published the draft content of this new edition on the MUTCD website for public review and comment. Comments were accepted until the end of July 2008.[23] The new edition was published in 2009. Revisions to the 2009 edition were then published in 2012.[24]

On December 14, 2020, FHWA published a notice of proposed amendment in the Federal Register containing a proposal for an 11th edition of the MUTCD, publishing the draft content of this new edition online for public review and comment until March 15, 2021.[25] The adoption of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in November 2021 also directed the USDOT to update the MUTCD by no later than May 15, 2023, and at least every four years thereafter.[26]

On May 15, 2023, despite provisions in the IIJA, the FHWA failed to release a new update to the MUTCD. The FHWA cited volume of comments as a reason for the delay.[27]

Development

Proposed additions and revisions to the MUTCD are recommended to FHWA by the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD), a private, non-profit organization. The NCUTCD also recommends interpretations of the MUTCD to other agencies that use the MUTCD, such as state departments of transportation. NCUTCD develops public and professional awareness of the principles of safe traffic control devices and practices and provides a forum for qualified individuals to exchange professional information.

The NCUTCD is supported by twenty-one sponsoring organizations, including transportation and engineering industry groups (such as AASHTO and ASCE), safety organizations (such as the National Safety Council and Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety), and the American Automobile Association. Each sponsoring organization promotes members to serve as voting delegates within the NCUTCD.

Adoption

Eighteen states have adopted the national MUTCD as is. Twenty-two states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the United States Department of Defense through the Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command (SDDC) have all adopted supplements to the MUTCD. Ten states have adopted their own editions of the MUTCD "in substantial conformance to" an edition of the national MUTCD, annotated throughout with state-specific modifications and clarifications.[28][29][30][31] The Guam Department of Public Works has also adopted the MUTCD in some form.[32]

The following state-specific MUTCD editions are currently in effect:

- California Department of Transportation: California Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (CA MUTCD)

- Delaware Department of Transportation: Delaware Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (DE MUTCD)

- Indiana Department of Transportation: Indiana Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (IMUTCD)

- Maryland State Highway Administration: Maryland Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MdMUTCD)

- Michigan Department of Transportation: Michigan Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MMUTCD)

- Minnesota Department of Transportation: Minnesota Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MN MUTCD)

- Missouri Department of Transportation: Engineering Policy Guide (EPG), section 900

- Ohio Department of Transportation: Ohio Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices (OMUTCD)

- Texas Department of Transportation: Texas Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (TMUTCD)

- Utah Department of Transportation: Utah Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (Utah MUTCD)

Other jurisdictions

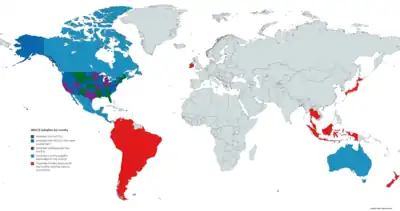

The United States is among the majority of countries around the world that have not ratified the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals (based primarily on European signage traditions), and the FHWA MUTCD differs significantly from the Vienna Convention. Apart from the 1971 effort to adopt several Vienna Convention-inspired symbol signs (as explained above), achieving worldwide uniformity in traffic control devices was never a priority for AASHTO because the number of motorists driving regularly on multiple continents was relatively small during the 20th century.[1]

Warning signs (alerting drivers of unexpected or hazardous conditions) tend to be more verbose than their Vienna Convention counterparts.[1] On the other hand, MUTCD guide signs (directing or informing road users of their location or of destinations) tend to be less verbose, since they are optimized for reading at high speeds on freeways and expressways.[1]

The MUTCD lacks a mandatory sign group like the Vienna Convention does, a separate category for those signs like "Right Turn Only" and "Keep Right" that tell traffic what it must do instead of what it must not do. Instead, the MUTCD primarily classifies them with the other regulatory signs that inform drivers of traffic regulations.

The MUTCD has become widely influential outside the United States; for example, the use of yellow stripes to divide opposing traffic has been widely adopted throughout the Western Hemisphere. Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and some Asian countries use many road signs influenced by the MUTCD.

Canada

For road signs in Canada, the Transportation Association of Canada (TAC) publishes its own Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Canada for use by Canadian jurisdictions.[35] Although it serves a similar role to the FHWA MUTCD, it has been independently developed and has a number of key differences with its US counterpart, most notably the inclusion of bilingual (English/French) signage for jurisdictions such as New Brunswick and Ontario with significant anglophone and francophone population, a heavier reliance on symbols rather than text legends and metric measurements instead of imperial.

The Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (MTO) also has historically used its own MUTCD which bore many similarities to the TAC MUTCDC. However, as of approximately 2000, MTO has been developing the Ontario Traffic Manual (OTM), a series of smaller volumes each covering different aspects of traffic control (e.g., regulatory signs, warning signs, sign design principles, traffic signals, etc.).

Central America

For road signs in Central American countries, the Central American Integration System (SICA) publishes its own Manual Centroamericano de Dispositivos Uniformes para el Control del Transito, a Central American equivalent to the US MUTCD.

See also

References

- Johnson, A.E. (1965). Johnson, A.E. (ed.). "A Story of Road Signing". American Association of State Highway Officials: A Story of the Beginning, Purposes, Growth, Activities, and Achievements of AASHO. Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway Officials. pp. 129–138.

- Hawkins, H. Gene; Parham, Angelia H.; Womack, Katie N. (2002). "Appendix A: Evolution of U.S. Pavement Marking System". NCHRP Report 484: Feasibility Study for an All-White Pavement Marking System (PDF). Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. pp. A-1–A-7. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Waters, Charles R.; Treble, Gilbert W. (July 1951). "Tests of Highway Signs for United Nations". Traffic Engineering. p. 338.

- "Ohioans tell Europe to keep its signs". Mansfield News Journal. United Press. March 27, 1951. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- Barnett, David (August 21, 1951). "Foreign Highway Signs Catch Eye". The Richmond News Leader. Richmond, Virginia. p. 1-B – via Newspapers.com.

- "U.N. Highway Signs Get Test". Minneapolis Star. March 27, 1951. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- "U.N. Tests New Road Signs in U.S." Air Bulletin: World Affairs. United States Information Service. 1951. pp. 4–5 – via Google Books.

- "Foreign Road Sign Test Arouses Some Criticism". The Independent. Massillon, Ohio. Associated Press. March 27, 1951. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Road Sign Test for UN Given Up". Daily Press. Newport News, Virginia. Associated Press. March 30, 1951. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hoffman, Michael L. (September 23, 1951). "U.N. Nearer Accord on Traffic Signs: Standard Markers of U.S. May Serve as a Basis For World System". The New York Times. p. 125. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- Fisher, Edward C. (1961). Vehicle Traffic Law (1967 supp. ed.). Evanston, Illinois: Traffic Institute, Northwestern University. p. 11.

- American Association of State Highway Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (1971). "Section 3B-1, Center Lines". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 181. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- American Association of State Highway Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (1971). "Section 2D-3, Color, Reflectorization, and Illumination". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 84. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- "Symbols to Replace Words on U.S. Traffic Signs". The New York Times. May 31, 1970. p. 58.

- American Association of State Highway Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (1971). "Section 2A-13, Symbols". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 16. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- Lindsey, Robert (April 23, 1972). "Signs of Progress: Road Symbols Guiding Traffic". The New York Times. p. S22. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- "Robert Conner, Ex-FHA Official, Dies of Cancer". The Washington Post. December 1, 1984.

- Hebert, Ray (January 30, 1972). "New Traffic Signs Bloom as California Goes International". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Available via ProQuest.

- Conniff, James C.G. (March 30, 1975). "Danger: Signs Ahead". The New York Times. p. 183. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Hazlett, Bill (March 23, 1972). "Some Confusing: Wordless Traffic Signs Popping Up". Los Angeles Times. p. E1.

- American Association of State Highway Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (1978). "Section 2A-13, Symbols". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 2A-6.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (2003). "Introduction". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- "Public Comments on new MUTCD". Regulations.gov. docket FHWA-2007-28977.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; National Joint Committee on Traffic Control Devices (2012). "Change List for Revision Numbers 1 and 2, Dated May 2012, to the 2009 Edition of the MUTCD". Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- "National Standards for Traffic Control Devices; the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways; Revision". Federal Register. December 14, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- "Status of Rulemaking for the Eleventh Edition of the MUTCD". Federal Highway Administration. March 2, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways: What's New". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- "MUTCDs & Traffic Control Devices Information by State". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. Federal Highway Administration. July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- Manual de Rotulación para las Vías Públicas en Puerto Rico (PDF) (in Spanish). San Juan, Puerto Rico: Puerto Rico Highways and Transportation Authority. 2020.

- Department of Defense Supplement to the National Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (PDF). Scott Air Force Base, Illinois: Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command. 2015.

- "MUTCD". Scott Air Force Base, Illinois: Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command Transportation Engineering Agency. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- "List of Approved Requests for Interim Approval". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. Federal Highway Administration. May 15, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- "Figure 2B-3. Speed Limit and Photo Enforcement Signs and Plaques". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals (PDF) (2006 consolidated ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. pp. 41, 91. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- "Transportation Association of Canada". Transportation Association of Canada. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

External links

- Official website

- National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD) website

- MUTCD History by H. Gene Hawkins